Moskaladoncm2012mmus.Pdf (1.531Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Rock with a European Twist: the Institutionalization of Rock’N’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20Th Century)❧

75 American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century)❧ Maria Kouvarou Universidad de Durham (Reino Unido). doi: dx.doi.org/10.7440/histcrit57.2015.05 Artículo recibido: 29 de septiembre de 2014 · Aprobado: 03 de febrero de 2015 · Modificado: 03 de marzo de 2015 Resumen: Este artículo evalúa las prácticas desarrolladas en Francia, Italia, Grecia y Alemania para adaptar la música rock’n’roll y acercarla más a sus propios estilos de música y normas societales, como se escucha en los primeros intentos de las respectivas industrias de música en crear sus propias versiones de él. El trabajo aborda estas prácticas, como instancias en los contextos francés, alemán, griego e italiano, de institucionalizar el rock’n’roll de acuerdo con sus propias posiciones frente a Estados Unidos, sus situaciones históricas y políticas y su pasado y presente cultural y musical. Palabras clave: Rock’n’roll, Europe, Guerra Fría, institucionalización, industria de música. American Rock with a European Twist: The Institutionalization of Rock’n’Roll in France, West Germany, Greece, and Italy (20th Century) Abstract: This paper assesses the practices developed in France, Italy, Greece, and Germany in order to accommodate rock’n’roll music and bring it closer to their own music styles and societal norms, as these are heard in the initial attempts of their music industries to create their own versions of it. The paper deals with these practices as instances of the French, German, Greek and Italian contexts to institutionalize rock’n’roll according to their positions regarding the USA, their historical and political situations, and their cultural and musical past and present. -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

Existing Songbook

Power Of Love - Lewis, The artist:Huey Lewis , writer:Huey Lewis, Chris Hayes, Johnny Colla https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ctAAx51gJCs [C] [Em] [F] [G] [C] [Em] [F] [G] [Cm7] [F] [Cm7] [F] [Bb] [F] The [Cm7] power of love is a [F] curious thing [Cm7] Make a one man weep, make a-[F] nother man sing [Cm7] Change a heart to a l[F] ittle white dove [Cm7] More than a feeling, [F] that's the power of love [Cm7] [F] [Bb] [F] [Cm7] Tougher than [F] diamonds, rich like cream [Cm7] Stronger and [F] harder than a bad girls dream [Cm7] Make a bad one [F] good, mmm make a wrong right [Cm7] Power of love will [F] keep you home at night [C] Don't need [Em] money, [F] don't take [G] fame [C] Don't need no [Em] credit [F] card to ride this [G] train [C] It's strong and it's [Em] sudden and it's [F] cruel some-[G] times But it [Bb] might just [F] save your [G] life That's the power of [Cm7] love [F] That's the [Cm7] power of love [F] [Bb] [F] [Cm7] First time you feel it [F] might make you sad [Cm7] Next time you feel it [F] might make you mad [Cm7] But you'll be glad baby [F] when you've found [Cm7] That's the power that makes [F] the world go round [C] Don't need [Em] money, [F] don't take [G] fame [C] Don't need no [Em] credit [F] card to ride this [G] train [C] It's strong and it's [Em] sudden and it's [F] cruel some-[G] times But it [Bb] might just [F] save your [G] life [Eb] They say that [G] all in love is [Cm] fair, yeah but [Fm] you don't care [Ab] But you know [Gm7] what to do, [Fm] when it gets [Gm7] hold of you [Ab] And with a little [G] help -

2012-Fall.Pdf

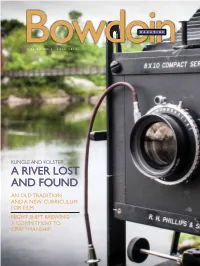

MAGAZINE BowdoiVOL.84 NO.1 FALL 2012 n KLINGLE AND KOLSTER A RIVER LOST AND FOUND AN OLD TRADITION AND A NEW CURRICULUM FOR FILM NIGHT SHIFT BREWING: A COMMITMENT TO CRAFTMANSHIP FALL 2012 BowdoinMAGAZINE CONTENTS 14 A River Lost and Found BY EDGAR ALLEN BEEM PHOTOGRAPHS BY BRIAN WEDGE ’97 AND MIKE KOLSTER Ed Beem talks to Professors Klingle and Kolster about their collaborative multimedia project telling the story of the Androscoggin River through photographs, oral histories, archival research, video, and creative writing. 24 Speaking the Language of Film "9,)3!7%3%,s0(/4/'2!0(3"9-)#(%,%34!0,%4/. An old tradition and a new curriculum combine to create an environment for film studies to flourish at Bowdoin. 32 Working the Night Shift "9)!.!,$2)#(s0(/4/'2!0(3"90!40)!3%#+) After careful research, many a long night brewing batches of beer, and with a last leap of faith, Rob Burns ’07, Michael Oxton ’07, and their business partner Mike O’Mara, have themselves a brewery. DEPARTMENTS Bookshelf 3 Class News 41 Mailbox 6 Weddings 78 Bowdoinsider 10 Obituaries 91 Alumnotes 40 Whispering Pines 124 [email protected] 1 |letter| Bowdoin FROM THE EDITOR MAGAZINE Happy Accidents Volume 84, Number 1 I live in Topsham, on the bank of the Androscoggin River. Our property is a Fall 2012 long and narrow lot that stretches from the road down the hill to our house, MAGAZINE STAFF then further down the hill, through a low area that often floods when the tide is Editor high, all the way to the water. -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

