Mapping Amundsen's and Scott's Routes Through the Transantarctic Mountains Fifty Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY of the SCOTT GLACIER and WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA

This dissertation has been /»OOAOO m icrofilm ed exactly as received MINSHEW, Jr., Velon Haywood, 1939- GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1967 Geology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTT GLACIER AND WISCONSIN RANGE AREAS, CENTRAL TRANSANTARCTIC MOUNTAINS, ANTARCTICA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Velon Haywood Minshew, Jr. B.S., M.S, The Ohio State University 1967 Approved by -Adviser Department of Geology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report covers two field seasons in the central Trans- antarctic Mountains, During this time, the Mt, Weaver field party consisted of: George Doumani, leader and paleontologist; Larry Lackey, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant. The Wisconsin Range party was composed of: Gunter Faure, leader and geochronologist; John Mercer, glacial geologist; John Murtaugh, igneous petrclogist; James Teller, field assistant; Courtney Skinner, field assistant; Harry Gair, visiting strati- grapher. The author served as a stratigrapher with both expedi tions . Various members of the staff of the Department of Geology, The Ohio State University, as well as some specialists from the outside were consulted in the laboratory studies for the pre paration of this report. Dr. George E. Moore supervised the petrographic work and critically reviewed the manuscript. Dr. J. M. Schopf examined the coal and plant fossils, and provided information concerning their age and environmental significance. Drs. Richard P. Goldthwait and Colin B. B. Bull spent time with the author discussing the late Paleozoic glacial deposits, and reviewed portions of the manuscript. -

2. Disc Resources

An early map of the world Resource D1 A map of the world drawn in 1570 shows ‘Terra Australis Nondum Cognita’ (the unknown south land). National Library of Australia Expeditions to Antarctica 1770 –1830 and 1910 –1913 Resource D2 Voyages to Antarctica 1770–1830 1772–75 1819–20 1820–21 Cook (Britain) Bransfield (Britain) Palmer (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ Resolution and Adventure Williams Hero 1819 1819–21 1820–21 Smith (Britain) ▼ Bellingshausen (Russia) Davis (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ Williams Vostok and Mirnyi Cecilia 1822–24 Weddell (Britain) ▼ Jane and Beaufoy 1830–32 Biscoe (Britain) ★ ▼ Tula and Lively South Pole expeditions 1910–13 1910–12 1910–13 Amundsen (Norway) Scott (Britain) sledge ▼ ▼ ship ▼ Source: Both maps American Geographical Society Source: Major voyages to Antarctica during the 19th century Resource D3 Voyage leader Date Nationality Ships Most southerly Achievements latitude reached Bellingshausen 1819–21 Russian Vostok and Mirnyi 69˚53’S Circumnavigated Antarctica. Discovered Peter Iøy and Alexander Island. Charted the coast round South Georgia, the South Shetland Islands and the South Sandwich Islands. Made the earliest sighting of the Antarctic continent. Dumont d’Urville 1837–40 French Astrolabe and Zeelée 66°S Discovered Terre Adélie in 1840. The expedition made extensive natural history collections. Wilkes 1838–42 United States Vincennes and Followed the edge of the East Antarctic pack ice for 2400 km, 6 other vessels confirming the existence of the Antarctic continent. Ross 1839–43 British Erebus and Terror 78°17’S Discovered the Transantarctic Mountains, Ross Ice Shelf, Ross Island and the volcanoes Erebus and Terror. The expedition made comprehensive magnetic measurements and natural history collections. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

A Satellite Case Study of a Katabatic Surge Along the Transantarctic Mountains D

This article was downloaded by: [Ohio State University Libraries] On: 07 March 2012, At: 15:04 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK International Journal of Remote Sensing Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tres20 A satellite case study of a katabatic surge along the Transantarctic Mountains D. H. BROMWICH a a Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State Universit, Columbus, Ohio, 43210, U.S.A Available online: 17 Apr 2007 To cite this article: D. H. BROMWICH (1992): A satellite case study of a katabatic surge along the Transantarctic Mountains, International Journal of Remote Sensing, 13:1, 55-66 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01431169208904025 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

