Italy Women's Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Womeninscience.Pdf

Prepared by WITEC March 2015 This document has been prepared and published with the financial support of the European Commission, in the framework of the PROGRESS project “She Decides, You Succeed” JUST/2013/PROG/AG/4889/GE DISCLAIMER This publication has been produced with the financial support of the PROGRESS Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of WITEC (The European Association for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Partners 2 Index 1. CONTENTS 2. FOREWORD5 ...........................................................................................................................................................6 3. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................7 4. PART 1 – THE CASE OF ITALY .......................................................................................................13 4.1 STATE OF PLAY .............................................................................................................................14 4.2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................18 4.3 BARRIERS AND ENABLERS .........................................................................................................19 4.4 BEST PRACTICES .........................................................................................................................20 -

Unemployment Rates in Italy Have Not Recovered from Earlier Economic

The 2017 OECD report The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle explores how gender inequalities persist in social and economic life around the world. Young women in OECD countries have more years of schooling than young men, on average, but women are less still likely to engage in paid work. Gaps widen with age, as motherhood typically has negative effects on women's pay and career advancement. Women are also less likely to be entrepreneurs, and are under-represented in private and public leadership. In the face of these challenges, this report assesses whether (and how) countries are closing gender gaps in education, employment, entrepreneurship, and public life. The report presents a range of statistics on gender gaps, reviews public policies targeting gender inequality, and offers key policy recommendations. Italy has much room to improve in gender equality Unemployment rates in Italy have not recovered from The government has made efforts to support families with earlier economic crises, and Italian women still have one childcare through a voucher system, but regional disparities of the lowest labour force participation rates in the OECD. persist. Improving access to childcare should help more The small number of women in the workforce contributes women enter work, given that Italian women do more than to Italy having one of the lowest gender pay gaps in the three-quarters of all unpaid work (e.g. care for dependents) OECD: those women who do engage in paid work are in the home. Less-educated Italian women with children likely to be better-educated and have a higher earnings face especially high barriers to paid work. -

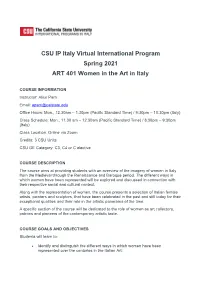

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401 Women in the Art in Italy COURSE INFORMATION Instructor: Alice Parri Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon., 12.30am – 1.30pm (Pacific Standard Time) / 9:30pm – 10:30pm (Italy) Class Schedule: Mon., 11.30 am – 12.30am (Pacific Standard Time) / 8:30pm – 9:30pm (Italy) Class Location: Online via Zoom Credits: 3 CSU Units CSU GE Category: C3, C4 or C elective COURSE DESCRIPTION The course aims at providing students with an overview of the imagery of women in Italy from the Medieval through the Renaissance and Baroque period. The different ways in which women have been represented will be explored and discussed in connection with their respective social and cultural context. Along with the representation of women, the course presents a selection of Italian female artists, painters and sculptors, that have been celebrated in the past and still today for their exceptional qualities and their role in the artistic panorama of the time. A specific section of the course will be dedicated to the role of women as art collectors, patrons and pioneers of the contemporary artistic taste. COURSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Students will learn to: • Identify and distinguish the different ways in which women have been represented over the centuries in the Italian Art; • Outline the imagery of women in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque period in connection with specific interpretations, meanings and functions attributed in their respective cultural context; • Recognize and discuss upon the Italian women artists; • Examine and discuss upon the role of Italian women as art collector and patrons. -

Why Are Fertility and Women's Employment Rates So Low in Italy?

IZA DP No. 1274 Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca Silvia Pasqua Chiara Pronzato DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER August 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca University of Turin, CHILD and IZA Bonn Silvia Pasqua University of Turin and CHILD Chiara Pronzato University of Turin and CHILD Discussion Paper No. 1274 August 2004 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. -

OECD EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK – ISBN 92-64-19778-8 – ©2002 62 – Women at Work: Who Are They and How Are They Faring?

