Harn Museum of Art Instructional Resource: Thinking About Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton Easter Fiel

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Ten Years in Washington. Life and Scenes in the National Capital, As a Woman Sees Them

Library of Congress Ten years in Washington. Life and scenes in the National Capital, as a woman sees them Mary Clemmer Ames TEN YEARS IN WASHINGTON. LIFE AND SCENES IN THE NATIONAL CAPITAL, AS A WOMAN SEES THEM. 486 642 BY MARY CLEMMER AMES, Author of “Eirene, or a Woman's Right,” “Memorials of Alice and Phœbe Cary,” “A Woman's Letters from Washington,” “Outlines of Men, Women and Things,” etc. FULLY ILLUSTRATED WITH THIRTY FINE ENGRAVINGS, AND A PORTRAIT OF THE AUTHOR ON STEEL. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON COPYRIGHT 1873 No 57802 HARTFORD, CONN.: A. D. WORTHINGTON & CO. M. A. PARKER & CO., Chicago, Ills. F. DEWING & CO., San Francisco, Cal. 1873. no. 2 F1?8 ?51 Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1873, by A. D. WORTHINGTON & CO., In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. Case Lockwood & Brainard, PRINTERS AND BINDERS, Cor. Pearl and Trumbull Sts., Hartford, Conn. Ten years in Washington. Life and scenes in the National Capital, as a woman sees them http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.28043 Library of Congress I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness, in gathering the materials of this book, to Mr. A. R. Spofford, Librarian of Congress; to Col. F. Howe; to the Chiefs of the several Government Bureaus herein described; to Mr. Colbert Lanston of the Bureau of Pensions; to Mr. Phillips, of the Bureau of Patents; and to Miss Austine Snead. M. C. A. TO Mrs. HAMILTON FISH, TO Mrs. ROSCOE CONKLING, OF NEW YORK, TWO LADIES, WHO, IN THE WORLD, ARE YET ABOVE IT,—WHO USE IT AS NOT ABUSING IT, WHO EMBELLISH LIFE WITH THE PURE GRACES OF CHRISTIAN WOMANHOOD, THESE SKETCHES OF OUR NATIONAL CAPITAL ARE SINCERELY Dedicated BY MARY CLEMMER AMES. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17)

MSA 7 Program (Draft 10.17) Session A: Thursday, 3:00–5:00 pm Panel 1. Manuscript Research and Modernist Studies Newberry Library, 60 W. Walton St. Bus transportation between the Newberry Library and the conference hotel is available ORGANIZER AND CHAIR: John Timberman Newcomb, University of Illinois – Urbana-Champaign George Bornstein, University of Michigan Laura Milsk Fowler, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Lawrence Rainey, University of York Seminars 2. Modernism at Home Chicago Ballroom A—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Gail McDonald, University of North Carolina – Greensboro Dawn Blizard, Brown University Allison Carey, Cannon School Dorothy Chansky, Texas Tech University Bradley Clissold, Memorial University of Newfoundland Barbara Green, University of Notre Dame Kevin Hagopian, Pennsylvania State University Amy E. C. Linneman, Indiana University Marion McInnes, DePauw University Phoebe Putnam, Harvard University Jin Xiaotian Skye, University of Hong Kong Eve Sorum, University of Michigan 3. The Author Business Chicago Ballroom B—No auditors, please ORGANIZER: Alison Booth, University of Virginia Patrick Collier, Ball State University Marianne Cotugno, Miami University Maria Fackler, Yale University Julia Friedman, Brown University Peter Kalliney, University of South Florida Kurt M. Koenigsberger, Case Western Reserve University Bette London, University of Rochester Randi Saloman, Yale University Lisa Stein, Ohio University Catherine Turner, College Misericordia Andrea Zemgulys, University of Michigan 4. Anthropological -

