The Theory and Practice of the American Proletarian Novel, Based Upon Four Selected Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Steinbeck As a Radical Novelist Shawn Jasinski University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2008 John Steinbeck As a Radical Novelist Shawn Jasinski University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Recommended Citation Jasinski, Shawn, "John Steinbeck As a Radical Novelist" (2008). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 117. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/117 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN STEINBECK AS A RADICAL NOVELIST A Thesis Presented by Shawn Mark Jasinski to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in English May, 2008 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts specializing in English. Thesis Examination Committee: Advisor - John ~yhnari,lP$. D +A d)d Chairperson Patrick Neal, Ph. D. /'----I Vice President for Research and Dean of Graduate Studies Date: April 4", 2008 ABSTRACT The radical literary tradition of the 1930‟s inspired many American authors to become more concerned with the struggle of the proletariat. John Steinbeck is one of these authors. Steinbeck‟s novels throughout the 1930‟s and 1940‟s display a lack of agreement with the common Communist principles being portrayed by other radical novelists, but also a definite alignment with several more basic Marxist principles. -

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan the RADICAL CRITICISM OP GRANVILLE HICKS in the 1 9 3 0 *S

72 - 15,245 LONG, Terry Lester, 1936- THE RADICAL CRITICISM OF GRANVILLE HICKS IN THE 1930’S. The Ohio State University in Cooperation with Miami (Ohio) University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THE RADICAL CRITICISM OP GRANVILLE HICKS IN THE 1 9 3 0 *S DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Terry L. Long, B. A. , M. A. Ohe Ohio State University 1971 Approved by A d v iser Department of English PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Hicks and the 1930*s ....................................... 1 II. Granville Hicks: Liberal, 1927-1932 .... 31 III. Granville Hicks: Marxist, 1932-1939 .... 66 IV. Hicks on the Marxian Method................... 121 V. Hicks as a Marxian A nalyst ........................ 157 V I. The B reak With Communism and A f t e r ..... 233 VII. Hicks and Marxist Criticism in Perspective . 258 BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................... 279 i i CHAPTER I HICKS AM5 THE 1930* s The world was aflame with troubles In the 1930fs. They were years of economic crisis, war, and political upheaval. America, as Tennessee Williams said, "... was matriculating in a school for the blind." They were years of bewilderment and frustration for the common man. For many American writers and thinkers, the events of the decade called for several changes from the twenties; a move to the political left, a concern for the misery of the masses, sympathy for the labor movement, support of the Communist Party, hope for Russia as a symbol of the future, fear and hatred of fascism. -

Thackeray's Satire on British Society of the Early Victorian Era Through

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI i MATERIALISM AND SOCIAL STATUS: THACKERAY’S SATIRE ON BRITISH SOCIETY OF THE EARLY VICTORIAN ERA THROUGH REBECCA SHARP CHARACTER IN VANITY FAIR AThesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By Nadia Octaviani Student Number: 021214111 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2008 i i PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI vi We are what we imagine Our very existence consist in our imagination of ourselves Our best destiny is to imagine who and what we are The greatest tragedy to befall us is to go unimagined N. Scott Nomaday This thesis is dedicated to my family, to my friends, and to my self. vi vi PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have given me their affection, support, guidance and criticism in finishing every part of my thesis. First of all, I would like to bestow my gratitude to Allah s.w.t. for guiding and keeping me not to stray from His path and finally finish my thesis. My deepest gratitude is given to my beloved dad and mom, Pak Kun and Mama Ning, who have given me their never-ending affection and prayer to support me through the life. I also thank them for keeping asking patiently on the progress of my thesis. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Upton Sinclair Against Capitalism

Scientific Journal in Humanities, 1(1):41-46,2012 ISSN:2298-0245 Walking Through The Jungle: Upton Sinclair Against Capitalism George SHADURI* Abstract At the beginning of the 20th century, the American novel started exploring social themes and raising social problems. Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle, which appeared in 1906, was a true sensation for American reading community. On the one hand, it described the outra- geous practices of meatpacking industry prevalent at those times on the example of slaughterhouses in Chicago suburbs; on the other hand, it exposed the hapless life of American worker: the book showed what kind of suffering the worker experienced from his thankless work and poor living conditions. Sinclair hoped that the novel, which was avidly read both in America and abroad, would help improve the plight of American worker. However, to his disappointment, the government and society focused their attention exclusively on unhealthy meatpacking practices, which brought about necessary, but still superficial reforms, ignoring the main topic: the life of the common worker. Sinclair was labeled “a muckraker”, whereas he in reality aspired for the higher ideal of changing the existing social order, the thought expressed both in his novels and articles. The writer did not take into account that his ideas of non-violent, but drastic change of social order were alien for American society, for which capitalism was the most natural and acceptable form of functioning. The present article refers to the opinions of both American and non-American scholars to explain the reasons for the failure of Sinclair’s expectations, and, based on their views, concludes why such a failure took place. -

