NPM Georgia2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distribution: EG: Bank of Jandara Lake, Bolnisi, Burs

Subgenus Lasius Fabricius, 1804 53. L. (Lasius) alienus (Foerster, 1850) Distribution: E.G.: Bank of Jandara Lake, Bolnisi, Bursachili, Gardabani, Grakali, Gudauri, Gveleti, Igoeti, Iraga, Kasristskali, Kavtiskhevi, Kazbegi, Kazreti, Khrami gorge, Kianeti, Kitsnisi, Kojori, Kvishkheti, Lagodekhi Reserve, Larsi, Lekistskali gorge, Luri, Manglisi, Mleta, Mtskheta, Nichbisi, Pantishara, Pasanauri, Poladauri, Saguramo, Sakavre, Samshvilde, Satskhenhesi, Shavimta, Shulaveri, Sighnaghi, Taribana, Tbilisi (Mushtaidi Garden, Tbilisi Botanical Garden), Tetritskaro, Tkemlovani, Tkviavi, Udabno, Zedazeni (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1964a, b, 1966, 1967b, 1968, 1974a); W.G.: Abasha, Ajishesi, Akhali Atoni, Anaklia, Anaria, Baghdati, Batumi Botanical Garden, Bichvinta Reserve, Bjineti, Chakvi, Chaladidi, Chakvistskali, Eshera, Grigoreti, Ingiri, Inkiti Lake, Kakhaberi, Khobi, Kobuleti, Kutaisi, Lidzava, Menji, Nakalakebi, Natanebi, Ochamchire, Oni, Poti, Senaki, Sokhumi, Sviri, Tsaishi, Tsalenjikha, Tsesi, Zestaponi, Zugdidi Botanical Garden (Ruzsky, 1905; Karavaiev, 1926; Jijilashvili, 1974b); S.G.: Abastumani, Akhalkalaki, Akhaltsikhe, Aspindza, Avralo, Bakuriani, Bogdanovka, Borjomi, Dmanisi, Goderdzi Pass, Gogasheni, Kariani, Khanchali Lake, Ota, Paravani Lake, Sapara, Tabatskuri, Trialeti, Tsalka, Zekari Pass (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1967a, 1974a). 54. L. (Lasius) brunneus (Latreille, 1798) Distribution: E.G.: Bolnisi, Gardabani, Kianeti, Kiketi, Manglisi, Pasanauri (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1968, 1974a); W.G.: Akhali Atoni, Baghdati, -

YOUTH POLICY IMPLEMENTATION at the LOCAL LEVEL: IMERETI and TBILISI © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung

YOUTH POLICY IMPLEMENTATION AT THE LOCAL LEVEL: IMERETI AND TBILISI © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung This Publication is funded by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung. Commercial use of all media published by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is not permitted without the written consent of the FES. YOUTH POLICY IMPLEMENTATION AT THE LOCAL LEVEL: IMERETI AND TBILISI Tbilisi 2020 Youth Policy Implementation at the Local Level: Imereti and Tbilisi Tbilisi 2020 PUBLISHERS Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, South Caucasus South Caucasus Regional Offi ce Ramishvili Str. Blind Alley 1, #1, 0179 http://www.fes-caucasus.org Tbilisi, Georgia Analysis and Consulting Team (ACT) 8, John (Malkhaz) Shalikashvili st. Tbilisi, 0131, Georgia Parliament of Georgia, Sports and Youth Issues Committee Shota Rustaveli Avenue #8 Tbilisi, Georgia, 0118 FOR PUBLISHER Felix Hett, FES, Salome Alania, FES AUTHORS Plora (Keso) Esebua (ACT) Sopho Chachanidze (ACT) Giorgi Rukhadze (ACT) Sophio Potskhverashvili (ACT) DESIGN LTD PolyGraph, www.poly .ge TYPESETTING Gela Babakishvili TRANSLATION & PROOFREADING Lika Lomidze Eter Maghradze Suzanne Graham COVER PICTURE https://www.freepik.com/ PRINT LTD PolyGraph PRINT RUN 150 pcs ISBN 978-9941-8-2018-2 Attitudes, opinions and conclusions expressed in this publication- not necessarily express attitudes of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung does not vouch for the accuracy of the data stated in this publication. © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung 2020 FOREWORD Youth is important. Many hopes are attached to the “next generation” – societies tend to look towards the young to bring about a value change, to get rid of old habits, and to lead any country into a better future. -

