Supporting Women in the Luxury Supply Chain: a Focus on Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release 05.06.2021

PRESS RELEASE 05.06.2021 REPURCHASE OF OWN SHARES FOR ALLOCATION TO FREE SHARE GRANT PROGRAMS FOR THE BENEFIT OF EMPLOYEES Within the scope of its share repurchase program authorized by the April 22, 2021 shareholders' meeting (14th resolution), Kering has entrusted an investment service provider to acquire up to 200,000 ordinary Kering shares, representing close to 0.2% of its share capital as at April 15, 2021, no later than June 25, 2021 and subject to market conditions. These shares will be allocated to free share grant programs to some employees. The unit purchase price may not exceed the maximum set by the April 22, 2021 shareholders' meeting. As part of the previous repurchase announced on February 22, 2021 (with a deadline of April 16, 2021), Kering bought back 142,723 of its own shares. About Kering A global Luxury group, Kering manages the development of a series of renowned Houses in Fashion, Leather Goods, Jewelry and Watches: Gucci, Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Balenciaga, Alexander McQueen, Brioni, Boucheron, Pomellato, DoDo, Qeelin, Ulysse Nardin, Girard-Perregaux, as well as Kering Eyewear. By placing creativity at the heart of its strategy, Kering enables its Houses to set new limits in terms of their creative expression while crafting tomorrow’s Luxury in a sustainable and responsible way. We capture these beliefs in our signature: “Empowering Imagination”. In 2020, Kering had over 38,000 employees and revenue of €13.1 billion. Contacts Press Emilie Gargatte +33 (0)1 45 64 61 20 [email protected] Marie de Montreynaud +33 (0)1 45 64 62 53 [email protected] Analysts/investors Claire Roblet +33 (0)1 45 64 61 49 [email protected] Laura Levy +33 (0)1 45 64 60 45 [email protected] www.kering.com Twitter: @KeringGroup LinkedIn: Kering Instagram: @kering_official YouTube: KeringGroup Press release 05.06.2021 1/1 . -

Womeninscience.Pdf

Prepared by WITEC March 2015 This document has been prepared and published with the financial support of the European Commission, in the framework of the PROGRESS project “She Decides, You Succeed” JUST/2013/PROG/AG/4889/GE DISCLAIMER This publication has been produced with the financial support of the PROGRESS Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of WITEC (The European Association for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Partners 2 Index 1. CONTENTS 2. FOREWORD5 ...........................................................................................................................................................6 3. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................7 4. PART 1 – THE CASE OF ITALY .......................................................................................................13 4.1 STATE OF PLAY .............................................................................................................................14 4.2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................18 4.3 BARRIERS AND ENABLERS .........................................................................................................19 4.4 BEST PRACTICES .........................................................................................................................20 -

Unemployment Rates in Italy Have Not Recovered from Earlier Economic

The 2017 OECD report The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle explores how gender inequalities persist in social and economic life around the world. Young women in OECD countries have more years of schooling than young men, on average, but women are less still likely to engage in paid work. Gaps widen with age, as motherhood typically has negative effects on women's pay and career advancement. Women are also less likely to be entrepreneurs, and are under-represented in private and public leadership. In the face of these challenges, this report assesses whether (and how) countries are closing gender gaps in education, employment, entrepreneurship, and public life. The report presents a range of statistics on gender gaps, reviews public policies targeting gender inequality, and offers key policy recommendations. Italy has much room to improve in gender equality Unemployment rates in Italy have not recovered from The government has made efforts to support families with earlier economic crises, and Italian women still have one childcare through a voucher system, but regional disparities of the lowest labour force participation rates in the OECD. persist. Improving access to childcare should help more The small number of women in the workforce contributes women enter work, given that Italian women do more than to Italy having one of the lowest gender pay gaps in the three-quarters of all unpaid work (e.g. care for dependents) OECD: those women who do engage in paid work are in the home. Less-educated Italian women with children likely to be better-educated and have a higher earnings face especially high barriers to paid work. -

Italy Women's Rights

October 2019 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE UPR OF ITALY WOMEN’S RIGHTS CONTENTS Context .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Gender stereotypes and discrimination ..................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 5 Violence against women, femicide and firearms ....................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 6 VAW: prevention, protection and the need for integrated policies at the national and regional levels . 7 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 7 Violence against women: access to justice ................................................................................................ 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sexual and reproductive health and rights ............................................................................................. 10 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................... -

