Anomalies in Linux Processor Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Review for Central Processing Unit Scheduling Algorithm

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 10, Issue 1, No 2, January 2013 ISSN (Print): 1694-0784 | ISSN (Online): 1694-0814 www.IJCSI.org 353 A Comprehensive Review for Central Processing Unit Scheduling Algorithm Ryan Richard Guadaña1, Maria Rona Perez2 and Larry Rutaquio Jr.3 1 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines 2 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines 3 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines Abstract when an attempt is made to execute a program, its This paper describe how does CPU facilitates tasks given by a admission to the set of currently executing processes is user through a Scheduling Algorithm. CPU carries out each either authorized or delayed by the long-term scheduler. instruction of the program in sequence then performs the basic Second is the Mid-term Scheduler that temporarily arithmetical, logical, and input/output operations of the system removes processes from main memory and places them on while a scheduling algorithm is used by the CPU to handle every process. The authors also tackled different scheduling disciplines secondary memory (such as a disk drive) or vice versa. and examples were provided in each algorithm in order to know Last is the Short Term Scheduler that decides which of the which algorithm is appropriate for various CPU goals. ready, in-memory processes are to be executed. Keywords: Kernel, Process State, Schedulers, Scheduling Algorithm, Utilization. 2. CPU Utilization 1. Introduction In order for a computer to be able to handle multiple applications simultaneously there must be an effective way The central processing unit (CPU) is a component of a of using the CPU. -

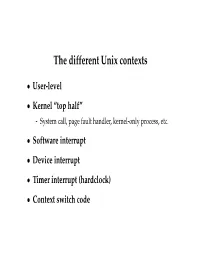

The Different Unix Contexts

The different Unix contexts • User-level • Kernel “top half” - System call, page fault handler, kernel-only process, etc. • Software interrupt • Device interrupt • Timer interrupt (hardclock) • Context switch code Transitions between contexts • User ! top half: syscall, page fault • User/top half ! device/timer interrupt: hardware • Top half ! user/context switch: return • Top half ! context switch: sleep • Context switch ! user/top half Top/bottom half synchronization • Top half kernel procedures can mask interrupts int x = splhigh (); /* ... */ splx (x); • splhigh disables all interrupts, but also splnet, splbio, splsoftnet, . • Masking interrupts in hardware can be expensive - Optimistic implementation – set mask flag on splhigh, check interrupted flag on splx Kernel Synchronization • Need to relinquish CPU when waiting for events - Disk read, network packet arrival, pipe write, signal, etc. • int tsleep(void *ident, int priority, ...); - Switches to another process - ident is arbitrary pointer—e.g., buffer address - priority is priority at which to run when woken up - PCATCH, if ORed into priority, means wake up on signal - Returns 0 if awakened, or ERESTART/EINTR on signal • int wakeup(void *ident); - Awakens all processes sleeping on ident - Restores SPL a time they went to sleep (so fine to sleep at splhigh) Process scheduling • Goal: High throughput - Minimize context switches to avoid wasting CPU, TLB misses, cache misses, even page faults. • Goal: Low latency - People typing at editors want fast response - Network services can be latency-bound, not CPU-bound • BSD time quantum: 1=10 sec (since ∼1980) - Empirically longest tolerable latency - Computers now faster, but job queues also shorter Scheduling algorithms • Round-robin • Priority scheduling • Shortest process next (if you can estimate it) • Fair-Share Schedule (try to be fair at level of users, not processes) Multilevel feeedback queues (BSD) • Every runnable proc. -

Go Forth with TTL !

Go Forth with TTL ! The Gigatron TTL Color Computer Forth for a Very Unusual Processor Ken Boak SV Fig. Forth Day 2019 . In September of 1975, MOS Technology launched the 6502 at the Wescon75 Computer Conference in San Francisco. Chuck Peddle and his team had created a very lean, stripped down, small die cpu. Costing just $25, the 6502 was a fraction of the cost of its nearest competitor. At that time the Intel 8080 was $360 and the Motorola 6800 was $175 . The 6502 was clearly a disruptive usurper. 25 year old, HP Engineer, Steve Wozniak, realised that this new microprocessor would be a game-changer and went on to incorporate it into the small computer he was developing. That machine went on to become the Apple I. In 1975 7400 TTL was the “Bread and Butter” of logic design: 7400 series TTL integrated circuits were developed in the early 1960’s. Initially quite expensive so mainly used in Military and Aerospace applications. By the early 1970’s TTL had become a versatile family of standardised, low cost,. easy to use logic. Typically about $1 per device. 7400 series logic was widely used in the design of minicomputers, including the PDP-11, the Data General Nova 1200 and later models of PDP-8. TTL was a viable, faster and cheaper processing solution than the emerging 8-bit microprocessors such as MOS 6502, Intel 8080 and the Motorola 6800. Essential Reading 16-bit TTL CPU board from Data General Nova 1200 The Gigatron TTL Computer – What is it? Started as a Hackaday.io project in Spring 2017 by Marcel van Kervinck of The Hague, Netherlands. -

