Guanyin Goddess of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-Day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions Isabelle Charleux

Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions Isabelle Charleux To cite this version: Isabelle Charleux. Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions. Sino-Tibetan Buddhism across the Ages, 5, 2021, Studies on East Asian Religions. halshs-03327320 HAL Id: halshs-03327320 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03327320 Submitted on 27 Aug 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Isabelle Charleux. Authors’ own file, not the published version in Sino-Tibetan Buddhism across the Ages, Ester Bianchi & Shen Weirong (dir.), Brill : Leyde & Boston (Studies on East Asian Religious, vol. 5), 2021 Tibeto-Mongol and Chinese Buddhism in Present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia: Competition and Interactions Isabelle Charleux* Abstract This chapter investigates the architecture, icons, and activities of two Buddhist monasteries of the Old City of Hohhot, capital of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China: the (Tibeto-)Mongol Yeke juu (Ch. Dazhao[si]) and the Chinese Buddhist Guanyinsi. In it, I present a global view of the Buddhist revival of the Mongol monasteries of Hohhot since the 1980s, with a focus on the material culture—architecture, cult objects, and “decoration”—of the sites. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship. -

00. Introduction, Sudhana Cycle

SUDHANA CYCLE PREFACE When completed The Sudhana Cycle will consist of fifty-three “Works” with its inspiration, place of reference, and point of departure, being related in the Introduction below. At the time of its initiation the entire cycle was to be composed of either solos or duos. The original idea has transmogrified so as to become an open-ended concept, one I can no longer predict. Of the “Works” either written to date or thoroughly planned, instrumentation ranges from solos and trios through string quartet to a piece for double septet and trio. Compositional form is no longer limited by predetermination in any way. Though principles of structure and compositional procedure found firmly planted in the ground of Collective Autonomy are intrinsic to composition and performance practices as made manifest in the Sudhana Cycle, these are anything but dictates or matters of necessity. On the other hand though, they may well find themselves being strictly adhered to. While Collective Autonomy has a home in the Sudhana Cycle its deploy and behavior are not foregone conclusions nor are they to be taken for granted. Myself and my previous life’s work are in the service of the Sudhana Cycle and to feel free to say this is an absolute joy. Visiting the Sudhana Cycle page on this website you’ll find “Works” listed according to their Cycle No. The listings will run thus: No. 27 : Avalokite!vara - solo for alto flute; No. 24 : Sinhavijurmbhita - for solo violin, and so forth. There will be an entry in the Sudhana Cycle page Contents in accord with this numerical order and by clicking on the number you choose, information specific to that particular composition will appear. -

Sudhana's Pilgrimage for G3.Key

Buddhist Scripture as a Template for Maturation in Spiritual Cultivation A Presentation to Te Gethsemani IV Dialogue Gethsemani Abbey May 30, 2015 Rev. Heng Sure Venerable Master Hsuan Hua 1918-1995 Master Hsuan Hua was trained in the Tiantai tradition of scriptural exegesis He presented the voice of the Buddha in the sutras directly, unmediated by written commentaries, and accessible to contemporary, critical analysis. Master Hua critiqued the traditional Chinese conventions regarding the place and use of sutras as ritual objects as vehicles for merit-making as library cases & shelves as archaic philosophy Traditionally, practitioners, to relate to a sutra could: read and recite it memorize it copy it out reprint and distribute it bow to it decorate it translate it Sangha Members (and the occasional lay practitioner or scholar) could lecture on sutras, but rarely. Lecturing came with cautions: there were certain risks and conditions which by and large limited the number of sutras being lectured on, with the result that the value of sutras is largely unknown outside of Chinese Buddhist circles. Teir use was limited to reciting and ritual use. Te Buddha’s voice was seldom heard. Attitudes that limited lecturing on Mahayana Sutras: Exegesis is too dangerous. Explain one word incorrectly and you risk falling into the hells. Sutras are full of Sanskrit and difficult to read (so don’t lecture on them). Tis is the Dharma-ending Age, lecturing is wrong Attitudes towards lecturing Buddhist Sutras: (2) We lack the wisdom that the ancients had; we have to rely on their commentaries; the Buddha’s words aren’t accessible without commentary (so don’t lecture on them). -

