Country Profile 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

Change 3, FAA Order 7340.2A Contractions

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION 7340.2A CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2A, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all international aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to the interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. July 29, 2010. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Changes, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. Y[fa\.Uj-Koef p^/2, Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: k/^///V/<+///0 Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-464 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 7/29/10 JO 7340.2A CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 4/8/10 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−2 . 7/29/10 1−1−1 . 8/27/09 1−1−1 . 7/29/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 4/8/10 2−1−23 through 2−1−27 . 7/29/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−28 . 4/8/10 2−2−23 . -

Die Folgende Liste Zeigt Alle Fluggesellschaften, Die Über Den Flugvergleich Von Verivox Buchbar Sein Können

Die folgende Liste zeigt alle Fluggesellschaften, die über den Flugvergleich von Verivox buchbar sein können. Aufgrund von laufenden Updates einzelner Tarife, technischen Problemen oder eingeschränkten Verfügbarkeiten kann es vorkommen, dass einzelne Airlines oder Tarife nicht berechnet oder angezeigt werden können. 1 Adria Airways 2 Aegean Airlines 3 Aer Arann 4 Aer Lingus 5 Aeroflot 6 Aerolan 7 Aerolíneas Argentinas 8 Aeroméxico 9 Air Algérie 10 Air Astana 11 Air Austral 12 Air Baltic 13 Air Berlin 14 Air Botswana 15 Air Canada 16 Air Caraibes 17 Air China 18 Air Corsica 19 Air Dolomiti 20 Air Europa 21 Air France 22 Air Guinee Express 23 Air India 24 Air Jamaica 25 Air Madagascar 26 Air Malta 27 Air Mauritius 28 Air Moldova 29 Air Namibia 30 Air New Zealand 31 Air One 32 Air Serbia 33 Air Transat 34 Air Asia 35 Alaska Airlines 36 Alitalia 37 All Nippon Airways 38 American Airlines 39 Arkefly 40 Arkia Israel Airlines 41 Asiana Airlines 42 Atlasglobal 43 Austrian Airlines 44 Avianca 45 B&H Airlines 46 Bahamasair 47 Bangkok Airways 48 Belair Airlines 49 Belavia Belarusian Airlines 50 Binter Canarias 51 Blue1 52 British Airways 53 British Midland International 54 Brussels Airlines 55 Bulgaria Air 56 Caribbean Airlines 57 Carpatair 58 Cathay Pacific 59 China Airlines 60 China Eastern 61 China Southern Airlines 62 Cimber Sterling 63 Condor 64 Continental Airlines 65 Corsair International 66 Croatia Airlines 67 Cubana de Aviacion 68 Cyprus Airways 69 Czech Airlines 70 Darwin Airline 71 Delta Airlines 72 Dragonair 73 EasyJet 74 EgyptAir 75 -

MAHB05 01 Strong Heritage

11 Financial stability financial statements ’05 126 Directors’ Report 130 Statement by Directors 130 Statutory Declaration 131 Report of the Auditors 132 Consolidated Income Statement 133 Consolidated Balance Sheet 134 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 135 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 137 Income Statement 138 Balance Sheet 139 Statement of Changes in Equity 140 Cash Flow Statement 142 Notes to the Financial Statements Directors’ Report The directors have pleasure in presenting their report together with the audited financial statements of the Group and of the Company for the financial year ended 31 December 2005. PRINCIPAL ACTIVITIES The principal activity of the Company is investment holding. The principal activities of the subsidiaries are disclosed in Note 12 to the financial statements. There have been no significant changes in the nature of the principal activities during the financial year. RESULTS Group Company RM’000 RM’000 Net profit for the year 182,263 62,846 There were no material transfers to or from reserves or provisions during the year other than as disclosed in the financial statements. In the opinion of the directors, the results of the operations of the Group and of the Company during the financial year were not substantially affected by any item, transaction or event of a material and unusual nature. DIVIDENDS The amount of dividend declared and paid by the Company since 31 December 2004 was as follows: RM’000 In respect of the financial year ended 31 December 2004 as reported in the directors’ report of that year: Final dividend of 3% less 28% taxation, paid on 17 June 2005 23,760 At the forthcoming Annual General Meeting, a final dividend in respect of the financial year ended 31 December 2005, of 4% less 28% taxation on 1,100,000,000 ordinary shares, amounting to RM31,680,000 (2.88 sen net per share) will be proposed for shareholders’ approval. -