Exploring Software Inefficiency With

ZeroSpy: Exploring Software Inefficiency with Redundant Zeros Xin You∗, Hailong Yang∗y, Zhongzhi Luan∗, Depei Qian∗ and Xu Liuz Beihang University, China∗, North Carolina State University, USAz State Key Laboratory of Mathematical Engineering and Advanced Computing, Wuxi, Chinay fyouxin2015,hailong.yang,07680,[email protected]∗, [email protected] Abstract—Redundant zeros cause inefficiencies in which the 1 for(int i=0;i<1000;++i) { 2 A[i] = 0; B[i] = i; zero values are loaded and computed repeatedly, resulting in 3 } 4 ... unnecessary memory traffic and identity computation that waste 5 for(int i=0;i<1000;++i) memory bandwidth and CPU resources. Optimizing compilers 6 I C[i] = A[i]-B[i]; is difficult in eliminating these zero-related inefficiencies due to Listing 1. An example code working on redundant zeros, where all variables are 32-bit integers. limitations in static analysis. Hardware approaches, in contrast, optimize inefficiencies without code modification, but are not enough to fulfill the computation, which yields better cache widely adopted in commodity processors. In this paper, we 1 propose ZeroSpy - a fine-grained profiler to identify redundant usage and vectorization potentials . zeros caused by both inappropriate use of data structures and Actually, a larger number of real-world applications (e.g., useless computation. ZeroSpy also provides intuitive optimization deep neural network and high-efficiency video coding) have guidance by revealing the locations where the redundant zeros already been reported to contain a significant amount of happen in source lines and calling contexts. The experimental redundant zeros and achieved significant speedup from the results demonstrate ZeroSpy is capable of identifying redundant zeros in programs that have been highly optimized for years. -

Comparing Systems Using Sample Data

Operating System and Process Monitoring Tools Arik Brooks, [email protected] Abstract: Monitoring the performance of operating systems and processes is essential to debug processes and systems, effectively manage system resources, making system decisions, and evaluating and examining systems. These tools are primarily divided into two main categories: real time and log-based. Real time monitoring tools are concerned with measuring the current system state and provide up to date information about the system performance. Log-based monitoring tools record system performance information for post-processing and analysis and to find trends in the system performance. This paper presents a survey of the most commonly used tools for monitoring operating system and process performance in Windows- and Unix-based systems and describes the unique challenges of real time and log-based performance monitoring. See Also: Table of Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Real Time Performance Monitoring Tools 2.1 Windows-Based Tools 2.1.1 Task Manager (taskmgr) 2.1.2 Performance Monitor (perfmon) 2.1.3 Process Monitor (pmon) 2.1.4 Process Explode (pview) 2.1.5 Process Viewer (pviewer) 2.2 Unix-Based Tools 2.2.1 Process Status (ps) 2.2.2 Top 2.2.3 Xosview 2.2.4 Treeps 2.3 Summary of Real Time Monitoring Tools 3. Log-Based Performance Monitoring Tools 3.1 Windows-Based Tools 3.1.1 Event Log Service and Event Viewer 3.1.2 Performance Logs and Alerts 3.1.3 Performance Data Log Service 3.2 Unix-Based Tools 3.2.1 System Activity Reporter (sar) 3.2.2 Cpustat 3.3 Summary of Log-Based Monitoring Tools 4. -

A Simple Chargeback System for SAS® Applications Running on UNIX and Linux Servers

