Towards a Muslim Poetics of Nature*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Monuments Fund and Partners Convene Watch Day Event at the Takkiyat Ibrahim Al-Gulshani in Cairo

For Immediate Release World Monuments Fund and partners convene Watch Day event at the Takkiyat Ibrahim al-Gulshani in Cairo Takkiyat Ibrahim al-Gulshani is a major Sufi monument in Historic Cairo that is subject to a conservation project by the World Monuments Fund Event convened by World Monuments Fund, Ministry of Antiquities, Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation, Art Jameel, and Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport Alumni from the Jameel House of Traditional Arts in Cairo participated in the Watch Day Cairo, Egypt | July 3, 2019 -On June 29, the World Monuments Fund (WMF) convened a Watch Day event at the Takkiyat Ibrahim al-Gulshani, an important Sufi monument in the heart of Historic Cairo. The event was held with support from the Ministry of Antiquities and the Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation, and in participation with Art Jameel, an organisation that supports heritage, education and the arts, the Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport, and Turath Conservation Group (TCG). The Takkiyat Ibrahim al-Gulshani was the first religious foundation established in Cairo after the Ottoman conquest of 1517 and was built between 1519 and 1524 by the eponymous Sufi sheikh from modern Azerbaijan. The complex was designed around a freestanding Mamluk-style mausoleum in the middle of a courtyard, framed by Sufi cells, mosque, kitchen, shops, and apartments for his devoted followers and family members. Until recently, the Takkiyat Ibrahim al-Gulshani was abandoned and lay in a state of disrepair, a victim of neglect, looting and the 1992 Cairo earthquake. Listed as a World Monuments Watch site in 2018, emphasising the urgent need for rehabilitation, the Takkiyat Ibrahim al-Gulshani is the subject of a major ongoing conservation effort by the WMF, supported by the Ministry of Antiquities and the Ambassadors Fund. -

Persian Manuscripts

A HAND LIST OF PERSIAN MANUSCRIPTS By Sahibzadah Muhammad Abdul Moid Khan Director Rajasthan Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute, Tonk RAJASTHAN MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD ARABIC PERSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE RAJASTHAN, TONK 2012 2 RAJASTHAN MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD ARABIC PERSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE RAJASTHAN, TONK All Rights Reserved First Edition, 2012 Price Rs. Published by RAJASTHAN MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD ARABIC PERSIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE RAJASTHAN, TONK 304 001 Printed by Navjeevan Printers and Stationers on behalf of Director, MAAPRI, Tonk 3 PREFEACE Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic Persian Research Institute, Rajasthan, Tonk is quenching the thirst of the researchers throughout the world like an oasis in the desert of Rajasthan.The beautiful building of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Arabic and Persian Research Institute Rajasthan, Tonk is situated in the valley of two historical hills of Rasiya and Annapoorna. The Institute is installed with district head quarters at Tonk state Rajasthan in India. The Institute is 100 kms. away at the southern side from the state capital Jaipur. The climate of the area is almost dry. Only bus service is available to approach to Tonk from Jaipur. The area of the Institute‟s premises is 1,26,000 Sq.Ft., main building 7,173 Sq.Ft., and Scholar‟s Guest House is 6,315 Sq.Ft. There are 8 well furnished rooms carrying kitchen, dining hall and visiting hall, available in the Scholar‟s Guest House. This Institute was established by the Government of Rajasthan, which has earned international repute -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Birinci Uluslararası Suna & İnan Kıraç Akdeniz Uygarlıkları Sempozyumu

