Realizing the Urban Potential in Georgia: National Urban Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defusing Conflict in Tsalka District of Georgia: Migration, International Intervention and the Role of the State

Defusing Conflict in Tsalka District of Georgia: Migration, International Intervention and the Role of the State Jonathan Wheatley ECMI Working Paper #36 October 2006 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor) D-24939 Flensburg Germany +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper #36 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Dr. Marc Weller Copyright 2006 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Published in October 2006 by the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) ISSN: 1435-9812 2 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................................... 4 II. TSALKA DISTRICT: AN OVERVIEW................................................................................................................... 5 ECONOMY AND INFRASTRUCTURE .................................................................................................................................. 5 DEMOGRAPHY AND MIGRATION ..................................................................................................................................... 8 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS AND THE ROLE OF THE STATE........................................................................................... 11 III. MAIN ARENAS OF CONFLICT IN TSALKA DISTRICT................................................................................ 14 INTER-COMMUNAL CONFLICT AT LOCAL LEVEL -

43405-025: Urban Services Improvement Investment Program

Initial Environmental Examination ______________________________________ March 2021 Georgia: Urban Services Improvement Investment Program – Tranche 3 Construction of Abasha Water Supply System Sub-Project (ABA-01) (Variation Order #03) Prepared by United Water Supply Company of Georgia LLC for the Ministry of Regional Development and Infrastructure of Georgia and the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 2 Supplementary IEE Project Number: 43405-025 GEO: Urban Services Improvement Investment Program (USIIP/T3) CONSTRUCTION OF ABASHA WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM SUB- PROJECT (ABA-01) (VARIATION ORDER #03) 3 2021 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DEPP Department of Environmental protection and Permits EA Executing Agency EARF Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EHS Environmental Health & Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIP Environmental Impact Permit EMP/ Environmental Management Plan/ Site-Specific Environmental Management Plan SSEMP ES/ SES Environmental -

Working Paper March 2021 #12

GIP W O R K I N G P A P E R MARCH 2021 #12 GOVERNMENTAL ENTITIES OF ABKHAZIA AND THE FORMER AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT OF SOUTH OSSETIA IN TBILISI: POWER AND LEGITIMACY IN EXILE Tornike Zurabashvili P I GEORGIAN INSTITUTE G OF POLITICS GIP WORKING PAPER MARCH 2021 #12 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Tornike Zurabashvili has a lengthy experience of working for non-governmental organizations and think tanks in Georgia and abroad. In 2017-2019, he was the Chief Editor of Civil.Ge, a trilingual online outlet on politics of Georgia. In 2019-2020, Tornike was a fellow of the Eurasia Democratic Security Network at the Center for Social Sciences in Tbilisi. He is currently the Programs Manager at the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED), an elections and democracy watchdog in Georgia. Tornike holds a Bachelor’s degree from Tbili si State University (International Affairs), and Master’s degrees from Ilia State University (Public Administration) and Trinity College Dublin (Political Science). He has also completed exchange and short-term programs at Charles, Tartu and Georgetown universities. He is currently pursuing a PhD in political science at Tbilisi State University. The original text is published in Georgian; Available here >> Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) is a Tbilisi-based non-profit, non-partisan, research and analysis organization. GIP works to strengthen the organizational backbone of democratic institutions and promote good governance and development through policy research and advocacy in Georgia. This publication was produced as part of the research project Competency through Cooperation: Advancing knowledge on Georgia’s strategic path — GEOPATH funded by the Research Council of Norway. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA November 15-17 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: November 18, 2019 Occupied Regions Tskhinvali Region (so called South Ossetia) 1. Tskhinvali Sends Detained Georgian Doctor to Pretrial Custody Tbilisi-based doctor, Vazha Gaprindashvili, who was detained by Russia-backed Tskhinvali region‟s “state security committee” near the occupation line with Akhalgori Municipality several days ago, was sentenced to pretrial custody, the Georgian State Security Service confirmed. According to media reports, prior to calling his wife and saying he was detained and transferred to Tskhinvali, Vazha Gaprindashvili told his family on November 9 that he was leaving Tbilisi for some business (Civil.ge, November 15, 2019). 2. President Calls for Releasing Georgian Doctor Detained in Tskhinvali Georgian President Salome Zurabishvili calls on the heads of international organizations “to use all available means” to achieve the release of Georgian doctor Vazha Gaprindashvili. Gaprindashvili, who “arrived in the [occupied Tskhinvali] region to perform his professional duties,” was detained near the occupation line with Akhalgori Municipality and later sentenced to pretrial custody in Tskhinvali. In a statement, the President noted that “there is a severe crisis in the occupied Tskhinvali region and it has become even sharper today.” Therefore, Zurabishvili called on the heads of international organizations to take necessary measures to improve the situation on the ground (Civil.ge, November 16, 2019). 3. Georgian MFA Statement on Doctor Gaprindashvili’s Detention in Tskhinvali Georgian Foreign Ministry reported on November 16 that it is “using all of its diplomatic tools” aimed at suspending illegal processes on occupied territories and improving human rights situation on the ground. -

