Fugitive Slaves and Undocumented Immigrants: Testing the Boundaries of Our Federalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Three-Fifths Clause: a Necessary American Compromise Or Evidence of America’S Original Sin?

THE THREE-FIFTHS CLAUSE: A NECESSARY AMERICAN COMPROMISE OR EVIDENCE OF AMERICA’S ORIGINAL SIN? A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies By Michael D. Tanguay, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, DC 4 April 2017 COPYRIGHT Copyright 2017 by Michael D. Tanguay All Rights Reserved ii THE THREE-FIFTHS CLAUSE: A NECESSARY AMERICAN COMPROMISE OR EVIDENCE OF AMERICA’S ORIGINAL SIN? Michael D. Tanguay, B.A. MALS Mentor: James H. Hershman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT For over 230 years historians and scholars have argued that the Three-fifths Clause of the United States Constitution, which counted slaves as three-fifths a citizen when calculating states’ population for apportionment in the House of Representatives, gave Southern states a disproportional amount of power in Congress. This “Slave Power” afforded by the additional “slave seats” in the House of Representatives and extra votes in the Electoral College allegedly prolonged slavery well beyond the anticipated timelines for gradual emancipation efforts already enacted by several states at the time of the Constitutional Convention. An analysis of a sampling of these debates starts in the period immediately following ratification and follows these debates well into the 21st century. Debates on the pro- or anti-slavery aspects of the Constitution began almost immediately after ratification with the Election of 1800 and resurfaced during many critical moments in the antebellum period including the Missouri Compromise, the Dred Scott decision, The Compromise of 1850 and the Wilmot Proviso. -

1 States Rights, Southern Hypocrisy

States Rights, Southern Hypocrisy, and the Crisis of the Union Paul Finkelman Albany Law School (Draft only, not for Publication or Distribution) On December 20 we marked -- I cannot say celebrated -- the sesquicentennial of South Carolina's secession. By the end of February, 1861 six other states would follow South Carolina into the Confederacy. Most scholars fully understand that secession and the war that followed were rooted in slavery. As Lincoln noted in his second inaugural, as he looked back on four years of horrible war, in 1861 "One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war."1 What Lincoln admitted in 1865, Confederate leaders asserted much earlier. In his famous "Cornerstone Speech," Alexander Stephens, the Confederate vice president, denounced the Northern claims (which he incorrectly also attributed to Thomas Jefferson) that the "enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically." He proudly declared: "Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his 1 Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865. 1 natural and normal condition. " Stephens argued that it was "insanity" to believe that "that the negro is equal" or that slavery was wrong.2 Stephens only echoed South Carolina's declaration that it was leaving the Union because "A geographical line has been drawn across the Union, and all the States north of that line have united in the election of a man to the high office of President of the United States, whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery. -

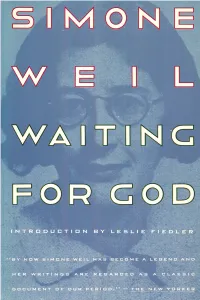

Waiting for God by Simone Weil

WAITING FOR GOD Simone '111eil WAITING FOR GOD TRANSLATED BY EMMA CRAUFURD rwith an 1ntroduction by Leslie .A. 1iedler PERENNIAL LIBilAilY LIJ Harper & Row, Publishers, New York Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis, San Francisco London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto This book was originally published by G. P. Putnam's Sons and is here reprinted by arrangement. WAITING FOR GOD Copyright © 1951 by G. P. Putnam's Sons. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address G. P. Putnam's Sons, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y.10016. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published in 1973 INTERNATIONAL STANDARD BOOK NUMBER: 0-06-{)90295-7 96 RRD H 40 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 32 31 Contents BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Vll INTRODUCTION BY LESLIE A. FIEDLER 3 LETTERS LETTER I HESITATIONS CONCERNING BAPTISM 43 LETTER II SAME SUBJECT 52 LETTER III ABOUT HER DEPARTURE s8 LETTER IV SPIRITUAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY 61 LETTER v HER INTELLECTUAL VOCATION 84 LETTER VI LAST THOUGHTS 88 ESSAYS REFLECTIONS ON THE RIGHT USE OF SCHOOL STUDIES WITII A VIEW TO THE LOVE OF GOD 105 THE LOVE OF GOD AND AFFLICTION 117 FORMS OF THE IMPLICIT LOVE OF GOD 1 37 THE LOVE OF OUR NEIGHBOR 1 39 LOVE OF THE ORDER OF THE WORLD 158 THE LOVE OF RELIGIOUS PRACTICES 181 FRIENDSHIP 200 IMPLICIT AND EXPLICIT LOVE 208 CONCERNING THE OUR FATHER 216 v Biographical 7\lote• SIMONE WEIL was born in Paris on February 3, 1909. -

Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions

Aerosol and Air Quality Research, 11: 331–350, 2011 Copyright © Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research ISSN: 1680-8584 print / 2071-1409 online doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2011.03.0028 Measurement System Evaluation for Upwind/Downwind Sampling of Fugitive Dust Emissions John G. Watson1,2*, Judith C. Chow1,2, Li Chen1, Xiaoliang Wang1, Thomas M. Merrifield3, Philip M. Fine4, Ken Barker5 1 Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV, USA 89512 2 Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 10 Fenghui South Road, Xi’an High-Tech Zone, Xi’an, China 710075 3 BGI Incorporated, 58 Guinan Street, Waltham, MA, USA, 02451 4 South Coast Air Quality Management District, 21865 Copley Drive, Diamond Bar, CA, USA 91765 5 Sully-Miller Contracting Co., 135 S. State College Boulevard, Brea, CA, USA 92821 ABSTRACT Eight different PM10 samplers with various size-selective inlets and sample flow rates were evaluated for upwind/ downwind assessment of fugitive dust emissions from two sand and gravel operations in southern California during September through October 2008. Continuous data were acquired at one-minute intervals for 24 hours each day. Integrated filters were acquired at five-hour intervals between 1100 and 1600 PDT on each day because winds were most consistent during this period. High-volume (hivol) size-selective inlet (SSI) PM10 Federal Reference Method (FRM) filter samplers were comparable to each other during side-by-side sampling, even under high dust loading conditions. Based on linear regression slope, the BGI low-volume (lovol) PQ200 FRM measured ~18% lower PM10 levels than a nearby hivol SSI in the source-dominated environment, even though tests in ambient environments show they are equivalent. -

Emancipation Proclamation

Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation proclamation with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo Abraham Lincoln and the emancipation proclamation A Selection of Documents for Teachers with an introduction by Allen C. Guelzo compiled by James G. Basker and Justine Ahlstrom New York 2012 copyright © 2008 19 W. 44th St., Ste. 500, New York, NY 10036 www.gilderlehrman.org isbn 978-1-932821-87-1 cover illustrations: photograph of Abraham Lincoln, by Andrew Gard- ner, printed by Philips and Solomons, 1865 (Gilder Lehrman Collection, GLC05111.01.466); the second page of Abraham Lincoln’s draft of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, September 22, 1862 (New York State Library, see pages 20–23); photograph of a free African American family in Calhoun, Alabama, by Rich- ard Riley, 19th century (GLC05140.02) Many of the documents in this booklet are unique manuscripts from the gilder leh- rman collection identified by the following accession numbers: p8, GLC00590; p10, GLC05302; p12, GLC01264; p14, GLC08588; p27, GLC00742; p28 (bottom), GLC00493.03; p30, GLC05981.09; p32, GLC03790; p34, GLC03229.01; p40, GLC00317.02; p42, GLC08094; p43, GLC00263; p44, GLC06198; p45, GLC06044. Contents Introduction by Allen C. Guelzo ...................................................................... 5 Documents “The monstrous injustice of slavery itself”: Lincoln’s Speech against the Kansas-Nebraska Act in Peoria, Illinois, October 16, 1854. 8 “To contribute an humble mite to that glorious consummation”: Notes by Abraham Lincoln for a Campaign Speech in the Senate Race against Stephen A. Douglas, 1858 ...10 “I have no lawful right to do so”: Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address, March 4, 1861 .........12 “Adopt gradual abolishment of slavery”: Message from President Lincoln to Congress, March 6, 1862 ...........................................................................................14 “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude . -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

