557 Bound Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence

Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence Jon Woronoff, Series Editor 1. British Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2005. 2. United States Intelligence, by Michael A. Turner, 2006. 3. Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. 4. International Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2006. 5. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. 6. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. 7. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. 8. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. 9. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Historical Dictionary of Air Intelligence Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 9 The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham, Maryland • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Published in the United States of America by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road Plymouth PL6 7PY United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Trenear-Harvey, Glenmore S., 1940– Historical dictionary of air intelligence / Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey. p. cm. — (Historical dictionaries of intelligence and counterintelligence ; no. 9) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-5982-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8108-5982-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8108-6294-4 (eBook) ISBN-10: 0-8108-6294-8 (eBook) 1. -

The Great Game in Space China’S Evolving ASAT Weapons Programs and Their Implications for Future U.S

The Great Game in Space China’s Evolving ASAT Weapons Programs and Their Implications for Future U.S. Strategy Ian Easton The Project 2049 Institute seeks If there is a great power war in this century, it will not begin to guide decision makers toward with the sound of explosions on the ground and in the sky, but a more secure Asia by the rather with the bursting of kinetic energy and the flashing of century’s mid-point. The laser light in the silence of outer space. China is engaged in an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons drive that has profound organization fills a gap in the implications for future U.S. military strategy in the Pacific. This public policy realm through Chinese ASAT build-up, notable for its assertive testing regime forward-looking, region-specific and unexpectedly rapid development as well as its broad scale, research on alternative security has already triggered a cascade of events in terms of U.S. and policy solutions. Its strategic recalibration and weapons acquisition plans. The interdisciplinary approach draws notion that the U.S. could be caught off-guard in a “space on rigorous analysis of Pearl Harbor” and quickly reduced from an information-age socioeconomic, governance, military juggernaut into a disadvantaged industrial-age power in any conflict with China is being taken very seriously military, environmental, by U.S. war planners. As a result, while China’s already technological and political impressive ASAT program continues to mature and expand, trends, and input from key the U.S. is evolving its own counter-ASAT deterrent as well as players in the region, with an eye its next generation space technology to meet the challenge, toward educating the public and and this is leading to a “great game” style competition in informing policy debate. -

The Scribes Journal of Legal Writing

THE SCRIBES JOURNAL OF LEGAL WRITING Founding Editor: Bryan A. Garner Editor in Chief Joseph Kimble Thomas Cooley Law School Lansing, Michigan Associate Editor Associate Editor David W. Schultz Mark Cooney Jones McClure Publishing, Inc. Thomas Cooley Law School Houston, Texas Lansing, Michigan Copyeditor Karen Magnuson AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF SCRIBES — THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF LEGAL WRITERS Subscription orders should be sent to the Executive Director of Scribes, Professor Norman E. Plate, Thomas Cooley Law School, PO Box 13038, Lansing, Michigan 48901. Articles, essays, notes, correspondence, and books for review should be sent to Joseph Kimble at the same address. ©2010 by Scribes. All rights reserved. ISSN 1049–5177 From the Editor You’re holding a one-of-a-kind volume — transcripts of Bryan Garner’s interviews with Supreme Court Justices on legal writing and advocacy. These pages contain a rich lode of quotable nuggets. While read- ing, I started to jot down some examples and wound up with three dozen. Here is just a small sampling: • “I have yet to put down a brief and say, ‘I wish that had been longer’” (p. 35). • “What the academy is doing, as far as I can tell, is largely of no use or interest to people who actually practice law” (p. 37). • “I love But at the beginning of a sentence . .” (p. 60). • “[G]ood counsel welcomes, welcomes questions” (p. 70). • “So the crafting of that issue . Man, that’s everything. The rest is background music” (p. 75). • “[T]he genius is having a ten-dollar idea in a five-cent sentence, not having a five-cent idea in a ten-dollar sentence” (p. -