The Representation of the First World War in the American Novel

The representation of the first world war in the American novel Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Doehler, James Harold, 1910- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 07:22:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553556 THE REPRESENTATION OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN THE AMERICAN NOVEL ■ . ■ v ' James Harold Doehler A Thesis aotsdited to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Co U e g e University of Arisom 1941 Director of Thesis e & a i m c > m J::-! - . V 3^ J , UF' Z" , r. •. TwiLgr-t. ' : fejCtm^L «••»«[?; ^ aJbtadE >1 *il *iv v I ; t. .•>#»>^ ii«;' .:r i»: s a * 3LXV>.Zj.. , 4 W i > l iie* L V W ?! df{t t*- * ? [ /?// TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ..... .......... < 1 II. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE WAR. 9 III. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE 1920*8 . 32 IV. DOS PASSOS, HEMINGWAY, AND CUMMINGS 60 V. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE 1930*8 . 85 VI. CONCLUSION ....................... 103 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................... 106 l a y 4 7 7 CHAPIER I niiRODUcnoa The purpose of this work is to discover the attitudes toward the first World War which were revealed in the American novel from 1914 to 1941. -

Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past

The Green Fields of the Mind: Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past Blaine Quincy Waide A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Folklore Program, Department of American Studies Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: William Ferris Robert Cantwell Timothy Marr ©2009 Blaine Quincy Waide ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Blaine Quincy Waide: The Green Fields of the Mind: Robert Johnson, Folk Revivalism, and Disremembering the American Past (Under the direction of William Ferris) This thesis seeks to understand the phenomenon of folk revivalism as it occurred in America during several moments in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. More specifically, I examine how and why often marginalized southern vernacular musicians, especially Mississippi blues singer Robert Johnson, were celebrated during the folk revivals of the 1930s and 1960s as possessing something inherently American, and differentiate these periods of intense interest in the traditional music of the American South from the most recent example of revivalism early in the new millennium. In the process, I suggest the term “disremembering” to elucidate the ways in which the intent of some vernacular traditions, such as blues music, has often been redirected towards a different social or political purpose when communities with divergent needs in a stratified society have convened around a common interest in cultural practice. iii Table of Contents Chapter Introduction: Imagining America in an Iowa Cornfield and at a Mississippi Crossroads…………………………………………………………………………1 I. Discovering America in the Mouth of Jim Crow: Alan Lomax, Robert Johnson, and the Mississippi Paradox…………………………………...23 II. -

Troubled Masculinity at Midlife: a Study of Dickens's Hard Times

235 Troubled Masculinity at Midlife: A Study of Dickens’s Hard Times HATADA Mio Hard Timesで提示される “Fact”と“Fancy”の2つの対照的な世界、あるいは価値観は、一見 すると相反するもののように思われるが、この小説は両者の対立よりもむしろ、両者がいかに 密接な関係を持っているかを暗示しているように思われる。そして、主要な登場人物は複雑に 絡まり合ったこれら2つの世界に、それぞれのやり方で関わりを持ち、反応を示す。興味深い ことに、2つの絡み合う世界は、主要な人物(その多くは中年の男性である)の抱えている問 題とも密接な関係を持っている。本稿ではHard Timesにおける2つの世界を、作品中で直接姿 を現すことのないSissy の父親の存在を手がかりに、中年期の男性が経験するmasculinityの危 機、という観点から再考している。 キーワード:aging, masculinity, gender Introduction It is well known that F. R. Leavis included Hard Times in his work The Great Tradition, calling it “a completely serious work of art” (Leavis 258) with the “subtlety of achieved art” (Leavis 279). Much earlier, John Ruskin estimated the novel as “the greatest” of Dickens’s novels, and asserted that it “should be studied with close and earnest care by persons interested in social questions” (34). Many other critics make much of the aspect of Hard Times as a critique of the contemporary society, and it has often been treated with other industrial novels such as Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (1855). Humphry House, for instance, points out that Dickens was “thinking much more about social problems,” and that “Hard Times is one of Dickens’s most thought-about books.” He goes on to assert that “in the ’fi fties, his novels begin to show a greater complication of plot than before” because “ he was intending to use them as a vehicle of more concentrated sociological argument” (House 205). David Lodge, too, affi rms, “Hard Times manifests its identity as a polemical work, a critique of mid-Victorian industrial society dominated by materialism, acquisitiveness and ruthlessly competitive capitalist economics,” which are “represented... by the Utilitarians” (Lodge 69‒70). -

