Beethoven Cello Sonata Op 102 No 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

A Discussion of the Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op

A DISCUSSION OF THE PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN D MINOR, OP. 14, BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV A PAPER ACCOMPANYING A THREE CREDIT-HOUR CREATIVE PROJECT RECITAL SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC BY QINYUAN LIN DR. ROBERT PALMER‐ ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 Preface The goal of this paper is to introduce the piece, provide historical background, and focus on the musical analysis of the sonata. The introduction of the piece will include a brief biography of Sergei Prokofiev and the circumstance in which the piece was composed. A general overview of the composition, performance, and perception of this piece will be discussed. The bulk of the paper will focus on the musical analysis of Piano Sonata No. 2 from my perspective as a performer of the piece. It will be broken into four sections, one each for the four movements in the sonata. In the discussion for each movement, I will analyze the forms used as well as required techniques and difficulties to be considered by the pianist. The conclusion will summarize the discussion. i Table of Contents Preface ________________________________________________________________ i Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 The First Movement: Allegro, ma non troppo __________________________________ 5 The Second Movement: Scherzo ____________________________________________ 9 The Third Movement: Andante ____________________________________________ 11 The Fourth Movement: Vivace ____________________________________________ 13 Conclusion ____________________________________________________________ 17 Bibliography __________________________________________________________ 18 ii Introduction Sergei Prokofiev was born in 1891 to parents Sergey and Mariya and grew up in comfortable circumstances. His mother, Mariya, had a feeling for the arts and gave the young Prokofiev his first piano lessons at the age of four. -

Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 08:37 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes --> Voir l’erratum concernant cet article Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt Volume 9, numéro 1, 1988 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014927ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Batt, R. (1988). Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 9(1), 157–201. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1988 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE OF TRANSITIONS IN SONATA-FORM MUSIC OF MOZART Robert Batt The transition, sometimes referred to as the bridge, is usually regarded as the section of sonata form responsible for modulating from the pri• mary to the secondary key as well as for effecting a structural contrast between the two thematic sections. -

Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin

Analysis of Scriabin’s Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) was a Russian composer and pianist. An early modern composer, Scriabin’s inventiveness and controversial techniques, inspired by mysticism, synesthesia, and theology, contributed greatly to redefining Russian piano music and the modern musical era as a whole. Scriabin studied at the Moscow Conservatory with peers Anton Arensky, Sergei Taneyev, and Vasily Safonov. His ten piano sonatas are considered some of his greatest masterpieces; the first, Piano Sonata No. 1 In F Minor, was composed during his conservatory years. His Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 was composed in 1912-13 and, more than any other sonata, encapsulates Scriabin’s philosophical and mystical related influences. Sonata No. 9 (“Black Mass”), Op. 68 is a single movement and lasts about 8-10 minutes. Despite the one movement structure, there are eight large tempo markings throughout the piece that imply a sense of slight division. They are: Moderato Quasi Andante (pg. 1), Molto Meno Vivo (pg. 7), Allegro (pg. 10), Allegro Molto (pg. 13), Alla Marcia (pg. 14), Allegro (p. 15), Presto (pg. 16), and Tempo I (pg. 16). As was common in Scriabin’s later works, the piece is extremely chromatic and atonal. Many of its recurring themes center around the extremely dissonant interval of a minor ninth1, and features several transformations of its opening theme, usually increasing in complexity in each of its restatements. Further, a common Scriabin quality involves his use of 1 Wise, H. Harold, “The relationship of pitch sets to formal structure in the last six piano sonatas of Scriabin," UR Research 1987, p. -

Color in Your Own Cello! Worksheet 1

Color in your own Cello! Worksheet 1 Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a Violin, Viola, Cello, and Bass. Circle the Cello! How did you know this was the Cello? In his video, Will talked about a smooth, connected style of playing when he played the melody in The Swan. What is this style with long, flowing notes called? When musicians pluck the strings on their instrument, does it make the sounds very short or very long? What is it called when musicians pluck the strings? What does the Cello sound like to you? How does that sound make you feel? Use the back of this sheet to write or draw what the sound of the Cello makes you think of! Worksheet 1 - ANSWERS Circle the answer! This instrument is the: Violin Viola Cello Bass Which way is this instrument played? On the shoulder On the ground Is this instrument bigger or smaller than the violin? Bigger Smaller BONUS: In the video, Will said when musicians use their fingers to pluck the strings instead of using a bow, it is called: Piano Pizazz Pizzicato Potato Worksheet 2 - ANSWERS ALL ABOUT THE CELLO Below are a violin, viola, cello, and bass. -

