Privateers of Skagerrak LICENSED to PLUNDER Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stakeholder Involvement Work Package 8

Stakeholder Involvement Work Package 8 European Union European Regional Development Fund Kop 2 Fife Coast and Countryside Trust was responsible for the coordination of Work Package 8: “Stakeholder Involvement”. This report was prepared by Julian T. Inglis, Fulcrum Environmental Management, on behalf of the Trust. The thoughts and opinions expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Trust or other partners in the SUSCOD project. The author is solely responsible for the accuracy of the information contained in the report. Please send your comments to [email protected] Table of Contents Summary 6 Section 1: Introduction to stakeholder involvement in the SUSCOD project .........................................8 Section 2: Process for developing the final report on stakeholder involvement .............................. 11 Section 3: A typology of the main categories of stakeholder involvement .......................................... 14 a. Partnerships ............................................................................................................................................................. 15 (i) Coastal Partnerships ............................................................................................................................................... 15 Coastal partnerships in Scotland ............................................................................................................... 16 Coastal Partnerships and emerging marine planning partnerships -

The Dark Unknown History

Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century Ds 2014:8 The Dark Unknown History White Paper on Abuses and Rights Violations Against Roma in the 20th Century 2 Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry Publications Series (Ds) can be purchased from Fritzes' customer service. Fritzes Offentliga Publikationer are responsible for distributing copies of Swedish Government Official Reports (SOU) and Ministry publications series (Ds) for referral purposes when commissioned to do so by the Government Offices' Office for Administrative Affairs. Address for orders: Fritzes customer service 106 47 Stockholm Fax orders to: +46 (0)8-598 191 91 Order by phone: +46 (0)8-598 191 90 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.fritzes.se Svara på remiss – hur och varför. [Respond to a proposal referred for consideration – how and why.] Prime Minister's Office (SB PM 2003:2, revised 02/05/2009) – A small booklet that makes it easier for those who have to respond to a proposal referred for consideration. The booklet is free and can be downloaded or ordered from http://www.regeringen.se/ (only available in Swedish) Cover: Blomquist Annonsbyrå AB. Printed by Elanders Sverige AB Stockholm 2015 ISBN 978-91-38-24266-7 ISSN 0284-6012 3 Preface In March 2014, the then Minister for Integration Erik Ullenhag presented a White Paper entitled ‘The Dark Unknown History’. It describes an important part of Swedish history that had previously been little known. The White Paper has been very well received. Both Roma people and the majority population have shown great interest in it, as have public bodies, central government agencies and local authorities. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Invasions, Insurgency and Interventions: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark 1654 - 1658. A Dissertation Presented by Christopher Adam Gennari to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christopher Adam Gennari 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christopher Adam Gennari We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Ian Roxborough – Dissertation Advisor, Professor, Department of Sociology. Michael Barnhart - Chairperson of Defense, Distinguished Teaching Professor, Department of History. Gary Marker, Professor, Department of History. Alix Cooper, Associate Professor, Department of History. Daniel Levy, Department of Sociology, SUNY Stony Brook. This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School """"""""" """"""""""Lawrence Martin "" """""""Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Invasions, Insurgency and Intervention: Sweden’s Wars in Poland, Prussia and Denmark. by Christopher Adam Gennari Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 "In 1655 Sweden was the premier military power in northern Europe. When Sweden invaded Poland, in June 1655, it went to war with an army which reflected not only the state’s military and cultural strengths but also its fiscal weaknesses. During 1655 the Swedes won great successes in Poland and captured most of the country. But a series of military decisions transformed the Swedish army from a concentrated, combined-arms force into a mobile but widely dispersed force. -

