The Behavioural Dynamics of Romania's Foreign Policy In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RADU Vaslle Amintirile Unui Prim-Ministru RADU VASILE. Născut La 10 Octombrie 1942, La Sibiu. Absolvent Al Facultătii De Istor

RADU VASlLE Amintirile unui prim-ministru RADU VASILE. Nãscut la 10 octombrie 1942, la Sibiu. Absolvent al Facultãtii de Istorie, Universitatea Bucuresti —1967; Doctor în stiinte economice —1977; Profesor universitar la ASE —1993; Prim-ministru al României: 1998-1999. Autor a numeroase lucrãri în domeniul istoriei economiei; autor al romanului Fabricius si al volumelor de poezii Pacientul român si Echilibru în toate. Doresc sã multumesc cîtorva persoane fãrã de care aceastã carte nu ar fi existat. Lui Sorin Lavric, redactorul acestor pagini, care m-a ajutat sãpun în formã finalã experienta acestor ultimi 12 ani din viata mea, cu tot alaiul degîn-duri si sentimente care i-a însotit. Gabrielei Stoica, fosta mea consilierã, care m-a ajutat sã refac traseul sinuos al evenimentelor pe care le-am trãit. Dedic aceastã carte mamei, sotiei si copiilor mei, a cãror dragoste a fost si este adevãrata mea putere. CUVÎNT ÎNAINTE M-am întrebat deseori de unde nevoia politicienilor de a-si pune pe hîrtie amintirile fãrã sã se întrebe mai întîi dacã gestul lor serveste cuiva sau la ceva. Pornirea de a scrie despre orice si oricine, si de a te plasa în centrul unor evenimente doar pentru cã ai avut ocazia, în cursul lor, sã faci politicã la vîrf ascunde o tendintã exhibitionistã a cãrei justificare e de cãutat în cutele insesizabile ale vanitãtii umane. Trufia celor care, scriind, îsi închipuie cã de mãrturisirile lor poate atîr-na mãcar o parte infimã din soarta politicii românesti de dupã ei tine de o iluzie strãveche, adînc înrãdãcinatã, aceea cã descriind rãul petrecut, îi poti micsora consecintele chiar si dupã ce el s-a întîmplat; sau cã mãcar îl poti preveni pe cel care urmeazã sã se întîm-ple. -

Media Influence Matrix Romania

N O V E M B E R 2 0 1 9 MEDIA INFLUENCE MATRIX: ROMANIA Author: Dumitrita Holdis Editor: Marius Dragomir Published by CEU Center for Media, Data and Society (CMDS), Budapest, 2019 About CMDS About the authors The Center for Media, Data and Society Dumitrita Holdis works as a researcher for the (CMDS) is a research center for the study of Center for Media, Data and Society at CEU. media, communication, and information Previously she has been co-managing the “Sound policy and its impact on society and Relations” project, while teaching courses and practice. Founded in 2004 as the Center for conducting research on academic podcasting. Media and Communication Studies, CMDS She has done research also on media is part of Central European University’s representation, migration, and labour School of Public Policy and serves as a focal integration. She holds a BA in Sociology from point for an international network of the Babes-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca and a acclaimed scholars, research institutions and activists. MA degree in Sociology and Social Anthropology from the Central European University. She also has professional background in project management and administration. She CMDS ADVISORY BOARD has worked and lived in Romania, Hungary, France and Turkey. Clara-Luz Álvarez Floriana Fossato Ellen Hume Monroe Price Marius Dragomir is the Director of the Center Anya Schiffrin for Media, Data and Society. He previously Stefaan G. Verhulst worked for the Open Society Foundations (OSF) for over a decade. Since 2007, he has managed the research and policy portfolio of the Program on Independent Journalism (PIJ), formerly the Network Media Program (NMP), in London. -

Post-Communist Romania: a Peculiar Case of Divided

www.ssoar.info Post-communist Romania: a peculiar case of divided government Manolache, Cristina Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Manolache, C. (2013). Post-communist Romania: a peculiar case of divided government. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 13(3), 427-440. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-448327 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Post-Communist Romania 427 Post-Communist Romania A Peculiar Case of Divided Government CRISTINA MANOLACHE If for the most part of its post-communist history, Romania experienced a form of unified government based on political coalitions and alliances which resulted in conflictual relations between the executive and the legislative and even among the dualist executive itself, it should come as no surprise that the periods of divided government are marked by strong confrontations which have culminated with two failed suspension attempts. The main form of divided government in Romania is that of cohabitation, and it has been experienced only twice, for a brief period of time: in 2007-2008 under Prime-Minister Călin Popescu Tăriceanu of the National Liberal Party and again, starting May 2012, under Prime Minister Victor Ponta of the Social Democratic Party. -