Nxta Cello Instructions STAND Open the Legs Wide for Stability, and Secure in Place with Thumb Screw Clamp

NXTa Cello Instructions STAND Open the legs wide for stability, and secure in place with thumb screw clamp. Mount the instrument to the stand using the large (5/16”) thumb screw at the top of the stand. Using the adjustment knobs, it is possible to adjust the height, angle, and tilt of the instrument. CONTROLS Knob 1 Volume – rotary control Knob 2 Tone – rotary control, clockwise for full treble, counter-clockwise to cut treble. Dual Output Mode – push-pull control, in for Passive Mode, out for Active Mode. Active Mode – Using the supplied charger, connect the NXTa to any AC outlet for 60 seconds. This will fuel the capacitor-powered active circuit for up to 16 hours of performance time. The instrument can then be plugged straight into any low or high impedance device, no direct box necessary. Passive Mode* – The NXTa can be played in this mode with an amplifier with an impedance of 1 meg ohm or greater (3-10 meg ohm recommended) or with a direct box. Switch Arco/Pizzicato Mode selection, toggle up for Arco, toggle down for Pizzicato The design of the Polar™ Pickup System enables you to choose between two distinct attack and decay characteristics: Arco Mode is for massive attack and relatively fast decay, optimal for bowed and percussive plucked sound. Pizzicato Mode is for a smooth attack and long decay, optimal for plucked, sustained sound. This mode is not recommended for bowing. Note that the Polar™ pickup allows the player to control attack and decay parameters. Pizzicato Mode is for a smoother attack and longer decay when plucked. -

The Use of Scordatura in Heinrich Biber's Harmonia Artificioso-Ariosa

RICE UNIVERSITY TUE USE OF SCORDATURA IN HEINRICH BIBER'S HARMONIA ARTIFICIOSO-ARIOSA by MARGARET KEHL MITCHELL A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE aÆMl Dr. Anne Schnoebelen, Professor of Music Chairman C<c g>'A. Dr. Paul Cooper, Professor of- Music and Composer in Ldence Professor of Music ABSTRACT The Use of Scordatura in Heinrich Biber*s Harmonia Artificioso-Ariosa by Margaret Kehl Mitchell Violin scordatura, the alteration of the normal g-d'-a'-e" tuning of the instrument, originated from the spirit of musical experimentation in the early seventeenth century. Closely tied to the construction and fittings of the baroque violin, scordatura was used to expand the technical and coloristlc resources of the instrument. Each country used scordatura within its own musical style. Al¬ though scordatura was relatively unappreciated in seventeenth-century Italy, the technique was occasionally used to aid chordal playing. Germany and Austria exploited the technical and coloristlc benefits of scordatura to produce chords, Imitative passages, and special effects. England used scordatura primarily to alter the tone color of the violin, while the technique does not appear to have been used in seventeenth- century France. Scordatura was used for possibly the most effective results in the works of Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704), a virtuoso violin¬ ist and composer. Scordatura appears in three of Biber*s works—the "Mystery Sonatas", Sonatae violino solo, and Harmonia Artificioso- Ariosa—although the technique was used for fundamentally different reasons in each set. In the "Mystery Sonatas", scordatura was used to produce various tone colors and to facilitate certain technical feats. -

