The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manhattan Transference: Reader Itineraries in Modernist New York

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2013 Manhattan Transference: Reader Itineraries in Modernist New York Sophia Bamert Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Bamert, Sophia, "Manhattan Transference: Reader Itineraries in Modernist New York" (2013). Honors Papers. 308. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/308 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Sophia Bamert April 19, 2013 Oberlin College English Honors Paper Advisor: T.S. McMillin Manhattan Transference: Reader Itineraries in Modernist New York The development of transportation technologies played a vital role in New York City’s transformation into a modern metropolis. Between 1884 and 1893, travel by rapid transit in New York increased by 250 percent,1 and “by 1920 there were 2,365,000,000 riders annually on all city transit lines . twice as many as all the steam railroads in the country carried” (Michael W. Brooks 90). The Elevated trains, which were completed by 1880,2 and the subways, opened in 1904, fueled construction and crowding in the booming city,3 and they fundamentally altered the everyday experience of living in New York. These modern transit technologies were novel in and of themselves, but, moreover, they offered passengers previously unaccessible views of the urban landscape through which they moved: from above the streets on an Elevated track, from underground in a subway tunnel, and so on. -

Online Finding

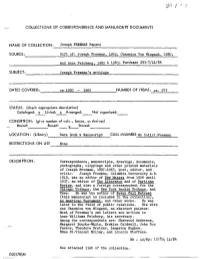

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Democratic Vanguardism

Democratic Vanguardism Modernity, Intervention, and the making of the Bush Doctrine Michael Harland A Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History University of Canterbury 2013 For Francine Contents Acknowledgements 1 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 1. America at the Vanguard: Democracy Promotion and the Bush Doctrine 16 2. Assessing History’s End: Thymos and the Post-Historic Life 37 3. The Exceptional Nation: Power, Principle and American Foreign Policy 55 4. The “Crisis” of Liberal Modernity: Neoconservatism, Relativism and Republican Virtue 84 5. An “Intoxicating Moment:” The Rise of Democratic Globalism 123 6. The Perfect Storm: September 11 and the coming of the Bush Doctrine 159 Conclusion 199 Bibliography 221 1 Acknowledgements Over the three years I spent researching and writing this thesis, I have received valuable advice and support from a number of individuals and organisations. My supervisors, Peter Field and Jeremy Moses, were exemplary. As my senior supervisor, Peter provided a model of a consummate historian – lively, probing, and passionate about the past. His detailed reading of my work helped to hone the thesis significantly. Peter also allowed me to use his office while he was on sabbatical in 2009. With a library of over six hundred books, the space proved of great use to an aspiring scholar. Jeremy Moses, meanwhile, served as the co-supervisor for this thesis. His research on the connections between liberal internationalist theory and armed intervention provided much stimulus for this study. Our discussions on the present trajectory of American foreign policy reminded me of the continuing pertinence of my dissertation topic. -

Nationality Issue in Proletkult Activities in Ukraine

GLOKALde April 2016, ISSN 2148-7278, Volume: 2 Number: 2, Article 4 GLOKALde is official e-journal of UDEEEWANA NATIONALITY ISSUE IN PROLETKULT ACTIVITIES IN UKRAINE Associate Professor Oksana O. GOMENIUK Ph.D. (Pedagogics), Pavlo TYchyna Uman State Pedagogical UniversitY, UKRAINE ABSTRACT The article highlights the social and political conditions under which the proletarian educational organizations of the 1920s functioned in the context of nationalitY issue, namelY the study of political frameworks determining the status of the Ukrainian language and culture in Ukraine. The nationalitY issue became crucial in Proletkult activities – a proletarian cultural, educational and literary organization in the structure of People's Commissariat, the aim of which was a broad and comprehensive development of the proletarian culture created by the working class. Unlike Russia, Proletkult’s organizations in Ukraine were not significantlY spread and ceased to exist due to the fact that the national language and culture were not taken into account and the contact with the peasants and indigenous people of non-proletarian origin was limited. KeYwords: Proletkult, worker, culture, language, policY, organization. FORMULATION OF THE PROBLEM IN GENERAL AND ITS CONNECTION WITH IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC AND PRACTICAL TASKS ContemporarY social transformations require detailed, critical reinterpreting the experiences of previous generations. In his work “Lectures” Hegel wrote that experience and history taught that peoples and governments had never learnt from history and did not act in accordance with the lessons that historY could give. The objective study of Russian-Ukrainian relations require special attention that will help to clarify the reasons for misunderstandings in historical context, to consider them in establishing intercommunication and ensuring peace in the geopolitical space. -

Winds of Change Are Normally Characterised by the Distinctive Features of a Geographical Area

