Cgroups Py: Using Linux Control Groups and Systemd to Manage CPU Time and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comprehensive Review for Central Processing Unit Scheduling Algorithm

IJCSI International Journal of Computer Science Issues, Vol. 10, Issue 1, No 2, January 2013 ISSN (Print): 1694-0784 | ISSN (Online): 1694-0814 www.IJCSI.org 353 A Comprehensive Review for Central Processing Unit Scheduling Algorithm Ryan Richard Guadaña1, Maria Rona Perez2 and Larry Rutaquio Jr.3 1 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines 2 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines 3 Computer Studies and System Department, University of the East Caloocan City, 1400, Philippines Abstract when an attempt is made to execute a program, its This paper describe how does CPU facilitates tasks given by a admission to the set of currently executing processes is user through a Scheduling Algorithm. CPU carries out each either authorized or delayed by the long-term scheduler. instruction of the program in sequence then performs the basic Second is the Mid-term Scheduler that temporarily arithmetical, logical, and input/output operations of the system removes processes from main memory and places them on while a scheduling algorithm is used by the CPU to handle every process. The authors also tackled different scheduling disciplines secondary memory (such as a disk drive) or vice versa. and examples were provided in each algorithm in order to know Last is the Short Term Scheduler that decides which of the which algorithm is appropriate for various CPU goals. ready, in-memory processes are to be executed. Keywords: Kernel, Process State, Schedulers, Scheduling Algorithm, Utilization. 2. CPU Utilization 1. Introduction In order for a computer to be able to handle multiple applications simultaneously there must be an effective way The central processing unit (CPU) is a component of a of using the CPU. -

Security Assurance Requirements for Linux Application Container Deployments

NISTIR 8176 Security Assurance Requirements for Linux Application Container Deployments Ramaswamy Chandramouli This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8176 NISTIR 8176 Security Assurance Requirements for Linux Application Container Deployments Ramaswamy Chandramouli Computer Security Division Information Technology Laboratory This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8176 October 2017 U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Walter Copan, NIST Director and Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology NISTIR 8176 SECURITY ASSURANCE FOR LINUX CONTAINERS National Institute of Standards and Technology Internal Report 8176 37 pages (October 2017) This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.IR.8176 Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by NIST, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. This p There may be references in this publication to other publications currently under development by NIST in accordance with its assigned statutory responsibilities. The information in this publication, including concepts and methodologies, may be used by federal agencies even before the completion of such companion publications. Thus, until each ublication is available free of charge from: http publication is completed, current requirements, guidelines, and procedures, where they exist, remain operative. For planning and transition purposes, federal agencies may wish to closely follow the development of these new publications by NIST. -

The Different Unix Contexts

The different Unix contexts • User-level • Kernel “top half” - System call, page fault handler, kernel-only process, etc. • Software interrupt • Device interrupt • Timer interrupt (hardclock) • Context switch code Transitions between contexts • User ! top half: syscall, page fault • User/top half ! device/timer interrupt: hardware • Top half ! user/context switch: return • Top half ! context switch: sleep • Context switch ! user/top half Top/bottom half synchronization • Top half kernel procedures can mask interrupts int x = splhigh (); /* ... */ splx (x); • splhigh disables all interrupts, but also splnet, splbio, splsoftnet, . • Masking interrupts in hardware can be expensive - Optimistic implementation – set mask flag on splhigh, check interrupted flag on splx Kernel Synchronization • Need to relinquish CPU when waiting for events - Disk read, network packet arrival, pipe write, signal, etc. • int tsleep(void *ident, int priority, ...); - Switches to another process - ident is arbitrary pointer—e.g., buffer address - priority is priority at which to run when woken up - PCATCH, if ORed into priority, means wake up on signal - Returns 0 if awakened, or ERESTART/EINTR on signal • int wakeup(void *ident); - Awakens all processes sleeping on ident - Restores SPL a time they went to sleep (so fine to sleep at splhigh) Process scheduling • Goal: High throughput - Minimize context switches to avoid wasting CPU, TLB misses, cache misses, even page faults. • Goal: Low latency - People typing at editors want fast response - Network services can be latency-bound, not CPU-bound • BSD time quantum: 1=10 sec (since ∼1980) - Empirically longest tolerable latency - Computers now faster, but job queues also shorter Scheduling algorithms • Round-robin • Priority scheduling • Shortest process next (if you can estimate it) • Fair-Share Schedule (try to be fair at level of users, not processes) Multilevel feeedback queues (BSD) • Every runnable proc. -

