Phd April 2019 Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

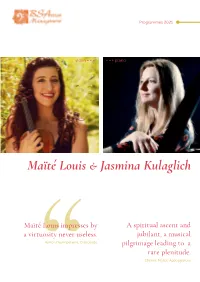

Maïté Louis & Jasmina Kulaglich

Programmes 2021 violin • • • • • • piano Maïté Louis & Jasmina Kulaglich Maïté Louis impresses by A spiritual ascent and a virtuosity never useless. jubilant, a musical Ayrton Desimpelaere, Crescendo pilgrimage leading to a rare plenitude. “ Etienne Muller, Appoggiature Biography Maïté Louis, violin An atypical personality in the world of classical This particularity of her career, this refusal to fit into music, Maïté Louis makes a lasting impression the prefabricated mould of soloists, this attach- with his overwhelming playing and extraordinary ment to finding music at the heart of everything, stage presence. make her the unique and rich artist she is today. Winner of numerous national and internation- al competitions (1st prize at the Golden Classical When Maïté Louis makes Music Awards in New York, 1st prize at the Interna- “ tional Grand Prize Virtuoso Competition in Rome, 2nd prize at the Glazounov International Compe- her violin cry, that’s all the tition, Silver Medal at the Ivo Pogorelich Interna- hall crying with her tional Competition in Manhattan, 3rd prize at the Le Dauphin Rising Star International Competition in Berlin, Prix d’Honneur de France Musique...), often praised by Some of these concerts: Berlioz Festival, Festival her peers, she divides her time between her ca- d’Auvers sur Oise, Grand Odéon in Paris, Festival reer as a soloist on the great classical stages and des Musiques Rares, Salle Cortot in Paris, Festival teaching at the Geneva Conservatory. Multirythmes, Bonlieu Scène Nationale d’Annecy, “Festival d’Evian, Festival Interceltique de Lorient, Her extreme virtuosity, combined with her ex- Festival Jeunes Talents, Palais des Congrès de traordinary expressiveness and musical sensitivity, Megève, Académie de Villecroze, Archipel Scène wonderfully serves the entire range of the great Nationale de Guadeloupe,.. -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

César Franck's Violin Sonata in a Major

Honors Program Honors Program Theses University of Puget Sound Year 2016 C´esarFranck's Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer's Influence on the Violin Repertory Clara Fuhrman University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/honors program theses/21 César Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major: The Significance of a Neglected Composer’s Influence on the Violin Repertory By Clara Fuhrman Maria Sampen, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements as a Coolidge Otis Chapman Scholar. University of Puget Sound, Honors Program Tacoma, Washington April 18, 2016 Fuhrman !2 Introduction and Presentation of My Argument My story of how I became inclined to write a thesis on Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major is both unique and essential to describe before I begin the bulk of my writing. After seeing the famously virtuosic violinist Augustin Hadelich and pianist Joyce Yang give an extremely emotional and perfected performance of Franck’s Violin Sonata in A Major at the Aspen Music Festival and School this past summer, I became addicted to the piece and listened to it every day for the rest of my time in Aspen. I always chose to listen to the same recording of Franck’s Violin Sonata by violinist Joshua Bell and pianist Jeremy Denk, in my opinion the highlight of their album entitled French Impressions, released in 2012. After about a month of listening to the same recording, I eventually became accustomed to every detail of their playing, and because I had just started learning the Sonata myself, attempted to emulate what I could remember from the recording. -

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

The Art of Music :A Comprehensive Ilbrar

1wmm H?mi BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT or Hetirg W, Sage 1891 A36:66^a, ' ?>/m7^7 9306 Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V.9 The art of music :a comprehensive ilbrar 3 1924 022 385 342 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385342 THE ART OF MUSIC The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia UniveTsity Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modem Music Society of New Yoric In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Lillian Nordica as Briinnhilde After a pholo from life THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME NINE The Opera Department Editor: CESAR SAERCHINGER Secretary Modern Music Society of New York Author, 'The Opera Since Wagner,' etc. Introduction by ALFRED HERTZ Conductor San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Formerly Conductor Metropolitan Opera House, New York NEW YORK THE NASTIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC i\.3(ft(fliji Copyright, 1918. by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Bights Reserved] THE OPERA INTRODUCTION The opera is a problem—a problem to the composer • and to the audience. The composer's problem has been in the course of solution for over three centuries and the problem of the audience is fresh with every per- formance. -

