Notes on Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyra Mckee 31 March, 1990 – 18 April, 2019 Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | MAY-JUNE 2019 Lyra McKee 31 March, 1990 – 18 April, 2019 Contents Main feature 16 The writing’s on the wall Exposing a news vacuum News t’s not often that an event shakes our 03 Tributes mark loss of Lyra McKee profession, our union and society as powerfully as the tragic death of Lyra McKee. Widespread NUJ vigils A young, inspirational journalist from 04 Union backs university paper Belfast, lost her life while covering riots Ethics council defends standards Iin the Creggan area of Derry. Lyra became a journalist in the post peace agreement era 05 TUC women’s conference in Northern Ireland and in many ways was a symbol of the Calls for equal and opportunities new Ireland. She campaigned for Northern Ireland’s LGBTQ 07 Honouring Lyra community and used her own coming out story to support Photo spread others. She was a staunch NUJ member and well known in her Belfast branch. “At 29 she had been named as one of 30 European journalists Features under 30 to watch. She gave a prestigious Ted talk two years 10 A battle journalism has to win ago following the Orlando gay nightclub shootings in 2016. She Support for No Stone Unturned pair had signed a two-book deal with Faber with the first book about children and young men who went missing in the Troubles due 12 Only part of the picture out next year. How ministers control media coverage The NUJ has worked with the family to create a fund 22 Collect your royal flush in Lyra’s name and the family said that they have been How collecting societies help freelances inundated with requests to stage events in her name. -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

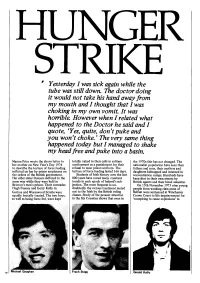

Article on Hungerstrike

" Yesterday I was sick again while the tube was still down. The doctor doing it would not take his hand away [rom my mouth and I thought that I was choking in my own vomit. It was homble. However when I related what happened to the Doctor he said and I quote, 'Yes, quite, don'tpuke and you won't choke. ' The very same thing happened today but I managed to shake my head [ree and puke into a basin. Marian Price wrote the above letter to totaHy naked in their ceHs in solitary the 1970s this has not changed. The her mother on New Year's Day 1974 confinement as a punishment for their nationalist population have seen their to describe the torture of force feeding refusal to wear prison uniform. The fathers and sons, their mothers and inflicted on her by prison employees on torture of force feeding lasted 166 days. daughters kidnapped and interned in the orders of the British government. Students of Irish history over the last concentration camps. Hundreds have Her eIder sister Dolours suffered in the 800 years have noted many constant been shot in their own streets by same way while they were held in trends in each epoch of Ireland's sub• British agents and their hired assassins. Brixton's men's prison. Their comrades jection. The most frequent is un• On 15th November 1973 nine young Hugh Feeney and Gerry KeHy in doubtedly the vicious treatment meted people from working class areas of Gartree and Wormwood Scrubs were out to the Irish by the British ruling Belfast were sentenced at Winchester equally brutally treated. -

The Path to Revolutionary Violence Within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA

The Path to Revolutionary Violence within the Weather Underground and Provisional IRA Edward Moran HIS 492: Seminar in History December 17, 2019 Moran 1 The 1960’s was a decade defined by a spirit of activism and advocacy for change among oppressed populations worldwide. While the methods for enacting change varied across nations and peoples, early movements such as that for civil rights in America were often committed to peaceful modes of protest and passive resistance. However, the closing years of the decade and the dawn of the 1970’s saw the patterned global spread of increasingly militant tactics used in situations of political and social unrest. The Weather Underground Organization (WUO) in America and the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) in Ireland, two such paramilitaries, comprised young activists previously involved in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association (NICRA) respectively. What caused them to renounce the non-violent methods of the Students for a Democratic Society and the Northern Irish Civil Rights Association for the militant tactics of the Weather Underground and Irish Republican Army, respectively? An analysis of contemporary source materials, along with more recent scholarly works, reveals that violent state reactions to more passive forms of demonstration in the United States and Northern Ireland drove peaceful activists toward militancy. In the case of both the Weather Underground and the Provisional Irish Republican Army in the closing years of the 1960s and early years of the 1970s, the bulk of combatants were young people with previous experience in more peaceful campaigns for civil rights and social justice. -

