Eyewitness to Missing Moments: the Foreign Reporting of Josephine Herbst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sentimental Appropriations: Contemporary Sympathy In

SENTIMENTAL APPROPRIATIONS: CONTEMPORARY SYMPATHY IN THE NOVELS OF GRACE LUMPKIN, JOSEPHINE JOHNSON, JOHN STEINBECK, MARGARET WALKER, OCTAVIA BUTLER, AND TONI MORRISON Jennifer A. Williamson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by: Linda Wagner-Martin William L. Andrews Philip Gura Fred Hobson Wahneema Lubiano © 2011 Jennifer A. Williamson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JENNIFER A. WILLIAMSON: Sentimental Appropriations: Contemporary Sympathy in the Novels of Grace Lumpkin, Josephine Johnson, John Steinbeck, Margaret Walker, Octavia Butler, and Toni Morrison (Under the direction of Linda Wagner-Martin) This project investigates the appearance of the nineteenth-century American sentimental mode in more recent literature, revealing that the cultural work of sentimentalism continues in the twentieth-century and beyond. By examining working-class literature that adopts the rhetoric of “feeling right” in order to promote a proletarian ideology as well as neo-slave narratives that wrestle with the legacy of slavery, this study explores the ways contemporary authors engage with familiar sentimental tropes and ideals. Despite modernism’s influential assertion that sentimentalism portrays emotion that lacks reality or depth, narrative claims to feeling— particularly those based in common and recognizable forms of suffering—remain popular. It seems clear that such authors as Grace Lumpkin, Josephine Johnson, John Steinbeck, Margaret Walker, Octavia Butler, and Toni Morrison apply the rhetorical methods of sentimentalism to the cultural struggles of their age. Contemporary authors self-consciously struggle with sentimentalism’s gender, class, and race ideals; however, sentimentalism’s dual ability to promote these ideals and extend identification across them makes it an attractive and effective mode for political and social influence. -

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920S-1940S' Kathleen A

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920s-1940s' Kathleen A. Brown and Elizabeth Faue William Armistead Nelson Collier, a sometime anarchist and poet, self- professed free lover and political revolutionary, inhabited a world on the "lunatic fringe" of the American Left. Between the years 1908 and 1948, he traversed the legitimate and illegitimate boundaries of American radicalism. After escaping commitment to an asylum, Collier lived in several cooperative colonies - Upton Sinclair's Helicon Hall, the Single Tax Colony in Fairhope, Alabama, and April Farm in Pennsylvania. He married (three times legally) andor had sexual relationships with a number of radical women, and traveled the United States and Europe as the Johnny Appleseed of Non-Monogamy. After years of dabbling in anarchism and communism, Collier came to understand himself as a radical individualist. He sought social justice for the proletariat more in the realm of spiritual and sexual life than in material struggle.* Bearded, crude, abrupt and fractious, Collier was hardly the model of twentieth century American radicalism. His lover, Francoise Delisle, later wrote of him, "The most smarting discovery .. was that he was only a dilettante, who remained on the outskirts of the left wing movement, an idler and loafer, flirting with it, in search of amorous affairs, and contributing nothing of value, not even a hard day's work."3 Most historians of the 20th century Left would share Delisle's disdain. Seeking to change society by changing the intimate relations on which it was built, Collier was a compatriot, they would argue, not of William Z. -

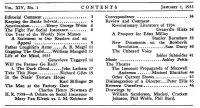

Vol. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial

VoL. XIV, No. 1 CONTENTS JANUARY 1, 1935 Editorial Comment • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • .. ..• 3 Correspondence • . • • . • • . • • . • • • • • • . • . • • 34 Keeping the Banks Solvent.............. 6 Review and Comment Americanism .•.••••. Henry George Weiss 6 Revolutionary Literature of 1934 The Fight For Social Insurance. • • • . • • • • 8 Granville Hicks 36 One Year of the Weekly New Masses A Prospect for Edna Millay A Statement to Our Readers and an · Stanley Burnshaw 39 Appeal • • ••••• ••••••. .• • • • . • • ••• 9 New Documents on the Bolshevik Father Coughlin's Army .••.. A. B. Magi! 11 Revolution ...•..••.•.•• Sam Darcy 40 Gagging The Guild •••• William Mangold 15 The Unheard Voice Life of the Mind, 1935 Isidor Schneider 41 Genevieve Taggard 16 Music .................... Ashley Pettis Will the Farmer Go Red? The Theatre 5. The Dark Cloud ...... John Latham 17 The Innocent Propaganda of Maxwell Take This Hope .......•... Richard Giles 19 Anderson ••....• Michael Blankfort 44 In the Nazis' Torture House Other Current Shows .•.••••.••••..•• 45 Karl Billinger 20 Disintegration of a Director ••. Peter Ellis 45 The Man at the Factory Gate Between Ourselves • • • • • • • • . • • • . • • • • . • • . 46 Charles Henry Newman 27 Drawings by H. R. 7598-A Debate on Social Insurance William Sanderson, Mackey, Crockett Mary Van Kleeck ,ys. I. M. Rubinow 28 Johnson, Phil Wolfe, Phil Bard. VoL. XIV, No. 2 CONTENTS JANUARY 8, 1935 Editorial Comment . • . • . • • . 3 Arming the Masses .••.••••. Ben Field 25 Betrayal by the N.A.A.C.P. •. • . • 6 American Decadence Mapped Terror in "Liberal" Wisconsin........... 8 .Samuel Levenson 25 The Truth About the Crawford Case Fire on the Andes •••... Frank Gordon 26 Martha Gruening 9 Brief Review ••••••••••••••• , • • • . • • 27 Moscow Street. ....... Charles B. Strauss 15 Book Notes •••••••••••••••.••.•••••• 27 The Auto Workers Face 1935 Art A. -