Interviu Saqartvelos Mecnierebata Erovnuli Akademiis Prezidenttan

zamTari WINTER interviu saqarTvelos mecnierebaTa erovnuli akademiis prezidentTan INTERVIEW WITH THE PRESIDENT OF GEORGIAN # NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES 6 2 0 1 4 saqarTvelos inteleqtualuri sakuTrebis erovnuli centris saqpatentis perioduli gamocema saqarTvelo gamodis sam TveSiIerTxel © saqpatenti, 2014 PERIODICAL PUBLICATION OF NATIONAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CENTER OF GEORGIA “SAKPATENTI” GEORGIA PUBLISHED QUARTERLY PRINTED AT SAKPATENTI PUBLISHING HOUSE ADDRESS: 0179 TBILISI, NINO RAMISHVILI STR. 31 © SAKPATENTI, 2014 TEL.: (+995 32) 291-71-82 [email protected] Tavmjdomaris sveti CHAIRMAN’S COLUMN Zvirfaso mkiTxvelo, ukve meore welia, wlis bolos, warmogidgenT Cveni Jurna lis saaxalwlo nomers. rogorc yovelTvis, am gamocemaSic Tavmoyrilia rubrikebi cnobili sasaqonlo niSnis, mniS vnelovani gamogonebis, dizainis, saavtoro uflebebisa da mkiTxvelisaTvis saintereso bevri sxva Temis Sesaxeb. es no meric gansakuTrebulia Tavisi sadResaswaulo ganwyobiTa da specialurad misTvis Seqmnili statiebiT Cveni qveynis inteleqtualur simdidreze. wlis bolos yovelTvis Tan axlavs gasuli wlis saqpa tentis saqmianobis Sefaseba. vfiqrob, rom inteleqtualuri sakuTrebis sferoSi 2013 wels erTerTi mniSvnelovani mov lena iyo JenevaSi inteleqtualuri sakuTrebis msoflio Dear reader, organizaciis (WIPO) rigiT 51e generalur asambleaze It is for the second time as we present the New Year’s edition of our magazine. As usual, this edition under different saqarTvelos kulturuli RonisZiebis gamarTva. RonisZie headings includes articles on well-known trademarks, signifi- -

The Situation in Human Rights and Freedoms in Georgia – 2011

2011 The Public Defender of Georgia ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PUBLIC DefeNDER OF GeorgIA 1 The views of the publication do not necessarily represent those of the Council of Europe. The report was published with financial support of the Council of Europe project, “Denmark’s Georgia Programme 2010-2013, Promotion of Judicial Reform, Human and Minority Rights”. 2 www.ombudsman.ge ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GeorgIA THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS IN GEORGIA 2011 2011 THE PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GeorgIA ANNUAL REPORT OF THEwww.ombudsman.ge PUBLIC DefeNDER OF GeorgIA 3 OFFICE OF PUBLIC DEFENDER OF GEORGIA 6, Ramishvili str, 0179, Tbilisi, Georgia Tel: +995 32 2913814; +995 32 2913815 Fax: +995 32 2913841 E-mail: [email protected] 4 www.ombudsman.ge CONTENTS INtrodUCTION ..........................................................................................................................7 JUDICIAL SYSTEM AND HUMAN RIGHTS ........................................................................11 THE RIGHT TO A FAIR TRIAL ........................................................................................11 ENFORCEMENT OF COUrt JUDGMENTS ...............................................................37 PUBLIC DEFENDER AND CONSTITUTIONAL OVERSIGHT ...........................41 LAW ENFORCEMENT BODIES AND HUMAN RIGHTS .......................................46 CIVIL-POLITICAL RIGHTS ..................................................................................................51 FREEDOM OF ASSEMBLY AND MANIFESTATIONS ............................................51 -

