20Th-Century Tuba Concertos Øystein Baadsvik

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

02.12.14 Symphony FINAL.Indd

UPCOMING EVENTS Symphonic Band Concert With CSU Faculty Peter Sommer, Saxophone & Special Guest Joel Puckett, Composer-in-Residence 2/20 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 p.m. UNIVERSITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Wind Ensemble Concert CONCERTO COMPETITION FINALS With Special Guest John Lynch, Conductor Star Search Comes to CSU 2/21 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 p.m. Wes Kenney, Conductor CSU Honor Band Concert With Special Guest John Lynch, Conductor CA 2/22 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 p.m. PROGRAM Virtuoso Series Concert Alexander Arutiunian Trumpet Concerto in A-flat Major CSU Faculty Tiffany Blake, Soprano & John Seesholtz, Baritone With Dr. Annie McDonald, Piano (1920-2012) (1950) 2/24 • Organ Recital Hall • 7:30 p.m. Soloist: Robert Bonner Virtuoso Series Concert nniversary With Special Guests Christine Rutledge, Viola & David Gompper, Piano Julius Conus Violin Concerto in E Minor (1869-1942) (1896) 2/25 • Organ Recital Hall • 7:30 p.m. A Soloist: Adrián Barrera Ramos event calendar • e-newsletter registration Sergei Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 www.uca.colostate.edu (1891-1953) (1921) I. Andante-Allegro 5th General information: (970) 491-5529 Soloist: Yolanda Tapia Hernandez Tickets: (970) 491-ARTS (2787) Meet Me at the UCA Season “Green” Sponsor www.CSUArtsTickets.com the U e at INTERMISSION Thank you for your continued support Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 5 in E minor M (1840-1893) (1888) I. Andante-Allegro con anima II. Andante Cantabile con alcuna licenza III. Valse. Allegro moderato IV. Finale. Andante maestoso-Allegro vivace eet Wednesday, February 12, 2014 M Griffin Concert Hall, University Center for the Arts PROGRAM NOTES Friends of the UCA at Colorado State University Trumpet Concerto Alexander Arutiunian connects you to students and faculty who inspire, teach, and heal at Colorado State. -

Sharing Christmas Joy in Armenia and Artsakh

AMYRIGA#I HA# AVYDARAN{AGAN UNGYRAGXOV:IVN ARMENIAN MISSIONARY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA AMAA NEWS LI 1 Sharing Christmas Joy in Jan-Feb-March 2017 Armenia and Artsakh P. 11 CONTENTS January•February•March 2017 /// LI1 3 Editorial Against the Tide By Zaven Khanjian 4 Inspirational Corner A Resurrection Reflection By Rev. Haig Kherlopian 1918 2018 5 Around the Globe Armenian Evangelical Church of New York By Peter Kougasian, Esq. 6 Almost a Hundred Years Later By Heather Ohaneson, Ph.D. 7 In Memoriam: Samuel Chekijian 8 Meet Our Veteran Pastors Rev. Dr. Joseph Alexanian AMAA NEWS 9 Remembering Hrant Dink By Zaven Khanjian is a publication of 10 Stitched With Love By Betty Cherkezian The Armenian Missionary Association of America 11 AMAA Shares Christmas Joy with Children in Armenia and Karabagh 31 West Century Road, Paramus, NJ 07652 Tel: (201) 265-2607; Fax: (201) 265-6015 12 AMAA's Humanitarian Aid to the Armenian Army E-mail: [email protected] 13 Armenian Children's Milk Fund Website: www.amaa.org (ISSN 1097-0924) 14 A Time of Ending and Sending By Jeannette Keshishian 15 New Missionaries Go Into the World to Preach, To Serve By Zaven Khanjian The AMAA is a tax-exempt, not for profit 17 God's Faithfulness By Nanor Kelenjian Akbasharian organization under IRS Code Section 501(c)(3) 18 Relief is Still Needed in Syria Zaven Khanjian, Executive Director/CEO 19 AMAA's Syria LifeLine Relocates 113 Families to the Homeland Levon Filian, West Coast Executive Director David Aynejian, Director of Finance 20 First Armenian Evangelical Church of Montreal -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