Master Draft “Coolness Under Fire”

“No Job For a Woman:” The Women Who Fought To Report World War II TABLE OF CONTENTS A. SUMMARY This is a request for $625,000 for the Production phase of’ ‘No Job For a Woman’: The Women Who Fought to Report World War II, a one-hour documentary for public television focusing on the story of the women war reporters of World War II, the obstacles they encountered, and their role in contributing to a new way of war reporting. The project received an NEH Consultation Grant in 2002, an NEH Planning Grant in 2004, and an NEH Scripting Grant in 2006. The project has also been selected to be part of the Endowment’s “We the People” initiative because it explores “significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture” and advances “knowledge of the principles that define America.” During the Production phase, we will expand our fundraising campaign to finance the production, projected to cost approximately $735,000. The non-profit sponsor for this film is Women Make Movies. B. SUBJECT AND HUMANITIES THEMES “Bullets don’t discriminate. The dangers are basically the same whether you are male or female,” says NPR’s Iraq war correspondent, Anne Garrels. Today, a woman -- CNN’s Christiane Amanpour -- is possibly the most famous war reporter worldwide. While women reporting war may seem commonplace now, their arrival in the profession is the result of nearly 150 years of struggle and hard work. Many of these battles were fought in the newsrooms and trenches of World War II. During the course of World War II nearly 140 women reporters were accredited to cover events overseas out of a total of approximately 1700 accredited reporters overall. -

Iowa and Some Iowans

Iowa and Some Iowans Fourth Edition, 1996 IOWA AND SOME IOWANS A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries Edited by Betty Jo Buckingham with assistance from Lucille Lettow, Pam Pilcher, and Nancy Haigh o Fourth Edition Iowa Department of Education and the Iowa Educational Media Association 1996 State of Iowa DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Grimes State Office Building Des Moines, Iowa 50319-0146 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Corine A. Hadley, President, Newton C. W. Callison, Burlington, Vice President Susan J. Clouser, Johnston Gregory A. Forristall, Macedonia Sally J. Frudden, Charles City Charlene R. Fulton, Cherokee Gregory D. McClain, Cedar Falls Gene E. Vincent, Carroll ADMINISTRATION Ted Stilwill, Director and Executive Officer of the State Board of Education Dwight R. Carlson, Assistant to Director Gail Sullivan, Chief of Policy and Planning Division of Elementary and Secondary Education Judy Jeffrey, Administrator Debra Van Gorp, Chief, Bureau of Administration, Instruction and School Improvement Lory Nels Johnson, Consultant, English Language Arts/Reading Betty Jo Buckingham, Consultant, Educational Media, Retired Division of Library Services Sharman Smith, Administrator Nancy Haigh It is the policy of the Iowa Department of Education not to discriminate on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability. The Department provides civil rights technical assistance to public school districts, nonpublic schools, area education agencies and community colleges to help them eliminate discrimination in their educational programs, activities, or employment. For assistance, contact the Bureau of School Administration and Accreditation, Iowa Department of Education. Printing funded in part by the Iowa Educational Media Association and by LSCA, Title I. ii PREFACE Developing understanding and appreciation of the history, the natural heritage, the tradition, the literature and the art of Iowa should be one of the goals of school and libraries in the state. -

NEW MASSES Would Like to T Pose a Question at This Moment of Discussion Over the Outcome of the Reich- New Masses Stag Fire Trial: What Do You, Messrs

