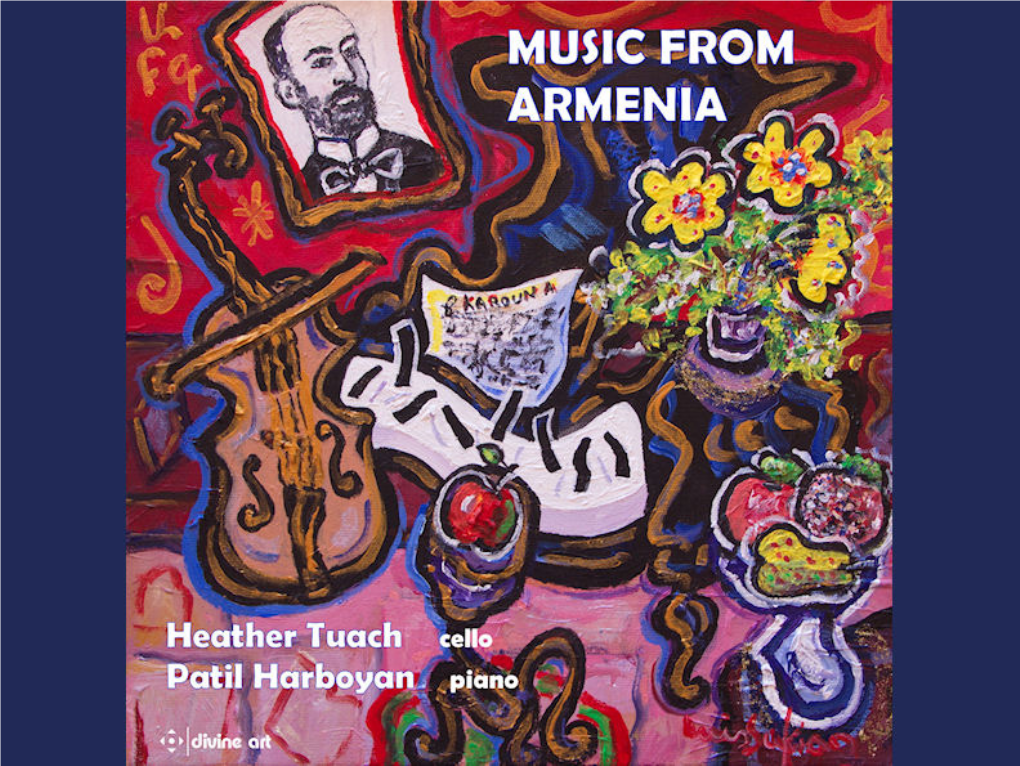

MUSIC from Armeniafor Cello and Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group Theoretical Methods in Physics GROUP - 27 Yerevan, Armenia, August 13 - 19, 2008 THIRD BULLETIN

XXVII International Colloquium on Group Theoretical Methods in Physics GROUP - 27 Yerevan, Armenia, August 13 - 19, 2008 THIRD BULLETIN This is a last BULLETIN contains the scientific programme, information concerning the preparation of the Colloquium Proceedings and other useful information of the XXVII In- ternational Colloquium on Group Theoretical Methods in Physics. We also invite you to occasionally visit the Colloquium web page at "http://theor.jinr.ru/∼group27/" for updated information and news concerning the Colloquium. 1 Invited Speakers Allahverdyan, Armen YPhI, Yerevan Belavin, Alexander ITP, Chernogolovka Bieliavsky, Pierre Catholic University of Louvian, Louvain Daskaloyannis, Costantin Aristotel University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki Doebner, Heinz-Dietrich ASI, Clausthal Draayer, Jerry Baton Rouge Exner, Pavel Nuclear Physics Institute, Rez Fjelstad, Jens CTQMP, Aarhus Gazeau, Jean-Pierre University of Paris 7, Paris Isaev, Alexey JINR, Dubna Nahm, Werner DIAS, Dublin Sheikh-Jabbari, Mohammad IPM, Tehran van Moerbeke, Pierre Catholic University of Louvian, Louvain Vourdas, A. University of Bradford, Bradford 1 2 The GROUP27 Colloquium is supported by grants from: • International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) • International Association of Mathematical Physics (IAMP) • Joint Institute for Nuclear Research • Infeld - Bogolyubov programme • State Committee of Science of the Republic of Armenia • Yerevan State University 3 Timetable Tuesday, 12 August Arrival and Registration Wednesday, 13 August Talks begin in the morning Tuesday, 19 August Conference ends in the afternoon Wednesday, 20 August Departure 30 November Deadline for submission of manuscripts for the Proceedings 4 Special Events • Tuesday, August 12, Welcome Party will be held in the Ani Plaza Hotel (20.00-22.00). • Friday, August 15, 19.30 Weyl Prize Ceremony in Komitas Chamber Music Hall (Isahakian st. -