ELECTION CODE of GEORGIA As of 24 July 2006

Strasbourg, 15 November 2006 CDL(2006)080 Engl. only Opinion No. 362 / 2005 EUROPEAN COMMISSION FOR DEMOCRACY THROUGH LAW (VENICE COMMISSION) ELECTION CODE OF GEORGIA as of 24 July 2006 This is an unofficial translation of the Unified Election Code of Georgia (UEC) which has been produced as a reference document and has no legal authority. Only the Georgian language UEC has any legal standing. Incorporating Amendments adopted on: 28.11.2003 16.09.2004 Abkhazia and Adjara, Composition election admin; 12.10.2004 VL, Campaign funding, voting and counting procedures, observers’ rights, complaints and appeals, election cancellation and re-run 26.11.2004 Abolition of turnout requirement for mid-term elections and re-runs, drug certificate for MPs 24.12.2004 Rules for campaign and the media 22.04.2005 VL; CEC, DEC, PEC composition and functioning; 23.06.2005 Deadlines and procedures for filing complaints 09.12.2005 Election of Tbilisi Sacrebulo; plus miscellaneous minor changes 16.12.2005 Campaign fund; media outlets 23.12.2005 (1) Election System for Parliament, Multi-mandate Districts, Mid-term Elections, PEC, 23.12.2005 (2) Election of Sacrebulos (except Tbilisi) 06.2006 Changes pertaining to local elections; voting procedures, etc. 24.07.2006 Early convocation of PEC for 2006 local elections ORGANIC LAW OF GEORGIA Election Code of Georgia CONTENTS PART I............................................................................................................................................................................................ -

2019 Migration Profile of Georgia

State Commission on Migration Issues 2019 Migration Profile of Georgia 2019 Tbilisi, Georgia Unofficial Translation State Commission on Migration Issues The European Union for Georgia This publication was produced in the framework of the project “Support to Sustained Effective Functioning of the State Commission on Migration Issues”, funded by the European Union. The contents of this publication in no way represent the views of the European Union. Contents List of Acronyms and Abbreviations1 Association Agreement between the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community and their Member States, of the one part, and Georgia, of the other part Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) between Georgia and EU “Enhancing Georgia’s Migration Management 2” European Migration Network /EC/ Statistical Office of the European Union GDP Gross Domestic Product National Statistics Office of Georgia Human Development Index International Centre for Migration Policy Development IDP Internally Displaced Person International Organization for Migration Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia Ministry of Education, Science, Culture And Sport of Georgia Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia National Agency of Public Registry Policy and Management Consulting Group Public Service Development Agency State Commission on Migration -

Report, on Municipal Solid Waste Management in Georgia, 2012

R E P O R T On Municipal Solid Waste Management in Georgia 2012 1 1 . INTRODUCTION 1.1. FOREWORD Wastes are one of the greatest environmental chal- The Report reviews the situation existing in the lenges in Georgia. This applies both to hazardous and do- field of municipal solid waste management in Georgia. mestic wastes. Wastes are disposed in the open air, which It reflects problems and weak points related to munic- creates hazard to human’s health and environment. ipal solid waste management as related to regions in Waste represents a residue of raw materials, semi- the field of collection, transportation, disposal, and re- manufactured articles, other goods or products generat- cycling. The Report also reviews payments/taxes re- ed as a result of the process of economic and domestic lated to the waste in the country and, finally, presents activities as well as consumption of different products. certain recommendations for the improvement of the As for waste management, it generally means distribu- noted field. tion of waste in time and identification of final point of destination. It’s main purpose is reduction of negative impact of waste on environment, human health, or es- 1.2. Modern Approaches to Waste thetic condition. In other words, sustainable waste man- Management agement is a certain practice of resource recovery and reuse, which aims to the reduction of use of natural re- The different waste management practices are ap- sources. The concept of “waste management” includes plied to different geographical or geo-political locations. the whole cycle from the generation of waste to its final It is directly proportional to the level of economic de- disposal. -