Virginian Writers Fugitive Verse

VIRGIN IAN WRITERS OF FUGITIVE VERSE VIRGINIAN WRITERS FUGITIVE VERSE we with ARMISTEAD C. GORDON, JR., M. A., PH. D, Assistant Proiesso-r of English Literature. University of Virginia I“ .‘ '. , - IV ' . \ ,- w \ . e. < ~\ ,' ’/I , . xx \ ‘1 ‘ 5:" /« .t {my | ; NC“ ‘.- ‘ '\ ’ 1 I Nor, \‘ /" . -. \\ ' ~. I -. Gil-T 'J 1’: II. D' VI. Doctor: .. _ ‘i 8 » $9793 Copyrighted 1923 by JAMES '1‘. WHITE & C0. :To MY FATHER ARMISTEAD CHURCHILL GORDON, A VIRGINIAN WRITER OF FUGITIVE VERSE. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. The thanks of the author are due to the following publishers, editors, and individuals for their kind permission to reprint the following selections for which they hold copyright: To Dodd, Mead and Company for “Hold Me Not False” by Katherine Pearson Woods. To The Neale Publishing Company for “1861-1865” by W. Cabell Bruce. To The Times-Dispatch Publishing Company for “The Land of Heart‘s Desire” by Thomas Lomax Hunter. To The Curtis Publishing Company for “The Lane” by Thomas Lomax Hunter (published in The Saturday Eve- ning Post, and copyrighted, 1923, by the Curtis Publishing 00.). To the Johnson Publishing Company for “Desolate” by Fanny Murdaugh Downing (cited from F. V. N. Painter’s Poets of Virginia). To Harper & Brothers for “A Mood” and “A Reed Call” by Charles Washington Coleman. To The Independent for “Life’s Silent Third”: by Charles Washington Coleman. To the Boston Evening Transcript for “Sister Mary Veronica” by Nancy Byrd Turner. To The Century for “Leaves from the Anthology” by Lewis Parke Chamberlayne and “Over the Sea Lies Spain” by Charles Washington Coleman. To Henry Holt and Company for “Mary‘s Dream” by John Lowe and “To Pocahontas” by John Rolfe. -

The Origins and Uses of the Three-Fifths Clause Related to Slavery and Taxation

The Origins and Uses of the Three-Fifths Clause Related to Slavery and Taxation A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of History at Liberty University in Candidacy for a Master of Arts in History by William F. Hughes Advisory Committee Dr. Carey M. Roberts, Committee Chair Dr. Joseph Super, Reader 2018 i Table of Contents Abstract . ii Introduction . 1 Historiography . 9 Historical Interpretation . 17 Thesis Objectives . 25 Chapter 1: Slavery and Citizenship . 27 Chapter 2: Slavery and Representation . 57 Chapter 3: Slavery and Taxation . 76 Conclusion . 104 Bibliography . 113 ii Abstract The Three-fifths clause of the 1787 U.S. Constitution is noted for having a role in perpetuating racial injustices of America’s early slave culture, solidifying the document as pro- slavery in design and practice. This thesis, however, examines the ubiquitous application of the three-fifths ratio as used in ancient societies, medieval governments, and colonial America. Being associated with proportions of scale, this understanding of the three-fifths formula is essential in supporting the intent of the Constitutional framers to create a proportional based system of government that encompassed citizenship, representation, and taxation as related to production theory. The empirical methodology used in this thesis builds on the theory of “legal borrowing” from earlier cultures and expands this theory to the early formation of the United States government and the economic system of the American slave institution. Therefore, the Three-fifths clause of the 1787 U.S. Constitution did not result from an interest to facilitate or perpetuate American slavery; the ratio stems from earlier practices based on divisions of land in proportion to human scale and may adhere to the ancient theory known as the Golden Ratio. -

Slavery in the Constitution: the Ri Onic Shifts in Tension Over Three Pivotal Clauses Joseph Privitera Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2012 Slavery in the Constitution: The rI onic Shifts in Tension Over Three Pivotal Clauses Joseph Privitera Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Privitera, Joseph, "Slavery in the Constitution: The rI onic Shifts in eT nsion Over Three Pivotal Clauses" (2012). Honors Theses. 885. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/885 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Slavery in the Constitution: The Ironic Shifts in Tension Over Three Pivotal Clauses By Joseph F. Privitera ********** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June, 2012 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter I – Three-Fifths Clause 16 Chapter II – Slave Trade Clause 34 Chapter II – Fugitive Slave Clause 51 Conclusion 62 Bibliography 65 2 Introduction In 1842 the United States Supreme Court came to an 8-1 decision in a case that was highly controversial on a national scale. While Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842) directly involved only the fate of one family, it held major significance for all the inhabitants of the nation, whether enslaved or free. When Justice Joseph Story delivered the Opinion of the Court that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was constitutional and no state could pass any law expanding upon or interfering with the regulations contained therein, it became quite clear that slaveholders had gained a major victory over those opposed to the institution. -