02.12.14 Symphony FINAL.Indd

UPCOMING EVENTS Symphonic Band Concert With CSU Faculty Peter Sommer, Saxophone & Special Guest Joel Puckett, Composer-in-Residence 2/20 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 p.m. UNIVERSITY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Wind Ensemble Concert CONCERTO COMPETITION FINALS With Special Guest John Lynch, Conductor Star Search Comes to CSU 2/21 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 p.m. Wes Kenney, Conductor CSU Honor Band Concert With Special Guest John Lynch, Conductor CA 2/22 • Griffin Concert Hall • 7:30 p.m. PROGRAM Virtuoso Series Concert Alexander Arutiunian Trumpet Concerto in A-flat Major CSU Faculty Tiffany Blake, Soprano & John Seesholtz, Baritone With Dr. Annie McDonald, Piano (1920-2012) (1950) 2/24 • Organ Recital Hall • 7:30 p.m. Soloist: Robert Bonner Virtuoso Series Concert nniversary With Special Guests Christine Rutledge, Viola & David Gompper, Piano Julius Conus Violin Concerto in E Minor (1869-1942) (1896) 2/25 • Organ Recital Hall • 7:30 p.m. A Soloist: Adrián Barrera Ramos event calendar • e-newsletter registration Sergei Prokofiev Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Major, Op. 26 www.uca.colostate.edu (1891-1953) (1921) I. Andante-Allegro 5th General information: (970) 491-5529 Soloist: Yolanda Tapia Hernandez Tickets: (970) 491-ARTS (2787) Meet Me at the UCA Season “Green” Sponsor www.CSUArtsTickets.com the U e at INTERMISSION Thank you for your continued support Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 5 in E minor M (1840-1893) (1888) I. Andante-Allegro con anima II. Andante Cantabile con alcuna licenza III. Valse. Allegro moderato IV. Finale. Andante maestoso-Allegro vivace eet Wednesday, February 12, 2014 M Griffin Concert Hall, University Center for the Arts PROGRAM NOTES Friends of the UCA at Colorado State University Trumpet Concerto Alexander Arutiunian connects you to students and faculty who inspire, teach, and heal at Colorado State. -

Sharing Christmas Joy in Armenia and Artsakh

AMYRIGA#I HA# AVYDARAN{AGAN UNGYRAGXOV:IVN ARMENIAN MISSIONARY ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA AMAA NEWS LI 1 Sharing Christmas Joy in Jan-Feb-March 2017 Armenia and Artsakh P. 11 CONTENTS January•February•March 2017 /// LI1 3 Editorial Against the Tide By Zaven Khanjian 4 Inspirational Corner A Resurrection Reflection By Rev. Haig Kherlopian 1918 2018 5 Around the Globe Armenian Evangelical Church of New York By Peter Kougasian, Esq. 6 Almost a Hundred Years Later By Heather Ohaneson, Ph.D. 7 In Memoriam: Samuel Chekijian 8 Meet Our Veteran Pastors Rev. Dr. Joseph Alexanian AMAA NEWS 9 Remembering Hrant Dink By Zaven Khanjian is a publication of 10 Stitched With Love By Betty Cherkezian The Armenian Missionary Association of America 11 AMAA Shares Christmas Joy with Children in Armenia and Karabagh 31 West Century Road, Paramus, NJ 07652 Tel: (201) 265-2607; Fax: (201) 265-6015 12 AMAA's Humanitarian Aid to the Armenian Army E-mail: [email protected] 13 Armenian Children's Milk Fund Website: www.amaa.org (ISSN 1097-0924) 14 A Time of Ending and Sending By Jeannette Keshishian 15 New Missionaries Go Into the World to Preach, To Serve By Zaven Khanjian The AMAA is a tax-exempt, not for profit 17 God's Faithfulness By Nanor Kelenjian Akbasharian organization under IRS Code Section 501(c)(3) 18 Relief is Still Needed in Syria Zaven Khanjian, Executive Director/CEO 19 AMAA's Syria LifeLine Relocates 113 Families to the Homeland Levon Filian, West Coast Executive Director David Aynejian, Director of Finance 20 First Armenian Evangelical Church of Montreal -

