Cyber Security and Global Interdependence: What Is Critical? Cyber Security and Global Interdependence: What Is Critical?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Def Leppard – 02

DEF LEPPARD – 02. Juli 2019 – Berlin – Zitadelle Spandau – Support: EUROPE – JOHN DIVA and the Rockets of Love – Text und Fotos: Holger Ott Im Zeichen des Retro rufen die Bands der guten alten 80er Jahre und die Fans pilgern in die Zitadelle Spandau von Berlin. Das alte Gemäuer ist beliebt, gibt es neben sehr guter Akustik auch von allen Plätzen eine hervorragende Sicht auf die schöne große Bühne. Das Wetter spielt heute auch mit. Weder zu heiß noch zu kalt und bei einem kleinen Lüftchen lässt es sich einige Stunden aushalten. Dieses Stehvermögen braucht das Publikum, denn mit drei Bands stehen, abgesehen von den Umbaupausen, geschlagene drei Stunden Musik auf dem Programm Eröffnet wird der Abend von einer, mir bis dato, unbekannten Band. JOHN DIVA mit seinen 'Rockets of Love' geben sich die Ehre und präsentieren in dreißig Minuten eine beeindruckende musikalische und optische Darbietung unter dem Motto: „Mama said, Rock is dead". Frontman JOHN DIVA und seine Mannen turnen in extravagantem Outfit über die Bühne. Schön grell und bunt darf es sein und sieht man dazu DIVAS passenden Hüftschwung, weiß der Fan sofort, dass es hier nur um Sex, Drugs and Rock 'n' Roll geht. Ohne Zweifel, die Truppe ist gut und rockt auch richtig fett ab. Also, im Auge behalten. Ein gelungener Einstand in den heutigen Abend. Zu EUROPE muss man nicht viel sagen. JOEY TEMPEST ist in top Form und schmettert seine bekanntesten Songs in die Menge. Das Gedränge vor der Bühne wird größer und der Hype wächst mit jedem Song ihrer einstündigen Show. Leider fällt durch die Supporterstellung einiges unter den Tisch, aber Hits wie „Carrie", „Superstitius" und natürlich das abschließende "The Final Countdown" reißen wieder alles heraus. -

Heavy Karaoke

Heavy Karaoke Mood Media Finland Oy Väinö Tannerin Tie 3, 01510 Vantaa, FINLAND Vaihde: 010 666 2230 Helpdesk: 010 666 2233 fi.all@ moodmedia.com www.moodmedia .fi Kch = The Karaoke Channel Hevikaraoke KAPPALE ESITTÄJÄ ID TOIM. (OH) PRETTY WOMAN VAN HALEN 20917 Kch 18 AND LIFE SKID ROW 20331 18 AND LIFE SKID ROW 20510 Kch 2 MINUTES TO MIDNIGHT IRON MAIDEN 20135 5 MINUTES ALONE PANTERA 20277 A MAN I'LL NEVER BE BOSTON 20061 A NEW LEVEL PANTERA 20278 A VOICE IN THE DARK TACERE 20360 A WHITER SHADE OF PALE PROCOL HARUM 20306 ACE OF SPADES MOTÖRHEAD 20827 Kch ACES HIGH IRON MAIDEN 20136 ADDICTED TO LOVE ROBERT PALMER 20320 ADIDAS KORN 20695 Kch AENIMA TOOL 20662 Kch AERIALS (RADIO VERSION) SYSTEM OF A DOWN 20841 Kch AGAIN ALICE IN CHAINS 20512 Kch AIN'T TALKIN' 'BOUT LOVE VAN HALEN 20619 Kch ALIVE PEARL JAM 20294 ALL ALONG THE WATCHTOWER JIMI HENDRIX 20158 ALL FOR YOU CHEAT CODE 20068 ALL HALLOWS EVE TYPE O NEGATIVE 20689 Kch ALL MY LOVE LED ZEPPELIN 20637 Kch ALL RIGHT NOW FREE 20118 ALL THE SMALL THINGS BLINK 182 20048 ALMOST EASY (RADIO VERSION) AVENGED SEVENFOLD 20955 Kch ALONE AGAIN DOKKEN 20550 Kch AMARANTH NIGHTWISH 20433 AMORPHOUS EXLIBRIS 20964 AND IT STONED ME VAN MORRISON 20701 Kch AND THE CRADLE WILL ROCK VAN HALEN 20394 AND THE CRADLE WILL ROCK VAN HALEN 20786 Kch ANGRY AGAIN MEGADETH 20863 Kch ANIMAL DEF LEPPARD 20093 ANIMAL DEF LEPPARD 20767 Kch ANIMAL PEARL JAM 20295 ANIMAL (FUCK LIKE A BEAST) W.A.S.P. -