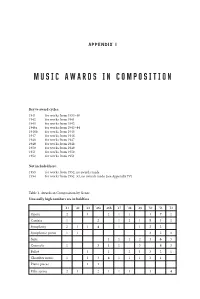

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

The History and Usage of the Tuba in Russia

The History and Usage of the Tuba in Russia D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James Matthew Green, B.A., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Document Committee: Professor James Akins, Advisor Professor Joseph Duchi Dr. Margarita Mazo Professor Bruce Henniss ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright by James Matthew Green 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract Beginning with Mikhail Glinka, the tuba has played an important role in Russian music. The generous use of tuba by Russian composers, the pedagogical works of Blazhevich, and the solo works by Lebedev have familiarized tubists with the instrument’s significance in Russia. However, the lack of available information due to restrictions imposed by the Soviet Union has made research on the tuba’s history in Russia limited. The availability of new documents has made it possible to trace the history of the tuba in Russia. The works of several composers and their use of the tuba are examined, along with important pedagogical materials written by Russian teachers. ii Dedicated to my wife, Jillian Green iii Acknowledgments There are many people whose help and expertise was invaluable to the completion of this document. I would like to thank my advisor, professor Jim Akins for helping me grow as a musician, teacher, and person. I would like to thank my committee, professors Joe Duchi, Bruce Henniss, and Dr. Margarita Mazo for their encouragement, advice, and flexibility that helped me immensely during this degree. I am indebted to my wife, Jillian Green, for her persistence for me to finish this document and degree. -

BAMBER in Cooperation with University of the Pacific Conservatory Ofmusic Fifty-First Season Stockton, California Program

STRATA fRIEND~ Of Nathan Williams, clarinet James Stern, violin/ viola Audrey Andrist,piano 2:30 PM, December 3, 2006 U~I Faye Spanos Concert Hall BAMBER In cooperation with University of the Pacific Conservatory ofMusic Fifty-First Season Stockton, California Program Trio Sonata in G Major for Clarinet, Violin & Piano (after BWVI039) J. S. BACH Adagio (1685-1750) Allegro rna non presto Adagio e piano Presto From E£ght Pieces for Clarinet, Viola and Piano, Ope 83 Max BRUCH II: Allegro can mota (1838-1920) VII: Allegro vivace, rna non troppo VI: Nachtgesang (Andante can mota) IV: Allegro agitato -intermission- Little Concerto for Clarinet, Viola and Piano (1937) Alfred UHL Allegro can brio (1909-1992) Grave Vivo Suite for Clarinet, Violin and Piano (1992) Alexander ARUTIUNIAN Introduction (b. 1920) Scherzo Dialog Final Strata is represented byLois Scott Management, Inc., P.O. Box 140, Closter, NJ 07624 www.loisscottmanagement.com The Artists Canadian pianist Audrey Andrist is When Bach used this format, he The musicians of STRATA, old the 1994 first prize winner of the San wrote the triosonata for two treble Antonio International Keyboard instruments accompanied by a basso friends to many in Stockton, have been Competition and was presented in a performing and appearing in concert continuo, usually a keyboard plus cross-Canada solo recital tour as either cello or bassoon. The sonata together since 1988. All three hold the winner of the Eckhardt-Gramatte da chiesa (church sonata) format in Doctor ofMusical Arts degree from the Competition. She has appeared as which this piece is written comprises Juilliard School, where their first soloist with the National Arts Centre an instrumental ensemble in four performances as an ensemble Orchestra in Ottawa, the Juilliard movements alternating in two slow occurred. -

Exploring Armenian Keyboard Music : Roots to Modern Times Marina Berberian Florida International University

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-20-2010 Exploring Armenian keyboard music : roots to modern times Marina Berberian Florida International University DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14051105 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Berberian, Marina, "Exploring Armenian keyboard music : roots to modern times" (2010). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1604. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1604 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida EXPLORING ARMENIAN KEYBOARD MUSIC: ROOTS TO MODERN TIMES A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by Marina Berberian 2010 To: Acting Dean Brian Schriner College of Architecture and the Arts This thesis, written by Marina Berberian, and entitled Exploring Armenian Keyboard Music: Roots to Modern Times, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. Joel Galand Jose Lopez Kemal Gekic, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 20, 2010 The thesis of Marina Berberian is approved. Acting Dean -