Nepal Abroad.Pmd

Nepal Abroad Published weekly from Washington D.C. Nepal Abroad Saturday Shrawan 12, 2064 B.S. / July 28, 2007 Year 2. No. 28 Little Lady Talent Show Hundreds Displaced By 12345678901234567890123456789012123452007, Nepal Violence In Southeast 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 Kathmandu, July 25 (IRIN) - southeast at the hands of 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 Hariram Joshi is too scared to groups demanding greater 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 reveal where he is hiding in political rights and regional 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 123 the Nepali capital, autonomy for the Madhesi 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 Kathmandu, after fleeing his community in the Terai. 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 home last week in Siraha Dis- Local non-govern- 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 trict, nearly 400km southeast mental organisations (NGOs), 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 of Kathmandu. He had re- the UN, and aid agencies 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 ceived death threats from al- working with internally dis- 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 leged members of Janatantrik placed persons (IDPs) have 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 Terai Mukti Morcha (JTMM), expressed concern over the 1234567890123456789012345678901212345 one of the most feared mili- newly displaced -

ROJ BAHADUR KC DHAPASI 2 Kamalapokhari Branch ABS EN

S. No. Branch Account Name Address 1 Kamalapokhari Branch MANAHARI K.C/ ROJ BAHADUR K.C DHAPASI 2 Kamalapokhari Branch A.B.S. ENTERPRISES MALIGAON 3 Kamalapokhari Branch A.M.TULADHAR AND SONS P. LTD. GYANESHWAR 4 Kamalapokhari Branch AAA INTERNATIONAL SUNDHARA TAHAGALLI 5 Kamalapokhari Branch AABHASH RAI/ KRISHNA MAYA RAI RAUT TOLE 6 Kamalapokhari Branch AASH BAHADUR GURUNG BAGESHWORI 7 Kamalapokhari Branch ABC PLACEMENTS (P) LTD DHAPASI 8 Kamalapokhari Branch ABHIBRIDDHI INVESTMENT PVT LTD NAXAL 9 Kamalapokhari Branch ABIN SINGH SUWAL/AJAY SINGH SUWAL LAMPATI 10 Kamalapokhari Branch ABINASH BOHARA DEVKOTA CHOWK 11 Kamalapokhari Branch ABINASH UPRETI GOTHATAR 12 Kamalapokhari Branch ABISHEK NEUPANE NANGIN 13 Kamalapokhari Branch ABISHEK SHRESTHA/ BISHNU SHRESTHA BALKHU 14 Kamalapokhari Branch ACHUT RAM KC CHABAHILL 15 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTION FOR POVERTY ALLEVIATION TRUST GAHANA POKHARI 16 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTIV NEW ROAD 17 Kamalapokhari Branch ACTIVE SOFTWARE PVT.LTD. MAHARAJGUNJ 18 Kamalapokhari Branch ADHIRAJ RAI CHISAPANI, KHOTANG 19 Kamalapokhari Branch ADITYA KUMAR KHANAL/RAMESH PANDEY CHABAHIL 20 Kamalapokhari Branch AFJAL GARMENT NAYABAZAR 21 Kamalapokhari Branch AGNI YATAYAT PVT.LTD KALANKI 22 Kamalapokhari Branch AIR NEPAL INTERNATIONAL P. LTD. HATTISAR, KAMALPOKHARI 23 Kamalapokhari Branch AIR SHANGRI-LA LTD. Thamel 24 Kamalapokhari Branch AITA SARKI TERSE, GHYALCHOKA 25 Kamalapokhari Branch AJAY KUMAR GUPTA HOSPITAL ROAD 26 Kamalapokhari Branch AJAYA MAHARJAN/SHIVA RAM MAHARJAN JHOLE TOLE 27 Kamalapokhari Branch AKAL BAHADUR THING HANDIKHOLA 28 Kamalapokhari Branch AKASH YOGI/BIKASH NATH YOGI SARASWATI MARG 29 Kamalapokhari Branch ALISHA SHRESTHA GOPIKRISHNA NAGAR, CHABAHIL 30 Kamalapokhari Branch ALL NEPAL NATIONAL FREE STUDENT'S UNION CENTRAL OFFICE 31 Kamalapokhari Branch ALLIED BUSINESS CENTRE RUDRESHWAR MARGA 32 Kamalapokhari Branch ALLIED INVESTMENT COMPANY PVT. -