Def Leppard “Hysteria” By: Kyle Harman

Def Leppard “Hysteria” By: Kyle Harman Hysteria would be a fitting name for the album thought Def Leppard drummer Rick Allen, following his 1984 injury from a horrific car accident that resulted in the loss of his left arm, Hysteria was the perfect title to describe the worldwide media coverage that followed the band between the years of 1984 and 1987. The album was the last to feature the late Steve Clark and his role of lead guitarist due to an overdose in the year of 1992. In the very prime years of glam metal in the late 80’s at the dawn of grunge genre about to begin, Def Leppard delivered the bands bestselling album to date with selling 25 million copies worldwide and 12 million in the US alone. The three year recording process of Hysteria was painstaking with the accident of drummer Rick Allen, and with producers coming and going left the band with the perfect example of sometimes patience truly does pay off. A unique recording process took place where each member recorded their own recordings at separate times, allowing each member to focus on their own performance on the album. The original intent of the album was to be a rock version of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, with the desire of having every song off the album as a possible hit single. The end result of the album was impressive to say the least with 7 singles released off the single album alone. The album recording sessions were painstaking at times, “Animal” consisted of 2 and a half years to produce its final product, where “Pour Some Sugar On Me” was finished within two weeks. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MARCH 6, 2018 No. 39 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was And guess what? The cynics were brought to him and he rejected them, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- right, and Congress has taken no ac- saying that he wanted to eliminate pore (Mr. HARPER). tion. There have been a few attempts, various types of legal immigration ave- f but the reality is that Congress has not nues used by people, especially people passed a bill, and the opportunities for of color and people from the developing DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO us to pass a bill are dwindling. world. Without these massive cuts to TEMPORE How did we get here? How is it that legal immigration, the President just The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we always end up here when it comes wasn’t interested. fore the House the following commu- to immigration? And we offered him money for his nication from the Speaker: Well, it has been a failure of both silly, mindless, stupid, dimwitted, rac- WASHINGTON, DC, parties to act, to compromise, and to ist wall, but he rejected that, too. March 6, 2018. legislate. But let’s be honest, the Presi- In the end, this is not about Dream- I hereby appoint the Honorable GREGG dent doesn’t want these immigrants in ers, it is not about the wall, it is not HARPER to act as Speaker pro tempore on this country, and Republicans in Con- about border security. -

1. Rush - Tom Sawyer 2

1. Rush - Tom Sawyer 2. Black Sabbath - Iron Man 3. Def Leppard - Photograph 4. Guns N Roses - November Rain 5. Led Zeppelin - Stairway to Heaven 6. AC/DC - Highway To Hell 7. Aerosmith - Sweet Emotion 8. Metallica - Enter Sandman 9. Nirvana - All Apologies 10. Black Sabbath - War Pigs 11. Guns N Roses - Paradise City 12. Tom Petty - Refugee 13. Journey - Wheel In The Sky 14. Led Zeppelin - Kashmir 15. Jimi Hendrix - All Along The Watchtower 16. ZZ Top - La Grange 17. Pink Floyd - Another Brick In The Wall 18. Black Sabbath - Paranoid 19. Soundgarden - Black Hole Sun 20. Motley Crue - Home Sweet Home 21. Derek & The Dominoes - Layla 22. Rush - The Spirit Of Radio 23. Led Zeppelin - Rock And Roll 24. The Who - Baba O Riley 25. Foreigner - Hot Blooded 26. Lynyrd Skynyrd - Freebird 27. ZZ Top - Cheap Sunglasses 28. Pearl Jam - Alive 29. Dio - Rainbow In The Dark 30. Deep Purple - Smoke On The Water 31. Nirvana - In Bloom 32. Jimi Hendrix - Voodoo Child (Slight Return) 33. Billy Squier - In The Dark 34. Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here 35. Rush - Working Man 36. Led Zeppelin - Whole Lotta Love 37. Black Sabbath - NIB 38. Foghat - Slow Ride 39. Def Leppard - Armageddon It 40. Boston - More Than A Feeling 41. AC/DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 42. Ozzy Osbourne - Crazy Train 43. Aerosmith - Walk This Way 44. Led Zeppelin - Dazed & Confused 45. Def Leppard - Rock Of Ages 46. Ozzy Osbourne - No More Tears 47. Eric Clapton - Cocaine 48. Ted Nugent - Stranglehold 49. Aerosmith - Dream On 50. Van Halen - Eruption / You Really Got Me 51. -

