Murphree-Framing a Disaster.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oklahoma Today February 2002 Volume 52 No. 2: the Year In

OKLAHO FEBRUARY 2002 Today \LAWMAN OF THE YEAR -.. ....__ --- --.__ FALLEN COWBOYS VEIGH: A FINAL CHAPTER Where there's Williams, there's a From building sidewalks in 1908, For nearly a century, to now -building energy pipelines coast-to-coast, our Oklahoma roots building strong relationships every place we call have served us well, home -where there's Williams, there's a way. and helped us serve ourI neighbors and neighborhoods A way to be more than a company- a way to be even better. Though it may sound clichkd, we think a vital part of our community. A way to better our the Williams way of integrity and reliability will be surroundings and ourselves. just as important in our next century. Williams people possessthe powers of ilnaginationand deternrinath, plus a desire to accomplish something significant. That's why we succeed -in our industry and our communities. It's just our way. LeadingEnergy Sdutions, (800)Williams NYSE:WMB williams.com energynewslive.com Route -7 --1 i -- -- -. ,' * I ' The Performance Company Where you will always find good things-- for cars and the people who drive them.TM Q CoWrigM Phillips Petroleum Company, 2MH). 4122-00 THE YEAR IN REVIEW LOUISA MCCUNE Editor in Chicf An Dirmr: STEVEN WALKER, WALKER CREATIVE, INC.; Senior Edimc STEFFIE CORCORAN Auociate EdiMc ANDREA LOPEZ WALKER; Edimdhir*ln&: BROOKE DEMETZ and RYAN MARIE MENDENHW; Editorial Inm: HEATHER SUGRUE;AdvmirngDin&c WALT DISNEY; Account &cutivc~: CHARLOTTE ASHWORTH &KIM RYAN; Advmirng InmSHARON WALKER; hd~cffbnManager: COLLEEN MCINTYRE; Adv&ng GraphicA&: SAND1 WELCH General Manager: MELANIE BREEDEN; Accounrant: LISA BRECKENRIDGE Ofit Manap BECKY ISAAC; @ccAahnt: KATHY FUGATE JOAN HENDERSON Publisher JANE JAYROE, Ewccutiue Dircmr Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Dqamt Toutinn and Recreation Cmnrnish LT. -

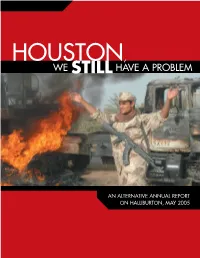

Houston, We Still Have a Problem

HOUSTON, WE STILL HAVE A PROBLEM AN ALTERNATIVE ANNUAL REPORT ON HALLIBURTON, MAY 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION II. MILITARY CONTRACTS III. OIL & GAS CONTRACTS IV. ONGOING INVESTIGATIONS AGAINST HALLIBURTON V. CORPORATE WELFARE & POLITICAL CONNECTIONS VI. CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS COVER: An Iraqi National Guard stands next to a burning US Army supply truck in the outskirts of Balad, Iraq. October 14, 2004. Photo by Asaad Muhsin, Associated Press HOUSTON, WE HAVE A PROBLEM HOUSTON, WE STILL HAVE A PROBLEM In the introduction to Halliburton’s 2004 annual report, chief executive officer David Lesar reports to Halliburton’s shareholders that despite the extreme adversity of 2004, including asbestos claims, dangerous work in Iraq, and the negative attention that sur- rounded the company during the U.S. presidential campaign, Halliburton emerged “stronger than ever.” Revenue and operating income have increased, and over a third of that revenue, an estimated $7.1 billion, was from U.S. government contracts in Iraq. In a photo alongside Lesar’s letter to the shareholders, he From the seat of the company’s legal representatives, the view smiles from a plush chair in what looks like a comfortable is of stacks of paperwork piling up as investigator after investi- office. He ends the letter, “From my seat, I like what I see.” gator demands documents from Halliburton regarding every- thing from possible bribery in Nigeria to over-billing and kick- People sitting in other seats, in Halliburton’s workplaces backs in Iraq. The company is currently being pursued by the around the world, lend a different view of the company, which continues to be one of the most controversial corporations in U.S. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Congressional Record—House H9187

