Mass Fainting in Garment Factories in Cambodia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kaplan & Sadock's Study Guide and Self Examination Review In

Kaplan & Sadock’s Study Guide and Self Examination Review in Psychiatry 8th Edition ← ↑ → © 2007 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com 978-0-7817-8043-8 © 2007 by LIPPINCOTT WILLIAMS & WILKINS, a WOLTERS KLUWER BUSINESS 530 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 USA, LWW.com “Kaplan Sadock Psychiatry” with the pyramid logo is a trademark of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including photocopying, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner, except for brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Materials appearing in this book prepared by individuals as part of their official duties as U.S. government employees are not covered by the above-mentioned copyright. Printed in the USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sadock, Benjamin J., 1933– Kaplan & Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry / Benjamin James Sadock, Virginia Alcott Sadock. —8th ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7817-8043-8 (alk. paper) 1. Psychiatry—Examinations—Study guides. 2. Psychiatry—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Sadock, Virginia A. II. Title. III. Title: Kaplan and Sadock’s study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. IV. Title: Study guide and self-examination review in psychiatry. RC454.K36 2007 616.890076—dc22 2007010764 Care has been taken to confirm the accuracy of the information presented and to describe generally accepted practices. However, the authors, editors, and publisher are not responsible for errors or omissions or for any consequences from application of the information in this book and make no warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the currency, completeness, or accuracy of the contents of the publication. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic Criteria for Research

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Diagnostic criteria for research World Health Organization Geneva The World Health Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations with primary responsibility for international health matters and public health. Through this organization, which was created in 1948, the health professions of some 180 countries exchange their knowledge and experience with the aim of making possible the attainment by all citizens of the world by the year 2000 of a level of health that will permit them to lead a socially and economically productive life. By means of direct technical cooperation with its Member States, and by stimulating such cooperation among them, WHO promotes the development of comprehensive health services, the prevention and control of diseases, the improvement of environmental conditions, the development of human resources for health, the coordination and development of biomedical and health services research, and the planning and implementation of health programmes. These broad fields of endeavour encompass a wide variety of activities, such as developing systems of primary health care that reach the whole population of Member countries; promoting the health of mothers and children; combating malnutrition; controlling malaria and other communicable diseases including tuberculosis and leprosy; coordinating the global strategy for the prevention and control of AIDS; having achieved the eradication of smallpox, promoting mass immunization against a number of other -

Appendix Charles C

APPENDIX CHARLES C. HUGHES GLOSSARY OF 'CULTURE-BOUND' OR FOLK PSYCHIATRIC SYNDROMES INTRODUCTION As suggested by Hughes in his Introduction to this volume, the term "culure bound syndromes" has an elusive meaning; in fact, the several conceptual elements that might imply a focused and exclusive reference for the phrase vanish upon examination, leaving a phrase that still has currency but little discriminable content. What remains appears to be more a feeling tone about certain patterns of behavior so unusual and bizarre from a Western point of view that, regardless of defmitional ambiguities, they have continued to be accorded by some writers a reified status as a different "class" sui generis of psychiatric or putatively psychiatric phenomena. Even if such a unique class were defensible, the topic is beset with sheer nota tional confusion. A reader may wonder, for example, whether terms resembling each other in spelling (e.g., bah tschi, bah-tsi) are reporting different disorders or simply reflecting differences in the authors' phonetic and orthographic tran scription styles for the same disorder. Or perhaps the various renderings are ac curately transcribed but represent dialectical differences in names used for a given syndrome by various groups having the same basic cultural orientation (e.g., win diga, witika, wihtigo, whitigo, wiitika)? In addition, of course, there may be entirely different terms for what is claimed to be essentially the same condition in diverse cultural groups (e.g., karo and shook yang). Dr. Simons noted in the foreword to this book that, as colleagues at Michigan State University over ten years ago, we began to think about such a volume. -

Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry

Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Clinical Manual of Cultural Psychiatry Second Edition Edited by Russell F. Lim, M.D., M.Ed. Washington, DC London, England Note: The authors have worked to ensure that all information in this book is accurate at the time of publication and consistent with general psychiatric and medical standards, and that information concerning drug dosages, schedules, and routes of administration is accurate at the time of publication and consistent with standards set by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the general medical community. As medical research and practice continue to advance, however, therapeutic standards may change. Moreover, specific situations may require a specific therapeutic response not included in this book. For these reasons and because human and mechanical errors sometimes occur, we recommend that readers follow the advice of physicians directly involved in their care or the care of a member of their family. Books published by American Psychiatric Publishing (APP) represent the findings, conclusions, and views of the individual authors and do not necessarily represent the policies and opinions of APP or the American Psychiatric Association. If you would like to buy between 25 and 99 copies of this or any other American Psychiatric Publishing title, you are eligible for a 20% discount; please contact Customer Service at [email protected] or 800-368-5777. If you wish to buy 100 or more copies of the same title, please e-mail us at [email protected] for a price quote. Copyright © 2015 American Psychiatric Association ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Manufactured in the United States of America on acid-free paper 181716151454321 Proudly sourced and uploaded by [StormRG] Second Edition Kickass Torrents | TPB | ET | h33t Typeset in Adobe Garamond and Helvetica. -