The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2001 The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction Walter Edwin Squire University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Squire, Walter Edwin, "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6439 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Edwin Squire entitled "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Squire entitled "The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

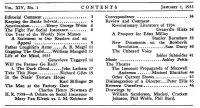

Vol. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial

VoL. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial Comment • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. ..• 3 Correspondence • . • • . • • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • 34 Keeping the Banks Solvent.............. 6 Review and Comment Americanism .•.••••. Henry George Weiss 6 Revolutionary Literature of 1934 The Fight For Social Insurance. • • • . • • • • 8 Granville Hicks 36 One Year of the Weekly New Masses A Prospect for Edna Millay A Statement to Our Readers and an · Stanley Burnshaw 39 Appeal • • ••••• ••••••. .• • • • . • • ••• 9 New Documents on the Bolshevik Father Coughlin's Army .••.. A. B. Magi! 11 Revolution ...•..••.•.•• Sam Darcy 40 Gagging The Guild •••• William Mangold 15 The Unheard Voice Life of the Mind, 1935 Isidor Schneider 41 Genevieve Taggard 16 Music .................... Ashley Pettis Will the Farmer Go Red? The Theatre 5. The Dark Cloud ...... John Latham 17 The Innocent Propaganda of Maxwell Take This Hope .......•... Richard Giles 19 Anderson ••....• Michael Blankfort 44 In the Nazis' Torture House Other Current Shows .•.••••.••••..•• 45 Karl Billinger 20 Disintegration of a Director ••. Peter Ellis 45 The Man at the Factory Gate Between Ourselves • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • . 46 Charles Henry Newman 27 Drawings by H. R. 7598-A Debate on Social Insurance William Sanderson, Mackey, Crockett Mary Van Kleeck ,ys. I. M. Rubinow 28 Johnson, Phil Wolfe, Phil Bard. VoL. XIV, No. 2 CONTENTS JANUARY 8, 1935 Editorial Comment . • . • . • • . 3 Arming the Masses .••.••••. Ben Field 25 Betrayal by the N.A.A.C.P. •. • . • 6 American Decadence Mapped Terror in "Liberal" Wisconsin........... 8 .Samuel Levenson 25 The Truth About the Crawford Case Fire on the Andes •••... Frank Gordon 26 Martha Gruening 9 Brief Review ••••••••••••••• , • • • . • • 27 Moscow Street. ....... Charles B. Strauss 15 Book Notes •••••••••••••••.••.•••••• 27 The Auto Workers Face 1935 Art A. -

Working-Class Representation As a Literary and Political Practice from the General Strike to the Winter of Discontent

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Representing revolt: working-class representation as a literary and political practice from the General Strike to the Winter of Discontent Matti Ron PhD English Literature University of East Anglia School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing August 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Though the dual sense of representation—as an issue of both aesthetic or organisational forms—has long been noted within Marxist literary criticism and political theory, these differing uses of the term have generally been considered to be little more than semantically related. This thesis, then, seeks to address this gap in the discourse by looking at working- class representation as both a literary and political practice to show that their relationship is not just one of being merely similar or analogous, but rather that they are structurally homologous. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will perform close readings of clusters of texts to chart the development of working-class fiction between two high-points of class struggle in Britain—the 1926 General Strike and the 1978-79 Winter of Discontent—with the intention -

Vita for Alan M. Wald

1 July 2016 VITA FOR ALAN M. WALD Emeritus Faculty as of June 2014 FORMERLY H. CHANDLER DAVIS COLLEGIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND AMERICAN CULTURE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR Address Office: Prof. Alan Wald, English Department, University of Michigan, 3187 Angell Hall, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48109-1003. Home: 3633 Bradford Square Drive, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48103 Faxes can be received at 734-763-3128. E-mail: [email protected] Education B.A. Antioch College, 1969 (Literature) M.A. University of California at Berkeley, 1971 (English) Ph. D. University of California at Berkeley, 1974 (English) Occupational History Lecturer in English, San Jose State University, Fall 1974 Associate in English, University of California at Berkeley, Spring 1975 Assistant Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1975-81 Associate Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1981-86 Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1986- Director, Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, 2000-2003 H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor, University of Michigan, 2007-2014 Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan, 2014- Research and Teaching Specialties 20th Century United States Literature Realism, Naturalism, Modernism in Mid-20th Century U.S. Literature Literary Radicalism in the United States Marxism and U.S. Cultural Studies African American Writers on the Left Modernist Poetry and the Left The Thirties New York Jewish Writers and Intellectuals Twentieth Century History of Socialist, Communist, Trotskyist and New Left Movements in the U.S.