Vitality 'Wet'

The Retriever, December 4, 1979, Pase 9 Knack c ' aptur~sBeatle sound, vitality By Julie Thompson that the emphasis on teenage love prevalent ill the early 1960's has shifted to Since their success in the Los Angeles one on teenage sex. With its seductive, club circuit in 1978,IThe Knack has set the pounding beat and blunt lyrics, "Selfish" musical world on its ear. The four is but a segment of the thematic thread musicianr" Doug Fieger, Berton Verre, running throughout the disc including Bruce Gap , and Prescott Niles, have such cuts as "Frustrated" and "Good Girls indeed been compared time and again with Don't." the 'Beatles, and justifiably so considering their concert stop at Carnegie Hall in New Although infectious, racey beal and York last month. The concert created a fervor quite reminiscent of those early, clamorous vocals seem to be the Knack's , heady days of Beatlemania, Get the Knack, speciality, the group proves themselves their debut album, only further warrants masters also of a more subdued style in "Maybe Tonight," the only mellow cut of the call for enthusiasm over this newly formed quartet. In their attempt to reinsti the album. Fieger's voice artfully weaves throughout this lazily tuneful track, tute the values brought to rock and roll by peaking with the refraining crescendo and the Beades, The Knack has produced an sliding easily back to an idle momentum. album brimmin~ with vitality. Aside from "My Sharona" and "Good Considering the success of this first Girls ,Don't," the two renown singles album, no doubt the music-enthusiastic released to date, Gel the Knack harbors a public, in hopes of unraveling the mystery collection of cuts that could each undoubt of the Knack phenomenom, is waiting , "{he Knack edly attain number one status as singles, with bated breath for a second release. -

Twentieth Century UK and US Popular Music History (Things You May Not Have Known Or Never Thought to Ask)

2020 Series 3 Course H Title Twentieth Century UK and US Popular Music History (things you may not have known or never thought to ask) Dates Fridays 16 October – 20 November 2020 Time 10 am – 12 noon Venue Leith Bowling Club, 2 Duke Street, North Dunedin Convenors Linda Kinniburgh & Pat Thwaites Email: [email protected] Phone: 473 8443 Mobile: 021 735 614 Developer Rob Burns Course fee $45 Bank account U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust 06 0911 0194029 00 This course provides a historical insider’s view of how modern popular music evolved from a relatively amateur business on both sides of the Atlantic in the late nineteenth century, into a contemporary billion dollar industry driven by constant change and reworking of pre-existing styles. It also addresses how technology has played a major role in musical development and change during the twentieth century. All presenters are from the School of Performing Arts, University of Otago. All applications must be received by Thursday 17 September 2020. You will receive a response to your application by Monday 28 Septembert 2020. Please contact the Programme Secretary [email protected], phone 467 2594 with any queries. U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust u3adunedin.org.nz Twentieth Century UK and US Popular Music History 16 October Changes in popular music and technology as pop music enters the twentieth century -Associate Professor Robert Burns Invention of recording technologies, changes to copyright and publishing laws, family entertainment, changes to listening trends caused by WWI – with the introduction of Vaudeville and the necessary changes to old Music Hall, and folk music in the middle! 23 October The jazz age in the UK, France and the US: The Blues, Bessie, Basie, Billie, Bechet, Ella and Ellington -Associate Professor Peter Adams Big Band Jazz, the major artists of the 1920s and 1930s and their effect on allied morale in WW2. -

The Comment, September 24, 1987

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University The ommeC nt Campus Journals and Publications 1987 The ommeC nt, September 24, 1987 Bridgewater State College Volume 65 Number 1 Recommended Citation Bridgewater State College. (1987). The Comment, September 24, 1987. 65(1). Retrieved from: http://vc.bridgew.edu/comment/603 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Comment Bridgewater State College September 24, 1987 Vol. LXV No. 1 Bridgewater, MA Changes are in store for next year's freshman applicants By Chris Perra in which a student can apply. two years, this cap on admissions The College will inform students will be continued in an effort to Students applying to of acceptance or rejection between reduct the student to faculty ratio. Bridgewater next year will April 1 and April 15; the student, As it stands now, the ratio is encounter a system very different in turn. must notify the College approximately 23: 1. The ideal from the one present students as to his intention by May 1. In ratio that is being worked towards met. order to give a student a chance to is 17:1. Prospective students will express him or herself in works, have to submit a writing sample separate from their academic President Indelicato stated that ·in addition to their application. credentials, the College will is was the administration's hope This essay ,on an as yet undecided institute a system for that the . admissions topic, will be reviewed by the administering voluntary competitiveness level will be admissions office. -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Talento Sharona