Multicore Operating-System Support for Mixed Criticality∗

Multicore Operating-System Support for Mixed Criticality∗ James H. Anderson, Sanjoy K. Baruah, and Bjorn¨ B. Brandenburg The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Abstract Different criticality levels provide different levels of assurance against failure. In current avionics designs, Ongoing research is discussed on the development of highly-critical software is kept physically separate from operating-system support for enabling mixed-criticality less-critical software. Moreover, no currently deployed air- workloads to be supported on multicore platforms. This craft uses multicore processors to host highly-critical tasks work is motivated by avionics systems in which such work- (more precisely, if multicore processors are used, and if loads occur. In the mixed-criticality workload model that is such a processor hosts highly-critical applications, then all considered, task execution costs may be determined using but one of its cores are turned off). These design decisions more-stringent methods at high criticality levels, and less- are largely driven by certification issues. For example, cer- stringent methods at low criticality levels. The main focus tifying highly-critical components becomes easier if poten- of this research effort is devising mechanisms for providing tially adverse interactions among components executing on “temporal isolation” across criticality levels: lower levels different cores through shared hardware such as caches are should not adversely “interfere” with higher levels. simply “defined” not to occur. Unfortunately, hosting an overall workload as described here clearly wastes process- ing resources. 1 Introduction In this paper, we propose operating-system infrastruc- ture that allows applications of different criticalities to be The evolution of computational frameworks for avionics co-hosted on a multicore platform. -

Comparing Systems Using Sample Data

Operating System and Process Monitoring Tools Arik Brooks, [email protected] Abstract: Monitoring the performance of operating systems and processes is essential to debug processes and systems, effectively manage system resources, making system decisions, and evaluating and examining systems. These tools are primarily divided into two main categories: real time and log-based. Real time monitoring tools are concerned with measuring the current system state and provide up to date information about the system performance. Log-based monitoring tools record system performance information for post-processing and analysis and to find trends in the system performance. This paper presents a survey of the most commonly used tools for monitoring operating system and process performance in Windows- and Unix-based systems and describes the unique challenges of real time and log-based performance monitoring. See Also: Table of Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Real Time Performance Monitoring Tools 2.1 Windows-Based Tools 2.1.1 Task Manager (taskmgr) 2.1.2 Performance Monitor (perfmon) 2.1.3 Process Monitor (pmon) 2.1.4 Process Explode (pview) 2.1.5 Process Viewer (pviewer) 2.2 Unix-Based Tools 2.2.1 Process Status (ps) 2.2.2 Top 2.2.3 Xosview 2.2.4 Treeps 2.3 Summary of Real Time Monitoring Tools 3. Log-Based Performance Monitoring Tools 3.1 Windows-Based Tools 3.1.1 Event Log Service and Event Viewer 3.1.2 Performance Logs and Alerts 3.1.3 Performance Data Log Service 3.2 Unix-Based Tools 3.2.1 System Activity Reporter (sar) 3.2.2 Cpustat 3.3 Summary of Log-Based Monitoring Tools 4. -

A Simple Chargeback System for SAS® Applications Running on UNIX and Linux Servers

SAS Global Forum 2007 Systems Architecture Paper: 194-2007 A Simple Chargeback System For SAS® Applications Running on UNIX and Linux Servers Michael A. Raithel, Westat, Rockville, MD Abstract Organizations that run SAS on UNIX and Linux servers often have a need to measure overall SAS usage and to charge the projects and users who utilize the servers. This allows an organization to pay for the hardware, software, and labor necessary to maintain and run these types of shared servers. However, performance management and accounting software is normally expensive. Purchasing such software, configuring it, and managing it may be prohibitive in terms of cost and in terms of having staff with the right skill sets to do so. Consequently, many organizations with UNIX or Linux servers do not have a reliable way to measure the overall use of SAS software and to charge individuals and projects for its use. This paper presents a simple methodology for creating a chargeback system on UNIX and Linux servers. It uses basic accounting programs found in the UNIX and Linux operating systems, and exploits them using SAS software. The paper presents an overview of the UNIX/Linux “sa” command and the basic accounting system. Then, it provides a SAS program that utilizes this command to capture and store monthly SAS usage statistics. The paper presents a second SAS program that reads the monthly SAS usage SAS data set and creates both a chargeback report and a general usage report. After reading this paper, you should be able to easily adapt the sample SAS programs to run on servers in your own environment. -

Container and Kernel-Based Virtual Machine (KVM) Virtualization for Network Function Virtualization (NFV)