Pablo Ferrandez-Castro, Cello

Pablo Ferrández-Castro, Cello Awarded the coveted ICMA 2016 “Young Artist of the Year”, and prizewinner at the XV International Tchaikovsky Competition, Pablo Ferrández is praised by his authenticity and hailed by the critics as “one of the top cellists” (Rémy Louis, Diapason Magazine). He has appeared as a soloist with the Mariinsky Orchestra, Vienna Symphony Orchestra, St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Stuttgart Philharmonic, Kremerata Baltica, Helsinki Philharmonic, Tapiola Sinfonietta, Spanish National Orchestra, RTVE Orchestra, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, and collaborated with such artists as Zubin Mehta, Valery Gergiev, Yuri Temirkanov, Adam Fischer, Heinrich Schiff, Dennis Russell Davies, John Storgårds, Gidon Kremer, Ivry Gitlis and Anne-Sophie Mutter. Highlights of the 2016/17 season include his debut with BBC Philharmonic under Juanjo Mena, his debut at the Berliner Philharmonie with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, his collaboration with Christoph Eschenbach playing Schumann’s cello concerto with the HR- Sinfonieorchester and with the Spanish National Symphony, the return to Maggio Musicale Fiorentino under Zubin Mehta, recitals at the Mariinsky Theater and Schloss-Elmau, a European tour with Kremerata Baltica, appearances at the Verbier Festival, Jerusalem International Chamber Music Festival, Intonations Festival and Trans-Siberian Arts Festival, his debuts with Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale RAI, Barcelona Symphony Orchestra, Munich Symphony, Estonian National Symphony, Taipei Symphony Orchestra, Queensland Symphony Orchestra, and the performance of Brahms' double concerto with Anne-Sophie Mutter and the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Mr. Ferrández plays the Stradivarius “Lord Aylesford” (1696) thanks to the Nippon Music Foundation. . -

Aude Heurtematte Orgue

AUDE HEURTEMATTE ORGUE MARDI 20 OCTOBRE 2020 18H 30 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Passacaille et Thème fugué en ut mineur BWV 582 (14 minutes environ) CÉSAR FRANCK Choral n°1 en mi majeur (15 minutes environ) LOUIS VIERNE Troisième Symphonie en fa dièse mineur op. 28 : Adagio (7 minutes environ) FRANZ LISZT Fantaisie et fugue sur le choral « Ad nos, ad salutarem undam » S 259 (27 minutes environ) AUDE HEURTEMATTE orgue Ce concert sera diffusé ultérieurement sur France Musique. JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 1685-1750 illustration de la mission du Christ, quantité de motifs suggérant des références à divers chorals maintes fois traités par Bach. La Passacaille et Thème fugué : une œuvre non seulement d’une Passacaille et Thème fugué en ut mineur BWV 582 indicible beauté, pouvant se suffire à elle-même pour une première écoute, mais aussi, ce qui dans l’univers luthérien de Bach revêt une importance primordiale, un condensé de symbo- Première édition chez Dunst, éditeur à Francfort, en 1834. lique baroque à l’appui de la foi. Une telle œuvre, qui ne pouvait que fasciner la postérité, fut maintes fois adaptée : pour piano Si passacaille et chaconne, appellations quasiment interchangeables à l’époque, furent des (Eugen d’Albert), deux pianos (Max Reger) ou orchestre – Leopold Stokowski (qui était un formes abondamment utilisées dans toute l’Europe baroque – ainsi, sur le versant allemand, brillant organiste), Ottorino Respighi, René Leibowitz, Eugene Ormandy, Andrew Davis… par Buxtehude ou Pachelbel, dont Bach étudia les œuvres en profondeur – la Passacaille et C’est la version Respighi qui fut utilisée par Roland Petit pour son mimodrame en un acte, Thème fugué en ut mineur BWV 582 apparaît d’emblée hors normes, sans réel équivalent, conçu et écrit par Jean Cocteau, Le Jeune homme et la Mort (1946). -