Viața La Sat În Perioada Comunistă

Flavius-Cristian MĂRCĂU Sorin PUREC VIAȚA LA SAT ÎN PERIOADA COMUNISTĂ COORDONATORI: Flavius-Cristian MĂRCĂU Sorin PUREC VIAȚA LA SAT ÎN PERIOADA COMUNISTĂ Editura Academica Brâncuși Editor: Flavius-Cristian MĂRCĂU Corectură: Iuliu-Marius MORARIU ISBN 978-973-144-783-4 EDITURA ACADEMICA BRÂNCUȘI ADRESA: Bd-ul Republicii, nr. 1 Târgu Jiu, Gorj Tel: 0253/218222 COPYRIGHT: Sunt autorizate orice reproduceri fără perceperea taxelor aferente cu condiţia precizării sursei. Responsabilitatea asupra conţinutului lucrării revine în totalitate autorilor. CUPRINS I 1 Sorin PUREC Prefață 7 2 Flavius-Cristian Moștenirile comuniste și memoria 13 MĂRCĂU nostalgică din statele Cetral- Europene 3 Iuliu-Marius Elemente ale opresiunii comuniste în 31 MORARIU localitatea Salva, județul Bistrița- Năsăud 4 Bianca OSMAN Manifestări ale mentalului colectiv. 45 rolul mass-media în formarea conștiinței individuale și de grup în perioada 1965-1990 II 5 Bianca OSMAN Interviu cu ADRIAN GORUN 65 6 Bianca OSMAN Interviu cu GEORGE NICULESCU 87 7 Claudia Interviu cu GHEORGHE GORUN 103 ȘOIOGEA 8 Claudia Interviu cu NICOLAE BRÎNZAN 121 ȘOIOGEA 9 Iuliu-Marius Interviu cu GRIGORE FURCEA 137 MORARIU 5 10 Iuliu-Marius Interviu cu DOREL MITITEAN 149 MORARIU 11 Bianca Interviu cu P. C. 161 LĂZĂROIU 12 Bianca OSMAN Interviu cu SIMA AUREL 167 13 Claudia Interviu cu CĂLUGĂRU ANGELA 173 ȘOIOGEA 14 Oana CALOTĂ Interviu cu NICU PÎRVULEȚ 179 15 Iuliu-Marius Interviu cu RADU BOTIȘ 189 MORARIU 16 Maria Interviu cu CIOCOIU OTILIA 195 VÎLCEANU 17 Costina Vergina Interviu cu CONSTANTIN 201 ȘTEFĂNESCU STEFĂNESCU 6 PREFAȚĂ „Cei care uita trecutul sunt condamnați sa îl repete”. George Santayana Ca să nu uităm dramele care ne-au marcat pe noi sau pe părinții și pe bunicii noștri, cartea de față adună, prin eforturile studenților noștri, o serie de interviuri realizate cu oameni care au petrecut ani ai regimului comunist la țară. -

CONTENTS PREFACE by PIERRE GUIRAL Ix FOREWORD Xi INTRODUCTION 1 ONE: DESTINY of the JEWS BEFORE 1866 1

CAROL IANCU – Romanian Jews CONTENTS PREFACE BY PIERRE GUIRAL ix FOREWORD xi INTRODUCTION 1 ONE: DESTINY OF THE JEWS BEFORE 1866 1. Geopolitical Development of Romania 13 2. Origin of the Jews and Their Situation Under the Native Princes 18 3. The Phanariot Regime and the Jews 21 4. The Organic Law and the Beginnings of Legal Anti-Semitism 24 5. 1848: Illusive Promises 27 6. The Jews During the Rebirth of the State (1856-1866) 30 TWO: THE JEWISH PROBLEM BECOMES OFFICIAL 1. Article 7 of the Constitution of 1866 37 2. Bratianu's Circulars and the Consequences Thereof 40 3. Adolphe Crémieux, The Alliance, and Émile Picot 44 4. Sir Moses Montefiore Visits Bucharest 46 THREE: PERSECUTIONS AND INTERVENTIONS (1868-1878) 1. The Disturbances of 1868 and the Draft Law of the Thirty-One and the Great Powers 49 2. The Circulars of Kogalniceanu and Their Consequences 55 3. Riots and Discriminatory Laws 57 4. Bejamin Peixotto's Mission 61 FOUR: FACTORS IN THE RISE OF ANTI-SEMITISM 1. The Religious Factor 68 2. The Economic Factor 70 3. The Political Factor 72 4. The Xenophobic Factor 74 FIVE: PORTRAIT OF THE JEWISH COMMUNITY 1. Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews: Clothing, Language, Names, Habitat, Occupations 77 2. Demographic Evolution 82 3. Disorganization of Community Life 84 4. Isolation and Integration 85 SIX: THE CONGRESS OF BERLIN AND NON-EMANCIPATION 1. Romania and the Jews in the Wings of the Berlin Congress 90 2. Article 44 of the Berlin Treaty 92 3. Emancipation or Naturalization? 94 4. The New Article 7 of the Constitution and Recognition of Romanian Independence 105 SEVEN: ANTI-SEMITIC LEGISLATION 1. -