The Physics of Space Security a Reference Manual

THE PHYSICS The Physics of OF S P Space Security ACE SECURITY A Reference Manual David Wright, Laura Grego, and Lisbeth Gronlund WRIGHT , GREGO , AND GRONLUND RECONSIDERING THE RULES OF SPACE PROJECT RECONSIDERING THE RULES OF SPACE PROJECT 222671 00i-088_Front Matter.qxd 9/21/12 9:48 AM Page ii 222671 00i-088_Front Matter.qxd 9/21/12 9:48 AM Page iii The Physics of Space Security a reference manual David Wright, Laura Grego, and Lisbeth Gronlund 222671 00i-088_Front Matter.qxd 9/21/12 9:48 AM Page iv © 2005 by David Wright, Laura Grego, and Lisbeth Gronlund All rights reserved. ISBN#: 0-87724-047-7 The views expressed in this volume are those held by each contributor and are not necessarily those of the Officers and Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Please direct inquiries to: American Academy of Arts and Sciences 136 Irving Street Cambridge, MA 02138-1996 Telephone: (617) 576-5000 Fax: (617) 576-5050 Email: [email protected] Visit our website at www.amacad.org or Union of Concerned Scientists Two Brattle Square Cambridge, MA 02138-3780 Telephone: (617) 547-5552 Fax: (617) 864-9405 www.ucsusa.org Cover photo: Space Station over the Ionian Sea © NASA 222671 00i-088_Front Matter.qxd 9/21/12 9:48 AM Page v Contents xi PREFACE 1 SECTION 1 Introduction 5 SECTION 2 Policy-Relevant Implications 13 SECTION 3 Technical Implications and General Conclusions 19 SECTION 4 The Basics of Satellite Orbits 29 SECTION 5 Types of Orbits, or Why Satellites Are Where They Are 49 SECTION 6 Maneuvering in Space 69 SECTION 7 Implications of -

View Creditor's List

YELLOW ROSE AAA SLING & INDUSTRIAL ACCESS TRANSLATION 322 WEST CLEVELAND RD 425 36TH STREET SW 1453 WOODGATE WAY GRANGER IN 46530-7003a GRAND RAPIDS MI 49548-2108 TALLAHASSEE FL 32312 1-800-CONFERENCE(R) AAA WIRE ROPE & SPLICING ACCESSINDIANA/CIVICNET P. O. BOX 8103 12650 SIBLEY ROAD 10 WEST MARKET STREET AURORA IL 60507-8103 RIVERVIEW MI 48192 SUITE 600 INDIANAPOLIS IN 46204 3 COM CORPORATION AAYS RENT-ALL COMPANY 5400 BAYFRONT PLAZA INCORPORATED ACCRALINE INCORPORATED SANTA CA 95052-8145 811 W. EDISON 1420 WEST BIKE STREET MISHAWAKA IN 46545 BREMEN IN 46506 3M- AUTOMOTIVE DIVISION 3M CENTER BUILDING 0207-01- ABAD EDGAR ACCUBILT INC. W-21 51127 CROOKED OAK DRIVE 2365 RESEARCH DRIVE ST. PAUL MN 55144-1000 GRANGER IN 46530 JACKSON MI 49203 A & A MANUFACTURING ABANAKI CORPORATION ACCU-FLO INCORPORATED COMPANY INCORPORATED 17387 MUNN ROAD 21380 COOLIDGE HIGHWAY 2300 SOUTH CALHOUN ROAD CHAGRIN FALLS OH 44023 OAK PARK MI 48237 NEW BERLIN WI 53151-0847 ABB FLEXIBLE AUTOMATION ACCURATE BORING A & B MACHINING 2487 SOUTH COMMERCE COMPANY INC. 5677 AIRLINE RD DRIVE 17420 MALYN ROAD FRUITPORT MI 49415 NEW BERLIN WI 53151-2717 FRASER MI 48026 A & S FULL SERVICE ABF FREIGHT SYSTEM ACCURATE MEASUREMENT ELECTRIC INC INCORPORATED SYSTEMS P.O BOX 395 813 WEST SAMPLE STREET 2360 NORTH LINDBERGH GRANGER IN 46530 SOUTH BEND IN 46601-1418 BLVD. ST. LOUIS MO 63114 A T & T ABIGT JOHN P. O. BOX 5080 1210 S. TWYCKENHAM DRIVE ACCURATE WELDING CAROL STREAM IL 60197-5080 SOUTH BEND IN 46615 3700 BUFFALO ROAD NILES MI 49120 A. RUITER LTD ABIGT JOHN D. -

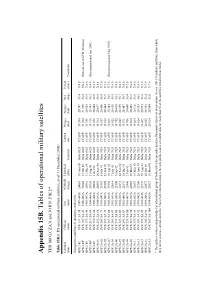

Appendix 15B. Tables of Operational Military Satellites TED MOLCZAN and JOHN PIKE*