Rainian Uarter

e rainian uarter A JOURNAL OF UKRAINIAN AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Volume LXIV, Numbers 1-2 Spring-Summer 2008 This issue is a commemorative publication on the 75th anniversary of the Stalin-induced famine in Ukraine in the years 1932-1933, known in Ukrainian as the Holodomor. The articles in this issue explore and analyze this tragedy from the perspective of several disciplines: history, historiography, sociology, psychology and literature. In memory ofthe "niwrtlered millions ana ... the graves unknown." diasporiana.org.u a The Ukrainian uarter'7 A JOURNAL OF UKRAINIAN AND INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS Since 1944 Spring-Summer 2008 Volume LXIV, No. 1-2 $25.00 BELARUS RUSSIA POLAND ROMANIA Territory of Ukraine: 850000 km2 Population: 48 millions [ Editor: Leonid Rudnytzky Deputy Editor: Sophia Martynec Associate Editor: Bernhardt G. Blumenthal Assistant Editor for Ukraine: Bohdan Oleksyuk Book Review Editor: Nicholas G. Rudnytzky Chronicle ofEvents Editor: Michael Sawkiw, Jr., UNIS Technical Editor: Marie Duplak Chief Administrative Assistant: Tamara Gallo Olexy Administrative Assistant: Liza Szonyi EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Anders Aslund Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Yaroslav Bilinsky University of Delaware, Newark, DE Viacheslav Brioukhovetsky National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Ukraine Jean-Pierre Cap Professor Emeritus, Lafayette College, Easton, PA Peter Golden Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Mark von Hagen Columbia University, NY Ivan Z. Holowinsky Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Taras Hunczak Rutgers University, Newark, NJ Wsewolod Jsajiw University of Toronto, Canada Anatol F. Karas I. Franko State University of Lviv, Ukraine Stefan Kozak Warsaw University, Poland Taras Kuzio George Washington University, Washington, DC Askold Lozynskyj Ukrainian World Congress, Toronto Andrej N. Lushnycky University of Fribourg, Switzerland John S. -

Representations of the Female Nude by American

© COPYRIGHT by Amanda Summerlin 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BARING THEMSELVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE FEMALE NUDE BY AMERICAN WOMEN ARTISTS, 1880-1930 BY Amanda Summerlin ABSTRACT In the late nineteenth century, increasing numbers of women artists began pursuing careers in the fine arts in the United States. However, restricted access to institutions and existing tracks of professional development often left them unable to acquire the skills and experience necessary to be fully competitive in the art world. Gendered expectations of social behavior further restricted the subjects they could portray. Existing scholarship has not adequately addressed how women artists navigated the growing importance of the female nude as subject matter throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I will show how some women artists, working before 1900, used traditional representations of the figure to demonstrate their skill and assert their professional statuses. I will then highlight how artists Anne Brigman’s and Marguerite Zorach’s used modernist portrayals the female nude in nature to affirm their professional identities and express their individual conceptions of the modern woman. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I could not have completed this body of work without the guidance, support and expertise of many individuals and organizations. First, I would like to thank the art historians whose enlightening scholarship sparked my interest in this topic and provided an indispensable foundation of knowledge upon which to begin my investigation. I am indebted to Kirsten Swinth's research on the professionalization of American women artists around the turn of the century and to Roberta K. Tarbell and Cynthia Fowler for sharing important biographical information and ideas about the art of Marguerite Zorach. -

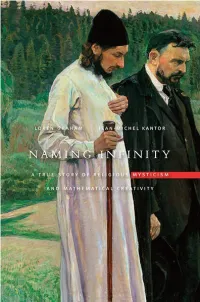

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Rocky Neck Historic Art Trail Gloucester, Massachusetts

Rocky Neck Historic Art Trail Gloucester, Massachusetts Trail Site 1 Above 186 to 220 East Main St. Rocky Banner Hill Neck 1 Smith Banner The high ridge, or bluff, rising above the Smith Cove inlet on the east side of Cove Hill Gloucester Harbor, is called “Banner Hill.” So named after the Wonson brothers Stevens Lane raised a flag there at the outbreak of the Civil War, it commands a panoramic scene, with the jewel of Rocky Neck’s wharves and houses sitting in the center R a P c k l i of the harbor, framed by the buildings and steeples of the central city beyond. f f S During the second half of the 19th Century and the first decades of the 20th, t many of America’s most important artists journeyed to Gloucester to experience the amazing coastal scenery in this fishing port composed of high hills overlook - DIRECTIONS: ing a protected and deep harbor. Banner Hill afforded perhaps the most dramatic From the end of Rte. 128 (second traffic light) go straight up over hill. Follow East of these views. Main Street about 5/8 mile just past East Gloucester Square. Banner Hill rises up Attracted to Gloucester by its reputation for authentic New England beauty, as along the left side of the road for a few conveyed in the paintings of famed 19th century artists Fitz H. Lane and Winslow hundred yards along Smith Cove, above Homer, the preeminent landscape painters of the American Impressionist move - the section of 186 to 220 East Main Street, ment in the 1890s, including Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, Frank Duveneck, just across from Beacon Marine boat yard and extending southwest, topped by several and John Twachtman, created masterpieces from the perspective of Banner Hill. -

Pressionism,Which Was Haven't Lookedat in a Long Time," Stillgoing Strongafter Maciejunessaid "It's Interestingto See World Wari