SAS Global Forum 2007 Systems Architecture Paper: 194-2007 A Simple Chargeback System For SAS® Applications Running on UNIX and Linux Servers Michael A. Raithel, Westat, Rockville, MD Abstract Organizations that run SAS on UNIX and Linux servers often have a need to measure overall SAS usage and to charge the projects and users who utilize the servers. This allows an organization to pay for the hardware, software, and labor necessary to maintain and run these types of shared servers. However, performance management and accounting software is normally expensive. Purchasing such software, configuring it, and managing it may be prohibitive in terms of cost and in terms of having staff with the right skill sets to do so. Consequently, many organizations with UNIX or Linux servers do not have a reliable way to measure the overall use of SAS software and to charge individuals and projects for its use. This paper presents a simple methodology for creating a chargeback system on UNIX and Linux servers. It uses basic accounting programs found in the UNIX and Linux operating systems, and exploits them using SAS software. The paper presents an overview of the UNIX/Linux “sa” command and the basic accounting system. Then, it provides a SAS program that utilizes this command to capture and store monthly SAS usage statistics. The paper presents a second SAS program that reads the monthly SAS usage SAS data set and creates both a chargeback report and a general usage report. After reading this paper, you should be able to easily adapt the sample SAS programs to run on servers in your own environment. -

6502 Introduction

6502 Introduction Philipp Koehn 18 September 2019 Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 1 some history Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 1971 2 • First microprocessor on an integrated circuit: Intel 4004 • 4-bit central processing unit, 12 bit address space (4KB) Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 1975 3 • MOS Technology 6502 • Dominant CPU in home computers for a decade (Atari, Apple II, Nintendo Entertainment System, Commodore PET) Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 1977 4 • Atari 2600 • Video game console: Pong, Pac Man, ... connected to TV Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 1980 5 • Commodore VIC20 • 1 MHz, 5KB RAM, BASIC, 3.5KB RAM, 176x184 3 bit color video Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 1982 6 • Commodore C64 • 64KB RAM, 320x200 4 bit color video Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 Commodore C64 7 • BASIC programming language, but serious programs written in assembly • No fancy stuff like multi-process, user accounts, virtual memory, etc. • Machine itself had no mass storage - had to buy tape drive, then floppy disk drive, machine was obsolete once hard drives came around Philipp Koehn Computer Systems Fundamentals: 6502 Introduction 18 September 2019 BASIC Demo 8 • Commands get executed (just like Python interpreter) -

Download a Sample

Preface Like many American kids in 1979, I woke up to find that Santa had left a brand new Atari VCS1 under the tree (thanks, Mom and Dad, for paying Santa’s invoice!). This was a pretty big deal for a six- year-old who could tell you the location and manufacturer of every standup arcade cabinet within a five mile radius. Having an “arcade in your home” wasn’t just a thing you saw on Silver Spoons, it was now a real thing. The sights and sounds that jumped o↵ of our little Panasonic color TV probably deserve a gigantic run-on sentence worthy of Dylan Thomas, as my brother and I bounced tiny pixellated missiles o↵ of walls in Combat, combed through the perplexing game modes of Space Invaders, battled angry duck-like dragons in Adventure, and became Superman as we put flickering bad guys in a flickering jail. These cartridges were opaque obelisks packaged in boxes with fantastically unattainable illustrations, available at K-Mart for $30 or so. You could tell these species of video games weren’t related to arcade games, though they had a unique look-and-feel of their own. We also had an Apple ][ by this time, so I tried to fit all of these creatures into a digital taxonomy. Atari games had colors and fast motion, but not as much as arcade games, and they never were as complex as Apple ][ games. What made them tick? Why were Activision games so much more detailed? Would the missile still blow up your spaceship if you turned the TV o↵? (Turns out the answer is yes.) 1 It wasn’t sold as “Atari 2600” until 1982. -

The Ultimate C64 Overview Michael Steil, 25Th Chaos Communication Congress 2008

The Ultimate C64 Overview Michael Steil, http://www.pagetable.com/ 25th Chaos Communication Congress 2008 Retrocomputing is cool as never before. People play Look and Feel C64 games in emulators and listen to SID music, but few people know much about the C64 architecture A C64 only needs to be connected to power and a TV and its limitations, and what programming was like set (or monitor) to be fully functional. When turned back then. This paper attempts to give a comprehen- on, it shows a blue-on-blue theme with a startup mes- sive overview of the Commodore 64, including its in- sage and drops into a BASIC interpreter derived from ternals and quirks, making the point that classic Microsoft BASIC. In order to load and save BASIC computer systems aren't all that hard to understand - programs or use third party software, the C64 re- and that programmers today should be more aware of quires mass storage - either a “datasette” cassette the art that programming once used to be. tape drive or a disk drive like the 5.25" Commodore 1541. Commodore History Unless the user really wanted to interact with the BA- SIC interpreter, he would typically only use the BA- Commodore Business Machines was founded in 1962 SIC instructions LOAD, LIST and RUN in order to by Jack Tramiel. The company specialized on elec- access mass storage. LOAD"$",8 followed by LIST tronic calculators, and in 1976, Commodore bought shows the directory of the disk in the drive, and the chip manufacturer MOS Technology and decided LOAD"filename",8 followed by RUN would load and to have Chuck Peddle from MOS evolve their KIM-1 start a program. -

