A Death Foretold, P. 36

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abbreviations

Abbreviations A1B One of the IPCC SRES scenarios AIS Asociación Colombiana de Ingeniería ABM anti-ballistic missile Sísmica [Colombian Association for AA Auswärtiges Amt [Federal Ministry for Earthquake Engineering] Foreign Affairs, Germany] AKOM Afet Koordinasyon Merkezi [Istanbul ACOTA African Contingency Operations Training Metropolitan Municipality Disaster Assistance Coordination Centre] ACRS Arms Control and Regional Security AKP Adalet ve Kalkinma Partisi [Justice and ACSAD Arab Center for the Studies of Arid Zones Development Party] and Dry Lands AKUF AG Kriegsursachenforschung [Study Group ACSYS Arctic Climate System Study on the Causes of War] (at Hamburg ACUNU American Council for the United Nations University) University AL Arab League AD anno domini [after Christ] AMMA African Monsoon Multidisciplinary Analysis ADAM Adaptation and Mitigation Strategies: Project Supporting European Climate Policy (EU AMU Arab Maghreb Union funded project) An. 1 Annex 1 countries (under UNFCCC) ADB Asian Development Bank An. B Annex B countries (under Kyoto Protocol) ADRC Asian Disaster Reduction Centre ANAP Anavatan Partisi [Motherland Party] AESI Asociación Española de Ingeniría Sísmica ANU Australian National University [Association for Earthquake Engineering of AOSIS Alliance of Small Island States Spain] AP3A Early Warning and Agricultural Productions AfD African Development Bank Forecasting, project of AGRHYMET AFD Agence Française de Développement APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation AFED Arab Forum on Environment and APHES Assessing -

Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tracing the Genetic Diversity of Brucella Abortus and Brucella Melitensis Isolated from Livestock in Egypt

pathogens Article Whole-Genome Sequencing for Tracing the Genetic Diversity of Brucella abortus and Brucella melitensis Isolated from Livestock in Egypt Aman Ullah Khan 1,2,3 , Falk Melzer 1, Ashraf E. Sayour 4, Waleed S. Shell 5, Jörg Linde 1, Mostafa Abdel-Glil 1,6 , Sherif A. G. E. El-Soally 7, Mandy C. Elschner 1, Hossam E. M. Sayour 8 , Eman Shawkat Ramadan 9, Shereen Aziz Mohamed 10, Ashraf Hendam 11 , Rania I. Ismail 4, Lubna F. Farahat 10, Uwe Roesler 2, Heinrich Neubauer 1 and Hosny El-Adawy 1,12,* 1 Institute of Bacterial Infections and Zoonoses, Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, 07743 Jena, Germany; AmanUllah.Khan@fli.de (A.U.K.); falk.melzer@fli.de (F.M.); Joerg.Linde@fli.de (J.L.); Mostafa.AbdelGlil@fli.de (M.A.-G.); mandy.elschner@fli.de (M.C.E.); Heinrich.neubauer@fli.de (H.N.) 2 Institute for Animal Hygiene and Environmental Health, Free University of Berlin, 14163 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 3 Department of Pathobiology, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences (Jhang Campus), Lahore 54000, Pakistan 4 Department of Brucellosis, Animal Health Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Dokki, Giza 12618, Egypt; [email protected] (A.E.S.); [email protected] (R.I.I.) 5 Central Laboratory for Evaluation of Veterinary Biologics, Agricultural Research Center, Abbassia, Citation: Khan, A.U.; Melzer, F.; Cairo 11517, Egypt; [email protected] 6 Sayour, A.E.; Shell, W.S.; Linde, J.; Department of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Zagazig University, Elzera’a Square, Abdel-Glil, M.; El-Soally, S.A.G.E.; Zagazig 44519, Egypt 7 Veterinary Service Department, Armed Forces Logistics Authority, Egyptian Armed Forces, Nasr City, Elschner, M.C.; Sayour, H.E.M.; Cairo 11765, Egypt; [email protected] Ramadan, E.S.; et al. -

Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future

Economy Suez Canal Development Project: Egypt's Gate to the Future President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi With the Egyptian children around him, when he gave go ahead to implement the East Port Said project On November 27, 2015, President Ab- Egyptians’ will to successfully address del-Fattah el-Sissi inaugurated the initial the challenges of careful planning and phase of the East Port Said project. This speedy implementation of massive in- was part of a strategy initiated by the vestment projects, in spite of the state of digging of the New Suez Canal (NSC), instability and turmoil imposed on the already completed within one year on Middle East and North Africa and the August 6, 2015. This was followed by unrelenting attempts by certain interna- steps to dig out a 9-km-long branch tional and regional powers to destabilize channel East of Port-Said from among Egypt. dozens of projects for the development In a suggestive gesture by President el of the Suez Canal zone. -Sissi, as he was giving a go-ahead to This project is the main pillar of in- launch the new phase of the East Port vestment, on which Egypt pins hopes to Said project, he insisted to have around yield returns to address public budget him on the podium a galaxy of Egypt’s deficit, reduce unemployment and in- children, including siblings of martyrs, crease growth rate. This would positively signifying Egypt’s recognition of the role reflect on the improvement of the stan- of young generations in building its fu- dard of living for various social groups in ture. -

1 Peter I of Alexandria Coptic Fragment Anthony Alcock

1 Peter I of Alexandria Coptic fragment Anthony Alcock The fragment in question was catalogued by É. Amélineau in his Catalogue des Mss coptes (1889) and first published by Carl Schmidt as 'Fragmente einer Schrift des Märtyerbischofes von Alexandrien' in Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur 20 (1901) fasc. 4 pp. 50ff. Peter I was the 17th Patriarch of the Egyptian Church from 300 to 311. He had held office for three years before the Great Persecution began. During his patriarchate there was an internal threat to the Church from Arius and Meletius, the former on doctrinal grounds, the latter on ecclesiastical political grounds1 and the external one known as the Diocletianic or Great Persecution, which broke out in 303 and came to an end in 311. Peter spent several of his patriarchal years hiding from the persecution and was finally executed in 311.2 The organization of the text does not make for easy reading, and I have decided to copy it as a continuous horizontally-oriented text, each page followed by the English version, so that anyone who wishes can consult both text and translation with ease. This after all is not a work of scholarship,3 but, I hope, one that will be useful to those with a casual interest in the language and church history. The text is from a 9th cent. White Monastery library codex and is now in Paris, where it bears the inventory number Paris copte 1305 fols. 123ff. It is written in the 1st person, either as a sermon or a letter: the speaker identifies himself as Peter (p. -

The Holy Psalmody of Kiahk Published by St

HOLY PSALMODY OF Kiahk According to the orders of the Coptic Orthodox Church First Edition }"almwdi8a Ecouab 8nte pi8abot ak <oi 8M8vrh+ 8etaucass 8nje nenio+ 8n+ek8klhsi8a 8nrem8n<hmi M St. George & St. Joseph Coptic Orthodox Church K The Holy Psalmody of Kiahk Published by St. George and St Joseph Church Montreal, Canada Kiahk 1724 A. M., December 2007 A. D. St George & St Joseph Church 17400 Boul. Pierrefonds Pierrefonds, QC. CANADA H9J 2V6 Tel.: (514) 626‐6614, Fax.: (514) 624‐8755 http://www.stgeorgestjoseph.ca Behold, from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed. For he that is mighty hath done to me great things; and holy is His Name. Luke 1: 48 - 49 Hhppe gar isjen +nou senaermakarizin 8mmoi 8nje nigene8a throu@ je afiri nhi 8nxanmecnis+ 8nje vh etjor ouox 8fouab 8nje pefran. His Holiness Pope Shenouda III Pope of Alexandria, and Patriarch of the see of saint Mark Peniwt ettahout 8nar,hepiskopos Papa abba 0enou+ nimax somt Preface We thank the Lord, our God and Saviour, for helping us to start this project. In this first edition, our goal was to gather pre‐translated hymns, and combine them with Midnight Praises in one book. God willing, our final goal is to have one book where the congregation can follow all the proceedings without having to refer to numerous other sources. We ask and pray to our Lord to help us complete this project in the near future. The translated material in this book was collected from numerous sources: Coptichymns.net web site Kiahk Praises, by St George & St Shenouda Church The Psalmody of Advent, by William A. -