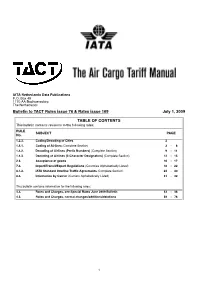

Bulletin to TACT Rules Issue 76 & Rates Issue 169 July 1, 2009

IATA Netherlands Data Publications P.O. Box 49 1170 AA Badhoevedorp The Netherlands Bulletin to TACT Rules issue 76 & Rates issue 169 July 1, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS This bulletin contains revisions to the following rules: RULE SUBJECT PAGE No. 1.2.3. Coding/Decoding of Cities 2 1.4.1. Coding of Airlines (Complete Section) 3- 8 1.4.2. Decoding of Airlines (Prefix Numbers) (Complete Section) 9- 11 1.4.3. Decoding of Airlines (2-Character Designators) (Complete Section) 12 - 15 2.3. Acceptance of goods 16 - 17 7.3. Import/Transit/Export Regulations (Countries Alphabetically Listed) 18 - 22 8.1.2. IATA Standard Interline Traffic Agreements (Complete Section) 23 - 30 8.3. Information by Carrier (Carriers Alphabetically Listed) 31 - 32 This bulletin contains information for the following rates: 4.3. Rates and Charges, see Special Rates June 2009 Bulletin 33 - 38 4.3. Rates and Charges, normal changes/additions/deletions 39 - 76 1 1.2.3. CODING/DECODING OF CITIES A. CODING OF CITIES In addition to the cities in alphabetical order the list below also contains: - Column 1: two-letter codes for states/provinces (See Rule 1.3.2.) - Column 2: two-letter country codes (See Rule 1.3.1.) - Column 3: three-letter city codes Additions: Cities 1 2 3 DEL CARMEN PH IAO NAJAF IQ NJF PSKOV RU PKV TEKIRDAG TR TEQ Changes: Cities 1 2 3 KANDAVU FJ KDV SANLIURFA TR SFQ B. DECODING OF CITIES In addition to the three-letter city codes (Column 1) in alphabetical order the list below also contains: - Column Cities: full name - Column 2: two-letter codes for states/provinces (See Rule 1.3.2.) - Column 3: two-letter country codes (See Rule 1.3.1.) Additions: 1 Cities 2 3 IAO DEL CARMEN PH NJF NAJAF IQ PKV PSKOV RU TEQ TEKIRDAG TR Changes: 1 Cities 2 3 KDV KANDAVU FJ SFQ SANLIURFA TR Bulletin, TACT Rules & Rates - July 2009 2 1.4.1. -

Overview of Tourism Development Prospects in Nepal

Overview of Tourism Development prospects in Nepal Dhakal, RangaNath 2015 Kerava Laurea University of Applied Sciences Kerava 1 Overview of Tourism Development prospects in Nepal RangaNath Dhakal Degree Programme in Tourism Bachelor’s Thesis January, 2015 2 Laurea University of Applied Sciences Abstract Kerava Tourism RangaNath Dhakal Prospect of Tourism Development in Nepal Year 2015 Pages 40 The aim of the thesis is to reflect the current profile of tourism in Nepal and to carry-out deep learning about the prospects of tourism development in Nepal along with interrelated national strategies and plans. This thesis investigates on the major role played by tourism for the development of a nation and initiations that are taken by government and local bodies to be in line with tourism development. For this thesis, analyzing the infrastructural support for the tourism development in Nepalese context was carried out. Basically secondary data relat- ing to the tourism industry of Nepal was collected through the web sites of various sources such as Nepal Tourism Board, National Planning Commission Nepal, and Bureau of Statistics Nepal and also through various journals published online to conclude the development horizon of tourism of Nepal. This thesis has briefly highlighted the existing development status of tourism in selected peripherals. And after the analysis of a national aggregate plan, the pro- spect of tourism development was highlighted by the work. In order to get the meaningful results Ex-post facto and analytical research method was adopted. Being the native, the natural beauty of Nepal has always remained in my attraction. Similarly, being under the graduation process in Laurea University of Applied Sciences under Degree Program in Tourism and compulsion to conduct thesis work in related field also motivated me for the tourism related study of Nepal. -

Tourism Policy, Possibilities and Destination Service Quality Management in Nepal