La Mon Atrocity Remembered a Memorial Service Has Been Held In

::: u.tv ::: NEWS Body found at Grand Canal SUNDAY Confidential files found at roadside 17/02/2008 18:05:01 Jobs boost for Cork Two 'critical' after attack La Mon atrocity remembered War of words 09:39 A memorial service has been held in Belfast to 09:20 New crime crackdown launched mark the 30th anniversary of the La Mon hotel Atrocity is remembered Man held after 'sex attack' bombing. La Mon atrocity remembered Relatives of the 12 people killed in the 1978 IRA atrocity gathered at Two held after Moira assault Castlereagh Council offices this afternoon for a service of remembrance Three held after drugs find led by the Rev David McIlveen. Limavady fire is 'suspicious' Man dies after Galway crash The DUP`s Irish Robinson and Jimmy Spratt were also among those Brendan Hughes has died attending the service today. Petrol bomb attack in Cullybackey Charge after Belfast death Disruption to Dublin Airport flights The event follows criticism of the DUP from some of the La Mon families who have accused Ian Paisley of letting victims down by going into Cannabis seeds found in Moy government with Sinn Fein. Man dies after Carlow RTC Charges after Portadown attack Two held after drugs seizure More than 400 people were attending a dinner dance in La Mon, when the IRA incendiary device went off. Man stabbed in Sligo Man 'critical' after Dublin assault Bluetongue confirmed in NI A wreath was laid at the La Mon garden in the council grounds today in Donegal murder victim laid to rest memory of the seven women and five men who were killed in one of the worst attacks of the Troubles. -

Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980S Irish Theatre

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Provoking performance: challenging the people, the state and the patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Author(s) O'Beirne, Patricia Publication Date 2018-08-28 Publisher NUI Galway Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/14942 Downloaded 2021-09-27T14:54:59Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre Candidate: Patricia O’Beirne Supervisor: Dr. Ian Walsh School: School of Humanities Discipline: Drama and Theatre Studies Institution: National University of Ireland, Galway Submission Date: August 2018 Summary of Contents: Provoking Performance: Challenging the People, the State and the Patriarchy in 1980s Irish Theatre This thesis offers new perspectives and knowledge to the discipline of Irish theatre studies and historiography and addresses an overlooked period of Irish theatre. It aims to investigate playwriting and theatre-making in the Republic of Ireland during the 1980s. Theatre’s response to failures of the Irish state, to the civil war in Northern Ireland, and to feminist and working-class concerns are explored in this thesis; it is as much an exploration of the 1980s as it is of plays and playwrights during the decade. As identified by a literature review, scholarly and critical attention during the 1980s was drawn towards Northern Ireland where playwrights were engaging directly with the conflict in Northern Ireland. This means that proportionally the work of many playwrights in the Republic remains unexamined and unpublished. -

Oral Evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 157

Northern Ireland Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Brexit and the Northern Ireland Protocol, HC 157 Wednesday 9 June 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 9 June 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Simon Hoare (Chair); Scott Benton; Mr Gregory Campbell; Stephen Farry; Mr Robert Goodwill; Claire Hanna; Fay Jones; Ian Paisley; Bob Stewart. Questions 919 - 940 Witnesses II: Susan McKay, Journalist and Author. Examination of witness Witness: Susan McKay. Q919 Chair: Let us now turn to Susan McKay. Good morning. Thank you for joining us. Ms McKay, you recently published a book—other authors are available—Northern Protestants: On Shifting Ground; it was published last month. What is your take? What is the rub? What is the actual issue here? What is the beef? Susan McKay: Thank you, Mr Chair. That is an extraordinary question in its breadth. One of the reasons why I wrote the book is that I am from the Protestant community myself in Northern Ireland, from Derry, and I have been working as a journalist, mainly in Northern Ireland, for the last 30 years. Over that time I have observed that there is an immense variety and diversity of people within the Protestant, loyalist and unionist communities and I felt that that was not widely enough recognised. For example, when we talk of loyalists, people often conflate the idea of loyalists with loyalist paramilitaries, which is so wrong. The loyalist community is extremely diverse. It includes people who vote for the unionist parties; it also includes people who vote for other non-unionist parties and many people who do not vote at all. -