Social Screening of Subprojects

Public Disclosure Authorized Gas Supply and Access Road Rehabilitation for Vartsikhe Cellar LTD in Village Vartsikhe, Baghdati Municipality Public Disclosure Authorized Sub-Project Environmental and Social Screening and Environmental Management Plan Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD BANK FINANCED SECOND REGIONAL AND MUNICIPAL INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (SRMIDP) Public-Private Investment (PPI) Public Disclosure Authorized November 2018 The Sub-Project Description The Subproject (SP) site is located in village Vartsikhe, Baghdati municipality, Imereti region, Western Georgia. The SP includes rehabilitation of a 775-meter-long road from Vartsikhe-Didveli motorway main road to the Vartsikhe Cellar. The road is registered as a municipal property (with the cadastral code: 30.06.33.008) and the road bed does not overlap with the privately-owned agricultural land plots under vineyards and other crops located on the sides of the road, so works will be completed within the ROW. Furthermore, contractor does not need any access to the adjacent lands to complete the civil works. No residential houses are located at the road sides. The road to be rehabilitated is in a very poor condition. The first half section is covered with ground and gravel surface, while another half has no cover and only traces of car tires are visible marks of the road bed. According to the SP design, the road will be covered by asphalt and road signs will be arranged. Along the road, there are two culverts, one of them is in a satisfactory condition and one pipe needs to be repaired. The road will be rehabilitated within the following parameters: the width of the carriageway - 6.0m; the width of the shoulders - 0.5m. -

GEORGIA Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation

GEORGIA Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation Council of Europe Original: Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation in Georgia (English version) The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. The reproduction of extracts (up to 500 words) is authorised, except for commercial purposes as long as the integrity of the text is preserved, the excerpt is not used out of context, does not provide incomplete information or does not otherwise mislead the reader as to the nature, scope or content of the text. The source text must always be acknowledged as follows All other requests concerning the reproduction/translation of all or part of the document, should be addressed to the Directorate of Communications, Council of Europe (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]). All other requests concerning this publication should be addressed to the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe. Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of the Council of Europe Cover design and layout: RGOLI F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex France © Council of Europe, December 2020 E-mail: [email protected] (2nd edition) Acknowledgements This Handbook on Transparency and Citizen Participation in Georgia was developed by the (2015-2017) in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova, Ukraine and Belarus. It was implemented as part of the Partnership for Good Governance 2015-2017 between the Council of Europe and the European Union. The research work and writing of this updated edition was carried out by the Institute for Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI), a Georgian non-governmental organisation. -

Kutaisi Investment Catalogue

Kutaisi has always been attractive for innovative projects with its historic and cultural importance. In order to succeed, any business must have a stable and reliable environment, and it can be eagerly said that our city is a springboard for it. An investor thinks what kind of comfort he or she will have with us. Kutaisi is ready to share examples of successful models of the world and promote business development. Giorgi Chigvaria Mayor of Kutaisi 1 Contact Information City Hall of Kutaisi Municipality Rustaveli Avenue 3, Kutaisi. George Giorgobiani [Position] Mobile: +995 551 583158 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kutaisi.gov.ge Imereti Regional Chamber of Commerce and Industry Emzar Gvinianidze Rustaveli Avenue 124, Kutaisi. Phone: +995 431 271400/271401 Mobile: +995 577 445484/597 445484 Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Disclaimer: This catalogue is prepared by international expert Irakli Matkava with support of the USAID Good Governance Initiative (GGI). The author’s views expressed in the publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the US Agency for International Development, GGI or the US Government. 2 What can Kutaisi offer? Business development opportunities - Kutaisi is the main of western Georgia offering access to a market of 900,000 customers, low property prices and labour costs, and multimodal transport infrastructure that is also being upgraded and expanded. Infrastructure projects for business development - Up to 1 billion GEL is being spent on the modernization of the city’s infrastructure, enabling Kutaisi to become a city of with international trade and transit role and markedly boosting its tourism potential. -

