Scratch My Back, and I'll Scratch Yours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lead a Normal Life

1: Lead A Normal Life “My family arrived in this country from Spain at the time of the Armada, and the story goes we were adopted by Cornish peasants . .” Peter Gabriel, 1974 “My dad is an electrical engineer, inventor type, reserved, shy, analytical, and my mum’s more instinctive, she responds by the moment – music is her big thing. And I’ve got both.” Peter Gabriel, 2000 HEN Peter Gabriel spoke of rather trusting a ‘country man than a Wtown man’ in Genesis’ 1974 song ‘The Chamber Of 32 Doors’, he could well have been talking about his own roots. For in his 63 years (at the time of writing), Gabriel has spent less than a decade living in a city. Although he keeps a residence in West London, Gabriel lives in rustic splendour at his home by his Real World studios in Box near Bath in Wiltshire, which echoes the rural idyll of his childhood in the Surrey countryside. The physical roots of his life could be a metaphor for his semi-detached relationship with showbusiness; near enough, yet far away. Surrey is less than an hour from London and his residence now is less than 15 minutes from the bustling city centre of Bath. He can get into the middle of things easily when he needs to, yet he remains far enough removed. It is not dissimilar to his relationship with the mainstream of popular music. Whenever Gabriel has neared the big time (or indeed, ‘Big Time’, his 1986 hit single) he has been there just enough to receive acclaim and at times, stellar sales, before retreating back to the anonymous comfort of the margins. -

Heroes Magazine

HEROES ISSUE #01 Radrennbahn Weissensee a year later. The title of triumphant, words the song is a reference to the 1975 track “Hero” by and music. Producer Tony Visconti took credit for the German band Neu!, whom Bowie and Eno inspiring the image of the lovers kissing “by the admired. It was one of the early tracks recorded wall”, when he and backing vocalist Antonia Maass BOWIE during the album sessions, but remained (Maaß) embraced in front of Bowie as he looked an instrumental until towards the out of the Hansa Studio window. Bowie’s habit in end of production. The quotation the period following the song’s release was to say marks in the title of the song, a that the protagonists were based on an anonymous “’Heroes’” is a song written deliberate affectation, were young couple but Visconti, who was married to by David Bowie and Brian Eno in 1977. designed to impart an Mary Hopkin at the time, contends that Bowie was Produced by Bowie and Tony Visconti, it ironic quality on the protecting him and his affair with Maass. Bowie was released both as a single and as the otherwise highly confirmed this in 2003. title track of the album “Heroes”. A product romantic, even The music, co-written by Bowie and Eno, has of Bowie’s “Berlin” period, and not a huge hit in been likened to a Wall of Sound production, an the UK or US at the time, the song has gone on undulating juggernaut of guitars, percussion and to become one of Bowie’s signature songs and is synthesizers. -

Peter Gabriel L'uomo Che Vide Il Futuro Della Musica

38 Culture GIOVEDÌ 11 FEBBRAIO 2010 BUON COMPLEANNO p Auguri Sabato l’ex Genesis compie 60 anni e domani esce il nuovo cd, «Scratch My Back» p Sorprese Pezzi di Bowie, Talking Heads, Lou Reed ma anche Regina Spektor e Arcade Fire Peter Gabriel l’uomo che vide il futuro della musica Ancora una volta ha spiazzato que anni lasciò (di stucco) i Genesis e tutti. Gabriel compie 60 anni, e un’infinità di appassionati. li festeggia con un nuovo cd: so- Solo cover, questa volta, lui che lo orchestra per l’uomo che co- non ne aveva fatte quasi mai (gli ap- me nessun altro seppe reinven- passionati si dividono i bootleg con I tarsi quattro volte, reinventan- Heard it Through the Grapevine di do - ogni volta - la musica. Marvin Gaye o con Strawberry Fields dei Beatles...). Strane rivisitazioni: ROBERTO BRUNELLI una Heroes (sì, Bowie) che «disarma» Heroes tuffandola in un mare di archi [email protected] che ci ricordano una linea che parte Questa volta sono gli archi: insi- coltissima da Penderecki fino a lambi- nuanti, s’intrecciano dolorosamen- re Philip Glass, una Boy in the Bubble te nei meandri ignoti così come nel- di Paul Simon di cui sono decostruite l’intimo del vissuto musicale di tan- le intenzioni, come a dimostrare che ti di noi. Peter Gabriel da tempo im- la struttura s’impone sulla sovrastrut- memorabile ci ha abituato a improv- tura, che la composizione vince su visi mutamenti di scena. C’erano ogni orchestrazione possibile, e lo l’utopia dei fiori ed il blues, negli an- stesso vale per Apres Mois della giova- ni settanta, e lui si tuffa con i Gene- ne russa-americana Regina Spektor, sis in una terra di esplorazione in a malapena nata quando Peter era cui sul rock avevano preso a soffia- già al suo terzo album solista. -