Department of Military History Rekkedal et al. Rekkedal The various forms of irregular war today, such as insurgency, counterinsurgency and guerrilla war, Winds of Change are normally characterised by the distinctive features of a geographical area. The so-called wars of national liberation between 1945 and the late On Irregular Warfare 1970s were disproportionately associated with terms like insurgency, guerrilla war and (internal) Nils Marius Rekkedal et al. terrorism. Use of such methods signals revolutionary Publication series 2 | N:o 18 intentions, but the number of local and regional conflict is still relatively high today, almost 40 years after the end of the so-called ‘Colonial period’. In this book, we provide some explanations for the ongoing conflicts. The book also deals, to a lesser extent, with causes that are of importance in many ongoing conflicts – such as ethnicity, religious beliefs, ideology and fighting for control over areas and resources. The book also contains historical examples and presents some of the common thoughts and theories concerning different forms of irregular warfare, insurgencies and terrorism. Included are also a number of presentations of today’s definitions of military terms for the different forms of conflict and the book offer some information on the international military-theoretical debate about military terms. Publication series 2 | N:o 18 ISBN 978 - 951 - 25 - 2271 - 2 Department of Military History ISSN 1456 - 4874 P.O. BOX 7, 00861 Helsinki Suomi – Finland WINDS OF CHANGE ON IRREGULAR WARFARE NILS MARIUS REKKEDAL ET AL. Rekkedal.indd 1 23.5.2012 9:50:13 National Defence University of Finland, Department of Military History 2012 Publication series 2 N:o 18 Cover: A Finnish patrol in Afghanistan. -

Socialistic Vision of John Steinbeck and Dos Passos: Foucauldian Analysis of the Grapes of Wrath and Manhattan Transfer

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-7, Issue-6S5, April 2019 Socialistic Vision of John Steinbeck and Dos Passos: Foucauldian Analysis of the Grapes of Wrath and Manhattan Transfer Neha Puri, Aruna Bhat I. INTRODUCTION Abstract:America emerged as a super power after the World War I but people also witnessed the suffering and severe John Steinbeck and Dos Passos were greatly impacted by degradation of American life. The Wall Street Crash, the the revolutionary atmosphere of 1930s. No wonder, Depression and the growth of Capitalism brought untold Manhattan Transfer (1925) of Dos Passos and The Grapes miseries to the fruit pickers and the farmers in America. John of Wrath (1939)[35],[5],[17] of John Steinbeck explore Steinbeck was inspired by the radical philosophy of Karl Marx individual freedom in socialistic collectivism; both the who propounded the theory of class less society giving a novels describe their nostalgic search for individualism in dialectical relationship between the haves and haves not. John Steinbeck is seriously concerned with the struggle of the “free enterprise.” proletariat. Steinbeck’s novels written during the 1930’s and 1940’s display his strong understanding of the common Dos Passos expressed his concern for the loss of liberty of Communist principles. Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath is the the individuals in his article “America and the Pursuit of heartrending tale of how “farming became industry” (298), Happiness” published in Nation thus: “We must stop the depicting the sufferings of the farmers trapped in the Dust Bowl economic war, the war for the existence of man against of the twenties. -

The Courant Sponsored by the Syracuse University Library Associates ISSN 1554-2688

pecial Collectio n of the S ns Researc lleti h Cen A Bu ter number six spring 2007 THE COUraNT Sponsored by the Syracuse University Library Associates ISSN 1554-2688 Exhibition on the Case of Sacco and Vanzetti Will Be Unveiled for the Fall Semester of 2007 The Special Collections Research Center, as its contri- bution to the university’s Syracuse Symposium with its theme of justice commencing in the fall of 2007, will open an exhibition entitled The Never-Ending Wrong: The Execution of Sacco and Vanzetti based upon its consider- able content documenting the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti and the protests surrounding it. The two Italian anarchists were found guilty of murder in conjunction with an armed robbery in Massachusetts, condemned to death, and execut- ed in 1927. Due to the depth of our holdings in the area of radicalism as it manifested itself in literature and art, we are particularly well prepared to present the wide range of national and international protest that was generated by this sensational trial. As the image on this page attests, critics even likened it to the Salem witchcraft trials of 1692. The core of the exhibition consists of the printed ephem- era that was produced by the Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee and the other contemporary progressive orga- Political cartoon entitled Have a Chair! by Fred Ellis. (See nizations that could see only a travesty of justice in the pro- the piece on Ellis on page eight.) This appeared as one of his works published in The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti in Cartoons ceedings. -

In the Decade Immediately Following the Second World War, Many Of

‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Julian Tzara Nemeth August 2007 2 This thesis titled ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought by JULIAN TZARA NEMETH has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kevin Mattson Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract NEMETH, JULIAN TZARA., M.A, August 2007, History ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought (108 pp.) Director of Thesis: Kevin Mattson In the early years of the Cold War, more than one hundred American academics lost their jobs because university administrators suspected them of Communist Party membership. How did intellectuals respond to this crisis? Referring to contemporary books, articles, organizational statements, and correspondence, I argue that disputes over academic freedom helped shatter a tenuous liberal consensus, unite conservatives, and challenge defenses of professorial liberty among academia’s largest professional organization, the American Association of University Professors. Specifically, I show how Sidney Hook and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s dispute over academic freedom was representative of larger quarrels among liberals over McCarthyism. Conversely, I demonstrate that conservatives such as William Buckley Jr. and Russell Kirk overcame serious differences on academic freedom to present a united front against liberalism, in and outside of the academy. Finally, I show the difficulty an organization such as the AAUP encounters when defending professional values in a democratic society. -