Birinci Uluslararası Suna & İnan Kıraç Akdeniz Uygarlıkları Sempozyumu 26-29 MART 2019 | AN TALYA BİLDİRİLER Editörler Oğuz Tekin Christopher H. Roosevelt Engin Akyürek Tarih Boyunca Anadolu’da Hayırseverlik Birinci Uluslararası Suna & İnan Kıraç Akdeniz Medeniyetleri Sempozyumu 26-29 Mart, 2019 | Antalya Bildiriler Editörler Oğuz Tekin Christopher H. Roosevelt Engin Akyürek Yardımcı Editörler Remziye Boyraz Seyhan Arif Yacı Bu bildiriler kitabındaki tüm makaleler hakem kontrolünden geçmiştir. Danışma Kurulu Mustafa Adak Angelos Chaniotis Christian Marek Leslie Peirce Amy Singer İngilizceden Türkçeye Çeviri Özgür Pala ISBN 978-605-7685-66-7 Kitap Tasarımı Gökçen Ergüven © 2020 Koç Üniversitesi Sertifika no: 18318 Kapak Tasarımı Tüm hakları saklıdır. Bu kitabın hiçbir bölümü Koç Çağdaş İlke Ünal Üniversitesi ve yazarların yazılı izni olmaksızın çoğaltılamaz ve kopyalanamaz. Bu bildiriler kitabı, Koç Üniversitesi’nin üç araştırma merkezi, AKMED, ANAMED ve GABAM tarafından Vehbi Koç Vakfı’nın İletişim 50. yılı nedeniyle yayımlanmıştır. Kitabın İngilizce versiyonu Koç Üniversitesi Suna & İnan Kıraç Akdeniz “Philanthropy in Anatolia through the Ages. The First International Medeniyetleri Araştırma Merkezi (AKMED) Suna & İnan Kıraç Symposium on Mediterranean Civilizations, March 26-29, 2019 | Antalya Proceedings” basılı olarak yayımlanmış Barbaros Mah. Kocatepe Sok. No: 22 olup Türkçe versiyonu sadece dijital olarak yayımlanmaktadır. Kaleiçi 07100 Antalya, Türkiye TARİH BOYUNCA ANADOLU’DA HAYIRSEVERLİK Birinci Uluslararası Suna & İnan Kıraç -

A Study of the Modern-Day Scholarship and Primary Sources on Ibrāhīm-I Gulshanī and the Khalwatī-Gulshanī Order of Dervishes Side EMRE*

Türkiye Araştırmaları Literatür Dergisi, Cilt 15, Sayı 30, 2017, 107-130 A Study of the Modern-Day Scholarship and Primary Sources on Ibrāhīm-i Gulshanī and The Khalwatī-Gulshanī Order of Dervishes Side EMRE* Historical Background of the Gulshanis1 As an offshoot of the well-known late medieval Khalwatīyya order2 in Iran and Azerbaijan, the followers/disciples of Ibrāhīm-i Gulshanī (d. 940/1534), a * Side Emre is an Associate Professor of Islamic History at Texas A&M University, Department of History, TX USA. 1 The ideas presented in this section were discussed in depth in Side Emre’s Ibrahim-i Gulshani and the Khalwati-Gulshani Order: Power Brokers in Ottoman Egypt (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2017) (hereafter Emre, Power Brokers). 2 Modern-day scholarship examines the status of the Khalwatīyya as a popular order emerging in Azerbaijan and spreading their influence in Anatolia, Arab lands, and the Balkans where their members gained popularity among Turkish-speaking communities establishing one of the common denominators of their cultural, social, and religious heritage. In Anatolia, Shirvani’s ordained successors established various sub-branches in Adrianople, Istanbul or Kastamanonu in approximately two generations following his death. I would like to thank one of my readers for clarifying the speading of the Khalwatī sub-branches in Anatolia. For details see, John J. Curry, The Transformation of Muslim Mystical Thought in the Ottoman Empire: The Rise of the Halveti Order, 1350-1650, Edinbugh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010 (Curry, Transformation); Mustafa Aşkar, “Bir Türk Tarikatı Olarak Halvetiyye’nin Tarihi Gelişimi ve Halvetiyye Silsilesinin Tahlili,” Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyet Fakültesi Dergisi 39 (1999); for the transmission of Khalwatīyya to the Ottoman lands, please see Hasan Karataş, “The Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order: A Political Story Revisited” Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association. -