Tolo Dictionary

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - No. 91 TOLO DICTIONARY by Susan Smith Crowley Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Crowley, S.S. Tolo dictionary. C-91, xiv + 129 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1986. DOI:10.15144/PL-C91.cover ©1986 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A - Occasional Papers SERIES B - Monographs SERIES C - Books SERIES D - Special Publications EDITOR: S.A. Wurm ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. W. Bender K.A. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics David Bradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii A. Capell P. MUhlhausler University of Sydney Linacre College, Oxford Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland K.J. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics U ni versity of Texas G.W. Grace Malcolm Ross University of Hawaii Australian National University M.A.K. Halliday Gillian Sankoff University of Sydney University of Pennsylvania E. Haugen W.A.L. Stokhof Harvard University University of Leiden A. Healey B.K. T'sou Summer Institute of Linguistics City Polytechnic of Hong Kong L.A. -

FORECAST – Skimming Off the Malware Cream

FORECAST – Skimming off the Malware Cream Matthias Neugschwandtner1, Paolo Milani Comparetti1, Gregoire Jacob2, and Christopher Kruegel2 1Vienna University of Technology, {mneug,pmilani}@seclab.tuwien.ac.at 2University of California, Santa Barbara, {gregoire,chris}@cs.ucsb.edu ABSTRACT Malware commonly employs various forms of packing and ob- To handle the large number of malware samples appearing in the fuscation to resist static analysis. Therefore, the most widespread wild each day, security analysts and vendors employ automated approach to the analysis of malware samples is currently based on tools to detect, classify and analyze malicious code. Because mal- executing the malicious code in a controlled environment to ob- ware is typically resistant to static analysis, automated dynamic serve its behavior. Dynamic analysis tools such as CWSandbox [3], analysis is widely used for this purpose. Executing malicious soft- Norman Sandbox and Anubis [13, 2] execute a malware sample in ware in a controlled environment while observing its behavior can an instrumented sandbox and record its interactions with system provide rich information on a malware’s capabilities. However, and network resources. This information can be distilled into a running each malware sample even for a few minutes is expensive. human-readable report that provides an analyst with a high level For this reason, malware analysis efforts need to select a subset of view of a sample’s behavior, but it can also be fed as input to fur- samples for analysis. To date, this selection has been performed ei- ther automatic analysis tasks. Execution logs and network traces ther randomly or using techniques focused on avoiding re-analysis provided by dynamic analysis have been used to classify malware of polymorphic malware variants [41, 23]. -

Peter Gabriel by W Ill Hermes

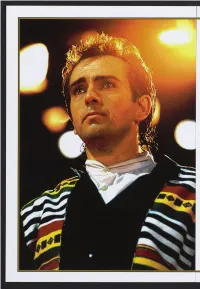

Peter Gabriel By W ill Hermes The multifaceted performer has spent nearly forty years as a solo artist and music innovator. THERE HAVE BEEN MANY PETER GABRIELS: THE PROG rocker who steered the cosmos-minded genre toward Earth; the sem i- new waver more focused on empathic storytelling and musical inno vation than fashion or attitude; the Top Forty hitmaker ambivalent about the spotlight; the global activist whose Real World label and collaborations introduced pivotal non-Western acts to new audiences; the elder statesman inspiring a new generation of singer-songwrit ers. ^ So his second induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, as a solo act this time - his first, in 2010, was as cofounder of the prog-pop juggernaut Genesis - seems wholly earned. Yet it surprised him, especially since he was a no-show that first time: The ceremony took place two days before the notorious perfectionist began a major tour. “I would’ve gone last time if I had not been about to perform,” Gabriel (b. February 13,1950) explained. “I just thought, 1 can’t go. We’d given ourselves very little rehearsal time.’” ^ “It’s a huge honor,” he said of his inclusions, noting that among numerous Grammys and other awards, this one is distinguished ‘because it’s more for your body of work than a specific project.” ^ That body of work began with Genesis, named after the young British band declined the moniker of “Gabriel’s Angels.” They produced their first single (“The Silent Sun”) in the winter of 1968, when Gabriel was 17. -