S. Antarctic Projects Officer Bullet

S. ANTARCTIC PROJECTS OFFICER BULLET VOLUME III NUMBER 8 APRIL 1962 Instructions given by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty ti James Clark Ross, Esquire, Captain of HMS EREBUS, 14 September 1839, in J. C. Ross, A Voya ge of Dis- covery_and Research in the Southern and Antarctic Regions, . I, pp. xxiv-xxv: In the following summer, your provisions having been completed and your crews refreshed, you will proceed direct to the southward, in order to determine the position of the magnet- ic pole, and oven to attain to it if pssble, which it is hoped will be one of the remarka- ble and creditable results of this expedition. In the execution, however, of this arduous part of the service entrusted to your enter- prise and to your resources, you are to use your best endoavours to withdraw from the high latitudes in time to prevent the ships being besot with the ice Volume III, No. 8 April 1962 CONTENTS South Magnetic Pole 1 University of Miohigan Glaoiologioal Work on the Ross Ice Shelf, 1961-62 9 by Charles W. M. Swithinbank 2 Little America - Byrd Traverse, by Major Wilbur E. Martin, USA 6 Air Development Squadron SIX, Navy Unit Commendation 16 Geological Reoonnaissanoe of the Ellsworth Mountains, by Paul G. Schmidt 17 Hydrographio Offices Shipboard Marine Geophysical Program, by Alan Ballard and James Q. Tierney 21 Sentinel flange Mapped 23 Antarctic Chronology, 1961-62 24 The Bulletin is pleased to present four firsthand accounts of activities in the Antarctic during the recent season. The Illustration accompanying Major Martins log is an official U.S. -

Novitatesamerican MUSEUM PUBLISHED by the AMERICAN MUSEUM of NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST at 79TH STREET NEW YORK, N.Y

NovitatesAMERICAN MUSEUM PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 U.S.A. NUMBER 2552 OCTOBER 15, 1974 EDWIN H. COLBERT AND JOHN W COSGRIFF Labyrinthodont Amphibians from Antarctica Labyrinthodont Amphibians from Antarctica EDWIN H. COLBERT Curator Emeritus, The Amer'wan Museum of Natural History Professor Emeritus, Columbia University Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology The Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff JOHN W COSGRIFF Associate Professor of Biology Wayne State University, Michigan AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NUMBER 2552, pp. 1-30, figs. 1-20, table 1 ISSN 0003-0082 Issued October 15, 1974 Price $1.95 Copyright © The American Museum of Natural History 1974 ABSTRACT ian which, following further comparative studies, Labyrinthodont amphibians from the Lower is identified in the present paper as a brachyopid. Triassic Fremouw Formation of Antarctica are The discovery of this specimen-an accidental described. These consist of a fragment of a lower event tangential to Barrett's study of the geology jaw collected at Graphite Peak in the Transant- of the Transantarctic Mountains in the general arctic Mountains in December, 1967, and various region of the Beardmore Glacier-was the stimu- fossils from Coalsack Bluff (west of the lus for a program of vertebrate paleontological Beardmore Glacier and some 140 km., or about collecting in Antarctica. An expedition under the 88 miles, northwest of Graphite Peak) during the auspices of the Institute of Polar Studies of The austral summer of 1969-1970 and from near the Ohio State University and the National Science junction of the McGregor and Shackleton Gla- Foundation went to the Beardmore Glacier area ciers (about 100 km., or 60 miles, more or less, during the austral summer of 1969-1970 for the to the east and a little south of Graphite Peak) during the austral summer of 1970-1971. -

Project ICEFLOW

ICEFLOW: short-term movements in the Cryosphere Bas Altena Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo. now at: Institute for Marine and Atmospheric research, Utrecht University. Bas Altena, project Iceflow geometric properties from optical remote sensing Bas Altena, project Iceflow Sentinel-2 Fast flow through icefall [published] Ensemble matching of repeat satellite images applied to measure fast-changing ice flow, verified with mountain climber trajectories on Khumbu icefall, Mount Everest. Journal of Glaciology. [outreach] see also ESA Sentinel Online: Copernicus Sentinel-2 monitors glacier icefall, helping climbers ascend Mount Everest Bas Altena, project Iceflow Sentinel-2 Fast flow through icefall 0 1 2 km glacier surface speed [meter/day] Khumbu Glacier 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 Mt. Everest 300 1800 1200 600 0 2/4 right 0 5/4 4/4 left 4/4 2/4 R 3/4 L -300 terrain slope [deg] Nuptse surface velocity contours Western Chm interval per 1/4 [meter/day] 10◦ 20◦ 30◦ 40◦ [outreach] see also Adventure Mountain: Mount Everest: The way the Khumbu Icefall flows Bas Altena, project Iceflow Sentinel-2 Fast flow through icefall ∆H Ut=2000 U t=2020 H internal velocity profile icefall α 2A @H 3 U = − 3+2 H tan αρgH @x MSc thesis research at Wageningen University Bas Altena, project Iceflow Quantifying precision in velocity products 557 200 557 600 7 666 200 NCC 7 666 000 score 1 7 665 800 Θ 0.5 0 7 665 600 557 460 557 480 557 500 557 520 7 665 800 search space zoom in template/chip correlation surface 7 666 200 7 666 200 7 666 000 7 666 000 7 665 800 7 665 800 7 665 600 7 665 600 557 200 557 600 557 200 557 600 [submitted] Dispersion estimation of remotely sensed glacier displacements for better error propagation. -