Legislative Inflation – an Important Cause of the Dysfunctions Existing in Contemporary Public Administration

Legislative inflation – an important cause of the dysfunctions existing in contemporary public administration Professor Mihai BĂDESCU1 Abstract The study analyzes one of the major causes of the malfunctions currently in public administration: legislative inflation. Legislative inflation (or normative excess) should be seen as an unnatural multiplication of the norms of law, with negative consequences both for the elaboration of the normative legal act, the diminution – significant in some cases – of its quality, but also with regard to the realization of the law, especially in the enforcement of the rules of law by the competent public administration entities. The study proposes solutions to overcome these legislative dysfunctions, the most important of which refer to the rethinking of the current regulatory framework, the legislative simplification, the improvement of the quality of the law-making process, especially by complying with the legislative requirements (principles), increasing the role of the Legislative Council. The methods of scientific research used are adapted to the objectives of the study: the logical method - consisting of specific procedures and methodological and gnoseological operations, to identify the structure and dynamics of the legal system of contemporary society; the comparative method – which allows comparisons of the various legal systems presented in this study; the sociological method – which offers a new perspective on the study of the legal reality that influences society in the same way as it calls for the emergence of new legal norms; the statistical method – which allows statistical presentation of the most relevant data that configures the analyzed phenomenon. The study aims to raise awareness of the negative effects of regulatory excess. -

Crisis Management in Transitional Societies: the Romanian Experience

Crisis Management in Transitional Societies: The Romanian Experience Crisis Management in Transitional Societies: The Romanian Experience Editors: Julian Chifu and Britta Ramberg Crisis Management in Transitional Societies: The Romanian Experience Editors: Iulian Chifu and Britta Ramberg Crisis Management Europe Research Program, Volume 33 © Swedish National Defence College and CRISMART 2007 No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. Swedish material law is applied to this book. The contents of the book has been reviewed and authorized by CRISMART. Series editor: Bengt Sundelius Editors: Iulian Chifu and Britta Ramberg Printed by: Elanders Gotab 52862, Stockholm 2007 ISSN 978-91-85401-64-2 ISBN 1650-3856 For information regarding publications published by the Swedish National Defence College, call +46 8 553 42 500, or visit www.fhs.se/publikationer. See also www.crismart.org Table of Contens Foreword Britta Ramberg and Iulian Chifu 7 List of Acronyms 9 I. Introduction 11 Chapter 1 – Introduction Britta Ramberg and Iulian Chifu 13 Chapter 2 – The Political and Institutional Context of Crisis Management in Romania Ionut Apahideanu 41 II. Creeping Crises 71 Chapter 3 – Coping with a Creeping Crisis: The Government’s Management of Increased Drug Trafficking and Consumption in Romania Lelia-Elena Vasilescu 73 Chapter 4 – The Romanian Healthcare Crisis, 2003 Oana Popescu 115 III. Acute Domestic Crises 151 Chapter 5 – Bribery in the Government Ionut Apahideanu and Bianca Jinga 153 5 Table of Contents Chapter 6 – The Jean Monet Bombing Delia Amalia Pocan 191 Chapter 7 – The 1998–1999 Miners’ Crisis Cornelia Gavril 215 Chapter 8 – The National Fund for Investments Andreea Guidea 253 IV. -

Cât De Important Este Locul Exact În Care a Decedat Dr. Vasile Lucaciu?