Symphony Orchestra and Wind Ensemble Present Peter Gabriel's

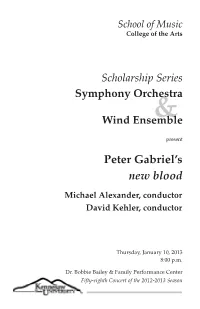

School of Music College of the Arts Scholarship Series Symphony Orchestra Wind Ensemble present Peter Gabriel’s new blood Michael Alexander, conductor David Kehler, conductor Thursday, January 10, 2013 8:00 p.m. Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center Fifty-eighth Concert of the 2012-2013 Season Kennesaw State University School of Music Audrey B. and Jack E. Morgan, Sr. Concert Hall January 10, 2013 Written by Peter Gabriel Arranged by John Metcalfe The Rhythm of the Heat Downside Up San Jacinto Intruder Wallflower In Your Eyes Mercy Street INTERMISSION Red Rain Darkness Don’t Give Up Digging In The Dirt The Nest That Sailed The Sky Solsbury Hill Published by: Real World Music Ltd / EMI Blackwoodwood Music Inc. Courtesy of petergabriel.com Personnel Flute/Alto Flute/Piccolo Violin 2 Catherine Flinchum, Woodstock Rachel Campbell, Sandy Springs Dirk Stanfield, Amarillo, TX Micah David, Portland, OR Amanda Esposito, Kennesaw Oboe Terry Keeling, Acworth Alexander Sifuentes, Lawrenceville Meian Butcher, Marietta Joshua Martin, Marietta Clarinet Kimberly Ranallo, Powder Springs Kadie Johnston, Buford Brittany Thayer, Burlington, VT Tyler Moore, Acworth Viola Bassoon Justin Brookins, Panama City, FL Sarah Fluker, Decatur Ryan Gibson, Marietta Hallie Imeson, Canton Horn Rachael Keplin, Wichita, KS David Anders, Kennesaw Kyle Mayes, Marietta Kristen Arvold, Cleveland Aliyah Miller, Austell Perry Morris, Powder Springs Alishia Pittman, Duluth Trumpet Samantha Tang, Marietta John Thomas Burson, Marietta Justin Rowan, Woodstock Cello Kathryn -

Support to Academics Who Are Carers in Higher Education

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article ‘You Scratch My Back and I’ll Scratch Yours’? Support to Academics Who Are Carers in Higher Education Marie-Pierre Moreau * and Murray Robertson School of Education and Social Care, Faculty of Health, Education, Medicine and Social Care, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge CB1 1PT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 April 2019; Accepted: 21 May 2019; Published: 29 May 2019 Abstract: In recent years, it has become common for individuals to juggle employment and unpaid care work. This is just as true for the England-based academic workforce, our focus in this article. We discuss how, in the context of English Higher Education, support for carers is enacted and negotiated through policies and practices of care. Our focus on academics with a diverse range of caring responsibilities is unusual insofar as the literature on care in academia is overwhelmingly concerned with parents, usually mothers. This article is informed primarily by critical and post-structuralist feminist perspectives. We draw on a corpus of 47 interviews conducted with academics representing a broad range of caring responsibilities, subjects, and positions. A thematic analysis reveals how carers’ relationship with the provision and policies of care support at an institutional level is characterised by ambivalence. On the one hand, participants approve of societal and institutional policy support for carers. On the other hand, they are often reluctant to position themselves as the beneficiary of such policies, expressing instead a general preference for support from outside the workplace or for workplace-based inter-individual and informal care arrangements. -

RAR Newsletter 111019.Indd

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 10/19/2011 Graffiti 6 “Free” #1 Most Added! BDS New & Active! FMQB Public Debut 48*! New: KMTT, WXRV, WNCS, WMWV, KSKI, WTMD, KMTN... ON: KBCO, KINK, WCLZ, KRVB, WNWV, KRSH, KCSN, WEHM, KKXT, WEXT, DMX Adult Alternative, KROK, WVMP... EP (out now) features many stripped down tracks, full cd Colours in January One of the top-scoring tracks at the Rate-A-Record in Boulder Ben Lee “Get Used To It” The first single from Deeper Into Dream, in stores and going for adds now! Lots of great press already New: SiriusXM Loft, WFIV, WJCU, DMX Adult Alternative, KXCI, WERU, WDIY Early: WEHM, KBAC, WWCT, WYCE, WBJB, WBSD... “Deeper Into Dream shows incredible growth in Lee and an exciting new direction to his usual style.” - Paste Magazine Peter Gabriel - New Blood (album) Most added! New: WMVY, WMWV, WEHM, KTBG, Acoustic Cafe, MSPR, KVNF Two edits available on PlayMPE ON: Sirius Spectrum, WFUV, KCMP, WVMP, KOZT, WFIV, KSUT, KFMG, KLCC... An amazing take on his hits In stores now, tons of amazing press already! Companion live DVD hits stores on Tuesday Full cd on your desk Beth Hart & Joe Bonamassa “Well, Well” BDS Indicator Debut 29*! FMQB Tracks 26*! Public 33*! New: KPIG, KXCI ON: SiriusXM Loft, KPND, KRSH, KCSN, WXPN, WFPK, WFIV, WDST, WTMD, WKZE, KYSL, WEXT, WMVY, WCBE, KMTN, KFMU, KSPN, KOZT, WJCU... Don’t Explain in stores now! Many of Joe Bonamassa’s upcoming tour dates are close to selling out weeks in -

