David Finckel, Cello Wu Han, Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

César Franck's Violin Sonata in a Major

Honors Program Honors Program Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 C´esarFranck's Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer's Influence on the Violin Repertory Clara Fuhrman University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/honors program theses/21 César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer’s Influence on the Violin Repertory By Clara Fuhrman Maria Sampen, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements as a Coolidge Otis Chapman Scholar. University of Puget Sound, Honors Program Tacoma, Washington April 18, 2016 Fuhrman !2 Introduction and Presentation of My Argument My story of how I became inclined to write a thesis on Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major is both unique and essential to describe before I begin the bulk of my writing. After seeing the famously virtuosic violinist Augustin Hadelich and pianist Joyce Yang give an extremely emotional and perfected performance of Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major at the Aspen Music Festival and School this past summer, I became addicted to the piece and listened to it every day for the rest of my time in Aspen. I always chose to listen to the same recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata by violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk, in my opinion the highlight of their album entitled French Impressions, released in 2012. After about a month of listening to the same recording, I eventually became accustomed to every detail of their playing, and because I had just started learning the Sonata myself, attempted to emulate what I could remember from the recording. -

Phd April 2019 Pp

The University of Adelaide Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts Revisiting George Enescu’s 1921 Bucharest Recital Series: a performance-based investigation with recordings and exegesis. by Elizabeth Layton submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Adelaide, April 2019 Table of Contents Abstract 5 Declaration 6 Acknowledgements 7 List of Musical Examples 8 List of Tables 11 Introduction 12 PART A: Sound recordings 22 A.1 CD 1 Tracks 1-4 Pierre de Bréville, Sonata no. 1 in C # minor 39:17 Tracks 5-8 Gabriel Fauré, Sonata no. 1 in A major, Op. 13 26:14 A.2 CD 2 Tracks 1-4 André Gédalge, Sonata no. 1 in G major, Op. 12 23:39 Tracks 5-7 Claude Debussy, Sonata in G minor (performance 1) 13:44 Tracks 8-10 Claude Debussy, Sonata in G minor (performance 2) 13:36 A.3 CD 3 Tracks 1-3 Ferruccio Busoni, Sonata no. 2 in E minor, Op. 36a 34:25 Tracks 4-7 Zygmunt Stojowski, Sonata no. 2 in E minor, Op. 37 29:30 A.4 CD 4 Tracks 1-4 Louis Vierne, Sonata in G minor, Op. 23 32:44 Tracks 5-7 Stan Golestan, Sonata in E flat major 26:56 Tracks 8-10 George Enescu, Sonata in F minor, Op. 6 22:34 PART B: Exegesis Chapter 1 George Enescu: Musician, and his path to the 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 27 1.1 Understanding the context and motivation behind the series 35 2 Chapter 2 The 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 38 2.1 Recital 1: Haydn, d’Indy, Bertelin 38 2.2 Recital 2: Mozart, Busoni, Vierne 39 2.3 Recital 3: Sjögren, Schubert, Lauweryns 41 2.4 Recital 4: Weingartner, Stojowski, Beethoven 42 2.5 Recital 5: Bargiel, Haydn, Golestan 42 2.6 Recital 6: Le Boucher, Mozart, Saint-Saëns 43 2.7 Recital 7: Gédalge, Dvorák, Debussy, Schumann 44 2.8 Recital 8: Huré, Bach, Lekeu 45 2.9 Recital 9: Beethoven, Fauré, Franck 46 2.10 Recital 10: Gallon, de Bréville, Beethoven 48 2.11 Recital 11: Magnard, Le Flem, Brahms 49 2.12 Recital 12: Franck, Enescu, Beethoven 49 Chapter 3 Performance notes on nine sonatas selected from the 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 3.1 Pierre de Bréville, Sonata no. -

