CONTENTS PREFACE by PIERRE GUIRAL Ix FOREWORD Xi INTRODUCTION 1 ONE: DESTINY of the JEWS BEFORE 1866 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONSTITUȚIE*) Din 21 Noiembrie 1991 (*Republicată*) EMITENT PARLAMENTUL Publicat În MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr

CONSTITUȚIE*) din 21 noiembrie 1991 (*republicată*) EMITENT PARLAMENTUL Publicat în MONITORUL OFICIAL nr. 767 din 31 octombrie 2003 Notă *) Modificată și completată prin Legea de revizuire a Constituției României nr. 429/2003, publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 758 din 29 octombrie 2003, republicată de Consiliul Legislativ, în temeiul art. 152 din Constituție, cu reactualizarea denumirilor și dându-se textelor o noua numerotare (art. 152 a devenit, în forma republicată, art. 156). Legea de revizuire a Constituției României nr. 429/2003 a fost aprobată prin referendumul național din 18-19 octombrie 2003 și a intrat în vigoare la data de 29 octombrie 2003, data publicării în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 758 din 29 octombrie 2003 a Hotărârii Curții Constituționale nr. 3 din 22 octombrie 2003 pentru confirmarea rezultatului referendumului național din 18-19 octombrie 2003 privind Legea de revizuire a Constituției României. Constituția României, în forma inițială, a fost adoptată în ședința Adunării Constituante din 21 noiembrie 1991, a fost publicată în Monitorul Oficial al României, Partea I, nr. 233 din 21 noiembrie 1991 și a intrat în vigoare în urma aprobării ei prin referendumul național din 8 decembrie 1991. Titlul I Principii generale Articolul 1 Statul român (1) România este stat național, suveran și independent, unitar și indivizibil. (2) Forma de guvernamant a statului român este republica. (3) România este stat de drept, democratic și social, în care demnitatea omului, drepturile și libertățile cetățenilor, libera dezvoltare a personalității umane, dreptatea și pluralismul politic reprezintă valori supreme, în spiritul traditiilor democratice ale poporului român și idealurilor Revoluției din decembrie 1989, și sunt garantate. -

The South Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Nationalitaetenrecht: The outhS Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy Sean Krummerich University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, and the European History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Krummerich, Sean, "Nationalitaetenrecht: The outhS Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4111 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalitätenrecht: The South Slav Policies of the Habsburg Monarchy by Sean Krummerich A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts & Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor, Graydon A. Tunstall, Ph.D. Kees Botterbloem, Ph.D. Giovanna Benadusi, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 6, 2012 Keywords – Austria, Hungary, Serb, Croat, Slovene Copyright © 2012, Sean Krummerich Dedication For all that they have done to inspire me to new heights, I dedicate this work to my wife Amanda, and my son, John Michael. Acknowledgments This study would not have been possible without the guidance and support of a number of people. My thanks go to Graydon Tunstall and Kees Boterbloem, for their assistance in locating sources, and for their helpful feedback which served to strengthen this paper immensely. -

Economics the ROLE of DIMITRIE CANTEMIR

“Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University Knowledge Horizons - Economics Volume 6, No. 2, pp. 209–211 P-ISSN: 2069-0932, E-ISSN: 2066-1061 © 2014 Pro Universitaria www.orizonturi.ucdc.ro THE ROLE OF DIMITRIE CANTEMIR IN THE ROMANIAN PEOPLE’S CULTURE Anda -Nicoleta ONE ȚIU Lecturer, Universitary Doctor, The Faculty of International Relations, „Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University , Bucharest, Economic, Romania, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Dimitrie Can temir, was twice Prince of Moldavia (in March -April 1693 and in 1710 -1711). He was Key words: also a prolific man of letters, philosopher, historian, composer, musicologist, linguist, etnographer Geographer, and geographer between 1711 and 1719, he wrote his most important creations. Cantemir was philosopher, historian, known as one of the greatest linguists of his time, speaking and writing eleven languages and being composer, linguist well versed in Oriental Scholarship. This oeuvre is voluminous, diverse and original; although some JEL Codes: of his scientic writings contain unconfirmed theories, his expertise, sagacity and groundbreaking. 1. Introduction Soultan’s Court, but, even if he was involved in such As a romanian chronicler (author of chronicles), Dimitrie conditions, he followed his path to learn at the Cantemir represents the most important personality of Patriarchy’s Academy, in order to complete his studies the romanian literature in the feudal era. He won the in such fields as: logics, philosophy, geography, history, respect of his contemporary intellectuals and of his medicine, chemistry and occidental languages. The descendants, he impressed by his own strong interest of the young moldavian in literature and personality as a symbol for the whole mankind, grace of occidental sciences was encouraged by the diplomats his studies concerning some fields as: history, of the occidental states and travelling through the geography, politics, music, mathematics and physics. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