Landskapsanalys.Pdf

Landskapsanalys Vindbruk - tematiskt tillägg till Översiktsplanen, Lysekils kommun Antagandehandling 2012-05-18 Dnr: LKS 10-4-375 Vindbruk - tematiskt tillägg till översiktsplanen. Beställare: Lysekil kommun Konsult: Vectura Planchef: Josefin Kaldo, Lysekils kommun Uppdragsledare: Lena Lundkvist, Vectura Landskapsarkitekter: Ann Henrikson och Sara Tärk, Vectura GIS och kartor: Anders Ala-Häivälä och Ola Rosenqvist, Vectura Foton tagna av Vectura. Framsida: Vindkraftverket Elvira i Lysekils kommun. 2 Landskapsanalys Innehåll Metod 5 Landskapskaraktärsanalys 5 Landskapets förutsättningar 5 Naturgeografiska strukturer 6 Kulturgeografiska strukturer 8 Sociala strukturer 10 Naturvärden och ekologiska samband 10 Landskapskaraktärer 13 1. Kust och skärgård 14 2. Kala höjdplatåer 15 3. Mosaiklandskap 16 4. Fjordlandskap 17 5. Delvis skogiga höjdplatåer 18 Slutsatser 19 Källor 20 3 Vindbruk - tematiskt tillägg till översiktsplanen. DINGLE MUNKEDALS KOMMUN BOVALLSTRAND MUNKEDAL ULEBERGSHAMN F ä r TORREBY l HUNNEBOSTRAND e v f j o r d e n BRODALEN BARKEDAL GÅRVIK SOTENÄS KOMMUN s ä s n ä e n t r n e ä So d VÄJERN r H BRASTAD o fj Fågelviken y b HOVENÄSET Å RIXÖ Brofjorden BÖRSÅS KUNGSHAMN s PREEMRAFF ä MALMÖN n rn e a g m n ll å u G St KOLVIK KRISTEVIK KOLLERÖD UDDEVALLA KOMMUN s nä LYSEKIL ke Bo KAVLANDA GÅRE LYSEKILS KOMMUN RÖRBÄCK FISKEBÄCKSKIL SÖDRA MUNKEBY - t HENÅN ftö e a nd Sk la GRUNDSUND Islandsberg ORUSTS KOMMUN Jonsborg ELLÖS 0 2 4 6 km © Lantmäteriet MS2009/09632 Karta 1. Översikt över Lysekils kommun 4 Landskapsanalys Metod Landskapskaraktärsanalys I denna landskapsanalys har metoden landskapskaraktärsanalys använts. Kommunens yta har analyserats med avseende på natur, kultur och upplevelse. Vid en analys av land- skapskaraktärer undersöks och beskrivs olika områdens platskänsla och skillnaderna mellan dessa. -

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania

A Short History of Poland and Lithuania Chapter 1. The Origin of the Polish Nation.................................3 Chapter 2. The Piast Dynasty...................................................4 Chapter 3. Lithuania until the Union with Poland.........................7 Chapter 4. The Personal Union of Poland and Lithuania under the Jagiellon Dynasty. ..................................................8 Chapter 5. The Full Union of Poland and Lithuania. ................... 11 Chapter 6. The Decline of Poland-Lithuania.............................. 13 Chapter 7. The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania : The Napoleonic Interlude............................................................. 16 Chapter 8. Divided Poland-Lithuania in the 19th Century. .......... 18 Chapter 9. The Early 20th Century : The First World War and The Revival of Poland and Lithuania. ............................. 21 Chapter 10. Independent Poland and Lithuania between the bTwo World Wars.......................................................... 25 Chapter 11. The Second World War. ......................................... 28 Appendix. Some Population Statistics..................................... 33 Map 1: Early Times ......................................................... 35 Map 2: Poland Lithuania in the 15th Century........................ 36 Map 3: The Partitions of Poland-Lithuania ........................... 38 Map 4: Modern North-east Europe ..................................... 40 1 Foreword. Poland and Lithuania have been linked together in this history because -

