Proletarian Literature, a N Unidentified Literary Object

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms, a XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan the RADICAL CRITICISM OP GRANVILLE HICKS in the 1 9 3 0 *S

72 - 15,245 LONG, Terry Lester, 1936- THE RADICAL CRITICISM OF GRANVILLE HICKS IN THE 1930’S. The Ohio State University in Cooperation with Miami (Ohio) University, Ph.D., 1971 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THE RADICAL CRITICISM OP GRANVILLE HICKS IN THE 1 9 3 0 *S DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Terry L. Long, B. A. , M. A. Ohe Ohio State University 1971 Approved by A d v iser Department of English PLEASE NOTE: Some pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. Hicks and the 1930*s ....................................... 1 II. Granville Hicks: Liberal, 1927-1932 .... 31 III. Granville Hicks: Marxist, 1932-1939 .... 66 IV. Hicks on the Marxian Method................... 121 V. Hicks as a Marxian A nalyst ........................ 157 V I. The B reak With Communism and A f t e r ..... 233 VII. Hicks and Marxist Criticism in Perspective . 258 BIBLIOGRAPHY......................................................................................... 279 i i CHAPTER I HICKS AM5 THE 1930* s The world was aflame with troubles In the 1930fs. They were years of economic crisis, war, and political upheaval. America, as Tennessee Williams said, "... was matriculating in a school for the blind." They were years of bewilderment and frustration for the common man. For many American writers and thinkers, the events of the decade called for several changes from the twenties; a move to the political left, a concern for the misery of the masses, sympathy for the labor movement, support of the Communist Party, hope for Russia as a symbol of the future, fear and hatred of fascism. -

Changing Attitudes Toward Charity: the Values of Depression-Era America As Reflected in Its Literature

CHANGING ATTITUDES TOWARD CHARITY: THE VALUES OF DEPRESSION-ERA AMERICA AS REFLECTED IN ITS LITERATURE By Steven M. Stary As a time of economic and political crisis, the Great Depression influenced authors who VRXJKWWRUHZULWH$PHULFD¶VXQGHUO\LQJmythology of rugged individualism into one of cooperative or communal sensibility. Through their creative use of narrative technique, the authors examined in this thesis bring their readers into close identification with the characters and events they describe. Creating connection between middle-class readers and the destitute subjects of their works, the authors promoted personal and communal solutions to the effects of the Depression rather than the impersonal and demeaning forms of charity doled out by lRFDOJRYHUQPHQWVDQGSULYDWHFKDULWLHV0HULGHO/H6XHXU¶V DUWLFOHV³:RPHQRQWKH%UHDGOLQHV´³:RPHQDUH+XQJU\´DQG³,:DV0DUFKLQJ´ DORQJZLWK7RP.URPHU¶VQRYHOWaiting for Nothing, are examined for their narrative technique as well as depictions of American attitudes toward charitable giving and toward those who receive charity. The works of Le Sueur and Kromer are shown as a SURJUHVVLRQFXOPLQDWLQJLQ-RKQ6WHLQEHFN¶VThe Grapes of Wrath later in the decade. By the end of the 1930s significant progress had been made in changing American values toward communal sensibility through the work of these authors and the economic programs of the New Deal, but the shift in attitude would not be completely accomplished or enduring. To my wife, Dierdra, who made it possible for me to keep on writing, even though it took longer than I thought it would. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Dr. Don Dingledine, my thesis advisor, who has helped to see this work to completion. It is due to his guidance this project has its good points, and entirely my fault where it does not. -