Suez Canal University Cardiology Department

Curriculum Vitae Personal Data Name: GAMELA MOHAMMED ALI AHMED NASR Nationality: Egyptian Marital status: Married Sex: Female Address: Heliopolis, Cairo, Egypt. Telephone: (202) 4192178 Cellular: 00201001904702 Fax : (202) 2919694 E-Mail: [email protected] Academic Qualification B.SC. Medicine and Surgery, Assuit University, Egypt, Very Good with honour Feb 1987. M.SC. General Medicine and Cardiology, Department of General Medicine, Assuit University, Egypt, very good. The thesis was entitled "Non invasive assessment Of cardiac functions in diabetics , July 1992 MD Cardiology, Department of Cardiology, Suez Canal University, Egypt. The Thesis was entitled "Value Of Enhanced Technetium–99m Sestamibi Scans with nitroglycerine in comparison with Thallium–201 for detecting Myocardial Viability", April 2000. Current Position • Professor of Cardiology at Cardiology Department, Suez Canal University - Egypt • Vice president of the Egyptian Society of Cardiology • Head of working group for cardiovascular disease prevention and cardiac rehabilitation of the Egyptian Society of Cardiology and its representative for the European Society of cardiology for prevention and education • Member of the Egyptian council for women • Consultant of Cardiology at National Hospital for Insurance. Nasr City, Cairo, Egypt and for Suez Canal area Ismailia . • Consultant of Cardiology at National medical sporting center at Cairo • Member of Specialized National committee – Health sector • Consultant of Cardiology and Echocardiography at Suez Canal Authority • Member of Scientific Council of Egyptian Fellowship for Cardiovascular Medicine • Member of Accreditation board of Egyptian Fellowship for Cardiovascular Medicine • Member of Scientific Council of Egyptian Fellowship for Critical Care Medicine 1 • Head of scientific committee for first professional diploma for echocardiography • Member of Egyptian – American Scolars Association • Member of European society of Cardiology • Member of the Working Group of Nuclear Cardiology, Egypt. -

Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

Submitted to : Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL Prepared by: IMPACT ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK Executive Summary EcoConServ Environmental Solutions 12 El-Saleh Ayoub St., Zamalek, Cairo, Egypt 11211 NATURAL GAS CONNECTION PROJECT Tel: + 20 2 27359078 – 2736 4818 IN 11 GOVERNORATES IN EGYPT Fax: + 20 2 2736 5397 E-mail: [email protected] (Final March 2014) Executive Summary ESIAF NG Connection 1.1M HHs- 11 governorates- March 2014 List of acronyms and abbreviations AFD Agence Française de Développement (French Agency for Development) AP Affected Persons ARP Abbreviated Resettlement Plan ALARP As Low As Reasonably Practical AST Above-ground Storage Tank BUTAGASCO The Egyptian Company for LPG distribution CAA Competent Administrative Authority CULTNAT Center for Documentation Of Cultural and Natural Heritage CAPMAS Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics CDA Community Development Association CRN Customer Reference Number EDHS Egyptian Demographic and Health Survey EHDR Egyptian Human Development Report 2010 EEAA Egyptian Environmental Affairs Agency EGAS Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMU Environmental Management Unit ENIB Egyptian National Investment Bank ES Environmental and Social ESDV Emergency Shut Down Valve ESIAF Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Framework ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMMF Environmental and Social Management and Monitoring Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FGD Focus Group Discussion -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

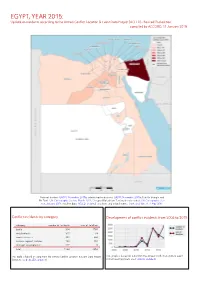

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Service Books of the Orthodox Church

SERVICE BOOKS OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. BASIL THE GREAT THE LITURGY OF THE PRESANCTIFIED GIFTS 2010 1 The Service Books of the Orthodox Church. COPYRIGHT © 1984, 2010 ST. TIKHON’S SEMINARY PRESS SOUTH CANAAN, PENNSYLVANIA Second edition. Originally published in 1984 as 2 volumes. ISBN: 978-1-878997-86-9 ISBN: 978-1-878997-88-3 (Large Format Edition) Certain texts in this publication are taken from The Divine Liturgy according to St. John Chrysostom with appendices, copyright 1967 by the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, and used by permission. The approval given to this text by the Ecclesiastical Authority does not exclude further changes, or amendments, in later editions. Printed with the blessing of +Jonah Archbishop of Washington Metropolitan of All America and Canada. 2 CONTENTS The Entrance Prayers . 5 The Liturgy of Preparation. 15 The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom . 31 The Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great . 101 The Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. 181 Appendices: I Prayers Before Communion . 237 II Prayers After Communion . 261 III Special Hymns and Verses Festal Cycle: Nativity of the Theotokos . 269 Elevation of the Cross . 270 Entrance of the Theotokos . 273 Nativity of Christ . 274 Theophany of Christ . 278 Meeting of Christ. 282 Annunciation . 284 Transfiguration . 285 Dormition of the Theotokos . 288 Paschal Cycle: Lazarus Saturday . 291 Palm Sunday . 292 Holy Pascha . 296 Midfeast of Pascha . 301 3 Ascension of our Lord . 302 Holy Pentecost . 306 IV Daily Antiphons . 309 V Dismissals Days of the Week . -

