Fungi As Source of Inspiration in Contemporary Art Corrado Nai1,2* and Vera Meyer1*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Years in Washington. Life and Scenes in the National Capital, As a Woman Sees Them

Library of Congress Ten years in Washington. Life and scenes in the National Capital, as a woman sees them Mary Clemmer Ames TEN YEARS IN WASHINGTON. LIFE AND SCENES IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL, AS A WOMAN SEES THEM. 486 642 BY MARY CLEMMER AMES, Author of “Eirene, or a Woman's Right,” “Memorials of Alice and Phœbe Cary,” “A Woman's Letters from Washington,” “Outlines of Men, Women and Things,” etc. FULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH THIRTY FINE ENGRAVINGS, AND A PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR ON STEEL. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON COPYRIGHT 1873 No 57802 HARTFORD, CONN.: A. D. WORTHINGTON & CO. M. A. PARKER & CO., Chicago, Ills. F. DEWING & CO., San Francisco, Cal. 1873. no. 2 F1?8 ?51 Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1873, by A. D. WORTHINGTON & CO., In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. Case Lockwood & Brainard, PRINTERS AND BINDERS, Cor. Pearl and Trumbull Sts., Hartford, Conn. Ten years in Washington. Life and scenes in the National Capital, as a woman sees them http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.28043 Library of Congress I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness, in gathering the materials of this book, to Mr. A. R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress; to Col. F. Howe; to the Chiefs of the several Government Bureaus herein described; to Mr. Colbert Lanston of the Bureau of Pensions; to Mr. Phillips, of the Bureau of Patents; and to Miss Austine Snead. M. C. A. TO Mrs. HAMILTON FISH, TO Mrs. ROSCOE CONKLING, OF NEW YORK, TWO LADIES, WHO, IN THE WORLD, ARE YET ABOVE IT,—WHO USE IT AS NOT ABUSING IT, WHO EMBELLISH LIFE WITH THE PURE GRACES OF CHRISTIAN WOMANHOOD, THESE SKETCHES OF OUR NATIONAL CAPITAL ARE SINCERELY Dedicated BY MARY CLEMMER AMES. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Rainian Uarter

e rainian uarter A JOURNAL OF UKRAINIAN AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Volume LXIV, Numbers 1-2 Spring-Summer 2008 This issue is a commemorative publication on the 75th anniversary of the Stalin-induced famine in Ukraine in the years 1932-1933, known in Ukrainian as the Holodomor. The articles in this issue explore and analyze this tragedy from the perspective of several disciplines: history, historiography, sociology, psychology and literature. In memory ofthe "niwrtlered millions ana ... the graves unknown." diasporiana.org.u a The Ukrainian uarter'7 A JOURNAL OF UKRAINIAN AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Since 1944 Spring-Summer 2008 Volume LXIV, No. 1-2 $25.00 BELARUS RUSSIA POLAND ROMANIA Territory of Ukraine: 850000 km2 Population: 48 millions [ Editor: Leonid Rudnytzky Deputy Editor: Sophia Martynec Associate Editor: Bernhardt G. Blumenthal Assistant Editor for Ukraine: Bohdan Oleksyuk Book Review Editor: Nicholas G. Rudnytzky Chronicle ofEvents Editor: Michael Sawkiw, Jr., UNIS Technical Editor: Marie Duplak Chief Administrative Assistant: Tamara Gallo Olexy Administrative Assistant: Liza Szonyi EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Anders Aslund Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Yaroslav Bilinsky University of Delaware, Newark, DE Viacheslav Brioukhovetsky National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Ukraine Jean-Pierre Cap Professor Emeritus, Lafayette College, Easton, PA Peter Golden Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Mark von Hagen Columbia University, NY Ivan Z. Holowinsky Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Taras Hunczak Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Wsewolod Jsajiw University of Toronto, Canada Anatol F. Karas I. Franko State University of Lviv, Ukraine Stefan Kozak Warsaw University, Poland Taras Kuzio George Washington University, Washington, DC Askold Lozynskyj Ukrainian World Congress, Toronto Andrej N. Lushnycky University of Fribourg, Switzerland John S. -