Chapter 2 Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? This chapter analyses the diverse labour market experiences of women in OECD countries using comparable and detailed data on the structure of employment and earnings by gender. It begins by documenting the evolution of the gender gap in employment rates, taking account of differences in working time and how women’s participation in paid employment varies with age, education and family situation. Gender differences in occupation and sector of employment, as well as in pay, are then analysed for wage and salary workers. Despite the sometimes strong employment gains of women in recent decades, a substantial employment gap remains in many OECD countries. Occupational and sectoral segmentation also remains strong and appears to result in an under-utilisation of women’s cognitive and leadership skills. Women continue to earn less than men, even after controlling for characteristics thought to influence productivity. The gender gap in employment is smaller in countries where less educated women are more integrated into the labour market, but occupational segmentation tends to be greater and the aggregate pay gap larger. Less educated women and mothers of two or more children are considerably less likely to be in employment than are women with a tertiary qualification or without children. Once in employment, these women are more concentrated in a few, female-dominated occupations. In most countries, there is no evidence of a wage penalty attached to motherhood, but their total earnings are considerably lower than those of childless women, because mothers more often work part time. -

The Female Condition During Mussolini's and Salazar's Regimes

The Female Condition During Mussolini’s and Salazar’s Regimes: How Official Political Discourses Defined Gender Politics and How the Writers Alba de Céspedes and Maria Archer Intersected, Mirrored and Contested Women’s Role in Italian and Portuguese Society Mariya Ivanova Chokova Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Prerequisite for Honors In Italian Studies April 2013 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter I: The Italian Case – a historical overview of Mussolini’s gender politics and its ideological ramifications…………………………………………………………………………..6 I. 1. History of Ideology or Ideology of History……………………………………………7 1.1. Mussolini’s personal charisma and the “rape of the masses”…………………………….7 1.2. Patriarchal residues in the psychology of Italians: misogyny as a trait deeply embedded, over the centuries, in the (sub)conscience of European cultures……………………………...8 1.3. Fascism’s role in the development and perpetuation of a social model in which women were necessarily ascribed to a subaltern position……………………………………………10 1.4. A pressing need for a misogynistic gender politics? The post-war demographic crisis and the Role of the Catholic Church……………………………………………………………..12 1.5. The Duce comes in with an iron fist…………………………………………………….15 1.6. Fascist gender ideology and the inconsistencies and controversies within its logic…….22 Chapter II: The Portuguese Case – Salazar’s vision of woman’s role in Portuguese society………………………………………………………………………………………..28 II. 2.1. Gender ideology in Salazar’s Portugal.......................................................................29 2.2. The 1933 Constitution and the social place it ascribed to Portuguese women………….30 2.3. The role of the Catholic Church in the construction and justification of the New State’s gender ideology: the Vatican and Lisbon at a crossroads……………………………………31 2 2.4. -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and -

Are Foreign Women Competitive in the Marriage Market? Evidence from a New Immigration Country

Are Foreign Women Competitive in the Marriage Market? Evidence from a New Immigration Country Daniele Vignoli1,2 – Alessandra Venturini2,3 – Elena Pirani1 1University of Florence 2 Migration Policy Centre – European University Institute 3University of Torino Short paper prepared for the 2015 PAA Annual Meeting, San Diego, California, April 30 – May 2. This is only an initial draft – Please do not quote or circulate ABSTRACT Whereas empirical studies concentrating on individual-level determinants of marital disruption have a long tradition, the impact of contextual-level determinants is much less studied. In this paper we advance the hypothesis that the size (and the composition) of the presence of foreign women in a certain area affect the dissolution risk of established marriages. Using data from the 2009 survey Family and Social Subjects, we estimate a set of multilevel discrete-time event history models to study the de facto separation of Italian marriages. Aggregate-level indicators, referring to the level and composition of migration, are our main explanatory variables. We find that while foreign women are complementary to Italian women within the labor market, the increasing presence of first mover’s foreign women (especially coming from Latin America and some countries of Eastern Europe) is associated with elevated separation risks. These results proved to be robust to migration data stemming from different sources. 1 1. Motivation Europe has witnessed a substantial increase in the incidence of marital disruption in recent decades. This process is most advanced in Nordic countries, where more than half of marriages ends in divorce, followed by Western, and Central and Eastern European countries (Sobotka and Toulemon 2008; Prskawetz et al. -

Women's Work Histories in Italy

DemoSoc Working Paper Paper Number 2007--19 Women’s Work Histories in Italy: Education as Investment in Reconciliation and Legitimacy? Cristina Solera E-mail: [email protected] and Francesca Bettio E-mail: [email protected] April, 2007 Department of Political & Social Sciences Universitat Pompeu Fabra Ramon Trias Fargas, 25-27 08005 Barcelona http://www.upf.edu/dcpis/ Abstract Within pre-enlargement Europe, Italy records one of the widest employment rate gaps between highly and poorly educated women, as well one of the largest differences in the share, among working women, of public sector employment. Building on these stylized facts and using the Longitudinal Survey of Italian Households (ILFI), we investigate the working trajectories of three cohorts of Italian women born between 1935 and 1964 and observed from their first job until they are in their forties. We use mainly, but not exclusively, event history analysis in order to identify the main factors that influence entry into and exit from paid work over the life course. Our results suggest that in the Italian context, where employment protection policies have also been used as surrogate measures to favour reconciliation between family and work, and where traditional gender norms still persist, education is so important for women’s employment decisions because it represents an investment in ‘reconciliation’ and ‘work legitimacy’ over and above investment in human capital. Keywords Female participation, lifetime employment patterns, non-monetary returns to education, public sector employment Acknowledgements This paper was presented at the ESF SCSS Workshop on “Revisiting the concepts of contract and status under changing employment, welfare, and gender relations’, University of Sussex (6-8 October 2005); at Social Science Departmental Seminars, University of Torino (30 January 2006); and at the Research Forum of Political and Social Science, University of Pompeu Fabra (16 March 2007). -