Container and Kernel-Based Virtual Machine (KVM) Virtualization for Network Function Virtualization (NFV) White Paper August 2015 Order Number: 332860-001US YouLegal Lines andmay Disclaimers not use or facilitate the use of this document in connection with any infringement or other legal analysis concerning Intel products described herein. You agree to grant Intel a non-exclusive, royalty-free license to any patent claim thereafter drafted which includes subject matter disclosed herein. No license (express or implied, by estoppel or otherwise) to any intellectual property rights is granted by this document. All information provided here is subject to change without notice. Contact your Intel representative to obtain the latest Intel product specifications and roadmaps. The products described may contain design defects or errors known as errata which may cause the product to deviate from published specifications. Current characterized errata are available on request. Copies of documents which have an order number and are referenced in this document may be obtained by calling 1-800-548-4725 or by visiting: http://www.intel.com/ design/literature.htm. Intel technologies’ features and benefits depend on system configuration and may require enabled hardware, software or service activation. Learn more at http:// www.intel.com/ or from the OEM or retailer. Results have been estimated or simulated using internal Intel analysis or architecture simulation or modeling, and provided to you for informational purposes. Any differences in your system hardware, software or configuration may affect your actual performance. For more complete information about performance and benchmark results, visit www.intel.com/benchmarks. Tests document performance of components on a particular test, in specific systems. -

Containerization Introduction to Containers, Docker and Kubernetes

Containerization Introduction to Containers, Docker and Kubernetes EECS 768 Apoorv Ingle [email protected] Containers • Containers – lightweight VM or chroot on steroids • Feels like a virtual machine • Get a shell • Install packages • Run applications • Run services • But not really • Uses host kernel • Cannot boot OS • Does not need PID 1 • Process visible to host machine Containers • VM vs Containers Containers • Container Anatomy • cgroup: limit the use of resources • namespace: limit what processes can see (hence use) Containers • cgroup • Resource metering and limiting • CPU • IO • Network • etc.. • $ ls /sys/fs/cgroup Containers • Separate Hierarchies for each resource subsystem (CPU, IO, etc.) • Each process belongs to exactly 1 node • Node is a group of processes • Share resource Containers • CPU cgroup • Keeps track • user/system CPU • Usage per CPU • Can set weights • CPUset cgroup • Reserve to CPU to specific applications • Avoids context switch overheads • Useful for non uniform memory access (NUMA) Containers • Memory cgroup • Tracks pages used by each group • Pages can be shared across groups • Pages “charged” to a group • Shared pages “split the cost” • Set limits on usage Containers • Namespaces • Provides a view of the system to process • Controls what a process can see • Multiple namespaces • pid • net • mnt • uts • ipc • usr Containers • PID namespace • Processes within a PID namespace see only process in the same namespace • Each PID namespace has its own numbering staring from 1 • Namespace is killed when PID 1 goes away -

CS414 SP 2007 Assignment 1

CS414 SP 2007 Assignment 1 Due Feb. 07 at 11:59pm Submit your assignment using CMS 1. Which of the following should NOT be allowed in user mode? Briefly explain. a) Disable all interrupts. b) Read the time-of-day clock c) Set the time-of-day clock d) Perform a trap e) TSL (test-and-set instruction used for synchronization) Answer: (a), (c) should not be allowed. Which of the following components of a program state are shared across threads in a multi-threaded process ? Briefly explain. a) Register Values b) Heap memory c) Global variables d) Stack memory Answer: (b) and (c) are shared 2. After an interrupt occurs, hardware needs to save its current state (content of registers etc.) before starting the interrupt service routine. One issue is where to save this information. Here are two options: a) Put them in some special purpose internal registers which are exclusively used by interrupt service routine. b) Put them on the stack of the interrupted process. Briefly discuss the problems with above two options. Answer: (a) The problem is that second interrupt might occur while OS is in the middle of handling the first one. OS must prevent the second interrupt from overwriting the internal registers. This strategy leads to long dead times when interrupts are disabled and possibly lost interrupts and lost data. (b) The stack of the interrupted process might be a user stack. The stack pointer may not be legal which would cause a fatal error when the hardware tried to write some word at it. -

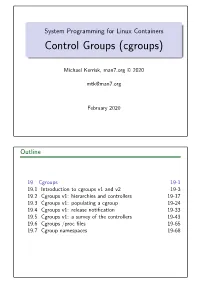

Control Groups (Cgroups)