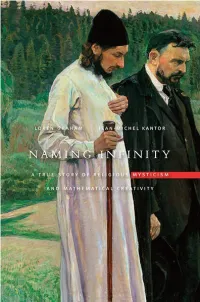

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

March 2010 Schools and Status Added Information

School Accountability Status for the 2009-10 School Year Based On 2008-09 School Year Data All Schools County/District/School 2009-10 School Year Status Subject Additional Information County: ALBANY ACHIEVEMENT ACAD CHARTER SCHOOL * ACHIEVEMENT ACAD CHARTER SCHOOL In Good Standing ALBANY CITY SD * MONTESSORI MAGNET SCHOOL In Good Standing * PINE HILLS ELEMENTARY SCHOOL In Good Standing * DELAWARE COMMUNITY SCHOOL In Good Standing * NEW SCOTLAND ELEMENTARY SCHOOL In Good Standing * NORTH ALBANY ACADEMY Improvement (year 1) - Basic Elementary-Middle Level English Continuing in Language Arts improvement * ALBANY SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES In Good Standing * EAGLE POINT ELEMENTARY SCHOOL In Good Standing * THOMAS S O'BRIEN ACAD OF SCI & TECH In Good Standing * GIFFEN MEMORIAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL Improvement (year 1) - Basic Elementary-Middle Level English Continuing in Language Arts improvement * WILLIAM S HACKETT MIDDLE SCHOOL Restructuring (advanced) - Focused Elementary-Middle Level English Continuing in Language Arts improvement ALBANY HIGH SCHOOL Restructuring (year 1) - Comprehensive Secondary-Level English Language Continuing in Arts improvement Secondary-Level Mathematics * ARBOR HILL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL In Good Standing * P J SCHUYLER ACHIEVEMENT ACADEMY In Good Standing * SHERIDAN PREP ACADEMY In Good Standing * MYERS MIDDLE SCHOOL In Good Standing ALBANY COMMUNITY CHARTER SCHOOL * ALBANY COMMUNITY CHARTER SCHOOL In Good Standing ALBANY PREP CHARTER SCHOOL All Schools Status- Alpha Order (County, District, School) Page 1 of 194 * This school receives Title I funding. Title I schools that are not in Good Standing must offer Supplemental Education Services. Title I Thursday, March 04, 2010 schools that are in Improvement (year 2), Corrective Action, or Restructuring must also offer Public School Choice, if available. -

Heritage As Process

Heritage as Process: Constructing the Historical Child’s Voice Through Art Practice TAYLOR, Rachel Emily Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/25151/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version TAYLOR, Rachel Emily (2018). Heritage as Process: Constructing the Historical Child’s Voice Through Art Practice. Doctoral, Sheffield Hallam University. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Heritage as Process: Constructing the Historical Child’s Voice Through Art Practice Rachel Emily Taylor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2018 Declaration I, Rachel Emily Taylor, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, consisting of a written thesis, a box containing artefacts from workshop sessions, two accompanying publications, field notes, two CDs containing films and audio tracks, and a website displaying visual material from the research, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub- Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. I declare that this submission is my own work and has not been submitted for any other academic award. The use of all materials from sources other than my own work has been properly and fully acknowledged. i “I wasn’t crying about mothers,” he said rather indignantly. “I was crying because I couldn’t get my shadow to stick on. -

Contents • Abbreviations • International Education Codes • Us Education Codes • Canadian Education Codes July 1, 2021

CONTENTS • ABBREVIATIONS • INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES • US EDUCATION CODES • CANADIAN EDUCATION CODES JULY 1, 2021 ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR ABBREVIATIONS FOR STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES STATES, TERRITORIES AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN AND CANADIAN PROVINCES PROVINCES PROVINCES AL ALABAMA OH OHIO AK ALASKA OK OKLAHOMA CANADA AS AMERICAN SAMOA OR OREGON AB ALBERTA AZ ARIZONA PA PENNSYLVANIA BC BRITISH COLUMBIA AR ARKANSAS PR PUERTO RICO MB MANITOBA CA CALIFORNIA RI RHODE ISLAND NB NEW BRUNSWICK CO COLORADO SC SOUTH CAROLINA NF NEWFOUNDLAND CT CONNECTICUT SD SOUTH DAKOTA NT NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DE DELAWARE TN TENNESSEE NS NOVA SCOTIA DC DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA TX TEXAS NU NUNAVUT FL FLORIDA UT UTAH ON ONTARIO GA GEORGIA VT VERMONT PE PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND GU GUAM VI US Virgin Islands QC QUEBEC HI HAWAII VA VIRGINIA SK SASKATCHEWAN ID IDAHO WA WASHINGTON YT YUKON TERRITORY IL ILLINOIS WV WEST VIRGINIA IN INDIANA WI WISCONSIN IA IOWA WY WYOMING KS KANSAS KY KENTUCKY LA LOUISIANA ME MAINE MD MARYLAND MA MASSACHUSETTS MI MICHIGAN MN MINNESOTA MS MISSISSIPPI MO MISSOURI MT MONTANA NE NEBRASKA NV NEVADA NH NEW HAMPSHIRE NJ NEW JERSEY NM NEW MEXICO NY NEW YORK NC NORTH CAROLINA ND NORTH DAKOTA MP NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS JULY 1, 2021 INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION CODES International Education RN/PN International Education RN/PN AFGHANISTAN AF99F00000 CHILE CL99F00000 ALAND ISLANDS AX99F00000 CHINA CN99F00000 ALBANIA AL99F00000 CHRISTMAS ISLAND CX99F00000 ALGERIA DZ99F00000 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS CC99F00000 ANDORRA AD99F00000 COLOMBIA -