The Making of an Order: an Ethnography of Romani Sufis in Uskudar

IBN HALDUN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY MASTER THESIS THE MAKING OF AN ORDER: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF ROMANI SUFIS IN USKUDAR HAKTAN TURSUN THESIS SUPERVISOR: ASSOC. PROF. RAMAZAN ARAS ISTANBUL, 2019 IBN HALDUN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY MASTER THESIS THE MAKING OF AN ORDER: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF ROMANI SUFIS IN USKUDAR by HAKTAN TURSUN A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology. THESIS SUPERVISOR: ASSOC. PROF. RAMAZAN ARAS ISTANBUL, 2019 ÖZ BİR TARİKATIN İNŞASI: ÜSKÜDAR’DAKİ ROMAN SUFİLERİN ETNOGRAFYASI Tursun, Haktan Sosyoloji Tezli Yüksek Lisans Programı Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. Ramazan Aras Haziran 2019, 121 Sayfa Bu tez Roman sakinleriyle bilinen Üsküdar Selami Ali Mahallesi’ndeki Gülşeni- Sezai tarikatının oluşum ve dönüşüm sürecinin izini sürmektedir. Tipik bir tasavvufi hareketi oluşturan unsurlar karizmatik bir lider, kutsal bir mekan ve ritüellerle tecessüm eden inançlar sistemi olarak belirlenmiştir. Bu çalışma boyunca bu üç bileşenin Selami Ali bağlamında inşası ve Roman kimliği ile sufi kimliğinin sufi kimliği ile uyumu incelenmektedir. Sonuç olarak yaygın olan önyargısal kanaatin aksine Roman ve sufi kimliklerinin farklılıktan ziyade paralellik arz ettiği ve bunun da mahallede yeni dergahın yerleşmesine katkıda bulunduğu yargısına varılmaktadır. Saha çalışması bir aydan uzun olmayan aralıklarla, 2018-2019 yılları arasında 18 ay boyunca sürmüştür ve bu süre zarfında katılımcı gözlem ve derinlemesine mülakat yöntemleriyle bu çalışmanın ana verileri toplanmıştır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Tasavvuf, Roman Kimliği, Kutsal Alan, Karizma, Ritüel. iv ABSTRACT THE MAKING OF AN ORDER: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF ROMANI SUFIS IN USKUDAR Tursun, Haktan MA in Sociology Thesis Supervisor: Assoc. -