Rachael Dobosz Senior Recital

Thursday, May 11, 2017 • 9:00 p.m Rachael Dobosz Senior Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Thursday, May 11, 2017 • 9:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Rachael Dobosz, flute Senior Recital Beilin Han, piano Sofie Yang, violin Caleb Henry, viola Philip Lee, cello PROGRAM César Franck (1822-1890) Sonata for Flute and Piano Allegretto ben Moderato Allegro Ben Moderato: Recitativo- Fantasia Allegretto poco mosso Beilin Han, piano Lowell Liebermann (B. 1961) Sonata for Flute and Piano Op.23 Lento Presto Beilin Han, piano Intermission John La Montaine (1920-2013) Sonata for Piccolo and Piano Op.61 With driving force, not fast Sorrowing Searching Playful Beilin Han, piano Rachael Dobosz • May 11, 2017 Program Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Quartet in C Major, KV 285b Allegro Andantino, Theme and Variations Sofie Yang, violin Caleb Henry, viola Philip Lee, cello Rachael Dobosz is from the studio of Alyce Johnson. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Rachael Dobosz • May 11, 2017 Program notes PROGRAM NOTES César Franck (1822-1890) Sonata for Flute and Piano Duration: 30 minutes César Franck was a well known organist in Paris who taught at the Paris Conservatory and was appointed to the organist position at the Basilica of Sainte-Clotilde. From a young age, Franck showed promise as a great composer and was enrolled in the Paris Conservatory by his father where he studied with Anton Reicha. -

Graduate Recital: Robin Alfieri, Violin Robin Alfieri

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 2-5-2011 Graduate Recital: Robin Alfieri, violin Robin Alfieri Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Alfieri, Robin, "Graduate Recital: Robin Alfieri, violin" (2011). All Concert & Recital Programs. 19. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/19 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Graduate Recital: Robin Alfieri, violin Mary Holzhauer, piano and harpsichord Rachel Fannick, piano Bradley Pipenger, clarinet Hockett Family Recital Hall Saturday, February 5, 2011 4:00 p.m. Program Suite in A major, BWV 1025 J.S. Bach after Fantasia Silvius Leopold Weiss Courante 1685-1750, 1686-1750 Entrée Rondeau Sarabande Menuet Allegro Serenade for Three Peter Schickele Dances b. 1935 Songs Variations Rachel Fannick, piano Bradley Pipenger, clarinet Intermission Concerto in A major, KV 219 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Allegro aperto 1756-1791 Sonata in D major, Op. 94b Sergei Prokofiev Moderato 1891-1953 Presto Andante Allegro con brio This is a Graduate Recital in partial fulfillment of a Master of Music in Suzuki Pedagogy. Robin Alfieri is from the studios of Nicholas DiEugenio and Sanford Reuning. Program Notes Suite in A Major, BWV 1025 Suite in A major, which has been attributed to J.S. Bach (1685-1750), was originally written by Silvius Leopold Weiss (1686-1750). Weiss was regarded as the greatest lutenist of the Baroque period and was a contemporary of Bach. -

Monday Playlist

February 3, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “To send light into the darkness of men's hearts—such is the duty of the artist.” — Robert Schumann Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Incidental Music ~ A Midsummer Night's Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Cleveland Orchestra/Szell CBS Records 37760 07464377602 Dream 00:32 Buy Now! Bach Selections ~ The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 00:51 Buy Now! Rogers Reverie for Cello and Piano Wulfhorst/Radell Self-published n/a 884501920247 01:01 Buy Now! Tchaikovsky Marche slave, Op. 31 Montreal Symphony/Dutoit London 417 300 028941730022 01:13 Buy Now! Brahms Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68 Boston Symphony/Nelsons BSO 1703 828020003425 Musical Heritage 02:00 Buy Now! Mozart Sonata in D for 2 pianos, K. 448 Misha and Cipa Dichter 5379317 717794793123 Society Concertante in B flat for Flute and Clarinet, Galway/Meyer/Wurttemberg Chamber 02:25 Buy Now! Danzi RCA Victor 61976 090266197620 Op. 41 Orchestra/Faerber 02:47 Buy Now! Pachelbel Suite in B flat for Strings Paillard Chamber Orchestra/Paillard Erato 98475 745099847524 03:00 Buy Now! Sibelius Karelia Suite, Op. 11 Finnish Radio Symphony/Saraste RCA 7765 07863577652 03:15 Buy Now! Busoni Berceuse elegiaque, Op. 42 Hong Kong Philharmonic/Wong Naxos 8.555373 747313537327 03:27 Buy Now! Schubert Piano Sonata in C minor, D. 958 Sviatoslav Richter Regis 1049 5055031310494 Danczowka/Polish National Radio-TV 04:01 Buy Now! Karlowicz Violin Concerto, Op. -