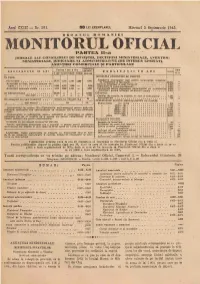

Monitorul Oficial Dill a Dotta Zi

Anul CXIII Nr. 201. 00 LEI EXEMPLARUL illiereurl 5 Septemvrie 1945. 11. REUATHL ROMANIEI MONITORULPARTEA ElaL OFICIAL JURNALE .ALE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI, DECIZIUNI MINISTERIALE, ANUNTUR1 MINISTERIALE, JUDICIARE SI ADMINISTRATIVE (DE INTERES LIMITAT), ANUNTURI COMERCIALE SI PARTICULARE 101form. flesbatarile Partea I sari a II-a LINIA ABONAMENTE IN LEI parlament. PUBLICATII IN LE/ laser* 0. ..... 1 anIsIunhI3IunhIlIunäl sesiune IN TARA: JURNALELE CONSILIULUI DE MINISTRI Particulari 10 0005.000 2.500 1.200 6.000 Acordarea avantajelor legii pentru incurajarea industriei la industriasii fabricanti 20.000 Autoritati de Stat, judet si comune ur- Idem la meseriasi si mori tam-most! 4.030 bane 8.000 4.000 2.000 MOO 6.000 Schimbäri de nume, incetäteniri 8 000 .Autorltitti comunale rurale 4.000 2.000 1.000 6.090 Conannicate pentru depunerea juritmfintului de incetatenire8.000 AutorizAri pentru inflintari de birouri vamale ....... 5.000 IN STRAINATATE I 25.000 . 1 12.000 CITATIILE: tine lunri am= mf On. 2.500 Curtilor de Casatle, de Conturi, de Apeii tribunalelor 1.500 Judedttoriilor 750 50 part. I-a60 part. ll-a so Un exemplar din anul curent loi PUBLICATIILE PENTRU AMENAJAMENTE DE PADURI: too ff es anti trecuti Ptiduri intro 0 10 ha 800 PM... 20 1 900 Abonarnentul la partea Ill-a (Desbaterile parlamentare) pentru sesitmile If « 20,01 100 2 500 Ordinare, prelttngite sau extraordinaro se socoteste 1.200 lei lunar (minimum 100,01 200 10 000 I lunä). 200,01 509 15.000 Abonamentele si 131:Mica-title, pentru autoritAtl siparticulari se platesc 7, 500,01-1000 25.000 anticipat. Ele vor fiInsotite de o adresti din partea autoritritilor si de o peste 1009 30 000 cerere timbratil din partea particularilor. -

