Collective Action and the Deployment of Teachers in Niger a Political Economy Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Localization of the Global Agendas How Local Action Is Transforming Territories and Communities

2019 The Localization of the Global Agendas How local action is transforming territories and communities Fifth Global Report on Decentralization and Local Democracy 2 GOLD V REPORT GOLD V REPORT —— XXXXXX 3 © 2019 UCLG The right of UCLG to be identified as author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. United Cities and Local Governments Cités et Gouvernements Locaux Unis Ciudades y Gobiernos Locales Unidos Avinyó 15 08002 Barcelona www.uclg.org DISCLAIMERS The terms used concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development do not necessarily reflect the opinion of United Cities and Local Governments. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of this report do not necessarily reflect the views of all the members of United Cities and Local Governments. This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of UCLG and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union. This document has been financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. -

Technical Appendix

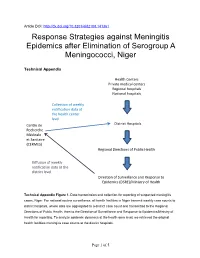

Article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2108.141361 Response Strategies against Meningitis Epidemics after Elimination of Serogroup A Meningococci, Niger Technical Appendix Health Centers Private medical centers Regional hospitals National hospitals Collection of weekly notification data at the health center level Centre de District Hospitals Recherche Médicale et Sanitaire (CERMES) Regional Directions of Public Health Diffusion of weekly notification data at the district level Direction of Surveillance and Response to Epidemics (DSRE)/Ministry of Health Technical Appendix Figure 1. Data transmission and collection for reporting of suspected meningitis cases, Niger. For national routine surveillance, all health facilities in Niger transmit weekly case counts to district hospitals, where data are aggregated to a district case count and transmitted to the Regional Directions of Public Health, then to the Direction of Surveillance and Response to Epidemics/Ministry of Health for reporting. To analyze epidemic dynamics at the health area level, we retrieved the original health facilities meningitis case counts at the district hospitals. Page 1 of 5 Evaluation of Completeness of the Health Center Database The country has 8 regions (Tahoua, Tillabery, Agadez, Diffa, Maradi, Niamey, Zinder, and Dosso), 42 districts, and 732 health areas containing >1,500 health centers. To assess the completeness of this database, we compared the resulting district-level weekly case counts with those included in the national routine surveillance reports. A -

Dynamique Des Conflits Et Médias Au Niger Et À Tahoua Revue De La Littérature

Dynamique des Conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua Revue de la littérature Décembre 2013 Charline Burton Rebecca Justus Contacts: Charline Burton Moutari Aboubacar Spécialiste Conception, Suivi et Coordonnateur National des Evaluation – Afrique de l’Ouest Programmes - Niger Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire [email protected] + 227 9649 00 39 [email protected] +225 44 47 24 57 +227 90 60 54 96 Dynamique des conflits et Médias au Niger et à Tahoua | PAGE 2 Table des matières 1. Résumé exécutif ...................................................................................................... 4 Contexte ................................................................................................. 4 Objectifs et méthodologie ........................................................................ 4 Résultats principaux ............................................................................... 4 2. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Contexte de la revue de littérature ............................................................... 7 2.2 Méthodologie et questions de recherche ....................................................... 7 3. Contexte général du Niger .................................................................................. 10 3.1 Démographie ............................................................................................. 10 3.2 Situation géographique et géostratégique ............................................ -

Electrical Sector and Renewable Energies SOFTWARE & IT

SOFTWARE & IT SOLUTIONS Electrical Sector and Renewable Energies Copyright © 2008-2019 IED S.A.S, All Rights Reserved. WHO ARE WE? As an independent consulting and engineering firm, IED has been involved in the provision of sustai- nable and strategic energy services since its creation in 1988 . From power systems planning to feasibil- ity studies and operational management, IED offers a wide range of IT solutions to support your needs in the field of electrification, network planning and renewable energy project development. Specialized tools for institutions, companies, local authorities and consulting firms involved in the energy sector. GIS AT THE SERVICE OF PLANNING ACCESS TO ENERGY Geographic information systems (GIS) have the capacity to store and use alphanumeric data as well as geographic data offering new opportunities for the decentralized rural planning sector, energy production and demand assess- ment. IED combines its knowledge of the energy sector with its solid expertise in the design of information systems, the development of alphanumeric and cartographic databases and spatial analysis through several GIS software (ArcGis, Manifold, QGIS...). The data collection (alphanumeric and cartographic) and its consolidation (geographic, topographical, demographic, socio-economic data, etc.) is one of the main capabilities and qualities of IED experts who are used to operating in contexts where data access is often difficult. Overlay of multisectoral data Visualization of different layers of data to take into account a large number of factors influencing the final deci- sion: socio-economic infrastructure, road networks, rivers, protected areas, ...) Publication of decision support maps Production of detailed decision-making maps for decision-makers (wind farm identification, energy constraints, social and environmental impact ...) Dissemination, communication and consensus of data Communication on geographical data, in electronic, paper or on the Internet. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Arrêt N° 01/10/CCT/ME Du 23 Novembre 2010