List of Place-Names in Antarctica Introduced by Poland in 1978-1990

POLISH POLAR RESEARCH 13 3-4 273-302 1992 List of place-names in Antarctica introduced by Poland in 1978-1990 The place-names listed here in alphabetical order, have been introduced to the areas of King George Island and parts of Nelson Island (West Antarctica), and the surroundings of A. B. Dobrowolski Station at Bunger Hills (East Antarctica) as the result of Polish activities in these regions during the period of 1977-1990. The place-names connected with the activities of the Polish H. Arctowski Station have been* published by Birkenmajer (1980, 1984) and Tokarski (1981). Some of them were used on the Polish maps: 1:50,000 Admiralty Bay and 1:5,000 Lions Rump. The sheet reference is to the maps 1:200,000 scale, British Antarctic Territory, South Shetland Islands, published in 1968: King George Island (sheet W 62 58) and Bridgeman Island (Sheet W 62 56). The place-names connected with the activities of the Polish A. B. Dobrowolski Station have been published by Battke (1985) and used on the map 1:5,000 Antarctic Territory — Bunger Oasis. Agat Point. 6211'30" S, 58'26" W (King George Island) Small basaltic promontory with numerous agates (hence the name), immediately north of Staszek Cove. Admiralty Bay. Sheet W 62 58. Polish name: Przylądek Agat (Birkenmajer, 1980) Ambona. 62"09'30" S, 58°29' W (King George Island) Small rock ledge, 85 m a. s. 1. {ambona, Pol. = pulpit), above Arctowski Station, Admiralty Bay, Sheet W 62 58 (Birkenmajer, 1980). Andrzej Ridge. 62"02' S, 58° 13' W (King George Island) Ridge in Rose Peak massif, Arctowski Mountains. -

South Pole All the Way Trip Notes

SOUTH POLE ALL THE WAY 2021/22 EXPEDITION TRIP NOTES SOUTH POLE ALL THE WAY EXPEDITION NOTES 2021/22 EXPEDITION DETAILS Hercules Inlet: Dates: November 5, 2021 to January 4, 2022 Duration: 61 days Price: US$72,875 Messner Start: Dates: November 5 to December 30, 2021 Duration: 56 days Price: US$69,350 Axel Heiberg: Dates: November 21 to December 30, 2021 Duration: 40 days Price: US$90,750 An epic journey to the South Pole. Photo: Andy Cole Antarctica has held the imagination of the entire world for over two centuries, yet the allure of this remote continent has not diminished. With huge advances in modern-day technology, travel to any part of the world seems to be considered a ‘fait accomplis’. Yet Antarctica still holds a sense of being impenetrable, a place where man has not tamed nature. Antarctica is a place of adventure. A frontier where we are far removed from our normal ‘safety net’ ROUTE OPTIONS and where we need to rely on our own resources HERCULES INLET (61 DAYS) and decision making to survive. It is in these environments that we are truly in touch with The route from Hercules Inlet is the ultimate nature, where we can embark on a journey of challenge; a journey that traverses 1,130km/702 discovery to remote and untouched places. miles from the edge of the Ronne Ice Shelf to the Geographic South Pole. It is an expedition that In the Southern Hemisphere summer, when the will allow you to join an elite group who have sun is in the sky 24 hours each day, Adventure undertaken this adventure under their own power. -

P1616 Text-Only PDF File

A Geologic Guide to Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes By Gary R. Winkler1 With contributions by Edward M. MacKevett, Jr.,2 George Plafker,3 Donald H. Richter,4 Danny S. Rosenkrans,5 and Henry R. Schmoll1 Introduction region—his explorations of Malaspina Glacier and Mt. St. Elias—characterized the vast mountains and glaciers whose realms he invaded with a sense of astonishment. His descrip Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve (fig. tions are filled with superlatives. In the ensuing 100+ years, 6), the largest unit in the U.S. National Park System, earth scientists have learned much more about the geologic encompasses nearly 13.2 million acres of geological won evolution of the parklands, but the possibility of astonishment derments. Furthermore, its geologic makeup is shared with still is with us as we unravel the results of continuing tectonic contiguous Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, Kluane processes along the south-central Alaska continental margin. National Park and Game Sanctuary in the Yukon Territory, the Russell’s superlatives are justified: Wrangell–Saint Elias Alsek-Tatshenshini Provincial Park in British Columbia, the is, indeed, an awesome collage of geologic terranes. Most Cordova district of Chugach National Forest and the Yakutat wonderful has been the continuing discovery that the disparate district of Tongass National Forest, and Glacier Bay National terranes are, like us, invaders of a sort with unique trajectories Park and Preserve at the north end of Alaska’s panhan and timelines marking their northward journeys to arrive in dle—shared landscapes of awesome dimensions and classic today’s parklands. -