Appendix List of Interviews*

Appendix List of Interviews* Name Date Personal Interview No. 1 29 August 2000 Personal Interview No. 2 12 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 3 18 September 2000 Personal Interview No. 4 6 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 5 16 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 6 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 7 18 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 8: Oonagh Marron (A) 17 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 9: Oonagh Marron (B) 23 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 10: Helena Schlindwein 28 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 11 30 October 2000 Personal Interview No. 12 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 13 1 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 14: Claire Hackett 7 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 15: Meta Auden 15 November 2000 Personal Interview No. 16 1 June 2000 Personal Interview Maggie Feeley 30 August 2005 Personal Interview No. 18 4 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 19: Marie Mulholland 27 August 2009 Personal Interview No. 20 3 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21A (joint interview) 23 February 2010 Personal Interview No. 21B (joint interview) 23 February 2010 * Locations are omitted from this list so as to preserve the identity of the respondents. 203 Notes 1 Introduction: Rethinking Women and Nationalism 1 . I will return to this argument in a subsequent section dedicated to women’s victimisation as ‘women as reproducers’ of the nation. See also, Beverly Allen, Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1996); Alexandra Stiglmayer, (ed.), Mass Rape: The War Against Women in Bosnia- Herzegovina (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1994); Carolyn Nordstrom, Fieldwork Under Fire: Contemporary Studies of Violence and Survival (Berkeley: University of California, 1995); Jill Benderly, ‘Rape, feminism, and nationalism in the war in Yugoslav successor states’ in Lois West, ed., Feminist Nationalism (London and New Tork: Routledge, 1997); Cynthia Enloe, ‘When soldiers rape’ in Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives (Berkeley: University of California, 2000). -

Irish Journalist Summer 2021.Pdf

1 THE IRISH JOURNALIST Newsletter of the National Union of Journalists in Ireland Summer 2021 Journalist Lyra McKee will be remembered on Thursday at a special event in the lead-up to DM weekend. Last month, Derry council buildings, including City of Derry Airport, the council offices and the Guildhall were lit in rainbow colours to celebrate Lyra's life and mark the two-year anniversary of her tragic murder. (See page 4). Online DM key to the future By Séamus Dooley, Irish Secretary union’s response to the Covid crisis, featuring Future The multiple challenges facing the NUJ will be of Media Commission member Siobhan Holliman. brought into sharp focus at the union’s first ever Thursday’s public service broadcasting commission online delegate meeting on May 21st and 22nd. will hear from a diverse range of speakers, including Irish language producer and RTÉ Trade Union Group DM 2021 takes place against the backdrop of the Secretary Cearbhall Ó Síocháin. global Covid-19 pandemic, which has had a At 6.30pm on Thursday night, the NUJ will catastrophic impact on the media across all remember Lyra McKee with a special panel platforms. discussion including Lyra’s partner Sara Canning, her The financial consequences of the media crisis and friend and colleague Kathryn Johnston and ICTU the financial measures needed to secure the long- Assistant General Secretary Owen Reidy. term future of the NUJ as an independent, cross- Throughout the week there will also be training border union for journalists will dominate the opening events. While conference is confined to delegates and day of conference while the report of General nominated observers, the week-long programme of Secretary Michelle Stanistreet will focus on events is open to all members. -