THE LEXICONS of PSYCHIATRY by the WORLD Heallh ORGANIZATION

THE LEXICONS Of PSYCHIATRY BY THE WORLD HEALlH ORGANIZATION Lexicon of Psgchiatric and Mental Health Terms Second Edition World Healt.h Organization Geneva 1994 Lexicon of Alcohol and Drug Terms World Health Organization Geneva 1997 Lexicon of Cross-Cultural Terms in Mental Health World Health Organization Gen('va 1994 S',~8)"~~ k II ~ I' II' ~ World Health Organization ""- ДЕКСИКОЛЫ ПСИХИАТРИИ ВСЕМИРНОЙ ОРГАНИЗАЦИИ ЗДРАВООХРАНЕНИЯ Лексикон осахоатрических о относящихся к психическому зуоровью терминов Второе оздание Лексикон терминов, относящихся к штт и уругом психоактивным среустоам Лексикон кросс-культуральных термопоо. относящихся к психическому зуеровью Перевод с английского под общей редакцией доц. В. Б. Позняка УДК 616.89(082) ББК 56.1я43 Л43 РиЬйЬеа Ьу йе \Уог1с1 НеаИЬ Оеагатайоп ипс1ег Ше ИИев Ьехкоп о/ рзускЫНс апй тепий кеаШ гегтз, 2Ы еД, Ьехкоп о/ акоЬЫ апй втщ 1еттл, Ьеххоп о/ сго85-си2(игаг ^е^т т тгпЫ ЬеаНН © Шт\й Неа№ Огеагагайоп, 1994,1997 ТЬе В1гес1ог-Сепега1 о{ Ше ШогЫ Неа11Ь Огеатгайоп Ьаз егаШей 1гапЕ1ааоп п$Ы& 1ог а опе-Уо1ите еШйоп т Низяап 1о ЗрЬеге РиЬизЫп§ Ноше, Иеу, тоЫсЬ 15 5о1е1у гезрогкМе 1ог Ше Низап еШйоа Перевод на русский язык и издание Лексиконов псгаиат- рии осуществлены благодаря гранту, предоставленному Генеральным директором Всемирной Организации Здраво охранения издательству «Сфера» (Киев), которое несет ответ ственность за издание книги на русском языке. 18ВК 966-7841-25-1 © Издательство «Сфера», ху дожественное оформле ние, 2001 Содержание Предисловие \т Лексикон психиатрических и относящихся -

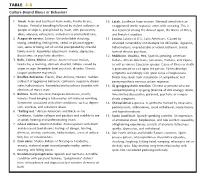

Table 5-8 for Examples (2, 14, 37, 112)

M05_MURR8663_08_SE_CH05.QXD 5/27/08 10:19 AM Page 131 Chapter 5 Sociocultural Influences 131 Influences of Culture on Health dark and light, hot and cold, hard and soft, or male and fe- male. An excess or shortage of elements in either direction causes discomfort and illness. CONCEPTS OF ILLNESS Many cultures explain the cause of and treatment for illness in one or Because every culture is complex, it can be difficult to deter- several of the following categories (2, 14, 37, 112): mine whether health and illness are the result of cultural or other elements, such as physiologic or psychological factors. Yet there are 1. Natural: Weather changes, bad food, or contaminated water numerous accounts of the presence or absence of certain diseases cause illness. in certain cultural groups and reactions to illness that are cultur- 2. Supernatural: The gods, demons, or spirits cause illness as pun- ally determined. ishment for faulty behavior, violation of the religious or ethi- Culture-bound illness or syndrome refers to disorders re- cal code, or an act of omission to a deity; or as a result of black stricted to a particular culture because of certain psychosocial charac- magic, voodoo, or evil incantation of an enemy or sorcerer. teristics of the people in the group or because of cultural reactions to the 3. Metaphysical: Health is maintained when nature and the body malfunctioning biological or psychological processes (2, 37, 112). See operate within a delicate balance between two opposites, such Table 5-8 for examples (2, 14, 37, 112). Culture and climate in- as Am and Duong (Vietnamese), yin and yang (Chinese), fluence food availability, dietary taboos, and methods of hygiene, which in turn affect health, as do cultural folkways. -