Download Booklet

Charming Cello BEST LOVED GABRIEL SCHWABE © HNH International Ltd 8.578173 classical cello music Charming Cello the 20th century. His Sérénade espagnole decisive influence on Stravinsky, starting a Best loved classical cello music uses a harp and plucked strings in its substantial neo-Classical period in his writing. A timeless collection of cello music by some of the world’s greatest composers – orchestration, evoking Spain in what might including Beethoven, Haydn, Schubert, Vivaldi and others. have been a recollection of Glazunov’s visit 16 Goodall: And the Bridge is Love (excerpt) to that country in 1884. ‘And the Bridge is Love’ is a quotation from Thornton Wilder’s novel The Bridge of 1 6 Johann Sebastian BACH (1685–1750) Franz Joseph HAYDN (1732–1809) 14 Ravel: Pièce en forme de habanera San Luis Rey which won the Pulitzer Prize Bach: Cello Suite No. 1 in G major, 2:29 Cello Concerto in C major, 9:03 (arr. P. Bazelaire) in 1928. It tells the story of the collapse BWV 1007 – I. Prelude Hob.VIIb:1 – I. Moderato Swiss by paternal ancestry and Basque in 1714 of ‘the finest bridge in all Peru’, Csaba Onczay (8.550677) Maria Kliegel • Cologne Chamber Orchestra through his mother, Maurice Ravel combined killing five people, and is a parable of the Helmut Müller-Brühl (8.555041) 2 Camille SAINT-SAËNS (1835–1921) his two lineages in a synthesis that became struggle to find meaning in chance and in Le Carnaval des animaux – 3:07 7 Robert SCHUMANN (1810–1856) quintessentially French. His Habanera, inexplicable tragedy. -

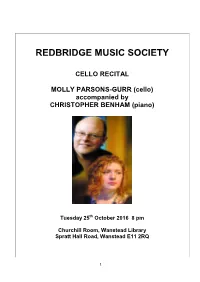

Molly Parson-Gurr Recital Programme 25 Oct 2016

REDBRIDGE MUSIC SOCIETY CELLO RECITAL MOLLY PARSONS-GURR (cello) accompanied by CHRISTOPHER BENHAM (piano) Tuesday 25th October 2016 8 pm Churchill Room, Wanstead Library Spratt Hall Road, Wanstead E11 2RQ 1 PROGRAMME ‘Arioso’ for cello and piano J S Bach (1685 – 1750) Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 J S Bach (1685 – 1750) i Prelude ii Allemande iii Courante iv Sarabande v Minuets 1 & 2 vi Gigue Drei Fantasiestücke for cello and piano Op. 73 Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) i Zart und mit Ausdruck (Tender and with expression) ii Lebhaft, leicht (Lively, light) iii Rasch und mit Feuer (Quick and with fire) INTERVAL Sonata in G minor for Cello and Piano Op 19 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) i Lento – Allegro moderato ii Allegro scherzando iii Andante iv Allegro mosso PROGRAMME NOTES J S Bach: Arioso for cello and piano & Suite No. 1 in G major for solo cello BWV 1007 The ‘arioso’ you will hear at this evening’s recital is an arrangement for cello and piano of the sinfonia which opens Bach’s church Cantata "Ich steh`mit einem Fuss im Grabe" (“I am standing with one foot in the grave”) BWV 156 first performed in Leipzig in 1729. The original sinfonia was scored for oboe, strings and continuo and was most likely derived from an early F major oboe concerto of Bach’s; it appears also as the middle movement (largo) of Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto No.5 in F minor BWV 1056. There have been many arrangements of the ‘arioso’ including those for trumpet and piano, violin and piano, solo guitar and also for full orchestra (the latter arr. -

The Development of the French Violin Sonata

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Tasmania Open Access Repository THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE FRENCH VIOLIN SONATA (1860 – 1910) BY DAVID ROGER LE GUEN B.Mus., The Australian National University, 1999 M.Mus., The University of Tasmania, 2001 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Violin Performance) University of Tasmania Hobart (May, 2006) ii DECLARATION This exegesis contains the results of research carried out at the University of Tasmania Conservatorium of Music between 2003 and 2006. It contains no material that, to my knowledge, has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information that is duly acknowledged in the exegesis. I declare that this exegesis is my own work and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where clear acknowledgement or reference has been made in the text. This exegesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Date: David Le Guen iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the supervisors of my exegesis Dr Anne-Marie Forbes, Dr Marina Phillips and my violin teachers, Mr. Yun Yi Ma and Mr. Peter Tanfield, for their guidance and support throughout my studies. My special thanks to Professor Jan Sedivka, my mentor, who not only provided me with the inspiration for undertaking this research, but whose words of wisdom and support have also given me so much joy and motivation throughout my years of study in Hobart. -