October 2, 2003 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H9187 Once private insurance companies have in- There was no objection. www.newbridgestrategies.com, says, ‘‘The opportunities evolving in Iraq today are of come data on seniors, they can use it to se- f lectively market their products to higher in- such an unprecedented nature and scope that DISPENSING WITH CALENDAR no other existing firm has the necessary come seniors, who are likely to be healthier skills and experience to be effective both in and use less health services. WEDNESDAY BUSINESS ON Washington, D.C., and on the ground in This is a recipe for disaster. It is a step in WEDNESDAY NEXT Iraq.’’ the wrong direction for the successful and effi- Mr. FLAKE. Madam Speaker, I ask The site calls attention to the links be- cient Medicare program, that up until now has unanimous consent that the business tween the company’s directors and the two Bush administrations by noting, for exam- served every senior equally well. The ap- in order under the Calendar Wednesday proach taken in the Republican bill is wrong. ple, that Mr. Allbaugh, the chairman, was rule be dispensed with on Wednesday ‘‘chief of staff to then-Gov. Bush of Texas We should not be taxing middle-class seniors next. and was the national campaign manager for twice for their Medicare benefits. The SPEAKER pro tempore. Is there the Bush-Cheney 2000 presidential cam- We should eliminate the means testing of objection to the request of the gen- paign.’’ catastrophic drug coverage in the House Re- tleman from Arizona? The president of the company, John publican bill. -

The Candidates

The Candidates Family Background Bush Gore Career Highlights Bush Gore Personality and Character Bush Gore Political Communication Lab., Stanford University Family Background USA Today June 15, 2000; Page 1A Not in Their Fathers' Images Bush, Gore Apply Lessons Learned From Losses By SUSAN PAGE WASHINGTON -- George W. Bush and Al Gore share a reverence for their famous fathers, one a former president who led the Gulf War, the other a three-term Southern senator who fought for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. The presidential candidates share something else: a determination to avoid missteps that brought both fathers repudiation at the polls in their final elections. The younger Bush's insistence on relying on a trio of longtime and intensely loyal aides -- despite grumbling by GOP insiders that the group is too insular -- reflects his outrage at what he saw as disloyalty during President Bush's re-election campaign in 1992. He complained that high- powered staffers were putting their own agendas first, friends and associates say. Some of those close to the younger Gore trace his willingness to go on the attack to lessons he learned from the above-the-fray stance that his father took in 1970. Then-senator Albert Gore Sr., D-Tenn., refused to dignify what he saw as scurrilous attacks on his character with a response. The approach of Father's Day on Sunday underscores the historic nature of this campaign, as two sons of accomplished politicians face one Political Communication Lab., Stanford University another. Their contest reveals not only the candidates' personalities and priorities but also the influences of watching their famous fathers, both in victory and in defeat. -

Publication 1

We Are FEMA Helping People Before, During, and After Disasters 2 Publication 1 Purpose Publication 1 (Pub 1) is our capstone doctrine. It helps us as Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) employees understand our role in the emergency management community and provides direction for how we conduct ourselves and make decisions each day. It explains: ▪ Who We Are: An understanding of our identity and foundational beliefs ▪ Why We Are Here: A story of pivotal moments in history that have built and shaped our Agency ▪ What We Face: How we manage unpredictable and ever-evolving threats and hazards ▪ What We Do: An explanation of how we help people before, during, and after disasters ▪ How We Do It: An understanding of the principles that guide the work we do The intent of our Pub 1 is to promote innovation, flexibility, and performance in We Are FEMA achieving our mission. It promotes unity of purpose, guides professional judgment, and enables each of us to fulfill our responsibilities. Audience This document is for every FEMA employee. Whether you have just joined us or have been with the Agency for many years, this document serves to remind us why we all choose to be a part of the FEMA family. Our organization includes many different offices, programs, and roles that are all committed to helping people. Everyone plays a role in achieving our mission. We also invite and welcome the whole community to read Pub 1 to help individuals and organizations across the Nation better understand FEMA’s mission and role as we work together to carry out an effective system of emergency management. -

Profiles of 12 Companies That Have Received Large Contracts for Cleanup and Reconstruction Work Related to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita

Profiles of 12 companies that have received large contracts for cleanup and reconstruction work related to Hurricanes Katrina and Rita Prepared for Interfaith Worker Justice by Philip Mattera Research Director of Good Jobs First and Director of its Corporate Research Project (incorporating material on Bechtel, Fluor and Halliburton contractor misconduct prepared by the Project On Government Oversight) Revised March 2006 Corporate Research Project / Good Jobs First 1616 P Street NW Suite 210 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 232-1616 • fax (202) 232-6680 www.corp-research.org • www.goodjobsfirst.org This research was funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. We thank them for their support but acknowledge that the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the author(s) alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation. 2 SUMMARY This report reviews the track record of 12 companies that have received the largest contracts for cleanup and reconstruction work in the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. It focuses on those contracts that involved work that would be performed in the area affected by the storms and excludes those that involved bringing in goods manufactured elsewhere in the country. The 12 companies are: AshBritt Inc. Bechtel Group Inc. Ceres Environmental Clearbrook LLC D&J Enterprises ECC (Environmental Chemical Corp.) Fluor Corporation IAP Worldwide Services Inc. Kellogg, Brown & Root, a subsidiary of Halliburton Company LJC Construction (also known as LJC Defense Contracting) Phillips and Jordan Inc. The Shaw Group Inc. The first thing to point out is that these companies vary enormously in size and influence. -

The Past Several Months Has Seen Increased Attention and Publicity

BRITISH AMERICAN SECURITY INFORMATION COUNCIL BASIC RESEARCH REPORT A Fistful of Contractors: The Case for a Pragmatic Assessment of Private Military Companies in Iraq By David Isenberg Research Report 2004.4 September 2004 British-American Security Information Council The British-American Security Information Council is an independent research organization that analyzes international security issues. BASIC works to promote awareness of security issues among the public, policy makers and the media in order to foster informed debate on both sides of the Atlantic. BASIC in the UK is a registered charity no. 1001081. BASIC in the US a non-profit organization constituted under Section 501 (c)(3) of the US Internal Revenue Service Code. Published by the British American Security Information Council BASIC Research Report 2004.4 – September 2004 Author David Isenberg has been researching and writing on private military companies for over a decade. His 1997 monograph "Soldiers of Fortune Ltd.: A Profile of Today's Private Sector Corporate Mercenary Firms" and television episode "Conflict Inc." are acknowledged staples in the field. He has written on the subject for the Christian Science Monitor, USA Today magazine, IntellectualCapitol, and Asia Times; lectured at US military schools and overseas on the subject; and been a frequent commentator on numerous radio and television shows on PMC activities. Acknowledgements The writing of this report would not have been possible without the information and comments made on the AMPM list (http://groups.yahoo.com/group/AMPMlist), devoted to the international trade in private military services run by Doug Brooks, founder of the International Peace Operations Association. -

Reputation and Federal Emergency Preparedness Agencies, 1948-2003

Reputation and Federal Emergency Preparedness Agencies, 1948-2003 Patrick S. Roberts Department of Politics University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 22903 [email protected] Comments welcome. Prepared for Delivery at the 2004 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, September 2-5, 2004. Copyright by the American Political Science Association. Abstract What caused the Federal Emergency Management Agency to go from being threatened with extinction to becoming one of the most popular agencies in government? FEMA developed a reputation both for anticipating the needs of politicians and the public and for efficiently satisfying those needs. I locate the root of reputation for a contemporary agency in a connection to a profession which helps hone a few core tasks and a single mission, in the development of a bureaucratic entrepreneur, and, finally, in a connection to the president, Congress, and the public. Reputation and Federal Emergency Preparedness Agencies, 1948-2003 1 The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 led Congress and the president to undertake one of the most ambitious reorganizations in American history to respond to the now undeniable threat of domestic terrorism.1 The creation of the Department of Homeland Security sparked dramatic changes in several agencies included in the new department: the Customs and Border Patrol agencies were consolidated and then separated, the Coast Guard began building a deep water capability, and the FBI shifted resources from drug crimes to counterterrorism.2 Some political -