System Programming for Linux Containers Control Groups (cgroups) Michael Kerrisk, man7.org © 2020 [email protected] February 2020 Outline 19 Cgroups 19-1 19.1 Introduction to cgroups v1 and v2 19-3 19.2 Cgroups v1: hierarchies and controllers 19-17 19.3 Cgroups v1: populating a cgroup 19-24 19.4 Cgroups v1: release notification 19-33 19.5 Cgroups v1: a survey of the controllers 19-43 19.6 Cgroups /procfiles 19-65 19.7 Cgroup namespaces 19-68 Outline 19 Cgroups 19-1 19.1 Introduction to cgroups v1 and v2 19-3 19.2 Cgroups v1: hierarchies and controllers 19-17 19.3 Cgroups v1: populating a cgroup 19-24 19.4 Cgroups v1: release notification 19-33 19.5 Cgroups v1: a survey of the controllers 19-43 19.6 Cgroups /procfiles 19-65 19.7 Cgroup namespaces 19-68 Goals Cgroups is a big topic Many controllers V1 versus V2 interfaces Our goal: understand fundamental semantics of cgroup filesystem and interfaces Useful from a programming perspective How do I build container frameworks? What else can I build with cgroups? And useful from a system engineering perspective What’s going on underneath my container’s hood? System Programming for Linux Containers ©2020, Michael Kerrisk Cgroups 19-4 §19.1 Focus We’ll focus on: General principles of operation; goals of cgroups The cgroup filesystem Interacting with the cgroup filesystem using shell commands Problems with cgroups v1, motivations for cgroups v2 Differences between cgroups v1 and v2 We’ll look briefly at some of the controllers System Programming for Linux Containers ©2020, Michael Kerrisk Cgroups 19-5 §19.1 -

A Container-Based Approach to OS Specialization for Exascale Computing

A Container-Based Approach to OS Specialization for Exascale Computing Judicael A. Zounmevo∗, Swann Perarnau∗, Kamil Iskra∗, Kazutomo Yoshii∗, Roberto Gioiosay, Brian C. Van Essenz, Maya B. Gokhalez, Edgar A. Leonz ∗Argonne National Laboratory fjzounmevo@, perarnau@mcs., iskra@mcs., [email protected] yPacific Northwest National Laboratory. [email protected] zLawrence Livermore National Laboratory. fvanessen1, maya, [email protected] Abstract—Future exascale systems will impose several con- view is essential for scalability, enabling compute nodes to flicting challenges on the operating system (OS) running on manage and optimize massive intranode thread and task par- the compute nodes of such machines. On the one hand, the allelism and adapt to new memory technologies. In addition, targeted extreme scale requires the kind of high resource usage efficiency that is best provided by lightweight OSes. At the Argo introduces the idea of “enclaves,” a set of resources same time, substantial changes in hardware are expected for dedicated to a particular service and capable of introspection exascale systems. Compute nodes are expected to host a mix of and autonomic response. Enclaves will be able to change the general-purpose and special-purpose processors or accelerators system configuration of nodes and the allocation of power tailored for serial, parallel, compute-intensive, or I/O-intensive to different nodes or to migrate data or computations from workloads. Similarly, the deeper and more complex memory hierarchy will expose multiple coherence domains and NUMA one node to another. They will be used to demonstrate nodes in addition to incorporating nonvolatile RAM. That the support of different levels of fault tolerance—a key expected workload and hardware heterogeneity and complexity concern of exascale systems—with some enclaves handling is not compatible with the simplicity that characterizes high node failures by means of global restart and other enclaves performance lightweight kernels. -

Linux CPU Schedulers: CFS and Muqss Comparison

Umeå University 2021-06-14 Bachelor’s Thesis In Computing Science Linux CPU Schedulers: CFS and MuQSS Comparison Name David Shakoori Gustafsson Supervisor Anna Jonsson Examinator Ola Ringdahl CFS and MuQSS Comparison Abstract The goal of this thesis is to compare two process schedulers for the Linux operating system. In order to provide a responsive and interactive user ex- perience, an efficient process scheduling algorithm is important. This thesis seeks to explain the potential performance differences by analysing the sched- ulers’ respective designs. The two schedulers that are tested and compared are Con Kolivas’s MuQSS and Linux’s default scheduler, CFS. They are tested with respect to three main aspects: latency, turn-around time and interactivity. Latency is tested by using benchmarking software, the turn- around time by timing software compilation, and interactivity by measuring video frame drop percentages under various background loads. These tests are performed on a desktop PC running Linux OpenSUSE Leap 15.2, using kernel version 5.11.18. The test results show that CFS manages to keep a generally lower latency, while turn-around times differs little between the two. Running the turn-around time test’s compilation using a single process gives MuQSS a small advantage, while dividing the compilation evenly among the available logical cores yields little difference. However, CFS clearly outper- forms MuQSS in the interactivity test, where it manages to keep frame drop percentages considerably lower under each tested background load. As is apparent by the results, Linux’s current default scheduler provides a more responsive and interactive experience within the testing conditions, than the alternative MuQSS.