The Antarctic Sun, December 28, 2003

Published during the austral summer at McMurdo Station, Antarctica, for the United States Antarctic Program December 28, 2003 Photo by Kristan Hutchison / The Antarctic Sun A helicopter lands behind the kitchen and communications tents at Beardmore Camp in mid-December. Back to Beardmore: By Kristan Hutchison Researchers explore the past from temporary camp Sun staff ike the mythical town of Brigadoon, a village of tents appears on a glacial arm 50 miles L from Beardmore Glacier about once a decade, then disappears. It, too, is a place lost in time. For most people, a visit to Beardmore Camp is a trip back in history, whether to the original camp structure from 19 years ago, now buried under snow, or to the sites of ancient forests and bones, now buried under rock. Ever since Robert Scott collected fos- sils on his way back down the Beardmore Glacier in February 1912, geologists and paleontologists have had an interest in the rocky outcrops lining the broad river of ice. This year’s Beardmore Camp was the third at the location on the Lennox-King Glacier and the researchers left, saying there Photo by Andy Sajor / Special to The Antarctic Sun Researchers cut dinosaur bones out of the exposed stone on Mt. Kirkpatrick in December. See Camp on page 7 Some of the bones are expected to be from a previously unknown type. INSIDE Quote of the Week Dinosaur hunters Fishing for fossils “The penguins are happier than Page 9 Page 11 Trackers clams.” Plant gatherers - Adelie penguin researcher summing Page 10 Page 12 up the attitude of a colony www.polar.org/antsun 2 • The Antarctic Sun December 28, 2003 Ross Island Chronicles By Chico That’s the way it is with time son. -

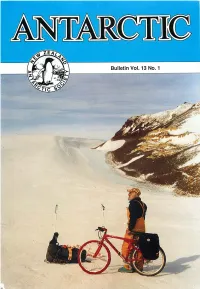

Bulletin Vol. 13 No. 1 ANTARCTIC PENINSULA O 1 0 0 K M Q I Q O M L S

ANttlcnc Bulletin Vol. 13 No. 1 ANTARCTIC PENINSULA O 1 0 0 k m Q I Q O m l s 1 Comandante fettai brazil 2 Henry Arctowski poono 3 Teniente Jubany Argentina 4 Artigas Uruguay 5 Teniente Rodolfo Marsh chile Bellingshausen ussr Great Wall china 6 Capitan Arturo Prat chile 7 General Bernardo O'Higgins chile 8 Esperania argentine 9 Vice Comodoro Marambio Argentina 10 Palmer us* 11 Faraday uk SOUTH 12 Rotheraux 13 Teniente Carvajal chile SHETLAND 14 General San Martin Argentina ISLANDS jOOkm NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY MAP COPYRIGHT Vol.l3.No.l March 1993 Antarctic Antarctic (successor to the "Antarctic News Bulletin") Vol. 13 No. 1 Issue No. 145 ^H2£^v March.. 1993. .ooo Contents Polar New Zealand 2 Australia 9 ANTARCTIC is published Chile 15 quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Italy 16 Society Inc., 1979 United Kingdom 20 United States 20 ISSN 0003-5327 Sub-antarctic Editor: Robin Ormerod Please address all editorial inquiries, Heard and McDonald 11 contributions etc to the Macquarie and Campbell 22 Editor, P.O. Box 2110, Wellington, New Zealand General Telephone: (04) 4791.226 CCAMLR 23 International: +64 + 4+ 4791.226 Fax: (04) 4791.185 Whale sanctuary 26 International: +64 + 4 + 4791.185 Greenpeace 28 First footings at Pole 30 All administrative inquiries should go to Feinnes and Stroud, Kagge the Secretary, P.O. Box 2110, Wellington and the Women's team New Zealand. Ice biking 35 Inquiries regarding back issues should go Vaughan expedition 36 to P.O. Box 404, Christchurch, New Zealand. Cover: Ice biking: Trevor Chinn contem plates biking the glacier slope to the Polar (S) No part of this publication may be Plateau, Mt.