Is Perpetrated by Fundamentalist Sunnis, Except Terrorism Against Israel

All “Islamic Terrorism” Is Perpetrated by Fundamentalist Sunnis, Except Terrorism Against Israel By Eric Zuesse Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, June 10, 2017 Theme: Terrorism, US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: IRAN: THE NEXT WAR?, IRAQ REPORT, SYRIA My examination of 54 prominent international examples of what U.S.President Donald Trump is presumably referring to when he uses his often-repeated but never defined phrase “radical Islamic terrorism” indicates that it is exclusively a phenomenon that is financed by the U.S. government’s Sunni fundamentalist royal Arab ‘allies’ and their subordinates, and not at all by Iran or its allies or any Shiites at all. Each of the perpetrators was either funded by those royals, or else inspired by the organizations, such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, that those royals fund, and which are often also armed by U.S.-made weapons that were funded by those royals. In other words: the U.S. government is allied with the perpetrators. Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani and Syrian counterpart Bashar al-Assad (Source: antiliberalnews.net) See the critique of this article by Kevin Barrett Stop the Smear Campaign (and Genocide) Against Sunni Islam!By Kevin Barrett, June 13, 2017 Though U.S. President Donald Trump blames Shias, such as the leaders of Iran and of Syria, for what he calls “radical Islamic terrorism,” and he favors sanctions etc. against them for that alleged reason, those Shia leaders and their countries are actually constantly being attacked by Islamic terrorists, and this terrorism is frequently perpetrated specifically in order to overthrow them (which the U.S. -

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development By Dr. Hamed Korkor Chairman Assistant Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS United Nations – Economic Commission for Europe Working Party on Gas 17th annual Meeting Geneva, Switzerland January 23-24, 2007 Egyptian Natural Gas Industry History EarlyEarly GasGas Discoveries:Discoveries: 19671967 FirstFirst GasGas Production:Production:19751975 NaturalNatural GasGas ShareShare ofof HydrocarbonsHydrocarbons EnergyEnergy ProductionProduction (2005/2006)(2005/2006) Natural Gas Oil 54% 46 % Total = 71 Million Tons 26°00E 28°00E30°00E 32°00E 34°00E MEDITERRANEAN N.E. MED DEEPWATER SEA SHELL W. MEDITERRANEAN WDDM EDDM . BG IEOC 32°00N bp BALTIM N BALTIM NE BALTIM E MED GAS N.ALEX SETHDENISE SET -PLIOI ROSETTA RAS ELBARR TUNA N BARDAWIL . bp IEOC bp BALTIM E BG MED GAS P. FOUAD N.ABU QIR N.IDKU NW HA'PY KAROUS MATRUH GEOGE BALTIM S DEMIATTA PETROBEL RAS EL HEKMA A /QIR/A QIR W MED GAS SHELL TEMSAH ON/OFFSHORE SHELL MANZALAPETROTTEMSAH APACHE EGPC EL WASTANI TAO ABU MADI W CENTURION NIDOCO RESTRICTED SHELL RASKANAYES KAMOSE AREA APACHE Restricted EL QARAA UMBARKA OBAIYED WEST MEDITERRANEAN Area NIDOCO KHALDA BAPETCO APACHE ALEXANDRIA N.ALEX ABU MADI MATRUH EL bp EGPC APACHE bp QANTARA KHEPRI/SETHOS TAREK HAMRA SIDI IEOC KHALDA KRIER ELQANTARA KHALDA KHALDA W.MED ELQANTARA KHALDA APACHE EL MANSOURA N. ALAMEINAKIK MERLON MELIHA NALPETCO KHALDA OFFSET AGIBA APACHE KALABSHA KHALDA/ KHALDA WEST / SALLAM CAIRO KHALDA KHALDA GIZA 0 100 km Up Stream Activities (Agreements) APACHE / KHALDA CENTURION IEOC / PETROBEL -

De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula

Policy Briefing April 2017 De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz De-Securitizing Counterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha III De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz1 On October 22, 2016, a senior Egyptian army ideal location for lucrative human, drug, and officer was killed in broad daylight outside his weapons smuggling (much of which now home in a Cairo suburb.2 The former head of comes from Libya), and for militant groups to security forces in North Sinai was allegedly train and launch terrorist attacks against both murdered for demolishing homes and