Download Booklet

Charming Cello BEST LOVED GABRIEL SCHWABE © HNH International Ltd 8.578173 classical cello music Charming Cello the 20th century. His Sérénade espagnole decisive influence on Stravinsky, starting a Best loved classical cello music uses a harp and plucked strings in its substantial neo-Classical period in his writing. A timeless collection of cello music by some of the world’s greatest composers – orchestration, evoking Spain in what might including Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Vivaldi and others. have been a recollection of Glazunov’s visit 16 Goodall: And the Bridge is Love (excerpt) to that country in 1884. ‘And the Bridge is Love’ is a quotation from Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of 1 6 Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750) Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) 14 Ravel: Pièce en forme de habanera San Luis Rey which won the Pulitzer Prize Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, 2:29 Cello Concerto in C major, 9:03 (arr. P. Bazelaire) in 1928. It tells the story of the collapse BWV 1007 – I. Prelude Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato Swiss by paternal ancestry and Basque in 1714 of ‘the finest bridge in all Peru’, Csaba Onczay (8.550677) Maria Kliegel • Cologne Chamber Orchestra through his mother, Maurice Ravel combined killing five people, and is a parable of the Helmut Müller-Brühl (8.555041) 2 Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) his two lineages in a synthesis that became struggle to find meaning in chance and in Le Carnaval des animaux – 3:07 7 Robert SCHUMANN (1810–1856) quintessentially French. His Habanera, inexplicable tragedy. -

Season 2012-2013

27 Season 2012-2013 Thursday, December 13, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, December 14, at 8:00 Saturday, December 15, Gianandrea Noseda Conductor at 8:00 Alisa Weilerstein Cello Borodin Overture to Prince Igor Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 I. Adagio—Moderato— II. Lento—Allegro molto III. Adagio IV. Allegro—Moderato—[Cadenza]—Allegro, ma non troppo—Poco più lento—Adagio—Allegro molto Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 29 (“Polish”) I. Introduzione ed allegro: Moderato assai (tempo di marcia funebre)—Allegro brillante II. Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice III. Andante elegiaco IV. Scherzo: Allegro vivo V. Finale: Allegro con fuoco (tempo di polacca) This program runs approximately 1 hour, 55 minutes. The December 14 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. 228 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin Renowned for its distinctive vivid world of opera and Orchestra boasts a new sound, beloved for its choral music. partnership with the keen ability to capture the National Centre for the Philadelphia is home and hearts and imaginations Performing Arts in Beijing. the Orchestra nurtures of audiences, and admired The Orchestra annually an important relationship for an unrivaled legacy of performs at Carnegie Hall not only with patrons who “firsts” in music-making, and the Kennedy Center support the main season The Philadelphia Orchestra while also enjoying a at the Kimmel Center for is one of the preeminent three-week residency in the Performing Arts but orchestras in the world. Saratoga Springs, N.Y., and also those who enjoy the a strong partnership with The Philadelphia Orchestra’s other area the Bravo! Vail Valley Music Orchestra has cultivated performances at the Mann Festival. -

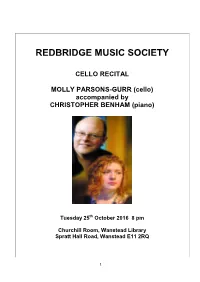

Molly Parson-Gurr Recital Programme 25 Oct 2016

REDBRIDGE MUSIC SOCIETY CELLO RECITAL MOLLY PARSONS-GURR (cello) accompanied by CHRISTOPHER BENHAM (piano) Tuesday 25th October 2016 8 pm Churchill Room, Wanstead Library Spratt Hall Road, Wanstead E11 2RQ 1 PROGRAMME ‘Arioso’ for cello and piano J S Bach (1685 – 1750) Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 J S Bach (1685 – 1750) i Prelude ii Allemande iii Courante iv Sarabande v Minuets 1 & 2 vi Gigue Drei Fantasiestücke for cello and piano Op. 73 Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) i Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with expression) ii Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, light) iii Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with fire) INTERVAL Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano Op 19 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) i Lento – Allegro moderato ii Allegro scherzando iii Andante iv Allegro mosso PROGRAMME NOTES J S Bach: Arioso for cello and piano & Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 The ‘arioso’ you will hear at this evening’s recital is an arrangement for cello and piano of the sinfonia which opens Bach’s church Cantata "Ich steh`mit einem Fuss im Grabe" (“I am standing with one foot in the grave”) BWV 156 first performed in Leipzig in 1729. The original sinfonia was scored for oboe, strings and continuo and was most likely derived from an early F major oboe concerto of Bach’s; it appears also as the middle movement (largo) of Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto No.5 in F minor BWV 1056. There have been many arrangements of the ‘arioso’ including those for trumpet and piano, violin and piano, solo guitar and also for full orchestra (the latter arr.