Annual Report 2017

Rabbalshede Kraft Annual Report 2017 WE ALWAYS FIND POWER IN THE WIND CONTENTS About Rabbalshede Kraft 3 Vision, business concept, target 3 2017 in brief 4 Performance during the year 5 CEO’s statement 6 Operations in 2017 8 Focus growth and sales 9 History 10 Wind farms under operation and development 12 Four questions to our main sharholders 14 Establishing wind farms 16 The Market 18 Wind Power 18 The electricity market 20 Electricity certificates 23 Rabbalshede Kraft's share 24 Board of Directors 26 Senior executives 27 Administration report and financial statements Multi-year review 30 Administration report 31 Consolidated income statement 36 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 36 Consolidated balance sheet 37 Consolidated statement of changes in shareholders’ equity 38 Consolidated cash-flow statement 39 Parent Company income statement 40 Parent Company’s statement of comprehensive income 40 Parent Company balance sheet 41 Changes in Parent Company’s shareholders’ equity 43 Parent Company cash-flow statement 44 Notes to the financial statements 45 Auditors’ Report 74 2 ABOUT RABBALSHEDE KRAFT RABBALSHEDE KRAFT ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Rabbalshede Kraft in brief Rabbalshede Kraft makes a difference. ments in addition to the obvious aspect of In the move toward sustainable development, producing electricity. it is important that society increases the per- centage of electricity derived from renewable Rabbalshede Kraft offers investors and energy sources, one such energy source is wind power owners a comprehensive wind. Rabbalshede Kraft is a leading compa- operational management solution. ny in wind power in Sweden. From the com- A professional service organisation, in close pany’s founding in 2005 up until December cooperation with the suppliers of the 2017, Rabbalshede Kraft has invested nearly turbines, contributes to high operational SEK 2.6 billion in wind power. -

Connecting Øresund Kattegat Skagerrak Cooperation Projects in Interreg IV A

ConneCting Øresund Kattegat SkagerraK Cooperation projeCts in interreg iV a 1 CONTeNT INTRODUCTION 3 PROgRamme aRea 4 PROgRamme PRIORITIes 5 NUmbeR Of PROjeCTs aPPROveD 6 PROjeCT aReas 6 fINaNCIal OveRvIew 7 maRITIme IssUes 8 HealTH CaRe IssUes 10 INfRasTRUCTURe, TRaNsPORT aND PlaNNINg 12 bUsINess DevelOPmeNT aND eNTRePReNeURsHIP 14 TOURIsm aND bRaNDINg 16 safeTy IssUes 18 skIlls aND labOUR maRkeT 20 PROjeCT lIsT 22 CONTaCT INfORmaTION 34 2 INTRODUCTION a short story about the programme With this brochure we want to give you some highlights We have furthermore gathered a list of all our 59 approved from the Interreg IV A Oresund–Kattegat–Skagerrak pro- full-scale projects to date. From this list you can see that gramme, a programme involving Sweden, Denmark and the projects cover a variety of topics, involve many actors Norway. The aim with this programme is to encourage and and plan to develop a range of solutions and models to ben- support cross-border co-operation in the southwestern efit the Oresund–Kattegat–Skagerrak area. part of Scandinavia. The programme area shares many of The brochure is developed by the joint technical secre- the same problems and challenges. By working together tariat. The brochure covers a period from March 2008 to and exchanging knowledge and experiences a sustainable June 2010. and balanced future will be secured for the whole region. It is our hope that the brochure shows the diversity in Funding from the European Regional Development Fund the project portfolio as well as the possibilities of cross- is one of the important means to enhance this development border cooperation within the framework of an EU-pro- and to encourage partners to work across the border. -