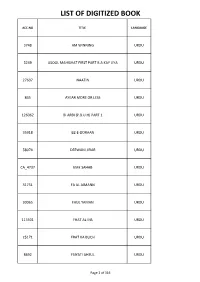

List of Digitized Book

LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK ACC.NO TITLE LANGUAGE 3748 AM WINNING URDU 5249 ASOOL MAHISHAT FIRST PART B.A KAY LIYA URDU 27607 NAATIN URDU 845 AYEAR MORE OR LESS URDU 126062 BI ARBI (P.B.U.H) PART 1 URDU 35918 BZ-E-DORAAN URDU 58074 DEEWANI JIRAR URDU CA_4737 EME SAHAB URDU 31751 FA AL AIMANN URDU 30065 FAUL YAMAN URDU 113501 FHAT AL INS URDU 25171 FRAT KA BUCH URDU 8692 FSIYATI AHSUL URDU Page 1 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 30138 FSIYAT-I-AFFA URDU 34069 FTAHUL YAMAN URDU 1907 FTAHUL YAMAN BATASHYAT URDU 24124 GAMA-I-TIBISHAZAD URDU 58190 GAMAT UL ASRAR URDU 3509 GD SAKHN URDU 64958 GMA SARMAD URDU 114806 GMAH JAVEED URDU 30328 GMAY ZAR URDU 180689 GSH FIRQAADI URDU 126188 HBZ HAYAT URDU 23817 I AUR PURANI TALEEM URDU 38514 IR G KHAYAL URDU 63302 JANGI AZADI ATHARA SO SATAWAN URDU Page 2 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 27796 KASH WA KASH URDU 24338 L DAMNIYATI URDU 57853 LAH TASLEEM URDU 5328 MEYATI KEMEYA KI DARSI KITAB URDU 36585 MOD-E-ZINDAGI URDU 113646 MU GAZAL FARSI URDU 1983 PAD MA SHEIKH FARIDIN ATTAR URDU ASL101 PARISIAN GRAMMER URDU 109279 QASH-I-AKHIR URDU 36043 QOOSH MAANI URDU 7085 QOOSHA RANGA RANG URDU 59166 QSH JAWOODAH URDU 38510 QSH WA NIGAAR URDU 23839 RA ZIKIR HUSSAIN(AS) URDU Page 3 of 316 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 456791 SAB ZELI RIYAZI URDU 5374 SEEBIYAT URDU 55986 SHRIYATI MAJID FIRST PART URDU 56652 SIRUL SHQEEN WA GAZLIYAT WA QASAYID URDU 47249 TAIEJ ALZAHAN WAFIZAN AL FIKAR URDU 11195 TAK KHATHA URDU ASL124 TIYA KALAM URDU 109468 VEEN BHARAT URDU CA_4731 WA-E-SHAIDA URDU ASL_286 YA HISAAB URDU 39350 ZAM HIYA HIYA URDU -

Menakib-I Ibrahim Gulshani”(On the Basis of Scientific-Critical Text)

R u m e l i D E Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi 2 0 2 0 . Ö 8 ( K a s ı m )/ 3 3 7 “Menakıb-ı İbrahim Gülşeni” eserini tekstoloji (metinsel eleştiri) araştırma (inceleme esasında) / H. Veliyeva (337-348. s.) 26-The textological analysis of the “Menakib-i Ibrahim Gulshani”(on the basis of scientific-critical text) Hacer VELİYEVA1 APA: Veliyeva, H. (2020). Textological analysis on the basis of scientific-critical text “Menakib-i Ibrahim Gulshani”. RumeliDE Dil ve Edebiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, (Ö8), 337-348. DOI: 10.29000/rumelide.825935. Abstract The literary and linguistic activity of Muhyi Gulshani, one of the ancient poets and linguists were analyzed. His work called "Menakib-i Ibrahim Gulshani" is one of the examples of ancient art giving some information about the development of literature science in the Middle Ages and compare it with the current state of science as a whole can give us a basis to determine the development of science in the ancient times and its modern level. Without knowing the past it is not easy to step up to future. The basic aim of this study is: 1) to carry out a textological analysis of the work, 2) to make a tour to the creative activity of Ibrahim Gulshani, 3) to study his life through "Menakib", 4) to introduce him to the people of the Azerbaijani where he was brought up, 5) to analyze his artistic examples in the literary-stylistic direction, derived from his poetic ability, 6) to promote the poet’s literary heritage, and figurative-emotional creative talent in the context of entire East. -