Limited Editions Club

g g OAK KNOLL BOOKS www.oakknoll.com 310 Delaware Street, New Castle, DE 19720 Oak Knoll Books was founded in 1976 by Bob Fleck, a chemical engineer by training, who let his hobby get the best of him. Somehow, making oil refineries more efficient using mathematics and computers paled in comparison to the joy of handling books. Oak Knoll Press, the second part of the business, was established in 1978 as a logical extension of Oak Knoll Books. Today, Oak Knoll Books is a thriving company that maintains an inventory of about 25,000 titles. Our main specialties continue to be books about bibliography, book collecting, book design, book illustration, book selling, bookbinding, bookplates, children’s books, Delaware books, fine press books, forgery, graphic arts, libraries, literary criticism, marbling, papermaking, printing history, publishing, typography & type specimens, and writing & calligraphy — plus books about the history of all of these fields. Oak Knoll Books is a member of the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB — about 2,000 dealers in 22 countries) and the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA — over 450 dealers in the US). Their logos appear on all of our antiquarian catalogues and web pages. These logos mean that we guarantee accurate descriptions and customer satisfaction. Our founder, Bob Fleck, has long been a proponent of the ethical principles embodied by ILAB & the ABAA. He has taken a leadership role in both organizations and is a past president of both the ABAA and ILAB. We are located in the historic colonial town of New Castle (founded 1651), next to the Delaware River and have an open shop for visitors. -

Sentimental Appropriations: Contemporary Sympathy In

SENTIMENTAL APPROPRIATIONS: CONTEMPORARY SYMPATHY IN THE NOVELS OF GRACE LUMPKIN, JOSEPHINE JOHNSON, JOHN STEINBECK, MARGARET WALKER, OCTAVIA BUTLER, AND TONI MORRISON Jennifer A. Williamson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Linda Wagner-Martin William L. Andrews Philip Gura Fred Hobson Wahneema Lubiano © 2011 Jennifer A. Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JENNIFER A. WILLIAMSON: Sentimental Appropriations: Contemporary Sympathy in the Novels of Grace Lumpkin, Josephine Johnson, John Steinbeck, Margaret Walker, Octavia Butler, and Toni Morrison (Under the direction of Linda Wagner-Martin) This project investigates the appearance of the nineteenth-century American sentimental mode in more recent literature, revealing that the cultural work of sentimentalism continues in the twentieth-century and beyond. By examining working-class literature that adopts the rhetoric of “feeling right” in order to promote a proletarian ideology as well as neo-slave narratives that wrestle with the legacy of slavery, this study explores the ways contemporary authors engage with familiar sentimental tropes and ideals. Despite modernism’s influential assertion that sentimentalism portrays emotion that lacks reality or depth, narrative claims to feeling— particularly those based in common and recognizable forms of suffering—remain popular. It seems clear that such authors as Grace Lumpkin, Josephine Johnson, John Steinbeck, Margaret Walker, Octavia Butler, and Toni Morrison apply the rhetorical methods of sentimentalism to the cultural struggles of their age. Contemporary authors self-consciously struggle with sentimentalism’s gender, class, and race ideals; however, sentimentalism’s dual ability to promote these ideals and extend identification across them makes it an attractive and effective mode for political and social influence. -

The Representation of the First World War in the American Novel

The representation of the first world war in the American novel Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Doehler, James Harold, 1910- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 07:22:59 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553556 THE REPRESENTATION OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR IN THE AMERICAN NOVEL ■ . ■ v ' James Harold Doehler A Thesis aotsdited to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Co U e g e University of Arisom 1941 Director of Thesis e & a i m c > m J::-! - . V 3^ J , UF' Z" , r. •. TwiLgr-t. ' : fejCtm^L «••»«[?; ^ aJbtadE >1 *il *iv v I ; t. .•>#»>^ ii«;' .:r i»: s a * 3LXV>.Zj.. , 4 W i > l iie* L V W ?! df{t t*- * ? [ /?// TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ..... .......... < 1 II. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE WAR. 9 III. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE 1920*8 . 32 IV. DOS PASSOS, HEMINGWAY, AND CUMMINGS 60 V. NOVELS WRITTEN DURING THE 1930*8 . 85 VI. CONCLUSION ....................... 103 BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................... 106 l a y 4 7 7 CHAPIER I niiRODUcnoa The purpose of this work is to discover the attitudes toward the first World War which were revealed in the American novel from 1914 to 1941. -

Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood

LH 19_1 FInal.qxp_Left History 19.1.qxd 2015-08-28 4:01 PM Page 57 Michael Gold & Dalton Trumbo on Spartacus, Blacklist Hollywood, Howard Fast, and the Demise of American Communism 1 Henry I. MacAdam, DeVry University Howard Fast is in town, helping them carpenter a six-million dollar production of his Spartacus . It is to be one of those super-duper Cecil deMille epics, all swollen up with cos - tumes and the genuine furniture, with the slave revolution far in the background and a love tri - angle bigger than the Empire State Building huge in the foreground . Michael Gold, 30 May 1959 —— Mike Gold has made savage comments about a book he clearly knows nothing about. Then he has announced, in advance of seeing it, precisely what sort of film will be made from the book. He knows nothing about the book, nothing about the film, nothing about the screenplay or who wrote it, nothing about [how] the book was purchased . Dalton Trumbo, 2 June 1959 Introduction Of the three tumultuous years (1958-1960) needed to transform Howard Fast’s novel Spartacus into the film of the same name, 1959 was the most problematic. From the start of production in late January until the end of all but re-shoots by late December, the project itself, the careers of its creators and financiers, and the studio that sponsored it were in jeopardy a half-dozen times. Blacklist Hollywood was a scary place to make a film based on a self-published novel by a “Commie author” (Fast), and a script by a “Commie screenwriter” (Trumbo). -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2001 The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction Walter Edwin Squire University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Squire, Walter Edwin, "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6439 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Edwin Squire entitled "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Squire entitled "The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920S-1940S' Kathleen A

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920s-1940s' Kathleen A. Brown and Elizabeth Faue William Armistead Nelson Collier, a sometime anarchist and poet, self- professed free lover and political revolutionary, inhabited a world on the "lunatic fringe" of the American Left. Between the years 1908 and 1948, he traversed the legitimate and illegitimate boundaries of American radicalism. After escaping commitment to an asylum, Collier lived in several cooperative colonies - Upton Sinclair's Helicon Hall, the Single Tax Colony in Fairhope, Alabama, and April Farm in Pennsylvania. He married (three times legally) andor had sexual relationships with a number of radical women, and traveled the United States and Europe as the Johnny Appleseed of Non-Monogamy. After years of dabbling in anarchism and communism, Collier came to understand himself as a radical individualist. He sought social justice for the proletariat more in the realm of spiritual and sexual life than in material struggle.* Bearded, crude, abrupt and fractious, Collier was hardly the model of twentieth century American radicalism. His lover, Francoise Delisle, later wrote of him, "The most smarting discovery .. was that he was only a dilettante, who remained on the outskirts of the left wing movement, an idler and loafer, flirting with it, in search of amorous affairs, and contributing nothing of value, not even a hard day's work."3 Most historians of the 20th century Left would share Delisle's disdain. Seeking to change society by changing the intimate relations on which it was built, Collier was a compatriot, they would argue, not of William Z. -

Eyewitness to Missing Moments: the Foreign Reporting of Josephine Herbst

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 295 217 CS 211 320 AUTHOR Cassara, Catherine TITLE Eyewitness to Missing Moments: The Foreign Reporting of Josephine Herbst. PUB DATE Jul 88 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (711;t7 P,)rtland, OR, July 2-5, 1988). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Historical Materials (060) Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Discourse Analysis; Foreign Countries; Journalism; *Modern History; *News Reporting; Political Attitudes; Political Influences; United States History; Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS Cuba; Germany; *Herbst (Josephine); Journalism History; *Women Journalists; Writing Style ABSTRACT Concentrating on her domestic and foreign news stories of the 1930s, a study analyzed the news reporting of American novelist Josephine Herbst. Although the study focused on Herbst's reporting from Cuba and Germany, other writings were examined, including several fictional pieces, memoirs, and literary criticism. Herbst's work was analyzed according to several criteria. Each piece was reviewed for its stylistic characteristics--language usage, narrative form, source use and balance, and readability. Background material on the thirties provides context not only for Herbst's politics, experiences, and social views, but also for her writing -style and genre choices. Analysis revealed that Herbst's choice of topics was motivated by her Marxist politics. Analysis also showed that Herbst's writing has been overlooked in j,..urnalism history, and although her sex and politics may be enough to generate renewed interest in her, the justification for consideration of her work rests on its ability to capture a sense of time and people otherwise lost in "missing moments" of history. -