Backlash in Gender Equality and Women's and Girls' Rights

STUDY Requested by the FEMM committee Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights WOMEN’S RIGHTS & GENDER EQUALITY Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union PE 604.955– June 2018 EN Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee, is designed to identify in which fields and by which means the backlash in gender equality and women’s and girls’ rights in six countries (Austria, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia) is occurring. The backlash, which has been happening over the last several years, has decreased the level of protection of women and girls and reduced access to their rights. ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Women's Rights and Gender Equality and commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizen's Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU external and internal policies. To contact the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs or to subscribe to its newsletter please write to: [email protected] RESPONSIBLE RESEARCH ADMINISTRATOR Martina SCHONARD Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] AUTHORS Borbála JUHÁSZ, indipendent expert to EIGE dr. -

Italy: Good Practices to Prevent Women Migrant Workers from Going Into Exploitive Forms of Labour

GENPROM Working Paper No. 4 Series on Women and Migration ITALY: GOOD PRACTICES TO PREVENT WOMEN MIGRANT WORKERS FROM GOING INTO EXPLOITATIVE FORMS OF LABOUR by Giuseppina D’Alconzo, Simona La Rocca and Elena Marioni Gender Promotion Programme International Labour Office Geneva Foreword Changing labour markets with globalization have increased both opportunities and pressures for women to migrate. The migration process and employment in a country of which they are not nationals can enhance women’s earning opportunities, autonomy and empowerment, and thereby change gender roles and responsibilities and contribute to gender equality. But they also expose women to serious violation of their human rights. Whether in the recruitment stage, the journey or living and working in another country, women migrant workers, especially those in irregular situations, are vulnerable to harassment, intimidation or threats to themselves and their families, economic and sexual exploitation, racial discrimination and xenophobia, poor working conditions, increased health risks and other forms of abuse, including trafficking into forced labour, debt bondage, involuntary servitude and situations of captivity. Women migrant workers, whether documented or undocumented, are much more vulnerable to discrimination, exploitation and abuse – relative not only to male migrants but also to native-born women. Gender-based discrimination intersects with discrimination based on other forms of “otherness” – such as non-national status, race, ethnicity, religion, economic status – placing women migrants in situations of double, triple or even fourfold discrimination, disadvantage or vulnerability to exploitation and abuse. To enhance the knowledge base and to develop practical tools for protecting and promoting the rights of female migrant workers, a series of case studies were commissioned. -

Supporting Women in the Luxury Supply Chain: a Focus on Italy

RESEARCH REPORT NOVEMBER 2019 Supporting Women in the Luxury Supply Chain: A Focus on Italy BSR | Supporting Women in Luxury Supply Chains: a Focus on Italy 1 Contents About This Report 2 Executive Summary 4 Engaging Suppliers on Gender Equality 12 Gender Equality in the Italian Luxury Supply Chain 15 Supporting Women in the Italian Luxury Supply Chain—a Path 32 Forward Appendix 41 BSR | Supporting Women in Luxury Supply Chains: a Focus on Italy 2 About This Report Luxury brands have committed to supporting women’s empowerment across their value chains. Women not only represent a significant share of luxury brands’ customers and employees, they are also a critical part of luxury companies’ supply chains. Italy, in particular, is well known for being a primary sourcing country for the sector, yet the status of women in the supply chain and opportunities to support women’s economic and social empowerment remain largely unknown and unaddressed. Across many different countries, women face multiple barriers to achieving gender equality. These include: » Economic barriers such as overall low labor force participation, high proportion in the informal sector, prevalence in part-time roles, challenges advancing in their careers and into leadership and decision-making roles, unequal compensation levels, and a disproportionate amount of unpaid care work. » Social barriers such as high rates of gender-based violence and harassment, challenges accessing sexual and reproductive health services, migration and human trafficking risks, weak implementation of anti-discrimination laws, traditional roles of women in society and in the workplace, and hidden gender biases and social norms that are difficult to eradicate.