Comparison Between J

Comparison between J. Haydn Trumpet Concerto in Eb and A. Arutiunian Trumpet Concerto in Ab By Neil Davidson Harrogate Grammar School Music A level project 1999 Contents Exposition of Aims History of the Haydn and Arutiunian Trumpet Concertos Joseph Haydn Alexander Arutiunian Rhythm Melody Texture / Timbre Form Conclusion Bibliography Appendices Timofei Dokshizer Interview with Arutiunian Comparison of the instruments of each orchestra The Keyed Eb Trumpet Russian Influences Programme Notes (HSO) 2 Exposition of Aims I have chosen to explore the two trumpet concerti by Joseph Haydn and Alexander Arutiunian because having played the trumpet for over nine years now I have discovered a particular interest in Russian brass music. I have seen John Wallace play the Arutiunian Trumpet concerto, accompanied by the Williams Fairey Brass Band in an arrangement by Roger Harvey at the Bridgewater Hall in Manchester last year. However, the Haydn trumpet concerto was my introduction to brass concertos and it was the first concerto I performed (2nd movement in 1998). I also intend to play the Arutiunian concerto for my A-level practical examination. The Haydn trumpet concerto is the most famous trumpet concerto written and is Haydn’s most well known concerto for any instrument so it serves as benchmark to contrast against the relatively modern and obscure Arutiunian concerto. I have studied Russian music as part of the Music A-level history syllabus and I enjoy the music of Oskar Bohme, Alexander Goedicke, Vassily Brandt, Alexandria Pakhmutova, and of course, Alexander Arutiunian. These are all Russian composers who made a significant contribution to the solo trumpet repertoire in the twentieth century. -

TRUMPET RENAISSANCE Includes Premiere Recordings Concertos by Birtwistle • Jost • Roger • Arutiunian

CHAN 10562 CHAN 10552 TRUMPET RENAISSANCE includes premiere recordings Concertos by Birtwistle • Jost • Roger • Arutiunian Philippe Schartz trumpet BBC National Orchestra of Wales Jac van Steen Trumpet Renaissance Sir Harrison Birtwistle (b. 1934) 1 Endless Parade (1986 –87) 18:02 for Trumpet, Strings and Vibraphone Commissioned by Paul Sacher for Håkan Hardenberger and the Collegium Musicum Chris Stock vibraphone Christian Jost (b. 1963) Photograph by Mykel Nicolaou © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library premiere recording Pietà (2004) 22:45 in memoriam Chet Baker Concerto for Trumpet in B flat and Orchestra 2 = 63, gleichmäßig ruhig, nicht eilen – 7:06 3 [ ] – 3:24 4 [ ] – 3:42 5 [ ] 8:33 Sir Harrison Birtwistle, 2003 3 Trumpet Renaissance Kurt Roger (1895 –1966) The natural trumpet of the baroque period, and Arnold Schoenberg. He taught at the premiere recording with its specialist high-register technique, Vienna Conservatory from 1923 to 1938, Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op. 27 (1936) 15:50 played a significant role in the birth and when he was forced by the Nazi Anschluss for Solo Trumpet, Timpani and String Orchestra development of the concerto; and around to emigrate. He went via London to the 1800 the classic concertos of Haydn and United States, of which he became a citizen 6 1 Animato, ma pesante 4:40 Hummel were written to show off the short- in 1945. He held teaching posts in New York 7 2 Adagio, molto sostenuto ed espressivo – 6:29 lived keyed trumpet. But the invention of and Washington, D.C., and his music was the modern valve trumpet did not lead to performed by several leading American 8 3 Con brio 4:35 a flood of concertos by major composers: orchestras. -

MUSIC from Armeniafor Cello and Piano

MUSIC FROM ARMENIA for Cello and Piano Heather Tuach, cello Patil Harboyan, piano Alexander Arutiunian (1920-2012) 1. Impromptu 4.27 Gomidas (1869-1935) 2. Groung – arr. Aslamazian 3.51 Arno Babajanian (1921-1983) 3. Vocalise – arr. Talalyan 3.09 Haro Stepanian (1897-1966) Sonata for Cello and Piano, Op. 35 4. I. Allegro risoluto 10.49 5. II. Andante cantabile 4.33 6. III.Allegretto giocoso 6.39 Gomidas (1869-1935) 7. Karoun A (It’s Spring) – arr. Andreasian/Talalyan 2.54 8. Keler Tsoler (Striding, Beaming) – arr. Aslamazian/Talalyan 2.51 9. Chinar Es (Tall Like a Poplar Tree) – arr. Aslamazian/Talalyan 2.14 10. Dzirani Dzar (Apricot Tree) – arr.Talalyan 2.37 11. Shoushigi (Dance of Shoushig) – arr. Aslamazian/Talalyan 2.05 12. Kele Kele (Strolling) – arr. Aslamazian/Talalyan 1.39 13. Akh Maral Jan (Ah, Dear Maral) – arr. Talalyan 3.19 14. Yerginkn Ambel A (The Sky Has Clouded) – arr. Aslamazian/Talalyan 1.47 15. Shogher Jan (Dear Shogher) – arr. Aslamazian/Talalyan 3.11 Total CD duration 56.52 THE MUSIC NOTES IN ENGLISH, ARMENIAN AND FRENCH The idea of recording MUSIC FROM ARMENIA FOR CELLO AND PIANO began in 2012, following a recital in Heather Tuach’s home province of Newfoundland where she and Patil Harboyan performed Arutiunian’s Impromptu for the first time. It proved to be a huge hit with the audience. Spurred on by this, the duo started investigating the Armenian cello and piano repertoire to see what might be compiled onto a CD that would be accessible and appealing to a wide range of listeners. -