Tourism Policy, Possibilities and Destination Service Quality Management in Nepal by Bista Raghu Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Macedonia - Economics and Social Sciences Department of Applied Informatics, Thessaloniki, Greece Thesis Supervisor: Professor Zoe Georganta Doctoral Thesis Bista Raghu Tourism Policy, Possibilities and Destination Service Quality Management in Nepal by Bista Raghu Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Macedonia – Economic and Social Sciences Department of Applied Informatics, Thessaloniki, Greece Thesis Committee: Professor Zoe Georganta Professor Anastasios Katos Professor Vaios Lazos May 2009 Doctoral Thesis Bista Raghu 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to express my gratitude to all members of my supervising committee, Professors Zoe Georganta, Anastasios Katos and Vaios Lazos, for their valuable advice and academic supervision since my arrival to Greece. Their intellectual guidance has always motivated me to complete this Thesis. I am grateful to Dr. Christos Vasiliadis (Assistant Professor at the Department of Business Administration) for his continuous constructive support and scholar encouragement during all my stay in Greece. I am also thankful to the academic and administrative staff of the Department of Applied Informatics as well as the Department of Business Administration of the University of Macedonia, Economic and Social Sciences, who have greatly supported me in scientific and administrative matters, respectively. I am obliged to the Greek State Scholarships Foundation (IKY) for providing me with a four-year scholarship without which I would not be able to complete my research. I wish to express my thanks to friends from Greece and Nepal for their help and cooperation in various matters relating to the completion of this Thesis. -

Use CTL/F to Search for INACTIVE Airlines on This Page - Airlinehistory.Co.Uk

The World's Airlines Use CTL/F to search for INACTIVE airlines on this page - airlinehistory.co.uk site search by freefind search Airline 1Time (1 Time) Dates Country A&A Holding 2004 - 2012 South_Africa A.T. & T (Aircraft Transport & Travel) 1981* - 1983 USA A.V. Roe 1919* - 1920 UK A/S Aero 1919 - 1920 UK A2B 1920 - 1920* Norway AAA Air Enterprises 2005 - 2006 UK AAC (African Air Carriers) 1979* - 1987 USA AAC (African Air Charter) 1983*- 1984 South_Africa AAI (Alaska Aeronautical Industries) 1976 - 1988 Zaire AAR Airlines 1954 - 1987 USA Aaron Airlines 1998* - 2005* Ukraine AAS (Atlantic Aviation Services) **** - **** Australia AB Airlines 2005* - 2006 Liberia ABA Air 1996 - 1999 UK AbaBeel Aviation 1996 - 2004 Czech_Republic Abaroa Airlines (Aerolineas Abaroa) 2004 - 2008 Sudan Abavia 1960^ - 1972 Bolivia Abbe Air Cargo 1996* - 2004 Georgia ABC Air Hungary 2001 - 2003 USA A-B-C Airlines 2005 - 2012 Hungary Aberdeen Airways 1965* - 1966 USA Aberdeen London Express 1989 - 1992 UK Aboriginal Air Services 1994 - 1995* UK Absaroka Airways 2000* - 2006 Australia ACA (Ancargo Air) 1994^ - 2012* USA AccessAir 2000 - 2000 Angola ACE (Aryan Cargo Express) 1999 - 2001 USA Ace Air Cargo Express 2010 - 2010 India Ace Air Cargo Express 1976 - 1982 USA ACE Freighters (Aviation Charter Enterprises) 1982 - 1989 USA ACE Scotland 1964 - 1966 UK ACE Transvalair (Air Charter Express & Air Executive) 1966 - 1966 UK ACEF Cargo 1984 - 1994 France ACES (Aerolineas Centrales de Colombia) 1998 - 2004* Portugal ACG (Air Cargo Germany) 1972 - 2003 Colombia ACI -