The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes In

THE USE OF THE POLISH FOLK MUSIC ELEMENTS AND THE FANTASY ELEMENTS IN THE POLISH FANTASY ON ORIGINAL THEMES IN G-SHARP MINOR FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA OPUS 19 BY IGNACY JAN PADEREWSKI Yun Jung Choi, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Jeffrey Snider, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Choi, Yun Jung, The Use of the Polish Folk Music Elements and the Fantasy Elements in the Polish Fantasy on Original Themes in G-sharp Minor for Piano and Orchestra, Opus 19 by Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2007, 105 pp., 5 tables, 65 examples, references, 97 titles. The primary purpose of this study is to address performance issues in the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, by examining characteristics of Polish folk dances and how they are incorporated in this unique work by Paderewski. The study includes a comprehensive history of the fantasy in order to understand how Paderewski used various codified generic aspects of the solo piano fantasy, as well as those of the one-movement concerto introduced by nineteenth-century composers such as Weber and Liszt. Given that the Polish Fantasy, Op. 19, as well as most of Paderewski’s compositions, have been performed more frequently in the last twenty years, an analysis of the combination of the three characteristic aspects of the Polish Fantasy, Op.19 - Polish folk music, the generic rhetoric of a fantasy and the one- movement concerto - would aid scholars and performers alike in better understanding the composition’s engagement with various traditions and how best to make decisions about those traditions when approaching the work in a concert setting. -

4, 9 Et 12 OCTOBRE 2019

lislaeger O ©F. ©F. 4, 9 et 12 OCTOBRE 2019 20h IL ÉTAIT UNE FOIS LE GROUPE DES SIX En 1917, la création à Paris du ballet Parade de Jean Cocteau, sur une musique d’Erik Satie, des décors et costumes de Pablo Picasso, provoqua un scandale retentissant, et fournit à Apollinaire l’occasion de créer un mot qui fera fortune : « sur-réaliste ». Satie se vit alors entouré de jeunes compositeurs auxquels la guerre offrait une occasion de se débarrasser des grandes autorités musicales du passé, de Wagner à Debussy. Se retrouvant dans un atelier d’artistes de Montparnasse, le 6 juin 1917, pour leur premier concert en commun, Louis Durey, Georges Auric et Arthur Honegger formèrent ainsi autour de Satie les « Nouveaux Jeunes », aux- quels se joindront plus tard Germaine Tailleferre et Francis Poulenc. L’année suivante, Jean Cocteau transcrivit le fruit de conversations avec ces com- positeurs dans Le Coq et l’Arlequin, manifeste provocateur dédié à Auric. Fâché contre Durey, trop ravélien à son goût, Satie avait démissionné des « Nouveaux Jeunes », et Cocteau allait prendre les affaires en main. En 1919, Darius Milhaud rentra de son long séjour au Brésil, et participa le 5 avril de cette année au premier concert avec les cinq autres. Le 16 janvier 1920, dans un article de Comœdia intitulé « Un ouvrage de Rimsky et un ouvrage de Cocteau : les Cinq Russes, les Six Français et Erik Satie », le com- positeur et « musicographe » Henri Collet inventait une expression qui connaîtra un succès inattendu, « Le groupe des Six », faisant allusion au « groupe des Cinq » compositeurs jadis rassemblés pour un renouveau de la musique russe autour de Mily Balakirev, avec César Cui, Rimski-Korskakov, Moussorgski et Borodine. -