Complaint by Mrs Nichola Corner on Behalf of the Ms Lyra Mckee

v Issue 412 12 October 2020 Complaint by Mrs Nichola Corner1 on behalf of the Ms Lyra McKee (deceased) about Newsnight: The ‘Real’ Derry Girls and the Dissidents Type of case Fairness and Privacy Outcome Upheld Service BBC 2 Date & time 05 November 2019, 22:45 Category Privacy Summary Ofcom has upheld this complaint about unwarranted infringement of privacy in the programme as broadcast. Case summary The programme featured a report about terrorism in Northern Ireland, with a particular focus on Derry, or Londonderry. The report described the circumstances which led to the murder of Ms Lyra McKee, who was a journalist covering a story when she was hit by a bullet after a gunman opened fire on the police. The programme included a brief piece of footage that appeared to show Ms McKee lying in the street in her dying moments after being shot. The footage, filmed on a mobile phone, included around three seconds which focused on Ms McKee as she lay on the ground with people crowding around her. Whilst the footage was brief, of low quality and Ms McKee was largely obscured, it included a glimpse of her footwear. Mrs Corner, Ms McKee’s sister, complained that Ms McKee’s privacy was unwarrantably infringed in the programme as broadcast by the inclusion of this footage. Ofcom found that Ms McKee had a legitimate expectation of privacy in relation to the broadcast of the footage of her and that this outweighed the broadcaster’s right to freedom of expression and the audience’s right to receive information and ideas without interference, and the public interest in 1 Section 111(2) of the Broadcasting Act 1996 provides that “where the person affected is an individual who has died, a fairness complaint may be made by his personal representative or by a member of the family of the person affected, or by some other person or body closely connected with him (whether as his employer, or as a body of which he was at his death a member, or in any other way)”. -

Collaboration, Collaborators, and Conflict: Archaeology and Peacebuilding in Northern Ireland

Collaboration, Collaborators, and Conflict: Archaeology and Peacebuilding in Northern Ireland Horning, A. (2019). Collaboration, Collaborators, and Conflict: Archaeology and Peacebuilding in Northern Ireland. Archaeologies, 15, 444-465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-019-09378-3 Published in: Archaeologies Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches -

The Peace Journalist

IN THIS ISSUE • PJ project in Northern Ireland • Dispatches from South Korea, Cameroon, Uganda, Ghana • Jake Lynch: 20 years of peacebuilding media At Park University, discussing Peace Journalism with Prof. Raj Gandhi A publication of the Center for Global Peace Journalism at Park University Vol 8 No. 2 - October 2019 October 2019 October 2019 Contents 3 Gandhi at Park U. 14 U.S. Was Gandhi a peace journalist? Filmmaker meets “The Enemy” Cover photos-- Left and top right by Phyllis Gabauer Park Univ. 16 Worldwide peace stud- The Peace Journalist is a semi- Lynch: 20 yrs of peace media ies student annual publication of the Center Alyssa Williams for Global Peace Journalism at Park 18 South Korea discusses the University in Parkville, Missouri. The Journalists gather to discuss PJ elements of Peace Journalist is dedicated to dis- peace with Prof. seminating news and information 19 Ghana Raj Gandhi. for teachers, students, and Radio as a change agent practitioners of PJ. 6 Gandhi, Hate speech 20 Kashmir Submissions are welcome from all. Gandhian principles combat hate We are seeking shorter submissions Outlet gives voice to youth (300-500 words) detailing peace S. Sudan-Uganda journalism projects, classes, propos- 8 21 Cameroon als, etc. We also welcome longer Network connects communities PJ prize;Community media Prof. Gandhi enlightens Park University submissions (800-1200 words) By Steven Youngblood of our opponents.” Indian Opinion journal, Gandhi said, “I about peace or conflict sensitive 10 Northern Ireland 22 South Sudan When asked to describe Mahatma cannot recall a word in those articles journalism projects or programs, as Project energizes journalists Govmt.