El Paso Del Ebro Oooooooooooooooooooooooooo

EL PASO DEL EBRO OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO Trimestral sobre el red OOOOOOOOOO La primera guerra mundial, la segunda guerra mundial, l'actual guerra colonial, la próxima guerra del imperialismo americano-sionista y el revisionismo histórico OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO Numéro 20, otoño de 2006 y invierno de 2007 000000000000000000000 <elrevisionista at yahoo.com.ar> ooooooooooooooooooooooooo http://revurevi.net http://aaargh.com.mx ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo El argumento de los negadores del Holocausto proviene de un adagio muy conocido: "La historia la escriben los vencedores". Humberto Caspa (Diario La estrella. Texas) Los intelectuales sostienen que la "verdad del Estado" no es "la verdad histórica" SUMARIO El Holocausto, según Teherán, Ana Carbajosa Conferencia de Teherán : vease http://aaargh.com.mx/fran/livres7/teheran/teheran.html o http://revurevi.net La conferencia de Teherán y los Faurisson [1] proisraelíes, Bruno Guigue Faurisson enfrenta al aparato judicial francés a un nuevo desafío Otra historia del Holocausto, César Hildebrandt Holocausto a debate, Henri Tincq Conferencia sobre el Holocausto, Thomas Erdbrink Sale el sol: es de noche, por Manuel Rodríguez Rivero ARMH pide que ley Memoria pene el 'negacionismo' de los crímenes franquistas Los palestinos, víctimas del holocausto y del negacionismo, Miguel Ángel Llana La religión cristiana y la Conferencia iraní sobre el Holocausto Carta abierta al Papa Benedicto XVl, Paul Grubach El yugo de Sión, Israel Adán Shamir ENTRE VICTORIA Y -

The Extreme Right in Contemporary Romania

INTERNATIONAL POLICY ANALYSIS The Extreme Right in Contemporary Romania RADU CINPOEª October 2012 n In contrast to the recent past of the country, there is a low presence of extreme right groups in the electoral competition of today’s Romania. A visible surge in the politi- cal success of such parties in the upcoming parliamentary elections of December 2012 seems to be unlikely. This signals a difference from the current trend in other European countries, but there is still potential for the growth of extremism in Roma- nia aligning it with the general direction in Europe. n Racist, discriminatory and intolerant attitudes are present within society. Casual intol- erance is widespread and racist or discriminatory statements often go unpunished. In the absence of a desire by politicians to lead by example, it is left to civil society organisations to pursue an educative agenda without much state-driven support. n Several prominent members of extreme right parties found refuge in other political forces in the last years. These cases of party migration make it hard to believe that the extreme views held by some of these ex-leaders of right-wing extremism have not found support in the political parties where they currently operate. The fact that some of these individuals manage to rally electoral support may in fact suggest that this happens precisely because of their original views and attitudes, rather than in spite of them. RADU CINPOEª | THE EXTREME RIGHT IN CONTEMPORARY ROMANIA Contents 1. Introduction. 3 2. Extreme Right Actors ...................................................4 2.1 The Greater Romania Party ..............................................4 2.2 The New Generation Party – Christian Democratic (PNG-CD) .....................6 2.3 The Party »Everything for the Country« (TPŢ) ................................7 2.4 The New Right (ND) Movement and the Nationalist Party .......................8 2.5 The Influence of the Romanian Orthodox Church on the Extreme Right Discourse .....8 3. -

The History of World Civilization. 3 Cyclus (1450-2070) New Time ("New Antiquity"), Capitalism ("New Slaveownership"), Upper Mental (Causal) Plan

The history of world civilization. 3 cyclus (1450-2070) New time ("new antiquity"), capitalism ("new slaveownership"), upper mental (causal) plan. 19. 1450-1700 -"neoarchaics". 20. 1700-1790 -"neoclassics". 21. 1790-1830 -"romanticism". 22. 1830-1870 – «liberalism». Modern time (lower intuitive plan) 23. 1870-1910 – «imperialism». 24. 1910-1950 – «militarism». 25.1950-1990 – «social-imperialism». 26.1990-2030 – «neoliberalism». 27. 2030-2070 – «neoromanticism». New history. We understand the new history generally in the same way as the representatives of Marxist history. It is a history of establishment of new social-economic formation – capitalism, which, in difference to the previous formations, uses the economic impelling and the big machine production. The most important classes are bourgeoisie and hired workers, in the last time the number of the employees in the sphere of service increases. The peasants decrease in number, the movement of peasants into towns takes place; the remaining peasants become the independent farmers, who are involved into the ware and money economy. In the political sphere it is an epoch of establishment of the republican system, which is profitable first of all for the bourgeoisie, with the time the political rights and liberties are extended for all the population. In the spiritual plan it is an epoch of the upper mental, or causal (later lower intuitive) plan, the humans discover the laws of development of the world and man, the traditional explanations of religion already do not suffice. The time of the swift development of technique (Satan was loosed out of his prison, according to Revelation 20.7), which causes finally the global ecological problems. -