Fonds Charles Koechlin

Fonds Charles KOECHLIN Médiathèque Musicale Mahler 11 bis, rue Vézelay – F-75008 Paris – (+33) (0)1.53.89.09.10 Médiathèque Musicale Mahler – Fonds Charles Koechlin Table des matières Documents personnels sur Charles Koechlin .................................................................................. 4 Biographie / Ephémérides ........................................................................................................... 4 Ecrits autobiographiques ............................................................................................................. 4 Ecrits et dossiers de voyages ...................................................................................................... 5 Œuvres de Charles Koechlin ......................................................................................................... 10 Boite 1 : Listes d’œuvres ........................................................................................................... 10 Boite 2 : Ecrits de Ch. Koechlin sur ses œuvres ........................................................................ 10 Ecrits de Charles Koechlin ............................................................................................................ 12 Conférences .............................................................................................................................. 12 Causeries radiophoniques ......................................................................................................... 14 Articles et textes ....................................................................................................................... -

Rachael Dobosz Senior Recital

Thursday, May 11, 2017 • 9:00 p.m Rachael Dobosz Senior Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Thursday, May 11, 2017 • 9:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Rachael Dobosz, flute Senior Recital Beilin Han, piano Sofie Yang, violin Caleb Henry, viola Philip Lee, cello PROGRAM César Franck (1822-1890) Sonata for Flute and Piano Allegretto ben Moderato Allegro Ben Moderato: Recitativo- Fantasia Allegretto poco mosso Beilin Han, piano Lowell Liebermann (B. 1961) Sonata for Flute and Piano Op.23 Lento Presto Beilin Han, piano Intermission John La Montaine (1920-2013) Sonata for Piccolo and Piano Op.61 With driving force, not fast Sorrowing Searching Playful Beilin Han, piano Rachael Dobosz • May 11, 2017 Program Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Quartet in C Major, KV 285b Allegro Andantino, Theme and Variations Sofie Yang, violin Caleb Henry, viola Philip Lee, cello Rachael Dobosz is from the studio of Alyce Johnson. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Rachael Dobosz • May 11, 2017 Program notes PROGRAM NOTES César Franck (1822-1890) Sonata for Flute and Piano Duration: 30 minutes César Franck was a well known organist in Paris who taught at the Paris Conservatory and was appointed to the organist position at the Basilica of Sainte-Clotilde. From a young age, Franck showed promise as a great composer and was enrolled in the Paris Conservatory by his father where he studied with Anton Reicha. -

Symposium Records Cd 1156

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1156 The GREAT VIOLINISTS – Volume VII SHIN-ICHI SUZUKI GEORGE ENESCO JAQUES THIBAUD ZINO FRANCESCATTI At first glance there may appear to be little connection between the four composers on this disc other than their Gallicism, and even that may be disputed in the case of César Franck who was French only by adoption. Certainly there could hardly be a wider contrast of aims and ideals than between Franck, the priest of High Seriousness, and Ravel, the advocate of "le plaisir...d'une occupation inutile". Yet there are important, if unobvious, links. Franck and Fauré were the architects of the revival of French chamber music, and between them inspired what were to become the two main traditions of the late 19th/early 20th century. Chausson was a pupil of Franck, Ravel of Fauré. There is a link, too, in the dedications of two of the works. César Franck dedicated his Sonata to Eugène Ysaÿe as a wedding gift and, we are told, when it was presented to him at a banquet, so moved was he that he performed it, then and there. Chausson's Poème, too, is dedicated to Ysaÿe. After one run-through with piano and one rehearsal with orchestra he gave this piece too, its first performance. (One might add, on a more gruesome note, that both Franck and Chausson died as a result of vehicular accidents: Franck struck by the pole of a horse-omnibus, Chausson thrown over the handlebars of his bicycle.) The distinguished violinists on this disc between them have provided us with a recital of four masterworks from the French violin repertoire.