“Cultura Política Nicaragüense” Por El Dr. Emilio Álvarez Montalván

0 No. 78 – Octubre 2014 ISSN 2164-4268 revista dedicada a documentar asuntos referentes a Nicaragua CONTENIDO INFORMACIÓN EDITORIAL ............................................................................................... 4 NUESTRA PORTADA ............................................................................................................. 5 La Camerata Bach .......................................................................................................................................... 5 DE NUESTROS LECTORES .................................................................................................. 8 DEL ESCRITORIO DEL EDITOR ...................................................................................... 11 Guía para el Lector ....................................................................................................................................... 11 Reorganización de Revista de Temas Nicaragüenses ........................................................................................ 16 ENSAYOS ............................................................................................................................... 19 Antidio Cabal y el Historicismo marxista de una época .................................................................................. 20 Manuel Fernández Vílchez El español americano de El Güegüence o Macho-Ratón .................................................................................. 26 Enrique Balmaseda Maestu La Beata Nicaragüense Sor María Romero .................................................................................................. -

Johan Wedel: Bridging the Gap Between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua

Johan Wedel: Bridging the Gap between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua Bridging the Gap between Western and Indigenous Medicine in Eastern Nicaragua Johan Wedel University of Gothenburg, [email protected] ABSTRACT In Nicaragua there are attempts, at various levels, to bridge the gap between Western and indigenous medicine and to create more equal forms of therapeutic cooperation. This article, based on anthropological fieldwork, focuses on this process in the North Atlantic Autonomous Region, a province dominated by the Miskitu people. It examines illness beliefs among the Miskitu, and how therapeutic cooperation is understood and acted upon by medical personnel, health authorities and Miskitu healers. The study focuses on ailments locally considered to be caused by spirits and sorcery and problems that fall outside the scope of biomedical knowledge. Of special interest is the mass-possession phenomena grisi siknis where Miskitu healing methods have been the preferred alternative, even from the perspective of the biomedical health authorities. The paper shows that Miskitu healing knowledge is only used to compensate for biomedicine’s failure and not as a real alternative, despite the intentions in the new Nicaraguan National Health Plan. This article calls for more equal forms of therapeutic cooperation through ontological engagement by ongoing negotiation and mediation between local and biomedical ways of perceiving the world. KEYWORDS: Miskitu, medical pluralism, healing, grisi siknis, Nicaragua Introduction Today, in most complex societies, various healing systems exist parallel with biomedicine (Western medicine).1 Although these systems may collaborate, biomedicine usually ANTHROPOLOGICAL NOTEBOOKS 15 (1): 49–64. ISSN 1408-032X © Slovene Anthropological Society 2009 1 Anthropological fieldwork was carried out in the Eastern Nicaraguan city of Puerto Cabezas, in the regional capital of the RAAN, for a total period of eleven months during 2005–2008, and mainly funded by the Swedish Research Council (427–2005–8695). -

Cross Cultural Mental Health

No. 9, Winter 2000 BC’s Mental Health Journal Cross Cultural Mental Health poster (original in full-colour) c/o CMHA, Novia Scotia Division’s Cross Cultural (original in full-colour) c/o CMHA,poster Mental Health Initiative Novia Scotia Attitudes Approaches Accessibility Acceptance editor’s message he story underlying Dr. Terry ground? If not, where are the due to migration from countries TTafoya’s editorial [opposite gaps? And what can we learn from outside of Canada, 76% of whom page] is a powerful illustration of the people who deal with mental were people from an Asian the simple truth laid out in its fi- illness — i.e., consumers and fam- country. nal sentence: “There are different ily members — who come from dif- BC’s methods of healing because ferent backgrounds? What can we This edition reflects changes in Mental there are different needs of peo- learn from the traditions of knowl- the CMHA Editorial Staff. Eric Health ple.” And while the lesson applies edge and wisdom that people Macnaughton takes over the du- Journal to what the biomedical model bring with them? ties as Editor from Dena Ellery, might think of as “treatment,” it who has returned to school full- obviously relates to the other is- Considering this issue of cross cul- time. Sarah Hamid continues in Visions sues of cross cultural mental tural mental health is crucial, a Design and Production Editor health that this edition of Visions because there is still a long way capacity. Vinay Mushiana, the Co- is a quarterly publication pro- will address: access to services, to go, and much to learn in rela- ordinator of the Cross Cultural duced by the Canadian Mental appropriate methods of ass- tion to all of these questions. -