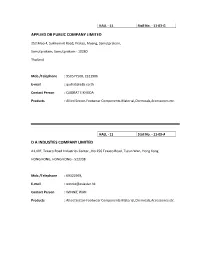

Applied Db Public Company Limited

HALL - 11 Stall No. - 11-03-G APPLIED DB PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED 252 Moo 4, Sukhumvit Road, Praksa, Muang, Samutprakarn, Samutprakarn, Samutprakarn - 10280 Thailand Mob./Telephone : 950577500, 2321906 E-mail : [email protected] Contact Person : QUDRAT E KHUDA Products : Allied Sector-Footwear Components-Material,Chemicals,Accessories etc. HALL - 11 Stall No. - 11-09-A D A INDUSTIES COMPANY LIMITED A1,10F, Texaco Road Industries Center,, No 256 Texaco Road, Tseun Wan, Hong Kong HONG KONG, HONG KONG - 523338 Mob./Telephone : 69322969, E-mail : [email protected] Contact Person : WINNIE WAN Products : Allied Sector-Footwear Components-Material,Chemicals,Accessories etc. HALL - 12A Stall No. - 12A-16-B DONGGUAN CHENGHUI INDUSTRIAL INVESTMENT CO.,LTD Kenglong Industrial Area, Nanya Village, Daojiao Town, Dongguan, Dongguan China Mob./Telephone : 86-13751311444, E-mail : [email protected] Contact Person : Mr.Han Products : Foam HALL - 12A Stall No. - 12A-10-D DONGGUAN HONGGUO LEATHER CO LTD NO.B312 NANFENG ,HETIAN,HOUJIE TWON, Dongguan, Dongguan - 523960 China Mob./Telephone : 86-13829207501, E-mail : [email protected] Contact Person : Ms.Elisa Meng Products : PU,PVC,TPU HALL - 12A Stall No. - 12A-09-A3 DONGGUAN HUICHUNG CORK PRODUCTS CO.,LTD No.6,Beiheng Rd2, Tingkeng Blvd,Tingshan,HoujieTown, Dongguan, Dongguan - 523943 China Mob./Telephone : 86-13825735666, E-mail : [email protected] Contact Person : Andy Liu Products : cork HALL - 12A Stall No. - 12A-10-E DONGGUAN KINGMING HARDWARE PLASTIC TECHNOLOGY CO.,LTD No. 196, Liaofu Road, Liaobu Town, Dongguan, Dongguan - 523425 China Mob./Telephone : 86-13066190336, E-mail : [email protected] Contact Person : Quan Zhou Products : Shoe Buckle,Boot Hooks,Crystal Rivet,Eyelet HALL - 12A Stall No. -

Emplacing Dizang Bodhisattva on Mt. Jiuhua with Local Dramas During the Late Imperial and Republican Eras (1368–1949)

Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies (2020, 33: 49–75) New Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institute of Buddhist Studies 中華佛學學報 第三十三期 頁 49–75(民國一百零九年)新北:中華佛學研究所 ISSN: 2313-2000 e-ISSN: 2313-2019 Emplacing Dizang Bodhisattva on Mt. Jiuhua with Local Dramas during the Late Imperial and Republican Eras (1368–1949) Nan Ouyang Postdoctoral Fellow, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore Abstract This article focuses on local dramas of late imperial China that speak to the conflation of Dizang Bodhisattva and Jin Dizang who is a prince-turned-monk from Silla and identified as the earthly incarnation of Dizang on Mt. Jiuhua. Drawing on local legends of Jin that evolved after the Tang period, the article selects four one-act plays that feature Jin to examine how local legends were adapted into the scripts by looking into the storylines, characters, language styles, and place-names associated with Mt. Jiuhua. It also investigates the similarities between these one-act plays and well-known acts of a typical Mulian drama, while taking into account the performative context of those plays in relation to the Dizang cult. It shows that the playwrights vigorously assimilated local religious dynamics in their creation of an onstage persona of Jin as an ascetic Buddhist monk. Lastly, the article discusses the distinctive strategies by which the four plays promoted the Dizang cult on Mt. Jiuhua, analyzes gender issues in the scripts, and further illustrates the dynamics between religion and performative literatures such as local drama. Keywords: local -