Fund Og Forskning I Det Kongelige Biblioteks Samlinger

Særtryk af FUND OG FORSKNING I DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEKS SAMLINGER Bind 50 2011 With summaries KØBENHAVN 2011 UDGIVET AF DET KONGELIGE BIBLIOTEK Om billedet på papiromslaget se s. 169. Det kronede monogram på kartonomslaget er tegnet af Erik Ellegaard Frederiksen efter et bind fra Frederik III’s bibliotek Om titelvignetten se s. 178. © Forfatterne og Det Kongelige Bibliotek Redaktion: John T. Lauridsen med tak til Ivan Boserup Redaktionsråd: Ivan Boserup, Grethe Jacobsen, Else Marie Kofod, Erland Kolding Nielsen, Anne Ørbæk Jensen, Stig T. Rasmussen, Marie Vest Fund og Forskning er et peer-reviewed tidsskrift. Papir: Lessebo Design Smooth Ivory 115 gr. Dette papir overholder de i ISO 9706:1994 fastsatte krav til langtidsholdbart papir. Grafisk tilrettelæggelse: Jakob Kyril Meile Nodesats: Niels Bo Foltmann Tryk og indbinding: SpecialTrykkeriet, Viborg ISSN 0060-9896 ISBN 978-87-7023-085-8 SPEAKING OF IRONY: Bournonville, Kierkegaard, H.C. Andersen and the Heibergs1 by Colin Roth t must have been exciting for the ballet historian, Knud Arne Jür Igensen, to discover a Bournonville manuscript in the Royal Library’s collection which opens with what is clearly a reference to Søren Kier ke gaard.2 Though not mentioned by name, Kierkegaard is readily identifiable because his Master’s degree dissertation on ‘The Concept of Irony’ is explicitly referred to in the first sentence. It was right that the discovery was quickly shared with researchers at the Søren Kierke gaard Research Centre at Copenhagen’s University. This article is a study of the document, its context and especially of the references con cealed within it. A complete transcription of the Danish original and a new English translation appear as appendices, one of which should, ideally, be read first. -

The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin 1917-1929 2Nd Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION FROM LENIN TO STALIN 1917-1929 2ND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Edward Hallett Carr | 9780333993095 | | | | | The Russian Revolution from Lenin to Stalin 1917-1929 2nd edition PDF Book Philosophy Economic determinism Historical materialism Marx's dialectic Marx's method Philosophy of nature. Rosmer himself was conscripted in May and so could not attend the Zimmerwald conference held in Switzerland in September , when a first puny attempt was made to bring together the remnants of the antiwar Left. Aleksandr Kerensky, the prime…. Lenin was prepared to replace the Union he had originally proposed with a looser association in which the centralized powers might be limited to defense and international relations alone. Concerning the political disenfranchisement of the capitalist social-class in Bolshevik Russia, Lenin said that "depriving the exploiters of the franchise is a purely Russian question, and not a question of the dictatorship of the proletariat, in general. The Communists, therefore, are, on the one hand, practically the most advanced and resolute section of the working-class parties of every country, that section which pushes forward all others; on the other hand, theoretically, they have over the great mass of the proletariat the advantage of clearly understanding the lines of march, the conditions, and the ultimate general results of the proletarian movement. However, he ruled by terror, and millions of his own There are problems in the interpretation: Carr designates the overtrow of the Provisional Government as a coup; the inadequate control of workers in the nationalized industry does not derive from the inability of workers but from the given circumstances, etc. -

The Proud Decades America in War and Peace, 1941-1960 1St Edition Download Free

THE PROUD DECADES AMERICA IN WAR AND PEACE, 1941-1960 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John P Diggins | 9780393956566 | | | | | The Rise And Fall Of The American Left Diggins's interests ranged from the foundations of the United States to the postmodern world. Return to Book Page. Peter rated it it was amazing Jul 28, He was the author of more than a dozen books and thirty articles on widely varied subjects on American intellectual history. He earned a fellowship award from the Guggenheim Fellowship inbecame a resident scholar of the Rockefeller Foundation inand was nominated for the National book Award for History. To ask other readers questions about Ronald Reaganplease sign up. That was contrary to Diggins's personal experience of Reagan "standing for tear gas and police" [4] most likely in reference of the s Berkeley protests. Even if Reagan, like so many others, did The Proud Decades America in War and Peace fully envision exactly how communism would fall, he ended the cold war by creating what Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher insisted was the "essential trust" that would be necessary to allow the peaceful exit of the Soviet Union from history. Published February 17th by W. An obituary reported that Diggins "was "critical of the anticapitalist Left for seeing in the abolition of property an end to oppression" but also "critical of the antigovernment Right for seeing in the elimination of political 1941-1960 1st edition the end of tyranny and the restoration of liberty. Ask Seller a Question. Kristin-Leigh rated it did not like it Oct 02, Community Reviews.