I Don T Wanna Miss a Thing Armageddo

I don t wanna miss a thing armageddo Continue 1998 single Aerosmith For 1999 Mark Chesnutt album, see I don't want to miss a thing (album). I Don't Want to Miss a ThingSingle by Aerosmith from Armageddon: The AlbumB-side Animal Crackers Taste of India released on August 18, 1998 (USA) august 31, 1998 (UK) Genre Hard Rock Rock (1) Length4:59Label Columbia Hollywood Epic Songwriter (s)Diane Warren (s)Matt SerleticAerosmith singles chronology Taste of India (s)19 98) I Don't Want to Miss a Thing (1998) What Love Are You on (1998) Audio samplefilehelp I Don't Want to Miss The Thing Is a Power Ballad performed by American hard rock band Aerosmith for film about the 1998 film Armageddon, which starred the daughter of the vocalist Steven Tyler Liv Tyler. It's one of four songs performed by the band for the film, the other three of them What Love You're On, Come Together and Sweet Emotion. Written by Diane Warren, the song debuted at number one on the Us Billboard Hot 100, giving the band their first and only number one single in their home country. The song remained in its first week, from September 5 to September 26, 1998. It also peaked at number one in a matter of weeks in several other countries including Australia, Ireland and Norway. More than a million copies have been sold in the UK and reached number four on the UK Singles Chart. The song was covered by American country music singer Mark Chesnatt for his album of the same name. -

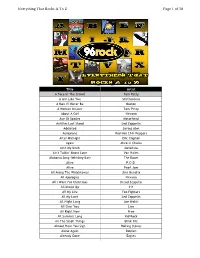

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 145 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 1999 No. 119 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. half of the Nation's uninsured children, Vice President has proposed. Instead of f and we must not forget the other half. expanding the program to include Mr. Speaker, last week Vice Presi- MORNING HOUR DEBATES those at 250 percent of poverty, my bill dent GORE brought renewed attention will follow New Jersey's example and The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the to this issue, reminding everyone that expand it to families at 350 percent of order of the House of January 19, 1999, the job is not done. In Los Angeles, he poverty. States that elect to increase the Chair will now recognize Members announced a plan he will be pursuing the eligibility level to 350 percent from lists submitted by the majority to make health insurance available to would receive increased Federal funds and minority leaders for morning hour every child in the country by the year to help meet the costs. debates. The Chair will alternate rec- 2005. ognition between the parties, with each I think it is important to note that In addition, my bill will include two party limited to not to exceed 30 min- the Vice President's observation that provisions to help boost enrollment in utes, and each Member except the ma- the State health insurance program the program. The first will provide in- jority leader, the minority leader or needs to be expanded is a view shared centives for States to pass laws by a the minority whip limited to not to ex- by many, if not every State in the date certain to authorize hospitals to ceed 5 minutes each, but in no event country. -

THE PROVING GROUNDS of ARMAGEDDON) Copyright © 2010 by (TWIN FORKS PUBLISHING)

The Proving Grounds of Armageddon Mark Childs (THE PROVING GROUNDS OF ARMAGEDDON) Copyright © 2010 by (TWIN FORKS PUBLISHING) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from the author. ISBN (XXXXXXXXXXXXX) 2 Also by Mark Childs The Devilution Series Devilution Rebelution Soulution Jaloopa – Home of the Poobah Baloo The Jaloopa Jalopy and the Funny Farm Forthcoming The Gate The Jaloopiter The Power of the Love of Power 3 DEDICATION As I near the halfway point of my life, I find myself reflecting on past events with greater frequency, especially those from the early years of my youth. Amongst my fondest memories are those of my grandmother, Pearl Furtah. She was, without a doubt, the best grandmother in the world, and for that reason, I dedicate this book to her. I doubt she would have approved of some of the content, but I’m certain she would have understood the message. 4 Humans are the only creatures on the face of the earth that allow emotions to override its sense of self- preservation. Deforestation is depleting our planets ability to protect itself, yet the process continues unabated. Smoking is a prescription for lung cancer yet millions continue to smoke. The governments of the world could stop the production of tobacco products but enormous tax revenues provide them with the justification they need to sit idly by. Obesity is no longer a problem, it is an epidemic, yet fast food chains continue to thrive. We, as a race, are accelerating toward the finish line of a race that began thousands of years ago. -