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du vingt trois novembre deux mil dix tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-031 du 27 mai 2010 portant code électoral et ses textes modificatifs subséquents ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2010-668/PCSRD du 1er octobre 2010 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le référendum sur la Constitution de la VIIème République ; Vu la requête en date du 8 novembre 2010 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) et les pièces jointes ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 003/PCCT du 8 novembre 2010 de Madame le Président du Conseil Constitutionnel portant désignation d’un Conseiller-Rapporteur ; Ensemble les pièces jointes ; Après audition du Conseiller – rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME Considérant que par lettre n° 190/P/CENI en date du 8 novembre 2010, le Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante (CENI) a saisi le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition aux fins de valider -

Rapport De Mission Corrige

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER ………………… MINISTERE DES MINES ET DE L’ENERGIE Improving Economic and Social Impact of Rural Electrification (IMPROVES-RE) Amélioration de l’impact social et économique de l’électrification rurale BURKINA FASO, CAMEROUN, MALI et NIGER RAPPORT DE MISSION Du 11 Mars 2006 au 05 Avril 2006 ENQUETES SOCIOECONOMIQUES APPROFONDIES DANS LA ZONE PILOTE DEPARTEMENTS DE KEITA ET ABALAK Coordination européenne Innovation Energie Développement (IED) 2, chemin de la chauderaie 69340 Francheville – France Tél. +33 4 72 59 13 20, Fax : +33 4 72 59 13 39 [email protected] www.ied-sa.fr Coordination européenne ANNEXES SOMMAIRE I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................................................. 2 II. ORGANISATION DE LA MISSION.............................................................................................................................. 2 2.1. CHOIX DES LOCALITES......................................................................................................................................................2 2.2. FICHES D’ENQUETES.........................................................................................................................................................2 2.3. PREPARATION DE L’EQUIPE.............................................................................................................................................2 III. DEROULEMENT DE LA MISSION........................................................................................................................... -

REGIS-ER Midterm Evaluation

EVALUATION REGIS-ER MIDTERM PERFORMANCE EVALUATION REPORT OCTOBER 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. REGIS-ER MIDTERM PERFORMANCE EVALUATION USAID/SENEGAL Contracted under AID-685-C-15-00003 USAID Senegal Monitoring and Evaluation Project Cover Photo Beneficiary of a Moringa Oasis Garden at Zaboure, Maradi, Niger Photo by the Evaluation Team. DISCLAIMER This evaluation is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the sole responsibility of Management Systems International and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 4 Evaluation Objectives and Questions ............................................................................................................ 4 Project Background ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Evaluation Design, Methods and Limitations ................................................................................................ 4 Findings and Conclusions ................................................................................................................................. -

1 EVALUATION DU 8Ème PROGRAMME DE PAYS UNFPA

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fonds des Nations Unies pour la Population EVALUATION DU 8ème PROGRAMME DE PAYS UNFPA/NIGER 2014-2018 Période évaluée : 1er Janvier 2014 — 30 Juin 2017 RAPPORT FINAL D’EVALUATION Juin 2018 1 Page 1 Equipe d’évaluation Chef de mission, Consultant International, Thématique SSR Tiburce NYIAMA Consultant National, Thématique Population & Harouna HAMIDOU Développement Exception : Le contenu de ce rapport ne reflete pas nécessairement l’opinion de l’UNFPA. Il s’agit de l’appréciation des consultants suite à l’analyse des données et évidences collectées. 2 Page 2 REMERCIEMENTS Des acteurs nationaux et internationaux ont contribué à l’évaluation finale du 8ème Programme de coopération entre l’UNFPA et l’Etat du Niger. L’équipe d’évaluation reconnaît au Bureau Pays de l’UNFPA au Niger et aux membres du Groupe de Référence de l’Evaluation l’accompagnement continu apporté. Une appréciation particulière va à l’endroit de M. le Représentant Résident, Dr. Nestor Azandegbe, de l’Assistant Représentant Résident et Coordinateur du Programme, M. Hassane Ali et du Chargé de Programme Suivi et Evaluation, M. Abdoul Razaou Issa pour la qualité de leur investissement en vue du succès de l’évaluation. M. Simon-Pierre Tegang, Conseiller Technique en Suivi et Evaluation au bureau Régional de l’UNFPA pour l’Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre à Dakar/Sénégal, a apporté l’assistance technique nécessaire. L’obligeance de l’équipe d’évaluation va aussi à l’endroit des 7 Ministères en charge de la Santé, de la Jeunesse, du Genre, de la population, de l’enseignement secondaire, de la formation professionnelle et technique et du Plan, l’ENESP D. -