Vorwort Bei Paris Nieder (Heute Quincy-Sous- Und Namentlich Die Neue Sonate – Wie Sénart)

Vorwort bei Paris nieder (heute Quincysous und namentlich die neue Sonate – wie Sénart). Den Datierungen am Ende der derum vom Duo Ysaÿe/BordesPène vier Sätze zufolge – 24. August, 1., 8. vorgetragen – fand begeisterte Zustim und 15. September 1886 – ging die mung. Komposition sehr rasch von statten. Al Zu diesem Zeitpunkt hatte Franck Ein Großteil der heute fest im Konzert lerdings trägt die Handschrift deut die Stichvorlage, eine heute verscholle repertoire verankerten Werke César lich den Charakter eines noch nicht ne, vermutlich eigenhändige Abschrift Francks (1822 – 90) – etwa das Kla ganz vollständig ausgearbeiteten Ar der Partitur, bereits dem Pariser Ver vierquintett, das Streichquartett, die beitsmanuskripts. In der rasch folgen leger Julien Hamelle übergeben; der Variations symphoniques für Klavier den zweiten Niederschrift vervollstän am 14. November begonnene Stich (vgl. und Orchester oder die Symphonie digte Franck das Manuskript zur end Fauquet, Franck, S. 644) war dann je dmoll – entstand erst in den letzten gültigen Partitur und arbeitete außer doch aus unbekannten Gründen ins Lebensjahren des Komponisten. Dazu dem einige Passagen in den Sätzen II Stocken geraten, sodass sich die Veröf zählt auch seine 1886 geschriebene und III um. Hinzu kam nun auch die fentlichung bis ins nachfolgende Früh Violinsonate Adur, die sich jedoch Widmung an den jungen belgischen jahr hinzog. In einem Brief Francks im Gegensatz zu anderen Spätwerken Geiger Eugène Ysaÿe (1858 – 1931), an Hamelle vom 9. Februar 1887 heißt noch zu seinen Lebzeiten im Kon den Franck durch Vermittlung von es: „Ich sende Ihnen hiermit die Vio zertsaal durchsetzen konnte. Für die Henry Vieuxtemps 1877 in Paris ken linstimme meiner Sonate zurück, eine „bande à Franck“, wie Francks engerer nengelernt und der mit seiner makello weitere Fahne ist nicht mehr nötig. -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

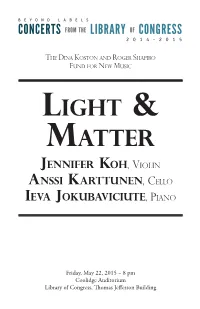

Light & Matter

THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO Friday, May 22, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions, contemporary music and its performers. Presented in association with the European Month of Culture Part of National Chamber Music Month Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Friday, May 22, 2015 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO • Program CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Sonate pour Violoncelle et Piano (1915) Prologue: Lent, Sostenuto e molto risoluto–(Agitato)–au Mouvt (largement déclamé)–Rubato–au Mouvt (poco animando)–Lento Sérénade: Modérément animé–Fuoco–Mouvt–Vivace–Meno mosso poco– Rubato–Presque lent–1er Mouvt–au Mouvt– Finale: Animé, Léger et nerveux–Rubato–1er Mouvt–Con fuoco ed appassionato–Lento. -

Lionel Tertis, York Bowen, and the Rise of the Viola

THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND A THESIS IN Musicology Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC by WILLIAM KENTON LANIER B.A., Thomas Edison State University, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 WILLIAM KENTON LANIER ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THE VIOLA MUSIC OF YORK BOWEN: LIONEL TERTIS, YORK BOWEN, AND THE RISE OF THE VIOLA IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY ENGLAND William Kenton Lanier, Candidate for the Master of Music Degree in Musicology University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT The viola owes its current reputation largely to the tireless efforts of Lionel Tertis (1876-1975), who, perhaps more than any other individual, brought the viola to light as a solo instrument. Prior to the twentieth century, numerous composers are known to have played the viola, and some even preferred it, but none possessed the drive or saw the necessity to establish it as an equal solo counterpart to the violin or cello. Likewise, no performer before Tertis had established themselves as a renowned exponent of the viola. Tertis made it his life’s work to bring the viola to the fore, and his musical prowess and technical ability on the instrument gave him the tools to succeed. Tertis was primarily a performer, thus collaboration with composers also comprised a necessary element of his viola crusade. He commissioned works from several British composers, including one of the first and most prolific composers for the viola, York Bowen (1884-1961).