January 2, 1934 TheGovernor's Committee of Forty- · skies, so that there may be more guns vention ... into a unity congress of the four, appointed to investigate educa- and more battleships. , American student movement." Students tion in New York, reports that "Scien- here and abroad , will await ·with intense tific studies show that increasing the size S we go to press, three important interest the outcome of the W ashington of class registers does not necessarily de- . A student conventions are in session conventions. crease efficiency." Though small classes in Washington. The National Students and the kindergarten rank among the League, after two years of vigorous HE first John Reed Club of Revo- greatest advances in modern education, leadership in campus struggles through- T lutionary Artists and Writers in Dr. Paul .R. Mort, in his report to the out the country, is convened with the this country was organized in New York Governor of New Jersey, also advo- purpose of coordinating its activities to in 1929, just about the time of the great cates increasing the size of classes. Fur- facilitate work among Negro students, crash. Since then about thirty John thermore, he recommends what amounts particularly in the south, and to find Reed Clubs have sprung up in the vari- practically, to wiping out the kinder concrete ways of working in unity with ous sections of the United States. A gartens. The New York committee was · the advanced guard of the working number of these clubs have launched or heavily packed with representative 's of class. The League for Industrial De- are about to launch their own publica- big business, but prominent educators mocracy, reduced by vacillation and op- tions-New Force in Detroit, Leftward .also participated. -

American Berlin Across the Last Century by Joshua Parker

op.asjournal.org http://op.asjournal.org/american-berlin-across-last-century/ American Berlin Across the Last Century by Joshua Parker Over the past century, many studies have been devoted to American literature set in Europe and its capitals. Scholars including D. E. Barclay and E. Glaser-Schmidt, Hans-Jürgen Diller, Hanspeter Dörfel, Elisa Edwards, Peter Freese, Walter Kühnel, Henry Cord Meyer, Martin Meyer, Georg Schmundt-Thomas, and Waldemar Zacharasiewicz have focused on Germany’s image in the American imagination, either literary or from a general standpoint of comparative imagology. Yet despite a marked increase in American fiction treating Berlin since its first designation as Germany’s capital (and an overwhelming increase in the past twenty years), few studies have targeted Berlin itself as a setting or image in American literature and popular consciousness. Those which have are almost limited to Jörg Helbig’s very general collection Welcome to Berlin: Das Image Berlins in der englischprachigen Welt von 1700 bis heute and to Christine Gerhardt’s very specific “‘What was left of Berlin looked bleaker every day’: Berlin, Race, and Ethnicity in Recent American Literature.” This paper surveys trends in the development of American literature set in the German capital from around 1900 to the present. Sections of this paper are adapted from Tales of Berlin in American Literature up to the 21st Century , Leiden: Brill | Rodopi, 2016. Berlin’s place in the American imagination developed later than that of the Rhineland, the Alps or Bavaria. Outlines of America’s fictional Berlin only began to appear clearly in the last warm glow of the nineteenth century, as the city inspired the first American imaginings of a modern, urban German space. -

The Trial of Harry Dexter White: Soviet Agent of Influence

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 12-17-2004 The Trial of Harry Dexter White: Soviet Agent of Influence Tom Adams University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Adams, Tom, "The Trial of Harry Dexter White: Soviet Agent of Influence" (2004). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 177. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/177 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE TRIAL OF HARRY DEXTER WHITE: SOVIET AGENT OF INFLUENCE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Tom A. Adams B.A., Ambassador University, 1975 December 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Late at night, when you are alone with your keyboard, overwhelmed by the mass of information that has to be synthesized, and frozen by writer’s block it is comforting to know you are not entirely on your own. -

Appendix I: a Letter on John Reed's 'The Colorado War'

Appendix I: A Letter on John Reed's 'The Colorado War' Boulder, Colorado. December 5 1915 My dear Mr Sinclair:- I have your letter of Ist inst. I do not think the reporter always got me quite right, or as fully as he might have got me. I did, however, think at the time I testified that Reed's paper in The Metropolitan contained some exaggerations. I did not intend to say that he intentionally told any untruths, and doubtless he had investigated carefully and could produce witnesses to substantiate what he said. Some things are matters of opinion. Some others are almost incapable ofproof. The greater part of Reed's paper is true. But for example, p. 14 1st column July (1914) Metropolitan: 'And orders were that the Ludlow colony must be wiped out. It stood in the way ofMr. Rockefeller's profits.' I believe that a few brutes like Linderfelt probably did intend to wipe this colony out, but that orders were given to this effect by any responsible person either civil or military - is incapable of proof. So the statement that 'only seventeen of them [strikers] had guns', I believe from what Mrs Hollearn [post-mistress] tells me is not quite correct. On p. 16 Reed says the strikers 'eagerly turned over their guns to be delivered to the militia' - Now it is pretty clear from what happened later that many guns were retained: on Dec. 31 st I was at Ludlow when some 50 or so rifles - some new, some old - were found under the tents and there were more - not found. -