The Peter Vickers Genesis Collection Wednesday 16Th May 2018 at 10.00

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) The Peter Vickers Genesis Collection Wednesday 16th May 2018 at 10.00 Viewing: 14th May 10.00-16.00 For enquiries relating to the auction 15th May 2018 09:00 - 16:00 please contact: 09:00 morning of auction Otherwise by Appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 David Martin Fax: 0871 714 6905 Music & Email: [email protected] Entertainment www.specialauctionservices.com As per our Terms and Conditions and with particular reference to autograph material or works, it is imperative that potential buyers or their agents have inspected pieces that interest them to ensure satisfaction with the lot prior to the auction; the purchase will be made at their own risk. Special Auction Services will give indica- tions of provenance where stated by vendors. Subject to our normal Terms and Conditions, we cannot accept returns. Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price The Peter Vickers Genesis Collection Peter Vickers started collecting Genesis Records and Memorabilia in the Mid 1970s and became a well known and respected member of the Genesis fan community, writing a number of articles on the band for magazines and on line. Peter also self produced several limited edition books on the history of Genesis and Rare Collectibles. It is doubtful if anyone else had the depth and breadth of his knowledge regarding the Band’s Recorded output around the world. -

Illerite IHAPLIN Knickerbocker \

* « j Theaters W jiurnky gfct J Automobiles J Part 3.12 PagesWASHINGTON, D. C., SUNDAY MORNING, JULY 11, 1920. isemfiflts % ffvn j\0 Theater a*i Photoplay AMERICA showed the old world *audeville, and first-run motion Billie Richmond with Mauricepictire!--. besides brave, res- something j ,a Mar, Marie Parker and the xlls: __ olute. daring heroism in the ti Jazz Four, will present an eccenricact of ^i(^|^HHpr erreat world war ITer sturdv. ! 31ongs, tiauce specialties and jazz. ^jgMg I ° o feature will be George Randall Anhterand bronzed heroes in khaki carried with 0ompany in a sketch entitled, "Too them the punch and the strength to Elasy." Others will include Herras and "put it not 'reston, spectacular gy mnasts; Mabel over," and it did surprise ^nd Johnny Dove, "The Camouflage the folks at home when they quickly j>uo," in darktown I / laughable specialties; ijj^y r*'' n A took their rank with the bravest and a nd Fox and Mayo, melodists with a *^"ij ^^ (^i ^ri j best troops of the militaristic erlse of humor. Edgar Lewis' special roiuction for Pathe, "Other Men's Cvmw&nAtA of Europe. But she showed countriesmore ghoes." featuring Craufurd Kent, will ,N even than that, a something that is be shown at all performances, and just as essential to the world's well irlinor films will be added at the f||p being as physical strength and cour- n:latinees. * age. She showed the people of the 1 -' -. continent that her men are clean, Steamer St. Johns. ifiL I«S1 BSk1 w -i ^w^Snim«*4- manly men. -

TRINITY LUTHERAN CHURCH 12 SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST PASTOR NICK DROGE SEPTEMBER 1, 2019 “WHERE DO I SIT?” LUKE 14:1, 7-14 Last

TRINITY LUTHERAN CHURCH 12TH SUNDAY AFTER PENTECOST PASTOR NICK DROGE SEPTEMBER 1, 2019 “WHERE DO I SIT?” LUKE 14:1, 7-14 Last Sunday, my wife’s family — her mom, her dad, her step-sister and brother-in-law from Bakersfield; my wife’s kids and her grandkids gathered for dinner at my in-laws’ to celebrate my wife’s birthday. Her birthday was actually this past Wednesday, but of course it’s much more practical to gather on a weekend rather than to gather in the middle of the week. Her oldest son flew in from Utah as a surprise, and it was; it was a really pleasant surprise, a surprise that kept on giving; because she got up at 4:00 Monday morning to take him back to the airport. You might be thinking I should have been a good guy. I should have offered to get up in the middle of the night Monday morning and take him to the airport. Yeah, well I’m not a good guy. Her son’s been living in Texas for the past two years and she doesn’t get to see him that often. So that drive to the airport at 4am Monday gave them an opportunity to spend some alone time together. I suppose I could have been a good guy and offered to go along to the airport with them so she wouldn’t have to drive home alone. But remember, I’m not a good guy. Back to that dinner at my in-laws last Sunday. My wife’s parents are both in their early eighties and they moved to Fresno from Coarsegold almost two years ago, downsizing their home considerably.