Talento Sharona THE KNACK: IL FENOMENO “SHARONA” THE KNACK, “IL TALENTO”: questo è il nome della band di Los Angeles capitanata da Doug Fieger (chitarra e voce) e Berton Averre (chitarra) che ha segnato il mondo della musica a partire dalla fine degli anni settanta! A completare il quartettoPrescott Niles (basso) e Bruce Gary (batteria). Una delle band meno prolifiche del panorama Rock, ma sicuramente tra le più incisive. Una sola canzone che ha reso THE KNACK immortali: My Sharona! Con questo capolavoro THE KNACK del compianto Fieger (Doug Fieger è morto nel 2010 all’età di 57 anni per un tumore cerebrale; n.d.a.) hanno scalato le vette delle classifiche di quasi tutti i paesi del mondo rimanendoci fino ai giorni nostri. My Sharona è infatti la canzone più ascoltata da intere generazioni. Sono disposto a sfidare chiunque abbia più di 12 anni a non conoscere questo simbolo del Rock targato anni settanta… ottanta, novanta, duemila, duemilaedieci e pure venti! Moltissimi sono i musicisti che hanno adorato le canzoni di Doug & Co. ed alcuni hanno continuato a suonare la cover di My Sharona nei loro concerti, ricordo solo questi mostri sacri del Rock: METALLICA, FOO FIGHTERS, NIRVANA e ci metto pure i TIMORIA dell’amico Omar Pedrini. THE KNACK sono stati spesso sottovalutati, nonostante abbiano prodotto pezzi di grandissimo valore come Good Girls Don’t e Baby Talks Dirty. Solo My Sharona però ha tributato al Combo californiano un successo strabiliante. Il riff iniziale è uno dei più celebri e riconoscibili del Rock, forse anche più famoso dell’intro di Smoke on the Water dei DEEP PURPLE. -

Lanthorn, Vol. 12, No. 14, November 15, 1979 Grand Valley State University

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Volume 12 Lanthorn, 1968-2001 11-15-1979 Lanthorn, vol. 12, no. 14, November 15, 1979 Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lanthorn_vol12 Part of the Archival Science Commons, Education Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Grand Valley State University, "Lanthorn, vol. 12, no. 14, November 15, 1979" (1979). Volume 12. 14. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lanthorn_vol12/14 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Lanthorn, 1968-2001 at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 12 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Grand Valley's Student Run Weekly he Lanthorn Number 12 Volume 12 ALLENDALE, THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 1979 Student Senate Refuses Request; WIB Has No Funds for Staff Warming up for the Zumberge Fol- lies? Nope, just rushing to clati. In The Student Senate Friday re dent Senate gave then $2,500. what the phone number is, and cidentally, the thought our photog fused a request from the Women’s Hubbard said the exception to the things like that." rapher was "crazy" for taking her Information Bureau (WIB) for an ex wage rule was denied because “by No decision was made pending in picture (photo by John Haafkel. ception to the rule which forbids use the time we got the (Student Senate) vestigation of the availability of of student activities fees for student constitution changed, it would be grant money. wages. winter term.” The senate also discussed the The senate also discussed hiring a Hubbard said that the Senate radio task force which is studying public relations officer for itself, and would try to support WIB in other WSRX and the possibility of getting heard a report on the radio task ways by searching for funds outside a national public radio on campus. -

The Cord Weekly (November 16, 1978)

Thursday, November 16, 1978 tt,e ~rd Wee~ly Volume 19, Number 9 WLU Press acquires new equipment• bv Carl Friesen has to date published 41 books Last Thursday, WLU Press all priced at $10.00 or less, as held an open house to demon well as 3 journals. According to strate some of its new equip· Harold Remus, Director of WLU ment. This equipment brings the Press, sales are up 75% during Press well up to modern stan· the past year. Some titles are dards in electronic printing now out of print, but all are technology. Now, a computer available on microfiche. console almost anywhere in the As the system works now, the world can be used to programme manuscript is typed on a com· the Press to print a variety of puter console, and the in print types and sizes. Much of formation is translated into tape the credit for the private format, which is then fed into the ingenuity and work goes to Dr. type machine. Here, the line Hart Bezner, director of the com length, type size, and print style puter centre, and his staff. in the final copy are selected, and Since. its beginning in 1974, a sheet of print the size of the WLU Press has done its best to final copy is produced. This is print scholarly works in small photographed, and the negative volume at low cost, with no frills. used in the final paste-up, which Because commercial publishers is done by himd. The actual prin are only willing to print books ting is done by other presses, and journals with large print generally out of town.