Migration and Psychopathology

Anuario de Psicología Clínica y de la Salud / Annuary of Clinical and Health Psychology, 4 (2008) 15-25 Migration and psychopathology Patricia Delgado Ríos1 INTECO. Research and Cognitive Therapy. Sevilla (España) ABSTRACT Given the social and political relevancy that in the last times is receiving the phenomenon, appears in this article a theoretical review of the relation among psycopathology and immigration. Analyzing the variables that influence the above mentioned relation (Genre, language and acculturation, conditions and stages of the migration, cultural differences as for the manifestation of psychiatric symptomatology, etc.) as well as the relative weight of each one of them in different aspects of the psycopathology. In this regard, one presents the integration Theory of Bhugra (2004), which analyzes the interaction among the stages of the migration and a series of factors of risk and protective. Now we´re going to detail the plot lines and the most significant results that the research has offered on psychopathologycal concrete disorders. Of among them, probably the most interesting ones have been the disorders for stress, especially from our country with the formulation of Ulises's Syndrome for Joseba Achotegui, and the psychotic disorders. Of the above mentioned, one presents the evolution in the hypotheses brings over of the relation among schizophrenia and the migration, in spite of which attempts it continues without being sufficiently clarified. It turns out indispensable to place all this boarding in a cultural frame, emphasizing in the modulation that the cultural environment exercises on the psychopathologycal manifestations, and naming some of the syndromes dependent on the culture as they are contemplated by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the Mental Disorders (DSM). -

Possession, Exorcisism, and Psychotherapy 52

POSSESSION, EXORCISISM, AND PSYCHOTHERAPY 52 Professional Issues in Counseling 2008, Volume 8, Article 6, p. 52-65 Possession, Exorcism and Psychotherapy Possession, Exorcism and Psychotherapy Timothy C. Thomason Northern Arizona University For all of recorded history, almost all human beings have believed in a spiritual plane of existence that somehow interacts with people in their daily life. A common belief is that souls, spirits, and demons exist, and that evil spirits can invade people and cause illness, especially mental illness. Throughout history the preferred method for eliminating evil spirits has been some form of ritual invocation or exorcism. Rather than dying out, belief in spirits, demons, and the supernatural is widespread today, in both highly industrialized societies like the U.S. and in less technologically developed countries. An understanding of how these beliefs came about and how they are practiced today can help psychologists provide appropriate services for clients with such beliefs. Keywords: possession, exorcism, psychotherapy Possession, Exorcism and Psychotherapy Introduction Could there ever be a situation in which a psychologist would be justified in conducting an exorcism for a client who was thought to be possessed by a demon? Although this scenario might sound unlikely, some psychologists have in fact conducted exorcisms in recent years. Given the widespread belief in the reality of supernatural phenomena such as demonic possession in America and throughout the world, psychologists need to have a basic understanding of why so many people believe in possession and participate in exorcism rituals. This article summarizes the history of belief in spirits and possession, the position of churches on the issue, and some psychological explanations for how exorcism could help "possessed" people. -

293096494.Pdf

h IC0 Clftn f Mntl nd hvrl rdr nt rtr fr rrh Wrld lth Ornztn Gnv 1993 eie 1997 3 WO iay Caaoguig i uicaio aa e IC-1 cassiicaio o mea a eaioua isoes iagosic cieia o eseac 1 Mea isoes — cassiicaio Mea isoes — iagosis IS 9 1555 (M Cassiicaio WM 15 © Wo ea Ogaiaio 1993 A igs esee uicaios o e Wo ea Ogaiaio ca e oaie om Makeig a issemiaio Wo ea Ogaiaio Aeue Aia 111 Geea 7 Swiea (e +1 791 7; a +1 791 57; emai ookoeswoi equess o emissio o eouce o asae WO uicaios—wee o sae o o ocommecia isiuio—sou e aesse o uicaios a e aoe aess (a +1 791 ; emai emissios woi e esigaios emoye a e eseaio o e maeia i is uicaio o o imy e eessio o ay oiio wasoee o e a o e Seceaia o e Wo ea Ogaiaio coceig e ega saus o ay couy eioy ciy o aea o o is auoiies o coceig e eimiaio o is oies o ouaies e meio o seciic comaies o o seciic mauacues oucs oes o imy a ey ae eose o ecommee y e Wo ea Ogaiaio i eeece o oes o a simia aue a ae o meioe Eos a omissios ecee e ames o oieay oucs ae isi- guise y iiia caia ees e Wo ea Ogaiaio oes o waa a e iomaio coaie i is uicaio is comee a coec a sa o e iae o ay amages icue as a esu o is use ie i Swiea eie i Maa 93/91 — 9/1111 — 1 /19 — Iei — 1 Cntnt eace Ackowegemes oes o uses 1 IC-1 Cae ( a associae iagosic isumes 4 is o caegoies 5 iagosic cieia o eseac 7 Ae 1 oisioa cieia o seece isoes 173 Ae Cuue-seciic isoes 17 is o iiiua ees 19 is o ie ia cooiaig cees ie ia cees eoig o em a iesigaos 191 Ie 3 iii rf I e eay 19s e Mea ea ogamme o e Wo ea Ogaia- io (WO ecame aciey egage i a ogamme aimig o imoe e iagosis a cassiicaio o mea isoes A a