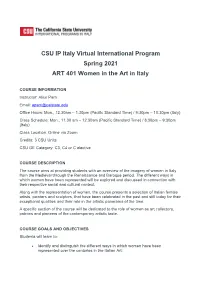

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401 Women in the Art in Italy COURSE INFORMATION Instructor: Alice Parri Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon., 12.30am – 1.30pm (Pacific Standard Time) / 9:30pm – 10:30pm (Italy) Class Schedule: Mon., 11.30 am – 12.30am (Pacific Standard Time) / 8:30pm – 9:30pm (Italy) Class Location: Online via Zoom Credits: 3 CSU Units CSU GE Category: C3, C4 or C elective COURSE DESCRIPTION The course aims at providing students with an overview of the imagery of women in Italy from the Medieval through the Renaissance and Baroque period. The different ways in which women have been represented will be explored and discussed in connection with their respective social and cultural context. Along with the representation of women, the course presents a selection of Italian female artists, painters and sculptors, that have been celebrated in the past and still today for their exceptional qualities and their role in the artistic panorama of the time. A specific section of the course will be dedicated to the role of women as art collectors, patrons and pioneers of the contemporary artistic taste. COURSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Students will learn to: • Identify and distinguish the different ways in which women have been represented over the centuries in the Italian Art; • Outline the imagery of women in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque period in connection with specific interpretations, meanings and functions attributed in their respective cultural context; • Recognize and discuss upon the Italian women artists; • Examine and discuss upon the role of Italian women as art collector and patrons. -

Alexander Mcqueen Bottega Veneta Burberry Coach

This PDF contains original work for my copywriting portfolio. These samples have been written for this sole purpose and have no affiliation to any companies or websites. Alexander McQueen Butterfly Print Silk Scarf “Alexander McQueen may have a reputation for all things gothic, but the British label switches up the formula with this scarf from its SS20 collection. Cut from lightweight silk chiffon with delicate fringed edges, it clashes the usual skull motif with borders of colourful butterflies. Wrap yours around one of the house's studded leather jackets.” Bottega Veneta Intrecciato Leather Wallet “With Daniel Lee heading up its latest collection, Bottega Veneta continues to prove its expertise in leather craftsmanship with accessories like this billfold wallet. Cut from smooth nappa calfskin, it’s covered in the classic geometric squares of the Italian label’s iconic Intrecciato weave. Open it up and you’ll find eight card slots and two note compartments for your cash.” Burberry Thomas Bear Leather Bag Charm “If you’re a fan of Burberry, you’ll know that each season the British label drops a new version of its famous (and impeccably dressed) little teddy charm. This time around, Thomas Bear is reworked in leather with a cotton trench coat and completely covered in the house’s new TB monogram. It’s fitted with a polished lobster clasp fastening to easily clip to your favourite bag.” Coach © Thomas Arthur Charlie Leather Tote “Coach plays up its iconic branding in its SS20 collection with the Charlie tote. Cut from the label’s signature coated canvas, it’s covered with an interlocking monogram print that’s understated enough for the office and detailed with silver-tone hardware. -

Why Are Fertility and Women's Employment Rates So Low in Italy?

IZA DP No. 1274 Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca Silvia Pasqua Chiara Pronzato DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER August 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca University of Turin, CHILD and IZA Bonn Silvia Pasqua University of Turin and CHILD Chiara Pronzato University of Turin and CHILD Discussion Paper No. 1274 August 2004 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. -

Knowthehcain I Questions Regarding Forced Labour Risks in Your Company’S Leather Supply Chain

KNOWTHEHCAIN I QUESTIONS REGARDING FORCED LABOUR RISKS IN YOUR COMPANY’S LEATHER SUPPLY CHAIN In countries including but not limited to Pakistan, Bangladesh and India, leather processing is characterised by hazardous and poor working conditions, which may be early indicators or eventually lead to forced labour.1 In countries including India and China forced labour risks have been documented. Through this questionnaire, KnowTheChain would like to get a better understanding of how your company is addressing risks related to forced labour specifically in its leather supply chain. In answering these questions, please indicate where your company’s policies or practices specifically apply to cattle sourcing, leather processing or leather goods manufacturing countries at risk of forced labour and human trafficking such as Brazil, China and India2 or other countries where you might have identified forced labour risks. Traceability: 1. Leather goods manufacturing: a. In which countries does your company and/or your suppliers manufacture leather goods (option to indicate percentage or volume of supply from each country)? b. What are the names and addresses of your company’s and/or your suppliers’ leather goods manufacturers? Please indicate the nature of your relationship to them, e.g. direct owned or purchasing only (option to indicate workforce data you deem relevant, such as workforce composition (e.g. percentage of informal/migrant/female workforce) or rate of unionisation). What are the names of the persons legally responsible for the production facilities? 2. Leather processing / tanneries: a. In which countries does your company and/or your suppliers process and produce leather? b. What are the names and addresses of your company’s and/or your suppliers’ tanneries? Please indicate the nature of your relationship to them, e.g. -

OECD EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK – ISBN 92-64-19778-8 – ©2002 62 – Women at Work: Who Are They and How Are They Faring?