S`n`tate & Frumuse]e Ceapa este un leac deosebit ~notul `mbun[t[\e;te Molarii de minte< Gen\ile must-have ale de eficient, mai ales în r[celi starea de spirit utili sau nu? sezonului de iarn[ 2018 PAGINA 6 PAGINA 8 PAGINA 9 PAGINA 7 Anul XVI Nr. 768 Duminic[ 21 ianuarie 2018 I Se distribuie `mpreun[ cu Informa\ia Zilei Batiste cu monograma lui Iuliu Maniu, lucrate manual de femeile Cât de important este locul exact din B[d[cin Comunitatea femeilor de la Bă - dăcin, satul în care în care a decedat dr. Vasile Lucaciu? se află casa memo - rială a lui Iuliu Ma - niu lucreaz[ la o Se `mplinesc inedită colecţie de batiste de buzunar. 166 de ani Materialele folosite sunt pânză de casă de la na;terea din bumbac, cânepă, pânză de in şi sunt brodate cu aţă de bumbac sau mătase, cu simboluri tradiţionale româneşti. Por - marelui nind de la batista lucrată de mama lui Iu - liu Maniu, colecţia va include şi o serie memorandist de "batiste suvenir", cu monograma lui Dac[ locul ;i data `n care v[d Iuliu Maniu ca un omagiu pentru marele om politic şi pentru Centenar. lumina zilei marile personalit[\i deseori se sacralizeaz[, nu mai pu\in important este momentul ;i locul `n care o mare personali - tate `nceteaz[ din via\[. Repere morale ale unei na\iuni, ele devin Ambasada Rom]niei la locuri de pelerinaj. ~n jude\ul Satu Budapesta a fost vandalizat[ Mare exist[ c]teva repere. Ma - ghiarii se adun[ la casa `n care s- Extremiştii maghiari au vandalizat a n[scut poetul Ady Endre sau faţada Ambasadei României la Budapesta Kolcsey Ferenc, autorul imnului prin acoperirea stemei naţionale cu stea - na\ional al Ungariei. -

Romania Assessment

Romania, Country Information Page 1 of 52 ROMANIA October 2002 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURE VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATION ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE REFRENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY http://194.203.40.90/ppage.asp?section=189&title=Romania%2C%20Country%20Informat...i 11/25/2002 Romania, Country Information Page 2 of 52 2.1 Romania (formerly the Socialist Republic of Romania) lies in south-eastern Europe; much of the country forms the Balkan peninsula. -

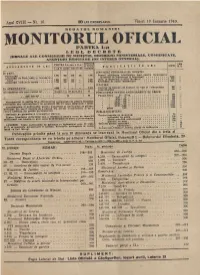

Monitorul Oficial Din a Treiazi Toatà Corespondenta Se Va Trimite Pe Adresa :Monitorul Oficial, Bucureti I.Bulevardul Elisabeta, 29 Telegramemon1toficial

Anul CVIII Nr. 16. lo LEI EXEMPLARCIL Vineri 19 Ianuarie 1940. REGATUL ROMANIEI MONITORULPARTEA I-a OFICIAL LEGI, DECRETE JURNALE ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRY,DECIZIUNI MINISTERIALE, COMUNICATE, ANUNTURI )IUDICIARE (DE INTERES GENERAL). PARTEA I-a sau a II-a Detbaterile LINIA ABONAMENTE IN LEI rlamont. PUBLIC ATII Itt LEI laterbe M. 0, I an 16 luni 3 luni 1 lunftpsesitine JURNALELE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI IN TARA: Pentru acordarea avantajelor legil pentru incurajarea 1900 1 950 475 160 1200 Particu lari 3.000 Autoritftti de Stat, judet si comune ur- industriel la industrlasi si fabricantl... ..... 1.200 Idem, la meseriasi si mori taranesti . 700 bane 1 600 800 400 L000 AutoritAti comunale rurale 1.100 '350 275 1.200 Schimbitri de nume 1neetAteniri . CITATIILE 2.400 Curtilor de Casatie, de Conturi, de Apel siI ribunalelor 300 4 0(Xl 150 IN STRAINATATE Judeciitorillor ... .. 1:1n exemplar din anul curent lei 10 part. I-a15 part. Il-a 10 PUBLICATIILE PENTRU AMENAJAMENTE DE PADURI 100 20 Padurl intre 0 10 ha anti trecull . 30 10,01 20 200 2E,01 100 .. 300 Abonamentul la partea Ill-a (Desbateri e parlamentare) pentru sesiunile 100,01 200 1.000 prelunglte sau extraordinare se socoteste 200 lei lunar (minimum 1luni). 200,01 500 1500 500.01-1000 2.000 Abonamentele si publicatille pentru autoritAti si particulari se plAtesc 3 000 anticipat. Ele vor fi insotite de o adresâ din parten utoritAtilor si de o : peste 1000 cerere timbrati din partea particularllor PUBLICATII DIVERSL Institutia nu garanteaza transportul ziarutui. Pentru brevete de inventium 70 Pentru trimiterea chitantelor sau a ziaruluii pentru cereri de lamuriri schimbAri de nume . -