Download Booklet

Charming Cello BEST LOVED GABRIEL SCHWABE © HNH International Ltd 8.578173 classical cello music Charming Cello the 20th century. His Sérénade espagnole decisive influence on Stravinsky, starting a Best loved classical cello music uses a harp and plucked strings in its substantial neo-Classical period in his writing. A timeless collection of cello music by some of the world’s greatest composers – orchestration, evoking Spain in what might including Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Vivaldi and others. have been a recollection of Glazunov’s visit 16 Goodall: And the Bridge is Love (excerpt) to that country in 1884. ‘And the Bridge is Love’ is a quotation from Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of 1 6 Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750) Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) 14 Ravel: Pièce en forme de habanera San Luis Rey which won the Pulitzer Prize Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, 2:29 Cello Concerto in C major, 9:03 (arr. P. Bazelaire) in 1928. It tells the story of the collapse BWV 1007 – I. Prelude Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato Swiss by paternal ancestry and Basque in 1714 of ‘the finest bridge in all Peru’, Csaba Onczay (8.550677) Maria Kliegel • Cologne Chamber Orchestra through his mother, Maurice Ravel combined killing five people, and is a parable of the Helmut Müller-Brühl (8.555041) 2 Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) his two lineages in a synthesis that became struggle to find meaning in chance and in Le Carnaval des animaux – 3:07 7 Robert SCHUMANN (1810–1856) quintessentially French. His Habanera, inexplicable tragedy. -

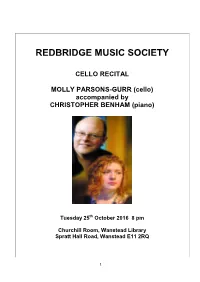

Molly Parson-Gurr Recital Programme 25 Oct 2016

REDBRIDGE MUSIC SOCIETY CELLO RECITAL MOLLY PARSONS-GURR (cello) accompanied by CHRISTOPHER BENHAM (piano) Tuesday 25th October 2016 8 pm Churchill Room, Wanstead Library Spratt Hall Road, Wanstead E11 2RQ 1 PROGRAMME ‘Arioso’ for cello and piano J S Bach (1685 – 1750) Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 J S Bach (1685 – 1750) i Prelude ii Allemande iii Courante iv Sarabande v Minuets 1 & 2 vi Gigue Drei Fantasiestücke for cello and piano Op. 73 Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) i Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with expression) ii Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, light) iii Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with fire) INTERVAL Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano Op 19 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) i Lento – Allegro moderato ii Allegro scherzando iii Andante iv Allegro mosso PROGRAMME NOTES J S Bach: Arioso for cello and piano & Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 The ‘arioso’ you will hear at this evening’s recital is an arrangement for cello and piano of the sinfonia which opens Bach’s church Cantata "Ich steh`mit einem Fuss im Grabe" (“I am standing with one foot in the grave”) BWV 156 first performed in Leipzig in 1729. The original sinfonia was scored for oboe, strings and continuo and was most likely derived from an early F major oboe concerto of Bach’s; it appears also as the middle movement (largo) of Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto No.5 in F minor BWV 1056. There have been many arrangements of the ‘arioso’ including those for trumpet and piano, violin and piano, solo guitar and also for full orchestra (the latter arr. -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

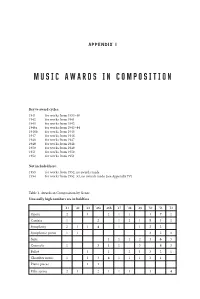

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

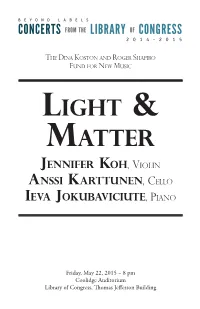

Light & Matter

THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO Friday, May 22, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions, contemporary music and its performers. Presented in association with the European Month of Culture Part of National Chamber Music Month Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Friday, May 22, 2015 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO • Program CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Sonate pour Violoncelle et Piano (1915) Prologue: Lent, Sostenuto e molto risoluto–(Agitato)–au Mouvt (largement déclamé)–Rubato–au Mouvt (poco animando)–Lento Sérénade: Modérément animé–Fuoco–Mouvt–Vivace–Meno mosso poco– Rubato–Presque lent–1er Mouvt–au Mouvt– Finale: Animé, Léger et nerveux–Rubato–1er Mouvt–Con fuoco ed appassionato–Lento. -