1Daskalov R Tchavdar M Ed En

Entangled Histories of the Balkans Balkan Studies Library Editor-in-Chief Zoran Milutinović, University College London Editorial Board Gordon N. Bardos, Columbia University Alex Drace-Francis, University of Amsterdam Jasna Dragović-Soso, Goldsmiths, University of London Christian Voss, Humboldt University, Berlin Advisory Board Marie-Janine Calic, University of Munich Lenard J. Cohen, Simon Fraser University Radmila Gorup, Columbia University Robert M. Hayden, University of Pittsburgh Robert Hodel, Hamburg University Anna Krasteva, New Bulgarian University Galin Tihanov, Queen Mary, University of London Maria Todorova, University of Illinois Andrew Wachtel, Northwestern University VOLUME 9 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsl Entangled Histories of the Balkans Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies Edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover Illustration: Top left: Krste Misirkov (1874–1926), philologist and publicist, founder of Macedo- nian national ideology and the Macedonian standard language. Photographer unknown. Top right: Rigas Feraios (1757–1798), Greek political thinker and revolutionary, ideologist of the Greek Enlightenment. Portrait by Andreas Kriezis (1816–1880), Benaki Museum, Athens. Bottom left: Vuk Karadžić (1787–1864), philologist, ethnographer and linguist, reformer of the Serbian language and founder of Serbo-Croatian. 1865, lithography by Josef Kriehuber. Bottom right: Şemseddin Sami Frashëri (1850–1904), Albanian writer and scholar, ideologist of Albanian and of modern Turkish nationalism, with his wife Emine. Photo around 1900, photo- grapher unknown. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Entangled histories of the Balkans / edited by Roumen Daskalov and Tchavdar Marinov. pages cm — (Balkan studies library ; Volume 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

16–18. Századi Utazók, Utazások a 18

Bolti ár: 1100,- Ft Előfizetőknek: 1000,- Ft m á z 9 7 7 0 2 3 7 7 9 3 0 0 6 1 9 0 0 3 S . 3 . ETAS TÖRTÉNETTUDOMÁNYI FOLYÓIRAT 9 A 1 0 2 16–18. századi utazók, utazások A 18. század kétségkívül az utazások virágkorát jelentette a kora újkorban. A nagy háborúskodásokat követően tömegek indultak útnak a különféle társadalmi rétegekből. Az utazók sokszínűsé- KULCSÁR KRISZTINA géről tanúskodnak a nyomtatásban megjelent apodémikák, Ha főurak útra keltek… 18. századi főúri vagyis az utazás módszerét és technikáját tárgyaló, valamint az útnak indulók számára praktikus tanácsokat közlő művek. Egy utazástípusok Albert szász-tescheni herceg 1795-ben kiadott kézikönyv például a következő potenciális uta- zóközönséget sorolta fel: nemes ifjak, kertművészek, énekesek, és Mária Krisztina főhercegnő közös építészek, szobrászok, rézmetszők, festők, filológusok, filozófu- utazásai alapján sok, történészek, gazdasági szakemberek, matematikusok, ter- mészettudósok, orvosok, jogtudósok, teológusok, katonák, jö- vendőbeli követek, valamint leendő uralkodók és államférfiak – DINNYÉS PATRIK látható, hogy ők a társadalom bizonyos, leginkább tanulni vágyó rétegeit képviselik. Sokan öncélúan, saját ismereteiket kívánták Mogiljovtól Szmolenszkig: bővíteni (nemes ifjak, egyetemjárók, művészek, tudósok), má- II. József német-római császár és sok hivatalból vagy gyakorlati céllal utaztak (így kereskedők, mes- teremberek, katonák, hivatalnokok), és a 18. században többeket II. Katalin orosz császárnő első a kíváncsiság hajtott. Ám mellettük még mindig jelentős sze- találkozása és közös utazása (1780) repet játszottak az uralkodók, fejedelmek, hercegek. Ők már az ókortól kezdve fényűző utazásokat tettek udvaruk fényének eme- lésére és hatalmuk bizonyítására: birodalmukon belül az egyik OLGA KHAVANOVA városból a másikba utaztak, látványos bevonulásokkal, termé- szetesen a ceremoniális előírásokat betartva, népes udvari kísé- Pavel Petrovics orosz nagyherceg rettel. -