Migration and Markets in Agadez Economic Alternatives to the Migration Industry

Migration and Markets in Agadez Economic alternatives to the migration industry Anette Hoffmann CRU Report Jos Meester Hamidou Manou Nabara Supported by: Migration and Markets in Agadez: Economic alternatives to the migration industry Anette Hoffmann Jos Meester Hamidou Manou Nabara CRU Report October 2017 Migration and Markets in Agadez: Economic alternatives to the migration industry October 2017 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Men sitting on their motorcycles by the Agadez market. © Boris Kester / traveladventures.org Unauthorised use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Anette Hoffmann is a senior research fellow at the Clingendael Institute’s Conflict Research Unit. -

Niger 2020 Human Rights Report

NIGER 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Niger is a multiparty republic. In the first round of the presidential elections on December 27, Mohamed Bazoum of the ruling coalition finished first with 39.3 percent of the vote. Opposition candidate Mahamane Ousman finished second with 16.9 percent. A second round between the two candidates was scheduled for February 21, 2021. President Mahamadou Issoufou, who won a second term in 2016, was expected to continue in office until the second round was concluded and the winner sworn into office. International and domestic observers found the first round of the presidential election to be peaceful, free, and fair. In parallel legislative elections also conducted on December 27, the ruling coalition preliminarily won 80 of 171 seats, and various opposition parties divided the rest, with several contests still to be decided. International and local observers found the legislative elections to be equally peaceful, free, and fair. The National Police, under the Ministry of Interior, Public Security, Decentralization, and Customary and Religious Affairs (Ministry of Interior), is responsible for urban law enforcement. The Gendarmerie, under the Ministry of National Defense, has primary responsibility for rural security. The National Guard, also under the Ministry of Interior, is responsible for domestic security and the protection of high-level officials and government buildings. The armed forces, under the Ministry of National Defense, are responsible for external security and, in some parts of the country, for internal security. Every 90 days the parliament reviews the state of emergency declaration in effect in the Diffa Region and in parts of Tahoua and Tillabery Regions. -

World Bank Document

Documentof The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 17260 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF NIGER PUBLIC WORKS AND EMPLOYMENT PROJECT CREDIT 2209-NIR December 23, 1997 Public Disclosure Authorized Water and Urban Sector Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performanceof their official duties. Its contents may not otherwisebe disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Currencyunit = CFA Franc(CFAF) 1990: US dollar = 285 CFAF 1991: US dollar = 283 CFAF 1992: US dollar = 265 CFAF 1993: US dollar = 280 CFAF 1994: US dollar = 555 CFAF 1995: US dollar = 520 CFAF 1996: US dollar = 520 CFAF 1997: US dollar = 540 CFAF WEIGHTSAND MEASURES Metric System FISCALYEAR January I - December 31 ACRONYMSAND ABBREVIATIONS AFN Women'sAssociation of Niger AGETIP Agenced'Execution des Travauxd'Interet PublicContre le Sous-Emploi [PublicWorks and EmploymentAgency] AVCN Associationof Cities and Communes[i.e. Municipalities]of Niger. CFD CaisseFran9aise de Developpement CIDA Canada InternationalDevelopment Agency CNMP CommissionNationale des MarchesPublics [National Public Procurement Commission] EDF EuropeanDevelopment Fund EElC EuropeanEconomic Community FSD Fonds Socialde Developpement(France) IDA InternationalDevelopment Association 1(1W Kreditanstaltfbir Wiederaufbau (Germany) N][GETIP AgenceNigerienne de Travauxd'Interet Publicpour l'Emploi [Niger's PublicWorks and EmploymentAgency] O]PEC Organizationof PetroleumExporting Countries PACSA Programto Alleviatethe Social Costsof Adjustment(Niger) PPF ProjectPreparation Fund SAR StaffAppraisal Report SPEIN Businessand IndustryEmployers' Association of Niger SYNAPEMEN NationalAssociation of Smalland Medium-SizedEnterprises of Niger TAIMAKO Mutual GuaranteeCompany TIPE Travauxd'Inter6t Publicpour l'Emploi [Employment-creat'igPublic Works] UNC NationalUnion of Cooperatives USTN Federationof Labor Unionsof Niger Vice-President : Mr.