Generations, Genealogies, Bildungs in 1930S Novels1

American Uncles and Aunts: Generations, 1 Genealogies, Bildungs in 1930s Novels by Cinzia Scarpino A generation is sometimes a more satisfactory unit for the study of humanity than a lifetime; and spiritual generations are as easy to demark as physical ones. Mary Antin, The Promised Land (1912) This paper stems from a larger research project aimed at considering diverse morphological aspects of a wide corpus of American novels written between 1929 and 1941, such as the intersection of certain chronotopes in particular genres and subgenres, and the reconfiguration of the sociological premises and narrative structure of American Bildungs.2 1 I would like to thank Valeria Gennero and Fiorenzo Iuliano for their patient and careful reading of my drafts; Martino Marazzi for his valuable suggestions on Italian American literature; and Anna Scacchi for giving me directions about L. M. Alcott and Paule Marshall. 2 In defining the corpus of my study I followed two main criteria, one of inclusion (bestsellers and Pulitzers along with proletarian novels, noir and generally acclaimed “canonical” works), and one of exclusion (the absence of an American setting). Since a genre’s unity is defined, in Bakhtinian terms, by its chronotope, the sixty-two-novels corpus has been divided into four main genres: the historical novel; the social novel (a large container for a number of works set in America in the first three decades of the 20th century which can be divided into three main genres: novels of initiation, novels of development, and noir); the proletarian novel (strike and conversion novels, urban-ethnic novels, bottom-dogs novels); the modernist epic (Dos Passos’s U.S.A and parts of Jospehine Herbst’s Trexler Trilogy). -

The Hiss-Chambers Case, 1 W

Western New England Law Review Volume 1 1 (1978-1979) Article 11 Issue 4 1-1-1979 ALLEN WEINSTEIN: PERJURY: THE HISS- CHAMBERS CASE Gordon H. Wentworth Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Gordon H. Wentworth, ALLEN WEINSTEIN: PERJURY: THE HISS-CHAMBERS CASE, 1 W. New Eng. L. Rev. 861 (1979), http://digitalcommons.law.wne.edu/lawreview/vol1/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Review & Student Publications at Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western New England Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Western New England University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERJURY: THE HISS-CHAMBERS CASE: By Allen Weinstein. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1978. Reviewed by Gordon H. Wentworth* The confrontation between Alger Hiss and Whitaker Chambers in 1948 helped to create a political and intellectual divide in the American public which has never been fully bridged. The convic tion of Hiss on two perjury counts officially vindicated Chambers' charges that Hiss had been a secret member of the Communist party actively involved in espionage during the late 1930's. A large part of the liberal establishment, however, refused to accept the conviction and their doubts have been kept alive to this day. The charges were first publicly aired in 1948 when, what Winston Churchill described as the "iron curtain" was clanging shut across Europe. Russian financed spy systems and other illegal activities surfaced in the United States and in Western ,European countries. -

Literary Journalism Studies Te Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies Vol

Literary Journalism Studies Te Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies Vol. 7, No. 1, Spring 2015 ––––––––––––––––– Information for Contributors 4 Note from the Editor 5 ––––––––––––––––– Women and Literary Journalism: A Special Issue 6 On Recognition of Quality Writing by Leonora Flis 7 From Fiction to Fact: Zora Neale Hurston and the Ruby McCollum Trial Roberta S. Maguire 17 Te Life Story of Mrs. Ruby J. McCollum! By Zora Neale Hurston 37 Meridel Le Sueur, Dorothy Day, and the Literary Journalism of Advocacy During the Great Depression by Nancy L. Roberts 45 Te Works of Edna Staebler: Using Literary Journalism to Celebrate the Lives of Ordinary Canadians by Bruce Gillespie 59 Rebels with a Cause: Women Reporting the Spanish Civil War by Isabelle Meuret 79 Preferring “Dirty” to “Literary” Journalism: In Australia, Margaret Simons Challenges the Jargon While Producing the Texts by Sue Joseph 101 Leila Guerriero and the Uncertain Narrator by Pablo Calvi 119 Alexandra Fuller of Southern Africa: A White Woman Writer Goes West by Anthea Garman and Gillian Rennie 133 Scholar-Practitioner Q+A William Dow and Leonora Flis interview Barbara Ehrenreich 147 Book Reviews 159 ––––––––––––––––– Mission Statement 178 International Association for Literary Journalism Studies 179 2 Literary Journalism Studies Copyright © 2015 International Association for Literary Journalism Studies All rights reserved Website: www.literaryjournalismstudies.org Literary Journalism Studies is the journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies and is published twice yearly. For information on subscribing or membership, go to www.ialjs.org. Member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals Published twice a year, Spring and Fall issues.