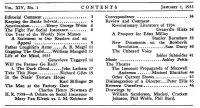

Vol. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial

VoL. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial Comment • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. ..• 3 Correspondence • . • • . • • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • 34 Keeping the Banks Solvent.............. 6 Review and Comment Americanism .•.••••. Henry George Weiss 6 Revolutionary Literature of 1934 The Fight For Social Insurance. • • • . • • • • 8 Granville Hicks 36 One Year of the Weekly New Masses A Prospect for Edna Millay A Statement to Our Readers and an · Stanley Burnshaw 39 Appeal • • ••••• ••••••. .• • • • . • • ••• 9 New Documents on the Bolshevik Father Coughlin's Army .••.. A. B. Magi! 11 Revolution ...•..••.•.•• Sam Darcy 40 Gagging The Guild •••• William Mangold 15 The Unheard Voice Life of the Mind, 1935 Isidor Schneider 41 Genevieve Taggard 16 Music .................... Ashley Pettis Will the Farmer Go Red? The Theatre 5. The Dark Cloud ...... John Latham 17 The Innocent Propaganda of Maxwell Take This Hope .......•... Richard Giles 19 Anderson ••....• Michael Blankfort 44 In the Nazis' Torture House Other Current Shows .•.••••.••••..•• 45 Karl Billinger 20 Disintegration of a Director ••. Peter Ellis 45 The Man at the Factory Gate Between Ourselves • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • . 46 Charles Henry Newman 27 Drawings by H. R. 7598-A Debate on Social Insurance William Sanderson, Mackey, Crockett Mary Van Kleeck ,ys. I. M. Rubinow 28 Johnson, Phil Wolfe, Phil Bard. VoL. XIV, No. 2 CONTENTS JANUARY 8, 1935 Editorial Comment . • . • . • • . 3 Arming the Masses .••.••••. Ben Field 25 Betrayal by the N.A.A.C.P. •. • . • 6 American Decadence Mapped Terror in "Liberal" Wisconsin........... 8 .Samuel Levenson 25 The Truth About the Crawford Case Fire on the Andes •••... Frank Gordon 26 Martha Gruening 9 Brief Review ••••••••••••••• , • • • . • • 27 Moscow Street. ....... Charles B. Strauss 15 Book Notes •••••••••••••••.••.•••••• 27 The Auto Workers Face 1935 Art A. -

Working-Class Representation As a Literary and Political Practice from the General Strike to the Winter of Discontent

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of East Anglia digital repository Representing revolt: working-class representation as a literary and political practice from the General Strike to the Winter of Discontent Matti Ron PhD English Literature University of East Anglia School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing August 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. Abstract Though the dual sense of representation—as an issue of both aesthetic or organisational forms—has long been noted within Marxist literary criticism and political theory, these differing uses of the term have generally been considered to be little more than semantically related. This thesis, then, seeks to address this gap in the discourse by looking at working- class representation as both a literary and political practice to show that their relationship is not just one of being merely similar or analogous, but rather that they are structurally homologous. To demonstrate this point, this thesis will perform close readings of clusters of texts to chart the development of working-class fiction between two high-points of class struggle in Britain—the 1926 General Strike and the 1978-79 Winter of Discontent—with the intention