Appendix 15B. Tables of operational military satellites TED MOLCZAN and JOHN PIKE* Table 15B.1. US operational military satellites, as of 31 December 2002a Common Official Intl NORAD Launched Launch Perigee Apogee Incl. Period name name name design. (date) Launcher site (km) (km) (deg.) (min.) Comments Navigation satellites in medium earth orbit GPS 2-02 SVN 13/USA 38 1989-044A 20061 10 June 89 Delta 6925 CCAFS 19 594 20 787 53.4 718.0 GPS 2-04b SVN 19/USA 47 1989-085A 20302 21 Oct 89 Delta 6925 CCAFS 21 204 21 238 53.4 760.2 (Retired, not in SEM Almanac) GPS 2-05 SVN 17/USA 49 1989-097A 20361 11 Dec 89 Delta 6925 CCAFS 19 795 20 583 55.9 718.0 GPS 2-08b SVN 21/USA 63 1990-068A 20724 2 Aug 90 Delta 6925 CCAFS 19 716 20 705 56.2 718.8 (Decommissioned Jan. 2003) GPS 2-09 SVN 15/USA 64 1990-088A 20830 1 Oct 90 Delta 6925 CCAFS 19 978 20 404 55.8 718.0 GPS 2A-01 SVN 23/USA 66 1990-103A 20959 26 Nov 90 Delta 6925 CCAFS 19 764 20 637 56.4 718.4 GPS 2A-02 SVN 24/USA 71 1991-047A 21552 4 July 91 Delta 7925 CCAFS 19 927 20 450 56.0 717.9 GPS 2A-03 SVN 25/USA 79 1992-009A 21890 23 Feb 92 Delta 7925 CCAFS 19 913 20 464 53.9 717.9 GPS 2A-04b SVN 28/USA 80 1992-019A 21930 10 Apr 92 Delta 7925 CCAFS 20 088 20 284 54.5 717.8 (Decommissioned May 1997) GPS 2A-05 SVN 26/USA 83 1992-039A 22014 7 July 92 Delta 7925 CCAFS 19 822 20 558 55.9 718.0 GPS 2A-06 SVN 27/USA 84 1992-058A 22108 9 Sep 92 Delta 7925 CCAFS 19 742 20 638 54.1 718.0 GPS 2A-07 SVN 32/USA 85 1992-079A 22231 22 Nov 92 Delta 7925 CCAFS 20 042 20 339 55.7 718.0 GPS 2A-08 SVN 29/USA 87 1992-089A -

China Dream, Space Dream: China's Progress in Space Technologies and Implications for the United States

China Dream, Space Dream 中国梦,航天梦China’s Progress in Space Technologies and Implications for the United States A report prepared for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Kevin Pollpeter Eric Anderson Jordan Wilson Fan Yang Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Dr. Patrick Besha and Dr. Scott Pace for reviewing a previous draft of this report. They would also like to thank Lynne Bush and Bret Silvis for their master editing skills. Of course, any errors or omissions are the fault of authors. Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 108-7. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. CONTENTS Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................... i Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 -

Space Security 2010

SPACE SECURITY 2010 spacesecurity.org SPACE 2010SECURITY SPACESECURITY.ORG iii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publications Data Space Security 2010 ISBN : 978-1-895722-78-9 © 2010 SPACESECURITY.ORG Edited by Cesar Jaramillo Design and layout: Creative Services, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Cover image: Artist rendition of the February 2009 satellite collision between Cosmos 2251 and Iridium 33. Artwork courtesy of Phil Smith. Printed in Canada Printer: Pandora Press, Kitchener, Ontario First published August 2010 Please direct inquires to: Cesar Jaramillo Project Ploughshares 57 Erb Street West Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2 Canada Telephone: 519-888-6541, ext. 708 Fax: 519-888-0018 Email: [email protected] iv Governance Group Cesar Jaramillo Managing Editor, Project Ploughshares Phillip Baines Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Canada Dr. Ram Jakhu Institute of Air and Space Law, McGill University John Siebert Project Ploughshares Dr. Jennifer Simons The Simons Foundation Dr. Ray Williamson Secure World Foundation Advisory Board Hon. Philip E. Coyle III Center for Defense Information Richard DalBello Intelsat General Corporation Theresa Hitchens United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Dr. John Logsdon The George Washington University (Prof. emeritus) Dr. Lucy Stojak HEC Montréal/International Space University v Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 Acronyms PAGE 7 Introduction PAGE 11 Acknowledgements PAGE 13 Executive Summary PAGE 29 Chapter 1 – The Space Environment: -