+ aynm Feran "Precisionism in DispatchEntertainment Reporter America■ 1915-1941: ReorderingReality" N 1915, ARTISTMARcEL DUCHAMP will openSunday proclaimedthe UnitedStates and continue "thecountry of theart of the throughJuly 4 at future." the Columbus "Look atthe skyscrapers!"he Museum of Art, said"Has Europe anything to 480 E. BroadSt. show more beautifulthan these?" Tourswill begiven The Frenchman's words at noonMay 26 and focusedattention on what was June 16, and 2 p.m. e seen as auniquely American artistic May 28and June movement. 18. Call 221-6801. "Precisionismin America1915-1941: ReorderingReality" is "thefirst major study of precisionismin a long time,"said NannetteMaciejunes, seniorcurator at the ColumbusMuseum of Art. "Precisionismis verytied up withthe search for a ABoVE:The cleanlines of rural unique Americanidentity," scenes: Bucks OHmJy Barn(1918) t she said"It wasabout the " by Charles Sheeler(1883-1965) tyingof a ruralpast to the mechanicalfuture. A lot of LEFT:The forms of the machine • people in the'.20s called it agewith classicalclarity: A.ugussin 'thetrue American art.' " andNu:oletle (1923)by Charles By the timeprecisionism Demuth (1883-1935) arrived,the United States waswell on itsway froma - ruralsociety to a nationof show,which began at theMontclair Art 0 big citieswith skyscrapers Museumin New Jerseyand features andhomes withmodern works by 26 artistsfrom almost 30 I marvelssuch asvacuum institutionsand private collections. cleanersand washing "Thisshow is so criticalto us," � �es. Maciejunes said"(Ferdinand) Rowald !'!. Painters and was majora collector in thisarea. He saw photographersassociated theparallel between cubism and �� withprecisionism included precisionism, andhe collected both." iii CharlesDemuth, Morton Althoughmany works in theNew I Scharnberg,Charles Sheeler Jerseyexhibition are not availablefor the s andJoseph Stella. -

Knife Grinder Date: 1912-1913 Creator: Umberto Boccioni, Italian, 1882-1916 Title: Dynamism of a Soccer Player Work Type: Painting Date: 1913 Cubo-Futurism

Creator: Malevich, Kazimir, Russian, 1878- 1935 Title: Knife Grinder Date: 1912-1913 Creator: Umberto Boccioni, Italian, 1882-1916 Title: Dynamism of a Soccer Player Work Type: Painting Date: 1913 Cubo-Futurism • A common theme I have been seeing in the different Cubo- Futurism Paintings is a wide variety of color and either solid formations or a high amount of single colors blended or layered without losing the original color. I sense of movement is also very big, the Knife Grinder shows the action of grinding by a repeated image of the hand, knife, or foot on paddle to show each moment of movement. The solid shapes and designs tho individually may not seem relevant to a human figure all come together to show the act of sharpening a knife. I Love this piece because of the strong colors and repeated imagery to show the act. • In the Dynamism of a soccer player the sense of movement is sort of around and into the center, I can imagine a great play of lights and crystal clarity of the ideas of the objects moving. I almost feel like this is showing not just one moment or one movement but perhaps an entire soccer game in the scope of the 2D canvas. Creator: Demuth, Charles, 1883-1935 Title: Aucassin and Nicolette Date: 1921 Creator: Charles Demuth Title: My Egypt Work Type: Paintings Date: 1927 Precisionism • Precisionism is the idea of making an artwork of another “artwork” as in a piece of architecture , or machinery. The artist renders the structure using very geometric and precise lines and they tend to keep an element of realism in their work. -

O'keefe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Heather Hole, “O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 2, no. 2 (Fall 2016), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1577. O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York Heather Hole, Assistant Professor, Simmons College Curated by: Ellen E. Roberts Exhibition schedule: Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, Florida, February 18– May 15, 2016; Portland Museum of Art, Maine, June 23–September 18, 2016 Exhibition catalogue: Ellen E. Roberts, O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York, exh. cat. West Palm Beach: Norton Museum of Art, 2016. 159 pp.; 100 color illus. Hardcover $40.00 (ISBN: 9780943411231) O’Keeffe, Stettheimer, Torr, Zorach: Women Modernists in New York at the Portland Museum of Art brings together the art of four American women artists who worked in New York City from about 1910 to 1935. The stated purpose of the exhibition is to examine the effects of gender on the careers, work, and reception of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944), Helen Torr (1886–1967), and Marguerite Zorach (1887– 1968) in parallel, while also arguing that femininity did not define their various approaches to modernism. These four artists are also analyzed within two specific, shared circumstances: women’s increasing political and social freedoms in the early-twentieth- century United States and the New York avant-garde art world. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue give new context to the substantial existing scholarship on O’Keeffe and gender, and offer valuable insights into the less studied lives and artistic contributions of Stettheimer, Torr, and Zorach.