CS414 SP 2007 Assignment 1

CS414 SP 2007 Assignment 1 Due Feb. 07 at 11:59pm Submit your assignment using CMS 1. Which of the following should NOT be allowed in user mode? Briefly explain. a) Disable all interrupts. b) Read the time-of-day clock c) Set the time-of-day clock d) Perform a trap e) TSL (test-and-set instruction used for synchronization) Answer: (a), (c) should not be allowed. Which of the following components of a program state are shared across threads in a multi-threaded process ? Briefly explain. a) Register Values b) Heap memory c) Global variables d) Stack memory Answer: (b) and (c) are shared 2. After an interrupt occurs, hardware needs to save its current state (content of registers etc.) before starting the interrupt service routine. One issue is where to save this information. Here are two options: a) Put them in some special purpose internal registers which are exclusively used by interrupt service routine. b) Put them on the stack of the interrupted process. Briefly discuss the problems with above two options. Answer: (a) The problem is that second interrupt might occur while OS is in the middle of handling the first one. OS must prevent the second interrupt from overwriting the internal registers. This strategy leads to long dead times when interrupts are disabled and possibly lost interrupts and lost data. (b) The stack of the interrupted process might be a user stack. The stack pointer may not be legal which would cause a fatal error when the hardware tried to write some word at it. -

Cgroups Py: Using Linux Control Groups and Systemd to Manage CPU Time and Memory

cgroups py: Using Linux Control Groups and Systemd to Manage CPU Time and Memory Curtis Maves Jason St. John Research Computing Research Computing Purdue University Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana, USA West Lafayette, Indiana, USA [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—cgroups provide a mechanism to limit user and individual resource. 1 Each directory in a cgroupsfs hierarchy process resource consumption on Linux systems. This paper represents a cgroup. Subdirectories of a directory represent discusses cgroups py, a Python script that runs as a systemd child cgroups of a parent cgroup. Within each directory of service that dynamically throttles users on shared resource systems, such as HPC cluster front-ends. This is done using the the cgroups tree, various files are exposed that allow for cgroups kernel API and systemd. the control of the cgroup from userspace via writes, and the Index Terms—throttling, cgroups, systemd obtainment of statistics about the cgroup via reads [1]. B. Systemd and cgroups I. INTRODUCTION systemd A frequent problem on any shared resource with many users Systemd uses a named cgroup tree (called )—that is that a few users may over consume memory and CPU time. does not impose any resource limits—to manage processes When these resources are exhausted, other users have degraded because it provides a convenient way to organize processes in access to the system. A mechanism is needed to prevent this. a hierarchical structure. At the top of the hierarchy, systemd creates three cgroups By placing throttles on physical memory consumption and [2]: CPU time for each individual user, cgroups py prevents re- source exhaustion on a shared system and ensures continued • system.slice: This contains every non-user systemd access for other users. -

Linux CPU Schedulers: CFS and Muqss Comparison

Umeå University 2021-06-14 Bachelor’s Thesis In Computing Science Linux CPU Schedulers: CFS and MuQSS Comparison Name David Shakoori Gustafsson Supervisor Anna Jonsson Examinator Ola Ringdahl CFS and MuQSS Comparison Abstract The goal of this thesis is to compare two process schedulers for the Linux operating system. In order to provide a responsive and interactive user ex- perience, an efficient process scheduling algorithm is important. This thesis seeks to explain the potential performance differences by analysing the sched- ulers’ respective designs. The two schedulers that are tested and compared are Con Kolivas’s MuQSS and Linux’s default scheduler, CFS. They are tested with respect to three main aspects: latency, turn-around time and interactivity. Latency is tested by using benchmarking software, the turn- around time by timing software compilation, and interactivity by measuring video frame drop percentages under various background loads. These tests are performed on a desktop PC running Linux OpenSUSE Leap 15.2, using kernel version 5.11.18. The test results show that CFS manages to keep a generally lower latency, while turn-around times differs little between the two. Running the turn-around time test’s compilation using a single process gives MuQSS a small advantage, while dividing the compilation evenly among the available logical cores yields little difference. However, CFS clearly outper- forms MuQSS in the interactivity test, where it manages to keep frame drop percentages considerably lower under each tested background load. As is apparent by the results, Linux’s current default scheduler provides a more responsive and interactive experience within the testing conditions, than the alternative MuQSS.