Advance Program Notes Chamber Music Series June 13-29, 2016

Advance Program Notes Chamber Music Series June 13-29, 2016 These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Chamber Music Series June 13-29, 2016 All performances are free and will be held in the Anne and Ellen Fife Theatre, Street and Davis Performance Hall in the Moss Arts Center unless otherwise noted. Thursday, June 16, 2016, 7:30 PM Saturday, June 25, 2016, 7:30 PM SUMMER NIGHTS AND MELODIES FOLK INSPIRATIONS AND ECHOES Nikola Djurica, clarinet Katharina Kang, viola Nikola Djurica, clarinet Michael Strauss, viola Mathias Tacke, violin Dmitry Kouzov, cello Shmuel Ashkenasi, violin Emanuel Gruber, cello David Ehrlich, violin Richard Masters, piano Mathias Tacke, violin Richard Masters, piano David Ehrlich, violin Our June chamber series brings music guaranteed to set your spirits soaring into the summer stars. We Drawing inspiration from many lands and folk start out with Beethoven’s Trio for Clarinet, Cello, and traditions, this evening features rich works, including Piano in B Flat Major, op. 11; Dohnányi’s Quintet for the Arutiunian Suite for Clarinet, Violin, and Piano; Piano and Strings, no. 1 in C Minor; and a buoyant the Kodály Serenade for Two Violins and Viola; and selection of Klezmer Music for Clarinet and String other repertoire. Quartet. Thursday, June 16, 2016, 7:30 PM Tuesday, June 28, 2016, 7:30 PM INFORMAL JAZZ CONCERT FEATURING CLARINET ELEGANCE AND EMOTION AND PIANO Squires Recital Salon P. Buckley Moss Art Gallery, 223 Gilbert Street, Blacksburg Nikola Djurica, clarinet Katharina Kang, viola Shmuel Ashkenasi, violin Michael Strauss, viola Nikola Djurica, clarinet Albert Newberry, piano David Ehrlich, violin Emanuel Gruber, cello Enjoy art and jazz in this casual gathering hosted by The evening’s concert puts lyricism in the spotlight, the P. -

Programme-Notes-Lau-Hui-Ping-8Y6d

Junior Recital Program Notes Trumpet Concerto in A-flat Major (1950) | Alexander Grigori Arutiunian Alexander Arutiunian (1920-2012) was an Armenian composer and pianist. He studied piano at Yerevan's Komitas Conservatory when he was 7 years old and graduated at 14 years old on the eve of World War II. The war disrupted further education for Arutiunian until 1946, where he studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory. In 1954, he was appointed as the music director of Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra, a post which he held until he reached the age of 70 (1990). He also served as full Professor at the Yerevan Conservatory as well as remained active in composition in the 1980s and early 90s. Arutiunian’s Trumpet Concerto has become a favourite in the trumpet repertoire due to its unique folk-influence, lyrical cantabile sections and virtuosic passages. However, it was written during a difficult time for Soviet composers where they were expected to compose stylistically tame music, focusing on patriotic texts or subjects. Arutiunian originally started to write it in 1943 for Zsolak Vartasarian, who was the principal trumpet in the Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra. However, Vartasarian died in the war and the concerto was not completed until 1950. As trumpet virtuoso at that time, Timofei Dokschitzer was the first to record it and make it famous. Today, this work features regularly in syllabuses, competitions and concert programmes. Although the concerto is written in a single unbroken movement but it still follows the traditional pattern of fast-slow-fast sections which contains seven sections. The first section marked andante maestoso is played with a great deal of rubato and has very little orchestra (piano) accompaniment.