Assemblée Générale Distr

Nations Unies A/HRC/13/21/Add.3 Assemblée générale Distr. générale 14 janvier 2010 Français Original: anglais Conseil des droits de l’homme Treizième session Point 3 de l’ordre du jour Promotion et protection de tous les droits de l’homme, civils, politiques, économiques, sociaux et culturels, y compris le droit au développement Rapport soumis par le Représentant du Secrétaire général pour les droits de l’homme des personnes déplacées dans leur propre pays, Walter Kälin* Additif Suite donnée au rapport sur la mission en Géorgie (A/HRC/10/13/Add.2)** * Soumission tardive. ** Le résumé du présent rapport est distribué dans toutes les langues officielles. Le rapport, qui est joint en annexe au résumé, n’est distribué que dans la langue originale. GE.10-10252 (F) 250110 260110 A/HRC/13/21/Add.3 Résumé Le Représentant du Secrétaire général pour les droits de l’homme des personnes déplacées dans leur propre pays s’est rendu, les 5 et 6 novembre 2009, dans la région de Tskhinvali (Ossétie du Sud) afin de donner suite à la mission qu’il avait effectuée en Géorgie en octobre 2008. Il a pu avoir accès à toutes les zones qu’il avait demandé à voir, y compris à la région de Tskhinvali et aux districts d’Akhalgori et de Znauri, et il a tenu des consultations franches et ouvertes avec les autorités de facto d’Ossétie du Sud. En raison du conflit d’août 2008, 19 381 personnes ont été déplacées au-delà de la frontière de facto, tandis que, selon les estimations, entre 10 000 et 15 000 personnes ont été déplacées à l’intérieur de la région de Tskhinvali (Ossétie du Sud). -

Overview of Cases on Restriction of Religious Freedoms and Discrimination

Overview of Cases on Restriction of Religious Freedoms and Discrimination The present report was prepared in the framework of the project – “Increasing Access to Justice for დოკუმენტი მომზადებულია პროექტის „მართლმსაჯულების ხელმისაწვდომობის გაძლიერება Discriminated Religious Communities“ - financed by the program “Promoting Rule of Law in Georgia დისკრიმინირებული რელიგიური თემებისთვის” ფარგლებში, რომელიც ხორციელდება (PROLoG) implemented by the East-West Management Institute (EWMI). ამერიკის შეერთებული შტატების საერთაშორისო განვითარების სააგენტოს (USAID) მხარდაჭერით, აღმოსავლეთ - დასავლეთის მართვის ინსტიტუტის (EWMI)-ის პროგრამის The report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for „კანონის უზენაესობის მხარდაჭერა საქართველოში“ (PROLoG) ფარგლებში. International Development (USAID). Responsibility for the content of the report lies entirely with the authors.მიმოხილვაში Views expressedგამოთქმული in this მოსაზრება publication შესაძლოაdo not necessarily არ გამოხატავდეს reflect the viewsUSAID of -theის U.Sპოზიციას Government. orშესაბამისად United States, USAID Agency არ forარის International პასუხისმგებელი Development. მასალის შინაარსზე. ხელმძღვანელი: თამთა მიქელაძე ავტორები: მარიამ ბეგაძე, ეთო გვრიტიშვილი, ქეთი ჩუთლაშვილი რედაქტორი: ლაშა ქავთარაძე დიზაინერი: თორნიკე ლორთქიფანიძე გარეკანი: სალომე ლაცაბიძე აკრძალულია აქ მოყვანილი მასალების გადაბეჭდვა, გამრავლება ან გავრცელება კომერციული მიზნით, ცენტრის წერილობითი ნებართვის გარეშე. ადამიანის უფლებების სწავლებისა და მონიტორინგის ცენტრი (EMC) მისამართი: -