Ode Mixing and Style Repertoire in Sufi Folk Literature of Urdu and Punjabi

S ;ODE MIXING AND STYLE REPERTOIRE IN SUFI FOLK LITERATURE OF URDU AND PUNJABI °THESIS ' SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD-OF THE DEGREE OF IN ._ _ _ - ._ . COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIAN LANGUAGES & CULTURE - BY RABIA NASIR UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. A.R. FATIHI CENTRE FOR COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIAN LANGUAGES & CULTURE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH-202002 (INDIA) 2013 'wccsILc CENTRE FOR COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INDIAN LANGUAGES & CULTU Dated .............................. Cerfif i caste This is to certify that the thesis entitled "Code !Mi ing and Style pertoire in Sufi To( , Literature of 4Jrdu and tPunja6i" being submitted by 9rfs. cR¢6ia Nash' for the award of the (Degree of (Doctor of (Philosophy in Comparative Studies of Indian Languages aZ Culture. Entire research work has been carried out under my guidance and supervision and is original 'This thesis embodies the work of the candidate herself and to my knowledge, it contains her own of gina(workanct no part of this thesis was earlier submitted for the award of any degree to any other institute or university. It rs further added that she has completed the course workand has published a research paper in International journal of Advancement in ovf. A.VFatihi '4search eZ Technology ("o( 2, Issue 1, (Director January 2013) IJOJ4R`7 ISS_"V 2278-7763. She Centre for Comparative Study of has also made a pre-submission presentation. Indian Languages and Culture A%11V, math. (Supervisor) DI RECTO Centre for Comparative Sh. r ' of Indian Languages & Cc- B-2, Zakaut ah Roy — AMU. Aligarh-2'Pf' ; Acknowledgements All the praises and thanks are to Allah (The Only God and Lord of all). -

Gulshani Order of Dervishes

Türkiye Araştırmaları Literatür Dergis~ Cilt 15, Sayı30, 2017, 107-130 A Study of the Modern-Day Scholarship and Primary Sources on Ihrahim-i Gulshani and The Khalwati -Gulshani Order of Dervishes SideEMRE* Historical Background of the Gulshanis1 As an offshoot of the well-known Iate medieval Khalwatryya order2 in Iran and Azerbaijan, the followers/disciples of Ihrahim-i Gulshani (d. 940/1534), a Side Eınre is an Associate Professor oflslaınic History at Texas A&M University, Department of History, TX USA. The ide as presented in this seetion were discussed in depthin Side Eınre's Ihrahim-i Gulshanı and the Khalwatı-Gulshanı Order: Power Brokers in Ottoman Egypt (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 201 7) (hereafter Eınre, Power Brokers). 2 Modem -day scholarship exaınines the status of the Klıalwatiyya as a popular order emerging in Azerbaijan and spreading their influence in Anatolia, Arab lands, and the Balkans where their members gained popularity among Turkish-speaking communities establishing one of the common denominators of their cultural, social, and religious heritage. In Anatolia, Shirvani's ordained successors established various sub-branches in Adrianople, Istanbul or Kastamanonu in approximately two generations following his death. I would like to thank one of my readers for clarifying the speading of the Klıalwati sub-branches in Anatolia. For details see, John J. Curry, The Transformatian of Muslim Mystical Thought in the Ottoman Empire: The Rise ofthe Halveti Order, 1350-1650, Edinbugh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010 (Curry, Transformation); Mustafa Aşkar, "Bir Türk Tarikatı Olarak Halvetiyye'nin Tarihi Gelişimi ve Halvetiyye SUsilesinin Tahlili," Ankara Üniversitesi !lahiyet Fakültesi Dergisi 39 (1999); for the transmission of Klıalwatiyya to the Ottoman lands, please see Hasan Kara taş, "The Ottomanization of the Halvetiye Sufi Order: A Political Story Revisited" Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association. -