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Presidential Election, Georgia – 4 January 2004 STATEMENT of PRELIMINARY FINDINGS and CONCLUSIONS

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT PA THE ORGANIZATION FOR SECURITY AND CO-OPERATION IN EUROPE PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Presidential Election, Georgia – 4 January 2004 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS Tbilisi, 5 January 2004 - The International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) for the 4 January extraordinary presidential election in Georgia is a joint undertaking of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (OSCE PA), the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), and the European Parliament (EP). This preliminary statement is issued prior to the tabulation and announcement of official election results and before election day complaints and appeals have been addressed. A complete and final analysis of the election process will be offered in the OSCE/ODIHR Final Report. PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS AND SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS The 4 January 2004 extraordinary presidential election in Georgia demonstrated notable progress over previous elections, and brought the country closer to meeting international commitments and standards for democratic elections. The authorities generally displayed the collective political will to conduct democratic elections, especially compared to the 2 November 2003 parliamentary elections that were characterized by systematic and widespread fraud. Nevertheless, due to the short timeframe available for the organization of the election and the lack of a truly competitive political environment, the forthcoming parliamentary elections will be a more genuine indicator of Georgia’s commitment to a democratic election process. The Central Election Commission (CEC) made commendable efforts to administer this election in a credible and professional manner, although the time constraints limited the scope of administrative improvements. -

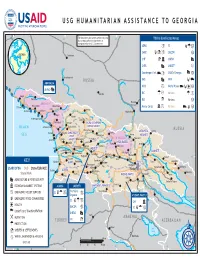

Georgia Program Maps 10/31/2008

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO GEORGIA 40° E 42° E The boundaries and names used on this map 44° E T'bilisi & Affected46° E Areas Majkop do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. ADRA a SC Ga I GEORGIA CARE a UMCOR a Cherkessk CHF IC UNFAO CaspianA Sea 44° CNFA A UNICEF J N 44° Kuban' Counterpart Int. Ea USAID/Georgia Aa N Karachayevsk RUSSIA FAO A WFP E ABKHAZIA E !0 Psou IOCC a World Vision Da !0 UNFAO A 0 Nal'chik IRC G J Various G a ! Gagra Bzyb' Groznyy RUSSIA 0 Pskhu IRD I Various a ! Nazran "ABKHAZIA" Novvy Afon Pitsunda 0 Omarishara Mercy Corps Ca Various E a ! Lata Sukhumi Mestia Gudauta!0 !0 Kodori Inguri Vladikavkaz Otap !0 Khaishi Kvemo-gulripsh Lentekhi !0 Tkvarcheli Dzhvari RACHA-LECHKHUMI-RACHA-LECHKHUMI- Terek BLACK Ochamchira Gali Tsalenjhikha KVEMOKVEMO SVANETISVANETI RUSSIA Khvanchkara Rioni MTSKHETA-MTSKHETA- Achilo Pichori Zugdidi SAMEGRELO-SAMEGRELO- Kvaisi Mleta SEA ZEMOZEMO Ambrolauri MTIANETIMTIANETI Pasanauri Alazani Khobi Tskhaltubo Tkibuli "SOUTH OSSETIA" Anaklia SVANETISVANETI Aragvi Qvirila SHIDASHIDA KARTLIKARTLI Senaki Kurta Artani Rioni Samtredia Kutaisi Chiatura Tskhinvali Poti IMERETIIMERETI Lanchkhuti Rioni !0 Akhalgori KAKHETIKAKHETI Chokhatauri Zestafoni Khashuri N Supsa Baghdati Dusheti N 42° Kareli Akhmeta Kvareli 42° Ozurgeti Gori Kaspi Borzhomi Lagodekhi KEY Kobuleti GURIAGURIA Bakhmaro Borjomi TBILISITBILISI Telavi Abastumani Mtskheta Gurdzhaani Belokany USAID/OFDA DoD State/EUR/ACE Atskuri T'bilisi Î! Batumi 0 AJARIAAJARIA Iori ! Vale Akhaltsikhe Zakataly State/PRM