Economic Prosperity Initiative

USAID/GEORGIA DO2: Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth October 1, 2011 – September 31, 2012 Gagra Municipal (regional) Infrastructure Development (MID) ABKHAZIA # Municipality Region Project Title Gudauta Rehabilitation of Roads 1 Mtskheta 3.852 km; 11 streets : Mtskheta- : Mtanee Rehabilitation of Roads SOKHUMI : : 1$Mestia : 2 Dushet 2.240 km; 7 streets :: : ::: Rehabilitation of Pushkin Gulripshi : 3 Gori street 0.92 km : Chazhashi B l a c k S e a :%, Rehabilitaion of Gorijvari : 4 Gori Shida Kartli road 1.45 km : Lentekhi Rehabilitation of Nationwide Projects: Ochamchire SAMEGRELO- 5 Kareli Sagholasheni-Dvani 12 km : Highway - DCA Basisbank ZEMO SVANETI RACHA-LECHKHUMI rehabilitaiosn Roads in Oni Etseri - DCA Bank Republic Lia*#*# 6 Oni 2.452 km, 5 streets *#Sachino : KVEMO SVANETI Stepantsminda - DCA Alliance Group 1$ Gali *#Mukhuri Tsageri Shatili %, Racha- *#1$ Tsalenjikha Abari Rehabilitation of Headwork Khvanchkara #0#0 Lechkhumi - DCA Crystal Obuji*#*# *#Khabume # 7 Oni of Drinking Water on Oni for Nakipu 0 Likheti 3 400 individuals - Black Sea Regional Transmission ZUGDIDI1$ *# Chkhorotsku1$*# ]^!( Oni Planning Project (Phase 2) Chitatskaro 1$!( Letsurtsume Bareuli #0 - Georgia Education Management Project (EMP) Akhalkhibula AMBROLAURI %,Tsaishi ]^!( *#Lesichine Martvili - Georgia Primary Education Project (G-Pried) MTSKHETA- Khamiskuri%, Kheta Shua*#Zana 1$ - GNEWRC Partnership Program %, Khorshi Perevi SOUTH MTIANETI Khobi *# *#Eki Khoni Tskaltubo Khresili Tkibuli#0 #0 - HICD Plus #0 ]^1$ OSSETIA 1$ 1$!( Menji *#Dzveli -

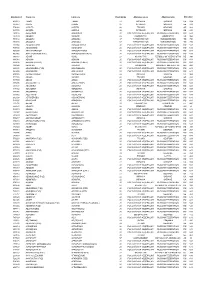

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Number of Libraries 1 Akaki Tsereteli State University 2 Batumi

№ Number of libraries 1 Akaki Tsereteli State University 2 Batumi Navigation Teaching University 3 Batumi Shota Rustaveli State University 4 Batumi State Maritime Academy 5 Business and Technology University 6 Caucasus International University 7 Caucasus University 8 Collage Iberia 9 David Agmashenebeli University of Georgia 10 David Tvildiani Medical University 11 East European University 12 European University 13 Free Academy of Tbilisi 14 Georgian American University (GAU) 15 Georgian Aviation University 16 Georgian Patriarchate Saint Tbel Abuserisdze Teaching University 17 Georgian state teaching university of physical education and sport education and sport 18 Georgian Technical University 19 Gori State Teaching University 20 Guram Tavartkiladze Tbilisi Teaching University 21 Iakob Gogebashvili Telavi State University 22 Ilia State University 23 International Black Sea University 24 Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts 25 Kutaisi Ilia Tchavtchavadze Public Library 26 LEPL - Vocational College "Black Sea" 27 LEPL Vocational College Lakada 28 LTD East-West Teaching University 29 LTD Kutaisi University 30 LTD Schllo IB Mtiebi 31 LTD Tbilisi Free School 32 National Archives of Georgia 33 National University of Georgia (SEU) 34 New Higher Education Institute 35 New Vision University (NVU) 36 Patriarchate of Georgia Saint King Tamar University 37 Petre Shotadze Tbilisi Medical Academy 38 Public Collage MERMISI 39 Robert Shuman European School 40 Samtskhe-Javakheti State Teaching University 41 Shota Meskhia Zugdidi State Teaching University 42 Shota Rustaveli theatre and Film Georgia State University 43 St. Andrews Patriarchate Georgian University 44 Sulkhan-Saba Orbeliani University 45 Tbilisi Humanitarian Teaching University 46 Tbilisi open teaching University 47 Tbilisi State Academy of Arts 48 Tbilisi State Medical University (TSMU) 49 TSU National Scientific Library. -