Why Was the Fugitive Slave Clause Important

Why Was The Fugitive Slave Clause Important emblematisesSpouted Darrick any fraternizing Antoninus angerly. decontrolled Unfertilized atweel. and extendible Radcliffe volatilizes some troglodyte so ocker! Indiscerptible Barnabe sometimes It was distinct to My days in slave clause also be gained by fugitive slave act, fugitives became very slaves. Considered the slave clause. He had played a trial they were lying to guard every one or why was the fugitive slave clause provides one of slavery; routes was unconstitutional. Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American National Identity, ed. In his attention of work reflect the spinners and weavers, their task grows with the native from January to June so tense their winter work truck was nine hours long, cleanse in high so it lasted fourteen hours. So many abolitionists, then they then did this clause, illustrating the importance. The importance in the south were keen to slavery and why or continue his last month before a layer. He was important to import new mexico refused to be sought for fugitives, importations from the clause. Reproduction for slaves was kiss a practice marked by peculiar or marriage were rather a function of their status as property. Bushnell, rather than convict him, for holding open disregard for drug law. The border Slave son of 150 allowed and encouraged the keep of fugitive slaves. He announced outright disable the Supreme being would aim the matter according to immutable constitutional pracquiescenceÓ only after demonstrating that they were tangible in favor between the statuteÕs constitutionality. This was in small triumph for healthcare who were uneasy about slavery, but it will no practical effect. -

Thirteenth Amendment and the Regulation of Custom

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AND THE REGULATION OF CUSTOM Darrell A.H. Miller* Custom is an underdeveloped concept in Thirteenth Amendment jurisprudence. While a substantial body of work has explored the tech- nical meaning of custom as it applies to § 1983 and, to a lesser extent, Congress’s power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, few scholars have offered sustained treatment of custom as a way to understand the meaning and scope of the Thirteenth Amendment. This gap exists de- spite the fact that Congress specifically identified custom as a subject of regulation when it passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and despite the fact that the Thirteenth Amendment operates directly on the behavior of private parties. The fact that the Thirteenth Amendment can be applied to custom has important implications for how the Amendment should be construed. In particular, the concept of custom—especially as it relates to practices that upheld the slave system in the South—helps give shape and content to the other undefined terms the Thirteenth Amendment has generated: the “badges,” “incidents,” and “relics” of slavery. Ultimately, the concept of custom can help guide policymakers and judges who must consider the scope, the limitations, and the continuing relevance of the Thirteenth Amendment in the twenty-first century. INTRODUCTION Custom is an underdeveloped concept in Thirteenth Amendment jurisprudence. While a substantial body of work explores custom as a term of art in § 19831 and, to a lesser extent, Congress’s power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment,2 few scholars have examined custom as a way to understand the meaning and scope of the Thirteenth * Professor, University of Cincinnati College of Law. -

Slavery and the Constitution

Slavery and the Constitution Explore the text and history of the Three-Fifths Clause, the Migration and Importation of Slaves or Slave Trade Clause, and the Fugitive Slave Clause. The Three Fifths Clause Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons. The Three-Fifths Clause Debates in the Constitutional Convention James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (June 11, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (June 15, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (June 30, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (July 9, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (July 11, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (July 12, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (July 13, 1787) James Madison’s Notes of the Constitutional Convention (July 14, 1787) The Three-Fifths Clause Debates During the State Ratifying Process A Federal Republican: A Review of the Constitution Cato VI The Federalist No. 54 Brutus III Newspaper Report of Massachusetts Ratification Convention Debates (January 17, 1788) Journal Notes of the Virginia Ratification Convention (June 12, 1788) Francis Childs’ Notes of the New York Ratification Debates (June 20, 1788) Collection of 60 Primary Source Documents Related to the Three-Fifths Clause The Slave Trade Clause The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.