![PCR Şi Guvernanţi – Nomenclatura Şi Colaboratorii [Sinteză Livia Dandara]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0500/pcr-%C5%9Fi-guvernan%C5%A3i-nomenclatura-%C5%9Fi-colaboratorii-sintez%C4%83-livia-dandara-2420500.webp)

PCR Şi Guvernanţi – Nomenclatura Şi Colaboratorii [Sinteză Livia Dandara]

AUTORII GENOCIDULUI: PCR şi guvernanţi – nomenclatura şi colaboratorii [sinteză Livia Dandara] [LD: Paradoxal, ei apar foarte rar în documentele care descriu represiunile , deoarece ordinele lor de arestare , date pe linie ierarhică de guvern şi partid, erau executate de Securitate şi Miliţie , iar procesele erau în competenţa procurorilor şi judecătorilor .De aceea am pus în fruntea acestor tabele adevăraţii autori politici şi morali ai genocidului .Istoricii -sau Justiţia ? sau Parlamentul ? -ar trebui să scoată la iveală Tabelele cu activiştii de partid -centrali şi locali - care , în fond, au alcătuit "sistema " regimului totalitar comunist. Pentru că : Gheorghiu -Dej, Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu , Petru Groza, Teohari Georgescu , Vasile Luca , Ana Pauker, Miron Constantinescu , ş.a ş.a, au depus tot zelul pentru a emite decrete-legi, instrucţiuni, circulare , ordine de zi, prin care s-a realizat crima decapitării elitelor româneşti Vezi Tabelul Cronologia represiunii] ------------------------------------------------ - Nicoleta Ionescu-Gură, Nomenclatura Comitetului Central al PMR. Editura Humanitas, Bucureşti, 2006. Anthologie cu 75 documente./ Reorganizarea aparatului CC al PMR (1950-1965) / Secţiile CC al PMR / Aparatul local / Evoluţia numerică şi compoziţia aparatului de partid / Salarizarea, orarul de lucru, regimul pensiilor, bugetul PMR / Nomenclatura CC al PMR :evoluţia numerică ; evidenţa cadrelor / Privilegiile nomenclaturii CC al PMR : Casele speciale,centrele de odihnă, policlinici şi spitale cu regim special, fermele partidului -

Managementul Timpului În Eficientizarea Activității Instituției De Învățământ

UNIVERSITATEA PEDAGOGICĂ DE STAT „ION CREANGĂ” Cu titlu de manuscris CZU: 37.01(043.3) MELNIC NATALIA MANAGEMENTUL TIMPULUI ÎN EFICIENTIZAREA ACTIVITĂȚII INSTITUȚIEI DE ÎNVĂȚĂMÂNT SPECIALITATEA 531.01 – TEORIA GENERALĂ A EDUCAȚIEI Teză de doctor în științe pedagogice Conducător științific: Cojocaru Vasile, doctor habilitat în pedagogie, profesor universitar Autorul: Melnic Natalia Chișinău, 2019 © MELNIC NATALIA, 2019 2 CUPRINS ADNOTARE (română, rusă, engleză) ………………………………………………… 5 INTRODUCERE ……………………………………………...……………………… 8 1. TIMPUL CA RESURSĂ A EDUCAȚIEI ŞI CONDIŢII DE EFICIENŢĂ ÎN PERSPECTIVA MANAGEMENTULUI INSTITUŢIEI DE ÎNVĂŢĂMÂNT …. 19 1.1. Conceptul și fațetele timpului din perspectiva filosofică, socială, pedagogică …... 19 1.2. Formele de existenţă şi caracteristicile timpului ...................................................... 24 1.3. Timpul ca resursă a educaţiei şi condiţii de eficienţă ............................................... 35 1.4. Managementul instituţiei de învăţământ în context temporal şi de schimbare ......... 41 1.5. Concluzii la capitolul 1 …………………………………………………………..... 52 2. MANAGEMENTUL TIMPULUI ÎN DEZVOLTAREA PERSONALĂ ȘI ORGANIZAȚIONALĂ ………………………………………………………………. 53 2.1. Managementul timpului în perspectiva eficienţei instituţiei de învăţământ ............. 53 2.2. Managementul timpului în implementarea curriculumului educaţional ................... 61 2.3. Proiectarea formării competenţelor în timp .............................................................. 76 2.4. Managementul timpului universitar