Fujian Tourism

© Lonely Planet Publications 331 Fújiàn 福建 Directly facing the island of Taiwan across the Taiwan Strait, the southern province of Fújiàn – famed for its fiendish tangle of tricky dialects – is a lushly mountainous, coastal region of China. Well watered and lashed by epic summer typhoons that sweep along the fertile coastline, the province is also renowned for an outward-looking mentality that has prompted centuries of migration to Malaysia, Singapore, the Philippines and Taiwan, and, FÚJIÀN in more recent years, a more covert movement to Europe and the US. One of China’s most prosperous provinces, Fújiàn’s coastal ports have long traded far and wide, but farmland is scarce and the mountainous interior remained inaccessible until as late as the 1960s, when the communists finally drove roads through the dense jungle. A popular route between Guǎngdōng, Zhèjiāng and Shànghǎi, Fújiàn offers one of the most diverse travel experiences in China. Rising like medieval forts, the astonishing Hakka tǔlóu (roundhouses) of Yǒngdìng County in Fújiàn’s southwest present a totally unique dimension to the China experience. One of China’s most attractive harbour cities and a useful first port of call, Xiàmén is a mandatory highlight along the coast. The hypnotically slow tempo, gorgeous colonial architecture, clean air and meandering, hilly lanes of offshore Gǔlàng Yǔ make the island an ideal place to unwind. The enclave is only a stone’s throw from the Taiwan-claimed island of Jīnmén (Kinmen), once the site of ferocious battles between mainland communists and the Nationalist Party. The province’s rugged mountainous dimension can be explored at Wǔyí Shān in the northwest, where excellent hiking opportunities await. -

9788825517057.Pdf

PROJECTS FOR : ANHAI a critical hypothesis for preservation and transformation Manuela Raitano Luca Reale PROJECTS «Projects For:» is a book series dedicated to architectural design in international FOR : contexts. Looking at our own way of practicing architecture through the lens of “difference” can help magnify its identity, pointing out its most relevant characters and providing an appropriate ground for critical thinking. Creating designs – or reflecting on projects – conceived for “elsewhere” can, in our opinion, become a powerful tool to understand how to make architecture. The series wants to provide a space dedicated to this critical activity, where the pretext of a specific lo- cation around the globe can serve as the center of gravity for design-oriented considerations. Series edited by Federico De Matteis Università degli Studi dell’Aquila, Italy Luca Reale Sapienza Università di Roma, Italy Editorial board Benno Albrecht IUAV Venezia, Italy Alessandra Capuano Sapienza Università di Roma, Italy Luciano Cardellicchio University of New South Wales, United Kingdom Giovanni Marco Chiri Università di Cagliari, Italy Jinyoung Chun Myongji University, Republic of Korea Josep-Maria Garcia-Fuentes University of Newcastle, United Kingdom Massimiliano Giberti Università di Genova, Italy Mazen Haidar Université Paris 1 - Panthéon Sorbonne, France Keya Mitra IIEST, Shibpur, India Luca Montuori Università Roma Tre, Italy Orsina Simona Pierini Politecnico di Milano, Italy Simona Salvo Sapienza Università di Roma, Italy Minghao Zhou Tongji University, Shanghai, P.R. China Graphic design Gina Oliva www.console-oliva.com Publisher © 2019 Aracne, Roma www.aracneeditrice.it [email protected] ISBN 978-88-255-1705-7 No part of this book can be reproduced without previous consent from the publisher. -

Zen Painting & Calligraphy

SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY 1223 02649 4907 amiEDUE [ SEPT 2 1997, 1I- —g—' 1» "> f ^ ' Bk Printed in USA . /30 CT - 8 1991 'painting £*- Calligraphy An exhibition of works of art lent by temples, private collectors, and public and private museums in Japan, organized in collaboration with the Agency for Cultural Affairs of the Japanese Government. Jan Fontein & Money L. Hickman of fine Arti, Boston Distributed by New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Connecticut Copyright © 1970 by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts All rights reserved ISBN 0-87846-001-2 Library of Congress Catalogue Card No. 76-127853 Typeset in Linofilm Palatino by Wrightson Typographers, Boston Printed by The Meriden Gravure Co., Meriden, Conn. Designed by Carl F. Zahn Dates of the Exhibition: November 5-December 20,1970 709-5,F737z Fontein, Jan Zen painting et v calligraphy Cover illustration: 20. "Red-Robed" Bodhidharma, artist, unknown, ca. 1271 Title page illustration: 48. Kanzan and Jittoku, traditionally attributed to Shubun (active second quarter of 15th century) (detail) S.F. PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1223 02649 4907 I Contents Foreword vii Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Chronology xii Introduction xiii The Beginnings of Ch'an Buddhism, xiii Chinese and Indian Thought in Ch'an Buddhism, xiv The Northern and Southern Schools, xvi The Earliest Form of Ch'an Art, xvi The Consolidation and Expansion of the Ch'an Sect, xvii Kuan-hsiu (832-912): The Birth of Ch'an Art, xix Ch'an Literature and Koan, xxi Ch'an Art during the Northern Sung Period (960-1126), XXII Ch'an -