Nepali Times

#258 29 July - 4 August 2005 16+4 pages Rs 30 LIFE IN A BUBBLE: Weekly Internet Poll # 258 Children going to school in Q... Should the parties respond to the Libang earlier this month in Maoist offer of negotiations? the middle of strife-torn Rolpa. Total votes:3881 Weekly Internet Poll # 259. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com How do you rate the new council of ministers with previous ones? KUMAR SHRESTHA KISHORE NEPAL in DIKTEL t has been six months since King Gyanendra took I over in Kathmandu promising to restore peace Meanwhile… but in remote district towns The rest of Nepal sees no hope in Kathmandu’s continued political paralysis across Nepal people are losing even the flicker of army has restricted teacher in Khotang. thought the army would go hope they had that the community forestry on When they find out we are after the Maoists but they are violence would soon end. suspicion that money from journalists from Kathmandu, coming after us,” is a Since February, I have timber sales was going to the peasants, teachers, traders, tea common refrain. traveled across Nepal: from rebels. shop owners, women and In Libang’s little bubble, Pyuthan, Rolpa, Achham in Teachers are being forced social workers across Nepal uniformed school children in the west to Terathum and to tear out and burn pages in always have the same ties go Charikot in the east. In new Grade Eight textbooks question: where is the peace to the Editorial p2 Terathum, Kamala Tamang’s that carry portraits and the that the king promised? only The freedom to be fair policeman husband was life histories of the royal They were already living private recently killed by Maoists family. -

Scheduled Airlines at Bangkok International Airport for Year 2005

8 “√®“°ª√–∏“π°√√¡°“√ Message from Chairman of the Board 12 §≥–°√√¡°“√ ∑Õ∑. AOT Board of Directors 16 §≥–ºŸâ∫√‘À“√ ∑Õ∑. AOT Senior Executives 24 º—ß°“√®—¥ à«πß“π Organization Chart 28 ¢âÕ¡Ÿ≈∑“ß°“√‡ß‘π‚¥¬ √ÿª¢Õß∫√‘…—∑ AOT Financial Summary 37 ≈—°…≥–°“√ª√–°Õ∫∏ÿ√°‘® Business Characters 40 º≈°“√¥”‡π‘πß“π¥â“π°“√„Àâ∫√‘°“√ An Overview of 2005 Operations 46 √–∫∫ª√–‡¡‘πº≈°“√¥”‡π‘πß“π Performance Evaluation System 50 ªí®®—¬§«“¡‡ ’Ë¬ß Risk Factors 58 ‚§√ß √â“ß°“√∂◊ÕÀÿâπ·≈–°“√®—¥°“√ “√∫—≠ Shareholding and Management Structure 74 √“¬°“√√–À«à“ß°—π Contents Related Party Transactions 81 ∂‘µ‘°“√¢π àß∑“ßÕ“°“» Air Traffic Statistics 90 ‚§√ß°“√æ—≤π“∑à“Õ“°“»¬“π°√ÿ߇∑æ„πÕ𓧵 The Future Development of Bangkok International Airport 92 °“√‡µ√’¬¡°“√∫√‘À“√∑à“Õ“°“»¬“π ÿ«√√≥¿Ÿ¡‘ Operational Readiness for Suvarnabhumi Airport 96 °“√∑¥ Õ∫∑“߇∑§π‘§√–∫∫ π“¡∫‘π ÿ«√√≥¿Ÿ¡‘ First Technical Flight 98 °‘®°√√¡‡™‘ßæ“≥‘™¬å Commercial Activities 103 °“√æ—≤π“∑√—欓°√∫ÿ§§≈ Human Resources Development 110 °“√¥”‡π‘πß“π¥â“π°“√®—¥°“√ ‘Ëß·«¥≈âÕ¡ Environmental Management and Conservation 114 √–∫∫°“√®—¥°“√§«“¡ª≈Õ¥¿—¬ Safety Management System 122 ¡“µ√°“√√—°…“§«“¡ª≈Õ¥¿—¬∑à“Õ“°“»¬“π Airport Security Measures 129 ß∫°“√‡ß‘π·≈–°“√«‘‡§√“–Àå°“√‡ß‘π Financial Statements and Analysis 8 9 “√®“°ª√–∏“π°√√¡°“√ Message from Chairman of the Board “√®“°ª√–∏“π°√√¡°“√ Message from Chairman of the Board «π∑— ’Ë 29 °π¬“¬π— 2548 π∫‡ª— π«ì π∑— ”§’Ë ≠Õ¬— “߬à ߢÕß‘Ë Airports of Thailand Public Company Limited (AOT) ∫√…‘ ∑∑— “Õ“°“»¬“π‰∑¬à ®”°¥— (¡À“™π) (∑Õ∑.) ∑∑’Ë “Õ“°“»¬“πà launched 2 flight operations on the 29th of September 2005 ÿ«√√≥¿Ÿ¡‘´÷Ë߇ªì𧫓¡¿Ÿ¡‘„®¢Õߧπ‰∑¬∑—Èß™“µ‘ “¡“√∂„Àâ as a profoundly important milestone in our history.