June 2021 ITG Journal

International Trumpet Guild® Journal to promote communications among trumpet players around the world and to improve the artistic level of performance, teaching, and literature associated with the trumpet June 2021 ITG Journal The International Trumpet Guild® (ITG) is the copyright owner of all data contained in this file. ITG gives the individual end-user the right to: • Download and retain an electronic copy of this file on electronic devices for the sole use of the end-user • Print a single copy of this file • Quote fair-use passages of this file in not-for-profit research papers as long as the ITG Journal, date, and page number are cited as the source. The International Trumpet Guild®, under the umbrella of United States and international copyright laws, prohibits the following without prior writ ten permission from the Publications Editor of the ITG: • Duplication or distribution of this file or its contents in any manner that does not conform with the uses as stated above • Alteration of this file or the data contained herein • Placement of this file on any web site, server, or any other database or device that allows for the accessing or copying of this file or the data contained herein by any party, including such a device intended to be used wholly within an institution. By scrolling past this page you agree to the fair use guidelines stated above. http://www.trumpetguild.org This cover sheet must accompany this file. The removal of this information is strictly prohibited and can result in expulsion from the organization and legal action. -

Type Category Description F Food and Beverage

The original source for data in this spreadsheet is a 2002 study for MassDEP by Draper/Lennon, Inc. titled Identification, Characterization, and Mapping of Food Waste and Food Waste Generators in Massachusetts . The final report from this study is available online at: http://www.mass.gov/dep/about/priorities/foodwast.doc. The data was updated in summer 2011 by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 1 office. This study identified large generators of food waste in Massachusetts, such as food processors, wholesalers, grocery stores, institutions, and large restaurants. It calculated estimated food waste generation, shown in tons per year (TPY) in column G, and mapped generator locations to facilitate planning of programs and facilities for capturing source separated organic materials for composting or other diversion. Note that waste generation estimates are not available for food and beverage manufacturers/processors and distributors due to the variability in these sectors. In some other cases, generation estimates are not available for other facilities when data needed to estimate generation is missing for that location. Facility Category Codes in column F marked TYPE show generator groupings in the report as follows: Type Category Description Food and Beverage F Manufacturers/Processors W Wholesale Distributors IH Institutions -Healthcare Facilities IS Institutions -Independent Schools IC Institutions -Colleges/Universities IP Institutions -Correctional Facilities C Resorts and Conference Facilities G Supermarkets and Grocery Stores R Restaurants Most of the columns in the spreadsheet are self‐explanatory. Columns H, I J, and K provide GIS mapping coordinates to assist in locating food waste generators. The Massachusetts State Plane coordinates found in the X_Coord and Y_Coord fields (Columns J and K) were derived by address‐ matching via Navteq Postal Villages. -

The Satellite Fetish Preliminary Notes on Signals Intelligence

THE SATELLITE FETISH PRELIMINARY NOTES ON SIGNALS INTELLIGENCE Pablo Colapinto Media Arts and Technology Program at the University of California Santa Barbara Submitted to Professor Marko Peljhan “The Art and Science of Aerospace Culture” Image from www.globalsecurity.org Speculated Design of the Synthetic Aperture Radar sensing Lacrosse 5 (AKA VEGA or ONYX). The Lacrosse constellation consists of four Low-Earth Orbit satellites at various inclinations and are used for high frequency radar imaging through clouds and at night. It is suspected that the resolution of the imagery is variable, with maximum estimates at 1-meter pixel resolution. This pdf briefly describes a few critical components of United States satellite intelligence in preparation for a long term video art project exploring the behavior of these spacecraft constellations, and our fascination with them. Both this preliminary study and the resultant animated work will rely heavily on the Satellite Toolkit [STK] Software developed by Analytical Graphics in Exton PA to visualize the orbital mechanics of classified payloads. It should be noted that the goal is not to “de-classify” but to “re-classify” data, to introduce a coherent personal thread into the cold and mysterious “Blackworld” of SIGINT. Many thanks to the numerous “amateur” satellite spotters who help to compose the classified.tle file essential for visualizing the orbits, to Marko Peljhan for his infectious enthusiasm and expertise on everything in orbit, and to Trevor Paglen for his illuminating talk on the subject of satellite spotting. IMAGINARY INFORMATION The visualization of “classified” data is so much fun, that even more fascinating than the data itself is our very fascination with it.