Def Leppard When Love & Hate Collide Mp3, Flac

Def Leppard When Love & Hate Collide mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: When Love & Hate Collide Country: Japan Released: 1995 Style: Hard Rock, Arena Rock, Pop Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1510 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1595 mb WMA version RAR size: 1235 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 224 Other Formats: MP3 MPC DMF AHX AC3 DXD MMF Tracklist Hide Credits When Love & Hate Collide 1 Arranged By [Strings] – Michael KamenBacking Vocals [Additional] – Stevie VannPiano – 4:16 Randy KerberProducer – Def LeppardProducer, Engineer – Pete Woodroffe Rocket (Remix) 2 7:06 Engineer – Nigel GreenProducer – Robert John "Mutt" Lange* Armageddon It (Remix) 3 7:43 Engineer – Nigel GreenProducer – Robert John "Mutt" Lange* When Love & Hate Collide (Original Demo) 4 6:09 Guitar [Final Solo] – Steve Clark Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Mercury Music Entertainment Co., Ltd. Distributed By – Mercury Music Entertainment Co., Ltd. Credits Written-By – Elliott*, Collen* (tracks: 2, 3), Savage*, Lange* (tracks: 2, 3), Clark* (tracks: 2, 3) Notes Tracks 2 and 3 never before released on CD. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (OBI): 4 988011 347337 Rights Society: JASRAC Matrix / Runout: PHCR-8338- 2K V IFPI L237 Mastering SID Code: IFPI L237 Mould SID Code: IFPI 4011 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Bludgeon LEPCD 14, When Love & Hate LEPCD 14, Def Leppard Riffola, UK 1995 852 401-2 Collide (CD, Single) 852 401-2 Mercury When Love & Hate Mercury, CDP 1515 Def Leppard Collide (CD, Single, Bludgeon CDP 1515 -

The Final Cut Plotting World Domination from Altoona

NOVEMBER 15, 1999 VOLUME 14 #4 The Final Cut Plotting world domination from Altoona Otherwise,CD/Tape/Culture analysis and commentary with D'Scribe, D'Drummer, Da Boy, D'Sebastiano's Doorman, Da Common Man, D' Big Man, Al, D'Pebble, Da Beer God and other assorted riff raff, D'RATING SYSTEM: 9.1-10.0 Excellent - BUY OR DIE! 4.1-5.0 Incompetent - badly flawed 8.1-9.0 Very good - worth checking out 3.1-4.0 Bad - mostly worthless 7.1-8.0 Good but nothing special 2.1-3.0 Terrible - worthless 6.1-7.0 Competent but flawed 1.1-2.0 Horrible - beyond worthless 5.1-6.0 Barely competent 0.1-1.0 Bottom of the cesspool abomination! I GUESS THIS ISSUE IS A LITTLE BIT LATE… I can’t offer any excuses, except that things at Cut headquarters have been hellaciously busy over the past few months, affording yours truly very little time to sit down and get this tome written up. But do not despair, this rag will continue on, even if only 3 or 4 times a year. But we’ll try to get it out a little more frequently, if our schedules allow us. Hopefully the contents within this issue are worth the long wait. SINCE IT HAS BEEN A LONG TIME BETWEEN ISSUES, I have built up a ton of takes I have to get out of my system, so please bear with me and deal with it… FIRST, MEMO TO THE ALTOONA CLUB SCENE: Stop the DAMN FIGHTING! Just about every ‘Toona live music nightspot has endured at least one slobberknocker in recent months, and it has to end! The post -Halloween Party free-for-all at Pellegrine’s was total BULLS**T!!! Because of idiots fighting, one nightspot is facing a -

Reframing the Disaster Genre in a Post-9/11 World

Wesleyan University The Honors College Reframing the Disaster Genre in a Post-9/11 World by Matthew James Connolly Class of 2009 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in Film Studies Middletown, Connecticut April, 2009 1 Acknowledgments To begin with, thank you to Scott Higgins. Your ―History of World Cinema‖ class made me want to become a Film Studies major. Your ―Cinema of Adventure and Action‖ course led me to the notion of writing a thesis on disaster cinema. And your intelligence, humor, patience, and unfaltering support as a thesis advisor has made the end product infinitely better and the journey all the more rewarding. Thank you to the Film Studies department: especially to Lisa Dombrowski for her perceptive, balanced, and always illuminating teaching; and to Jeanine Basinger, whose seemingly boundless understanding of film and her passion for sharing it with others has forever changed the way I think about movies. Thank you to all of the brilliant and inspiring professors I have had the pleasure and honor of learning from over my four years at Wesleyan, especially William Stowe, Sally Bachner, Henry Abelove, Claudia Tatinge Nascimentio, Mary-Jane Rubenstein and Renee Romano. Thank you to all of my beautiful and brilliant friends who have supported me throughout this entire process. I want to especially thank my housemates Sara Hoffman and Laurenellen McCann, who have sat and talked and laughed and cried and ate and drank with me from start to finish.