Ethnobiology of Georgia

SHOTA TUSTAVELI ZAAL KIKVIDZE NATIONAL SCIENCE FUNDATION ILIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS ETHNOBIOLOGY OF GEORGIA ISBN 978-9941-18-350-8 Tbilisi 2020 Ethnobiology of Georgia 2020 Zaal Kikvidze Preface My full-time dedication to ethnobiology started in 2012, since when it has never failed to fascinate me. Ethnobiology is a relatively young science with many blank areas still in its landscape, which is, perhaps, good motivation to write a synthetic text aimed at bridging the existing gaps. At this stage, however, an exhaustive representation of materials relevant to the ethnobiology of Georgia would be an insurmountable task for one author. My goal, rather, is to provide students and researchers with an introduction to my country’s ethnobiology. This book, therefore, is about the key traditions that have developed over a long history of interactions between humans and nature in Georgia, as documented by modern ethnobiologists. Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my colleagues – Rainer Bussmann, Narel Paniagua Zambrana, David Kikodze and Shalva Sikharulidze for the exciting and fruitful discussions about ethnobiology, and their encouragement for pushing forth this project. Rainer Bussmann read the early draft of this text and I am grateful for his valuable comments. Special thanks are due to Jana Ekhvaia, for her crucial contribution as project coordinator and I greatly appreciate the constant support from the staff and administration of Ilia State University. Finally, I am indebted to my fairy wordmother, Kate Hughes whose help was indispensable at the later stages of preparation of this manuscript. 2 Table of contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. A brief introduction to ethnobiology...................................................................................... -

2.1.1~2.1.4 95/06/12

Appendices Appendix-1 Member List of the Study Team (1) Field Survey 1. Dr. Yoshiko TSUYUKI Team Leader/ Technical Official, Experts Service Division, Technical Advisor Bureau of International Cooperation International Medical Center of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2. Mr. Hideo EGUCHI Security Control Deputy Resident Representative, Planner United Kingdom Office (JICA) 3. Mr. Yoshimasa TAKEMURA Project Coordinator Staff, Second Management Division, Grant Aid Management Department (JICA) 4. Mr. Yoshiharu HIGUCHI Project Manager CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 5. Dr. Tomoyuki KURODA Health Sector Surveyor CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 6. Mr. Hiroshi MORII Equipment Planner CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 7. Mr. Haruo ITO Equipment Planner / CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. Cost and Procurement Planner 8. Ms. Rusudan PIRVELI Interpreter CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. (2) Explanation of Draft Report 1. Dr. Yoshiko TSUYUKI Team Leader/ Technical Official, Experts Service Division, Technical Advisor Bureau of International Cooperation International Medical Center of Japan, Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2. Mr. Yoshimasa TAKEMURA Project Coordinator Staff, Second Management Division, Grant Aid Management Department (JICA) 3. Mr. Yoshiharu HIGUCHI Project Manager CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 4. Mr. Hiroshi MORII Equipment Planner CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. 5. Ms. Rusudan PIRVELI Interpreter CRC Overseas Cooperation Inc. A-1 Appendix-2 Study Schedule (1) Field Survey No. Date Movement Activities Accommodation 1 Apr. 5 (Sat) Narita→Frankfurt Frankfurt (A) (B) (D) (A) (C) (D) 2 Apr. 6 (Sun) Frankfurt→Baku Baku (A) (C) (D) (A) (C) (D) 3 Apr. 7 (Mon) Baku→A) (C) (D) Visit the Embassy of Japan in Baku Train (A) (C) (D) London→(B) (A) (C) (D) Flight (B) (F) (G) Narita→Vienna→ (F) (G) 4 Apr. -

ELKANA/FAO Workshop on EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION

ELKANA/FAO Workshop on EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION MANAGEMENT AMONG AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH, EXTENSION AND FARMERS FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN GEORGIA organized by the Biological Farming Association “ELKANA”, Georgia and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 1-3 February 2005 Tbilisi, Georgia TABLE OF CONTENT EXECUT IVE S UMM ARY ...................................................................................................... 4 ACKNO WLEDG EM ENTS ..................................................................................................... 6 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND................................................................... 7 2. PRESENTATIONS........................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Participants............................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Programme of the workshop .................................................................................. 7 2.3 Summary of presentations and discussions............................................................ 9 2.4 SWOT Analysis.................................................................................................... 11 2.5 Developing ideas for cooperation......................................................................... 13 2.6 Session A. Drafting a project outline by group representatives........................... 13 2.7 Conclusions and Recommendations of the Workshop........................................