A Theo-Poetics of the Flesh

Imagining Forth the Incarnation: A Theo-Poetics of the Flesh The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Takacs, Axel Marc Oaks. 2019. Imagining Forth the Incarnation: A Theo-Poetics of the Flesh. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard Divinity School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40615598 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&'&'%!()*+,!+,-!"'.$*'$+&)'/! 0!1,-)23)-+&.4!)5!+,-!(6-4,! ! "!#$%%&'()($*+!,'&%&+(&#! -.! "/&0!1)'2!3)4%!5)4)2%! (*! 56&!7)280(.!*9!:)';)'#!<$;$+$(.!=26**0! ! $+!,)'($)0!9809$00>&+(!*9!(6&!'&?8$'&>&+(%! 9*'!(6&!#&@'&&!*9! <*2(*'!*9!56&*0*@.! $+!(6&!%8-A&2(!*9! B*>,)')($;&!56&*0*@.! ! :)';)'#!C+$;&'%$(.! B)>-'$#@&D!1)%%)268%&((%! ! ",'$0!EFGH! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! I!EFGH!"/&0!1)'2!3)4%!5)4)2%! "00!'$@6(%!'&%&';&#J! #"$$%&'('")*!+,-"$)&.!/&(*0"$!12!34))*%56!78! +9%4!:(&0!;(<$!=(<(0$! ! !"#$%&%&$'()*+,'+,-'!&.#*&#+%)&/' 0'1,-)23)-+%.4')5'+,-'(6-4,' +>$'&(0'! ! =?"$!,"$$%&'('")*!"$!(*!%9%&0"$%!"*!0)@A(&('"-%!'?%)4)B5!>%'C%%*!'C)!A&%D@),%&*!'%9'E(4! '&(,"'")*$6!)*%!F$4(@"0!'?%!)'?%&!3?&"$'"(*2!F!&%(,!'?%$%!'&(,"'")*$!')B%'?%&6!"*'%&&%4"B")E$456!"*!$%(&0?! )G!0&"'"0(4!(*,!%@>),"%,!0)*$'&E0'"-%!"*'%&A&%'('")*$!C"'?!(!-"%C!')!)E&!0)*'%@A)&(&5!C)&4,2!=?%! -

OSMANLI'da Ilimler Dizisi 13

OSMANLI'DA iLiMLER DiZiSi 13 uf Editörler ERCAN ALKAN OSMAN SACiDARI i SAR Y A·Y I NLARI iSAR Yayınları 115 Osmanlı'da ilimler Dizisi ı 3 Osmanlı'da ilm-i Tasawuf Editörler Ercan Alkan Osman Sacid Arı 1. Baskı, Aralık 2018, istanbul ISBN 978-605-9276·12-2 Yayına Hazır lı k M. Fatih Mintas ömer Said Güler Kitap Tasarım: Salih Pu lcu Tasarım Uygulama: Recep Önder Baskı·Cilt Elma Bas ı m Halkalı Cad. No: 162/7 SefakOy Kücükcekmece J Istanbul Tel: +90 (212) 697 30 30 Matbaa Sertifıka No: 12058 © ISAR Yay ı nları T.C. KOltür ve Turizm Bakar:ılı~ı Sertlfıka No:·32581 Botan yayın hakları saklıdır. Bilimsel araştırma ve tanıtım icin yapılacak kısa alıı:ıtılar dışında·; yayıncının yazılı Izni olmadan hicbir yolla çcıga'ttııamaz: iSAR Yay ınl a rı Selamı Ali Mah. Fıstıka~ac ı Sok. No: 22 Osküdar 1 istanbul Tel: +90 (216) 310 99 23 ı Belgegecer: +90 (216) 391 26 33 www.isaryaylnlari.com [email protected] Katalog Bilgileri Osmanl ı 'da ilm-i Tasawuf 1ed. Ercan Alkan· Osman Sacid Arı ı istanbul 2018 (1.bs.) i iSAR Yay ın ları- 15/ Osmanlı'da Ilimler Dizisi · 3 I ISBN: 978-605-9276-12·2116.5 x 24 cm. - 863 s. 11. Tasawufve Tarlkatler_ Osmanlı Devleti 2 . Sosyal Yasam ve Gelenekler 3. ilimlerTarıhi Confluence of the Spiritual and the Worldly: Interactions of the Khalwati-Gulshanis and Egyptian Sufis with Political Authority in Sixteenth Century Egypt Side Eınre Doç. Dr., Texas A & M University. Carefully crafred descriptions of the public behavior of Sufis and depictions of how holy men ought to behave in the presence of rulers can be fo und in an eclectic body of early modem Ottoman Turkish and Arabic narratives.