Program Notes Written by Earle Cheshire-Wood

Concert Notes – February 21, 2021 Earle Cheshire-Wood Suite Hellénique ( Kalamatianos, Valse, Kritis) Pedro Itturalde (1929-2020) Pedro Itturralde was a Spanish saxophonist who learned from his father, performed professionally by age eleven and later led his own quartet that combined aspects of jazz and flamenco. Despite this, Iturralde has said “ Lo que yo hice no era fusión. Si unes jazz y flamenco, uno de los dos muere ", meaning “What I did was not fusion. If you join jazz and flamenco, one of the two dies”. His piece Suite Hellénique was composed for piano and saxophone around 2001. Itturalde passed away last year in Madrid, but his timeless compositions live on through musicians today. Elegie “In Memory of Aram Khachaturian” Arno Babajanian (1921-1983) Babajanian wrote this piece in memory of Aram Khachaturian, the composer who, after seeing his talent as a young child, proposed that he be given proper musical training. Babajanian was an Armenian Soviet who toured the Soviet Union and Europe performing various concerts. He was even named a People’s Artist of the USSR. Both Babajanian and Khachaturian were Armenian, and much of the music they composed drew from the country’s folklore and folk music. Elegie was originally written for solo piano in 1978 and added to his successes and numerous awards received from the USSR and Armenian SSR. Danza de la Moza Donosa (from Danzas Argentinas Op.2, No.2) Alberto Ginastera (1916-1983) Danza de la Moza Donosa translates to “Dance of the Beautiful Maiden”. Ginastera composed this as a soft, pleasant dance for solo piano in 6/8 time. -

Arno Babajanian 13

Sergei Rachmaninoff 19. Variation 7: Vivace 0:27 Préludes 20. Variation 8: Adagio misterioso 0:58 1. Op. 3, No. 2 in C sharp minor - Lento 3:51 21. Variation 9: Un poco piu mosso 0:57 2. Op. 23, No. 5 in G minor - Alla marcia 3:52 22. Variation 10: Allegro scherzando 0:39 3. Op. 23, No. 6 in E flat major - Andante 3:11 23. Variation 11: Allegro vivace 0:25 4. Op. 23, No. 7 in C minor - Allegro 2:54 24. Variation 12: L’istesso tempo 0:35 5. Op. 32, No. 5 in G major - Moderato 3:07 25. Variation 13: Agitato 0:32 6. Op. 32, No. 10 in B minor - Lento 4:41 26. Intermezzo 1:19 7. Op. 32, No. 12 in G sharp minor - Allegro 2:43 27. Variation 14: Andante (come prima) 0:58 28. Variation 15: L’istesso tempo 1:18 Etudes-Tableaux 29. Variation 16: Allegro vivace 0:30 8. Op. 33, No. 6 in E flat minor - Non allegro 1:48 30. Variation 17: Meno mosso 1:05 9. Op. 39, No. 1 in C minor - Allegro agitato 3:36 31. Variation 18: Allegro con brio 0:36 10. Op. 39, No. 5 in E flat minor - Appassionato 5:04 32. Variation 19: Piu mosso. Agitato 0:32 11. Op. 39, No. 6 in A minor - Allegro 3:03 33. Variation 20: Piu mosso 0:58 34. Coda: Andante 1:31 Variations on a Theme of Corelli 12. Theme: Andante 0:57 Arno Babajanian 13. -

The History and Usage of the Tuba in Russia

The History and Usage of the Tuba in Russia D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By James Matthew Green, B.A., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2015 Document Committee: Professor James Akins, Advisor Professor Joseph Duchi Dr. Margarita Mazo Professor Bruce Henniss ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright by James Matthew Green 2015 ! ! ! ! ! ! Abstract Beginning with Mikhail Glinka, the tuba has played an important role in Russian music. The generous use of tuba by Russian composers, the pedagogical works of Blazhevich, and the solo works by Lebedev have familiarized tubists with the instrument’s significance in Russia. However, the lack of available information due to restrictions imposed by the Soviet Union has made research on the tuba’s history in Russia limited. The availability of new documents has made it possible to trace the history of the tuba in Russia. The works of several composers and their use of the tuba are examined, along with important pedagogical materials written by Russian teachers. ii Dedicated to my wife, Jillian Green iii Acknowledgments There are many people whose help and expertise was invaluable to the completion of this document. I would like to thank my advisor, professor Jim Akins for helping me grow as a musician, teacher, and person. I would like to thank my committee, professors Joe Duchi, Bruce Henniss, and Dr. Margarita Mazo for their encouragement, advice, and flexibility that helped me immensely during this degree. I am indebted to my wife, Jillian Green, for her persistence for me to finish this document and degree.