Porcellian Club Veterans

Advocates for Harvard ROTC H PORCELLIAN CLUB MEMBER VETERANS As a result of their military service, Crimson warriors became part of a “Band of Brothers”. The following is an illustrative but not exhaustive listing of military oriented biographies of veterans whose initial exposure to non-family “brotherhood” were as members of various social and final clubs as undergraduates at Harvard. CIVIL WAR - HARVARD COLLEGE BY CLASS 18 34 Major General Henry C. Wayne CSA Born in Georgia – Georgia Militia Infantry Henry was the son of a lawyer and US congressman from Georgia who was later appointed as justice to the US Supreme Court by President Andrew Jackson. He prepared at the Williston School in Northampton (MA) for Harvard where he was member of the Porcellian Club. In his junior year at Harvard, he received and accepted an appointment to West Point where he graduated 14th out of 45 in 1838. Among his class mates at West Point were future flag officers: Major General Irvin McDowell USA who was defeated at the 1st battle of Bull Run, General P.G.T. Beauregard CSA who was the victor at the1st battle of Bull Run as well as numerous other major Civil War engagements and Lt. General William J. Hardee CSA who served in both Mexican War and throughput the Civil War. After West Point, Henry was commissioned as a 2nd LT and served for 3 years with the 4th US Artillery on the frontiers border of NY and ME during a border dispute with Canada. He then taught artillery and cavalry tactics at West Point for 5 years before joining General Winfield Scott’s column from Vera Cruz to Mexico City during in the Mexican War. -

Mathematics of the Gateway Arch Page 220

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society ABCD springer.com Highlights in Springer’s eBook of the American Mathematical Society Collection February 2010 Volume 57, Number 2 An Invitation to Cauchy-Riemann NEW 4TH NEW NEW EDITION and Sub-Riemannian Geometries 2010. XIX, 294 p. 25 illus. 4th ed. 2010. VIII, 274 p. 250 2010. XII, 475 p. 79 illus., 76 in 2010. XII, 376 p. 8 illus. (Copernicus) Dustjacket illus., 6 in color. Hardcover color. (Undergraduate Texts in (Problem Books in Mathematics) page 208 ISBN 978-1-84882-538-3 ISBN 978-3-642-00855-9 Mathematics) Hardcover Hardcover $27.50 $49.95 ISBN 978-1-4419-1620-4 ISBN 978-0-387-87861-4 $69.95 $69.95 Mathematics of the Gateway Arch page 220 Model Theory and Complex Geometry 2ND page 230 JOURNAL JOURNAL EDITION NEW 2nd ed. 1993. Corr. 3rd printing 2010. XVIII, 326 p. 49 illus. ISSN 1139-1138 (print version) ISSN 0019-5588 (print version) St. Paul Meeting 2010. XVI, 528 p. (Springer Series (Universitext) Softcover ISSN 1988-2807 (electronic Journal No. 13226 in Computational Mathematics, ISBN 978-0-387-09638-4 version) page 315 Volume 8) Softcover $59.95 Journal No. 13163 ISBN 978-3-642-05163-0 Volume 57, Number 2, Pages 201–328, February 2010 $79.95 Albuquerque Meeting page 318 For access check with your librarian Easy Ways to Order for the Americas Write: Springer Order Department, PO Box 2485, Secaucus, NJ 07096-2485, USA Call: (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER Fax: 1-201-348-4505 Email: [email protected] or for outside the Americas Write: Springer Customer Service Center GmbH, Haberstrasse 7, 69126 Heidelberg, Germany Call: +49 (0) 6221-345-4301 Fax : +49 (0) 6221-345-4229 Email: [email protected] Prices are subject to change without notice. -

Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking About Modernity

Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking about Modernity TABLE OF CONTENTS “Give Me A Wilderness or A City”: George Bellows’s Rural Life ................................................ 2 Francis Criss: Locating Monuments, Locating Modernity ............................................................ 6 Seeing Beyond: Approaches to Teaching Salvador Dalí’s Appollinaire ............................. 10 “On the Margins of Written Poetry”: Pedro Figari ......................................................................... 14 Childe Hassam: American Impressionist and Preserver of Nature ..................................... 18 Subtlety of Line: Palmer Hayden’s Quiet Activism ........................................................................ 22 Modernist Erotica: André Kertész’s Distortion #128 ................................................................... 26 Helen Levitt: In the New York City Streets ......................................................................................... 31 Happening Hats: Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Le chapeau épinglé .............................................. 35 Diego Rivera: The People’s Painter ......................................................................................................... 39 Diego Rivera: El Pintor del Pueblo ........................................................................................................... 45 Household Modernism, Domestic Arts: Tiffany’s Eighteen-Light Pond Lily Lamp .... 51 Marguerite Zorach: Modernism’s Tense Vistas .............................................................................. -

Notes on the Narrative of Three Guatemalan Authors

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 8-2014 Nationalism, Universality, and Globalization: Notes on the Narrative of Three Guatemalan Authors Marcie Noble Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, and the Latin American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noble, Marcie, "Nationalism, Universality, and Globalization: Notes on the Narrative of Three Guatemalan Authors" (2014). Dissertations. 310. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/310 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM, UNIVERSALITY, AND GLOBALIZATION: NOTES ON THE NARRATIVE OF THREE GUATEMALAN AUTHORS by Marcie Noble A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Spanish Western Michigan University August 2014 Doctoral Committee: Michael Millar, Ph.D., Chair Antonio Isea, Ph.D. Benjamín Torres, Ph.D. Kristina Wirtz, Ph.D. NATIONALISM, UNIVERSALITY, AND GLOBALIZATION: NOTES ON THE NARRATIVE OF THREE GUATEMALAN AUTHORS Marcie Noble, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2014 This dissertation examines various works of literature produced by three Guatemalan authors: Miguel Ángel Asturias (1899-1974), Augusto Monterroso (1921- 2003), and Rodrigo Rey Rosa (1958) in order to trace a trajectory in the narrative written by Guatemalans from a nationally focused literature to one that is increasingly global. The first chapter provides an overview of the study and clarifies the terminology applied throughout the dissertation. -

ALEXANDER CALDER SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY PERIODICALS 2019 Chapman, Lara

ALEXANDER CALDER SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY PERIODICALS 2019 Chapman, Lara. “Examining the Void at ‘Calder-Picasso’” (The Musée National Picasso exhibition review). TL Magazine, 25 February 2019. https://tlmagazine.com/examining-the-void-at-calder-and-picasso/ Garrigues, Manon. “The Calder-Picasso Exhibition is Opening in Paris Today” (The Musée National Picasso exhibition preview). Vogue, 19 February 2019. https://www.vogue.fr/fashion-culture/article/the-calder- picasso-exhibition-is-opening-in-paris-today Heinrich, Will. “’The World According to’” (exhibition review). The New York Times, 1 March 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/01/arts/design/what-to-see-in-new-york-art-galleries-right-now.html Schneider, Tim. “How a Legendary Alexander Calder Installation Got Ensnated in Sear’s Tortuous Bankruptcy Saga.” Artnet News, 17 January 2019. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/calder-sears- bankruptcy-1441741 Tattoli, Chantel. “Celebrating Pablo Picasso and Alexander Calder’s Symbiosis” (Musée Picasso exhibition review). Architectural Digest, 13 February 2019. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/calder-picasso- paris-show 2018 Goukassian, Elena. “US Army Teams Up with Conservators to Preserve Outdoor Art.” Hyperallergic, 6 April 2018. https://hyperallergic.com/434513/us-army-teams-up-with-conservators-to-preserve-outdoor-art/ Alexander Calder: Selected Bibliography – Periodicals 2 Grace, Anne and Elizabeth Hutton Turner. “Alexander Calder: Radical Inventor.” The Magazine of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (September–December 2018): 4–7, illustrated. Pes, Javier. “Calder’s Home Deep in the French Countryside Opens Its Doors to the Next Artists in a Starry List of Residents.” Artnet News, 26 January 2018. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/calder-home-french- countryside-artist-residency-1206770 Rower, Alexander S.