Buddhanet.Net Web Site

Translated & Annotated under the Guidance of Dharma Master Hsuan Jung by Minh Thành & P.D. Leigh HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. D. T. Suzuki, Manual of Zen Buddhism (p. ): Yakushi (the Medicine Buddha) is the Bodhisattva doctor. He holds a medicine jar in his hand and is attended by twelve gods each of whom represents one of his twelve vows. Th e main object of his appearance among us is to cure us of ignorance, which is the most fundamental of all the ills the fl esh is heir to. May the merit and virtue accrued from this work adorn the Buddha’s Pure Land, repaying the four great kindnesses above, and relieve the suff ering of those on the three paths below. May those who see or hear of these eff orts generate Bodhi-mind, spend their lives devoted to the Buddha Dharma, and fi nally be reborn together in the Land of Ultimate Bliss. Homage to Amita Buddha! Taisho XIV, Translated and annotated under the guidance of Dharma Master Hsuan Jung By Minh Th anh & P.D. Leigh International Buddhist Monastic Institute Th e Sutra of the Medicine Buddha is among the most popular texts in East Asia, along with the Amitabha, the Ksitigarbha and the Lotus sutras. Th is new translation, freely available to all seekers, includes the oral comments of several contemporary senior monks. Second edition International Buddhist Monastic Institute Columbus Avenue North Hills, CA (USA) tel. -

Phagpa Lokes'vara of the Potala Ian Alsopkathmandu

Asianart.com | Articles Asianart.com offers pdf versions of some articles for the convenience of our visitors and readers. These files should be printed for personal use only. Note that when you view the pdf on your computer in Adobe reader, the links to main image pages will be active: if clicked, the linked page will open in your browser if you are online. This article can be viewed online at: http://asianart.com/articles/phagpa Pagpawati Jowo's Rescue Story Excerpt from Chapter 6 of G. Childs' The Rising Mist Phagpa Lokes'vara of the Potala Ian AlsopKathmandu December 14, 1999 originally published in Orientations, April 1990 _______________________________________________________ In The Newark Museum collection is a small ivory figure representing a form of Avalokites'vara of a type that has long puzzled historians of Himalayan art (Fig. 1). Figures displaying the stylistic eccentricities of this bodhisattva are, as evidenced here, relatively common. These stylistic eccentricities can be briefly catalogued as: a high three-lobed crown of rather simple design; the hair in an elaborate chignon which spills in two long buns on either side of the head and crown, and bell-like earrings. The images also show a remarkable lack of ornamentation; they stand on a small, square base in a relatively stiff pose, with, when complete, the right hand in varada mudra (gesture of bestowal) and the left close to the thigh in a gesture of holding a (missing) lotus. Figures of this distinctive type can be found in many private and museum collections and almost every broad-based collection Fig. -

Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports and Early Maritime Globalization the Archaeology of Asia-Pacific Navigation

The Archaeology of Asia-Pacific Navigation 2 Chunming Wu Roberto Junco Sanchez Miao Liu Editors Archaeology of Manila Galleon Seaports and Early Maritime Globalization The Archaeology of Asia-Pacific Navigation Volume 2 Series Editor Chunming Wu, The Center for Maritime Archaeology, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China This series will publish the most important, current archaeological research on ancient navigation and sea routes in the Asia-Pacific region, which were key, dynamic factors in the development of human civilizations spanning the last several thousand years. Restoring an international and multidisciplinary academic dialogue through cross cultural perspectives, these publications underscore the significance of diverse lines of evidence, including sea routes, ship cargo, shipwreck, seaports landscape, maritime heritage, nautical technology and the role of indigenous peoples. They explore a broad range of outstanding work to highlight various aspects of the historical Four Oceans sailing routes in Asia-Pacific navigation, as well as their prehistoric antecedents, offering a challenging but highly distinctive contribution to a better understanding of global maritime history. The series is intended for scholars and students in the fields of archaeology, history, anthropology, ethnology, economics, sociology, and political science, as well as nautical technicians and oceanic scientists who are interested in the prehistoric and historical seascape and marine livelihood, navigation and nautical techniques, the maritime silk road and overseas trade, maritime cultural dissemination and oceanic immigration in eastern and southeastern Asia and the Pacific region. The Archaeology of Asia-Pacific Navigation book series is published in conjunction with Springer under the auspices of the Center for Maritime Archaeology of Xiamen University (CMAXMU) in China.