Swedish Coastal Zone Management a System for Integration of Various Activities

· , In'fernational Council C.M. 19941F10, Ref. E. for the Exploration of the 5ea Mariculture Committee / SWEDISH COASTAL ZONE MANAGEMENT A SYSTEM FOR INTEGRATION OF VARIOUS ACTIVITIES SY HANS ACKEFORS' AND KJELL GRlp2 5tockholm University 5wedish Environmental Department of Zoology Protection Agency 5-106 91 5TOCKHOLM Research Department 5weden 5-171 85 50LNA 5weden 1 Table of contents O. Abstract 1. INTRODUCTION 2. MULTIPLE USES OF THE COASTAL ZONE 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Aquaculture 2.3 Leisure life 2.4 Fisheries 2.5 Shipping 2.6 Mineral and oil exploitation 2.7 Military establishment and activities 2.8 Industries 2.9 Coastal zone as a recipient 2.10 Cables and pipelines 2.11 Energy from the sea 3. SWEDISH INSTITUTIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND LAW SYSTEMS 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Legal framework 3.3 Monitoring 3.4 Research 3.5 Basic strategies for protecting the environment Eutrophication Persistent organic pollutants 4. EXAMPLES HOW SWEDISH LEGISLATION IS APPLIED 4.1 Aquaculture 4.2 Building of a bridge between Sweden and Denmark 5. THE PLANNING OF A COASTAL MUNICIPALITY e 5.1 Lysekil municipality . 5.2 The national interests of Lysekil municipality 5.3 Activities and interests and coherent conflicts and competition 5.4 The present status of the environment 5.5 The main characteristics of the comprehensive physical plan 5.5.1 Areas with provisions and special regulations which are under examination of the County Administrative Board 5.5.2 Recommendations for the use of water areas 5.5.3 Recommendations for discharges of water and new buildings 5.5.4 Measures to alleviate the impact on the sea environment 5.5.5 A plan for the use of water resources and treatment plants 2 6. -

Lusardi 1999- Blackbeard Shipwreck Project with a Note on Unloading A

The Blackbeard Shipwreck Project, 1999: With a Note on Unloading a Cannon By: Wayne R. Lusardi NC Underwater Archaeological Conservation Laboratory Institute of Marine Sciences 3431 Arendell Street Morehead City, North Carolina 28557 Lusardi ii Table of Contents Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 1999 Field Season.................................................................................................................................1 Figure 1: Two small cast-iron cannons during removal of concretion and associated ballast stones. ...................................................................................................................................1 The Artifacts .........................................................................................................................................2 Ship Parts and Equipment...................................................................................................................2 Arms...................................................................................................................................................2 Figure 2: Weight marks on breech of cannon C-21..............................................................3 Figure 3: Contents of cannon C-19 included three iron drift pins, a solid round shot and three wads of cordage.........................................................................................................3 -

From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University

Civility at Sea: From Murmuring to Mutiny Bruce Buchan School of Humanities, Languages and Social Sciences Griffith University n 1749 the articles of war that regulated life aboard His Britannic Majesty’s I vessels stipulated: If any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous Assembly upon any Pretense whatsoever, every Person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the Sentence of the Court Martial, shall suffer Death: and if any Person in or belong- ing to the Fleet shall utter any Words of Sedition or Mutiny, he shall suffer Death, or such other Punishment as a Court Martial shall deem him to deserve. [Moreover] if any Person in or belonging to the Fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous Words spoken by any, to the Prejudice of His Majesty or Government, or any Words, Practice or Design tending to the Hindrance of the Service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the Commanding Officer; or being present at any Mutiny or Sedition, shall not use his utmost Endeavors to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a Court Martial shall think he deserves.1 These stern edicts inform a common image of the cowed life of ordinary sailors aboard vessels of the Royal Navy during its golden age, an image affirmed by the testimony of Jack Nastyface (also known as William Robinson, 1787–ca. 1836), for whom the sailor’s lot involved enforced silence under threat of barbarous and tyrannical punishment.2 In the soundscape of maritime life 1 Articles 19 and 20 of An Act for Amending, Explaining and Reducing into One Act of Parliament, the Laws Relating to the Government of His Majesty’s Ships, Vessels and Forces by Sea (also known as the 1749 Naval Act or the Articles of War), 22 Geo. -