The Behavioural Dynamics of Romania's Foreign Policy In

THE BEHAVIOURAL DYNAMICS OF ROMANIA’S FOREIGN POLICY IN THE LATE 1990s: THE DRIVE FOR SECURITY AND THE POLITICS OF VOLUNTARY SERVITUDE Eduard Rudolf ROTH Abstract. This article investigates the nature, the magnitude and the impact of the exogenously articulated preferences in the articulation of Romania’s foreign policy agenda and behavioural dynamics during the period 1996-2000. In this context, the manuscript will explore Romania’s NATO and (to a lesser extent) EU accession bids, within an analytical framework defined by an overlapped interplay of heterochthonous influences, while trying to set out for further understanding how domestic preferences can act as a transmission belt and impact on foreign policy change in small and medium states. Keywords: Romanian foreign policy, NATO enlargement, EU enlargement, Russian-Romanian relations, Romanian-NATO relations, Romania-EU relations 1. Introduction By 1995 – with the last stages of the first Yugoslav crisis confirming that Moscow cannot adequately get involved into complex security equations – and fearing the possible creation of a grey area between Russia and Western Europe, Romanian authorities embarked the country on a genuinely pro-Western path, putting a de facto end to the dual foreign policy focus, “ambivalent policy”,1 “double speak”2 or “politics of ambiguity” 3 which dominated Bucharest’s’ diplomatic exercise throughout the early 1990s. This spectral shift (which arguably occurred shortly after Romanian President Iliescu’s visit in Washington) wasn’t however the result of a newly-found democratic vocation of the indigenous government, but rather an expression of the conviction that such behaviour could help the indigenous administration in its attempts to secure the macro-stabilization of the country’s unreformed economy and to acquire security guarantees in order to mitigate the effects of the political and geographical pressures generated by the Transdniestrian and Yugoslav conflicts, or by the allegedly irredentist undertones of Budapest’s foreign policy praxis. -

Borders of Trianon Had Been Determined on May 8, 1919, One Year Before the Signing of the Peace Treaty

FOREWORD The Peace Treaty of Trianon was Hungary’s turn of fate—a second Mohács. Hungary was compelled to sign it in one of the downturns of its history. Pál Teleki, the Prime Minister at that time who presented the peace treaty for parliamentary ratification, filed an indictment against himself in Parliament because he felt responsible... Recently, there has been increased interest concerning the Peace Treaty of Trianon. The subject of Trianon is inexhaustible. Nobody has yet written about Trianon in its complexity, and perhaps it will be long before anyone will. The subject is so complex that it must be studied from different angles, various scientific approaches, and using several methods. It remains unsettled, as its scholars can always discover new perspectives. This study - perhaps best described as a commentary - is not a scientific work. Rather, its goal is to enhance public awareness and offer a more current and realistic synthesis of the Peace Treaty of Trianon while incorporating more recent observations. Intended for a broad audience, its purpose is not to list historical events - as the historians have done and will continue to do - but rather to provide data regarding those geographic, economic and geo- political aspects and their correlation which have received inadequate attention in the literature on Trianon so far. Perhaps this work will also succeed in providing new perspectives. It is not as difficult to interpret and explain the text of the treaty as it is to write about and focus public attention on its spirit and its open and hidden aims. It is difficult - perhaps delicate - to write about its truths, how it really came about, and what effects it had on the Hungarian nation.