Vicepræsidentposten I Amerikansk Politik Mads Fuglede

Vicepræsidentposten i amerikansk politik Mads Fuglede Med John McCains valg af Sarah Palin er vicepræ - sidentposten kommet på alles læber. Men hvor vigtig er den post egentlig? Havde Benjamin Franklin ret, da han giftigt foreslog, at man skulle tiltale vicepræsidenten med: ‘Deres overflødig- hed?’ Her følger et historisk tilbageblik Tidligt i 2000, mens George W. Bush sidigt. Desuden forbød den ameri- kæmpede indædt mod John McCain kanske forfatning med sin 12. til - om sit partis nomination, fløj Joe føjelse, at to kandidater, der var bor- All baugh til Dallas for at mødes med gere i samme stat, stillede op sam- Richard Cheney. men. Joe Allbaugh var kampagneleder Joe Allbaugh fløj tilbage til Austin, for Bush og var i gang med at forbe- Texas, med uforrettet sag. Det inte - rede en liste over mulige vicepræsi- ressante ved samtalen er, at Cheneys dentkandidater. Ifølge journalisten argumenter var så dårlige, at de ikke Robert Draper spurgte Allbaugh, kan have været den egentlige be- om Cheney kunne tænke sig at være væggrund bag afvisningen. Det er Bushs vicepræsident, men fik det mere sandsynligt, at Cheney vidste, svar, at det ville være en dårlig idé af at det embede, han blev tilbudt, to grunde: Begge havde en bag- ikke var særligt eftertragtet. grund i olieindustrien (Cheney var Richard Cheney havde været tæt på det tidspunkt administrerende på magten før, som stabschef (1975- direktør for Halliburton, og Bush 77) for præsident Gerald Ford og havde stiftet olieselskabet Arbusto forsvarsminister (1989-93) for præsi- Energy tilbage i 1977), hvilket ville dent George H. W. Bush, og vidste, få deres kandidatur til at fremstå en- at vicepræsidentembedet var usæd- udenrigs 3·2008 43 TEMA: USA’S VALG vanligt vanskeligt at bestride og ho- spurgte, om han ikke ville være be- vedsagligt var underlagt præsiden- hjælpelig med at finde en vicepræsi- tens luner. -

Dominion Issue #32.Indd

dominion, n. 1. Control or the exercise of control. 2. A territory or sphere of infl uence; a realm. 3. One of the self-governing nations within the British Commonwealth. The Dominion CANADA’S GRASSROOTS NEWSPAPER WWW.DOMINIONPAPER.CA • DECEMBER, 2005 • Vol. II, #14 Privatization in BC Reconstructing Disaster A New University Unions and government face Corporations and post-Katrina Ecology and social justice off once again. rebuilding contracts. frame founding meeting. » p. 2 » p. 8 » p. 13 $0 to $5 Sliding scale Independent Journalism depends on independent people. Please subscribe. dominionpaper.ca/subscribe The Dominion, December 2005 • Vol. II, #14 Canadian News 2 Beautiful—Privatized—British Columbia? Health care workers, teachers, fight government over policy by Dru Oja Jay private schools. Dr. Ernie Lightman, a pro- When British Columbia’s fessor in Social Work at the Uni- teachers defied laws passed by versity of Toronto and former Gordon Campbell’s Liberals to faculty member of the London stage an “illegal strike” in Octo- School of Economics, called the ber, it was the second major tactics used in BC “very analo- showdown with organized gous to what Margaret Thatcher labour since the Liberals took did in Britain.” power in 2001. The health care “If you’re going to do some- workers’ strike in April 2004 thing the other guy doesn’t had seen 43,000 workers in 11 want done, you beat up on his unions join picket lines. symbol,” said Lightman. In The Liberal government Thatcher’s case, “Privatiza- imposed contracts on health tion was a way of wrecking the care workers and teachers, unions.” bypassing collective bargaining Lightman, who has stud- and arbitration by legislating ied the tenure of Mike Harris’ their terms directly. -

The Historical Context of Emergency Management

1 The Historical Context of Emergency Management What You Will Learn • The early roots of emergency management. • The modern history of emergency management in the United States. • How FEMA came to exist, and how it evolved during the 1980s, 1990s, and the early twenty-first century. • The sudden changes to modern emergency management that have resulted from the September 11 terrorist attacks and Hurricane Katrina. Introduction Emergency management has ancient roots. Early hieroglyphics depict cavemen trying to deal with disasters. The Bible speaks of the many disasters that befell civilizations. In fact, the account of Moses parting the Red Sea could be interpreted as the first attempt at flood control. As long as there have been disasters, individuals and communities have tried to do something about them; however, organized attempts at dealing with disasters did not occur until much later in modern history. The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the cultural, organizational, and leg- islative history of modern emergency management in the United States. Some of the significant events and people that shaped the emergency management discipline over the years are reviewed. Understanding the history and evolution of emergency man- agement is important because, at different times, the concepts of emergency manage- ment have been applied differently. The definition of emergency management can be extremely broad and all-encompassing. Unlike other more structured disciplines, it has expanded and contracted in response to events, congressional desires, and leadership styles. In the most recent history, events and leadership, more than anything else, have brought about dramatic changes to emergency management in the United States.