PIRATES Ssfix.Qxd

E IFF RE D N 52 T DISCOVERDISCOVER FAMOUS PIRATES B P LAC P A KBEARD A IIRRAATT Edward Teach, E E ♠ E F R better known as Top Quality PlayingPlaying CardsCards IF E ♠ SS N Plastic Coated D Blackbeard, was T one of the most feared and famous 52 pirates that operated Superior Print along the Caribbean and A Quality PIR Atlantic coasts from ATE TR 1717-18. Blackbeard ♦ EAS was most infamous for U RE his frightening appear- ance. He was huge man with wild bloodshot eyes, and a mass of tangled A hair and beard that was twisted into dreadlocks, black ribbons. In battle, he made himself andeven thenmore boundfearsome with by ♦ wearing smoldering cannon fuses stuffed under his hat, creating black smoke wafting about his head. During raids, Blackbeard car- ried his cutlass between his teeth as he scaled the side of a The lure of treasure was the driving force behind all the ship. He was hunted down by a British Navy crew risks taken by Pirates. It was ♠ at Ocracoke Inlet in 1718. possible to acquire more booty Blackbeard fought a furious battle, and was slain ♠ in a single raid than a man or jewelry. It was small, light, only after receiving over 20 cutlass wounds, and could earn in a lifetime of regu- and easy to carry and was A five pistol shots. lar work. In 1693, Thomas widely accepted as currency. A Tew once plundered a ship in Other spoils were more WALKING THE PLANK the Indian Ocean where each practical: tobacco, weapons, food, alco- member received 3000 hol, and the all important doc- K K ♦ English pounds, equal to tor’s medical chest. -

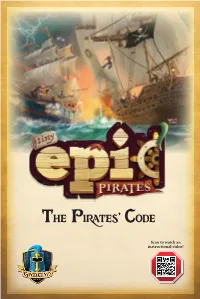

The Pirates' Code

The Pirates’ Code Scan to watch an instructional video! Components Legend Legend Legend Dread Legend Dread Dread Pirate Sure-fire Dread Pirate Sure-fire Pirate Sure-fire Pirate - Buccaneer Sure fire Buccaneer Buccaneer Buccaneer Swash 1 Market Mat Swash Buckler Swash Buckler Swash Buckler Buckler Corsair Corsair Corsair Corsair Pirate Pirate Pirate Pirate Sea Dog Sea Dog Sea Dog Repair Sea Dog Repair Repair Extort Repair Extort : Extort Cannons: Extort Cannons: Cannons: Rigging 1 Cannons Rigging 1 Rigging 1 1 Rigging 1 1 2 Port Tokens 1 1 4 Legend Mats 4 Helm Mats 16 Map Cards 8 8 6 6 6 4 4 4 2 2 2 1-4 1-4 1-3 1-3 1-3 1-2 1-2 1-2 . Cpt. Carmen RougeCpt Morgan Whitecloud FRONTS . Francisco de Guerra Cpt. Magnus BoltCpt BACKS 11 Merchant Cards 4 Double-Sided Captain Cards Alice O’Malice 1 Doc Blockley Lisa Legacy Sydney Sweetwater Buck Cannon Betty Blunderbuss Eliza Lucky Ursula Bane Willow Watch Taylor Truenorth Quartermaster Quigley Jolly Rodge Silent Seamus Lieutenant Flint Raina Rumor Black-Eyed Brutus Pale Pim 2 Salty Pete 2 Cutter Fang BACKS Sara Silver Jack “Fuse” Rogers Chopper Donovan Sally Suresight FRONTS Tina Trickshot 24 Crew Cards BACKS BACKS FRONTS 20 Search Tokens FRONTS 20 Order Tokens (5 in 4 colors) 2 4 Pirate Ships (in 4 colors) 2 Merchant Ships (in 2 colors) 1 Navy Ship 4 Captains (in 4 colors) 16 Deckhands 4 Legend Tokens 12 Treasures (4 in 4 colors) (in 4 colors) (3 in 4 colors) 1 Booty Bag 40 Booty Crates 4 Gold 3 Dice 12 Sure-fire Tokens (10 in 4 colors) Doubloons Prologue You helm a notorious pirate ship in the swashbuckling days of yore.