Chapter 2 Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? This chapter analyses the diverse labour market experiences of women in OECD countries using comparable and detailed data on the structure of employment and earnings by gender. It begins by documenting the evolution of the gender gap in employment rates, taking account of differences in working time and how women’s participation in paid employment varies with age, education and family situation. Gender differences in occupation and sector of employment, as well as in pay, are then analysed for wage and salary workers. Despite the sometimes strong employment gains of women in recent decades, a substantial employment gap remains in many OECD countries. Occupational and sectoral segmentation also remains strong and appears to result in an under-utilisation of women’s cognitive and leadership skills. Women continue to earn less than men, even after controlling for characteristics thought to influence productivity. The gender gap in employment is smaller in countries where less educated women are more integrated into the labour market, but occupational segmentation tends to be greater and the aggregate pay gap larger. Less educated women and mothers of two or more children are considerably less likely to be in employment than are women with a tertiary qualification or without children. Once in employment, these women are more concentrated in a few, female-dominated occupations. In most countries, there is no evidence of a wage penalty attached to motherhood, but their total earnings are considerably lower than those of childless women, because mothers more often work part time. -

The Female Condition During Mussolini's and Salazar's Regimes

The Female Condition During Mussolini’s and Salazar’s Regimes: How Official Political Discourses Defined Gender Politics and How the Writers Alba de Céspedes and Maria Archer Intersected, Mirrored and Contested Women’s Role in Italian and Portuguese Society Mariya Ivanova Chokova Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Prerequisite for Honors In Italian Studies April 2013 Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………4 Chapter I: The Italian Case – a historical overview of Mussolini’s gender politics and its ideological ramifications…………………………………………………………………………..6 I. 1. History of Ideology or Ideology of History……………………………………………7 1.1. Mussolini’s personal charisma and the “rape of the masses”…………………………….7 1.2. Patriarchal residues in the psychology of Italians: misogyny as a trait deeply embedded, over the centuries, in the (sub)conscience of European cultures……………………………...8 1.3. Fascism’s role in the development and perpetuation of a social model in which women were necessarily ascribed to a subaltern position……………………………………………10 1.4. A pressing need for a misogynistic gender politics? The post-war demographic crisis and the Role of the Catholic Church……………………………………………………………..12 1.5. The Duce comes in with an iron fist…………………………………………………….15 1.6. Fascist gender ideology and the inconsistencies and controversies within its logic…….22 Chapter II: The Portuguese Case – Salazar’s vision of woman’s role in Portuguese society………………………………………………………………………………………..28 II. 2.1. Gender ideology in Salazar’s Portugal.......................................................................29 2.2. The 1933 Constitution and the social place it ascribed to Portuguese women………….30 2.3. The role of the Catholic Church in the construction and justification of the New State’s gender ideology: the Vatican and Lisbon at a crossroads……………………………………31 2 2.4. -

Important Jewelry

IMPORTANT JEWELRY Wednesday, December 14, 2016 NEW YORK IMPORTANT JEWELRY AUCTION Wednesday, December 14, 2016 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, December 10, 10am – 5pm Sunday, December 11, 12pm – 5pm Monday, December 12, 10am – 5pm Tuesday, December 13, 10am – 2pm LOCATION ?? ????????? ??????????????????????????????? Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com www.Dwww.Doyle.com/BidLiveoyleNewYork.com/BidLive Catalogue: $45 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM CONTENTS THE ESTATES OF Important Jewelry 1-396 Elsie Adler Conditions of Sale I A New York Estate Terms of Guarantee III A New York and Connecticut Estate Buying at Doyle IV The Thurston Collection Company Directory VI Absentee Bid Form VIII INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM An European Collector A Lady, Montreal, Canada A Prominent New York Family Sold to Benefit Charities of the United Nations A Washington, DC Collector A Washington, DC Lady Lot 393 image enlarged 1 6 3 2 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pair of Gold and Black Jade Pair of Gold and Black Jade Gold and Black Jade Bangle Pair of Gold and Mother-of-Pearl Long Gold Chain Necklace, Pair of Gold and Black Jade Earclips, Tiffany & Co. Earclips, Tiffany & Co. Bracelet, Tiffany & Co. Earclips, Tiffany & Co. Tiffany & Co. ‘Positive Negative’ Earclips, Tiffany & Co. 18 kt., the modified 18 kt., the square-shaped 18 kt., the polished gold bombé 18 kt., the square-shaped 18 kt., composed of polished 18 kt., one oval bombé gold earclip spotted triangular-shaped polished gold polished gold panels inlaid with bangle of oval shape inlaid with polished gold panels inlaid with interlocking oval links, signed T & Co., with rounded triangular-shaped inlaid black panels inlaid with alternating black jade in a checkerboard alternating black jade bands, square-shaped mother-of-pearl approximately 135.6 dwts. -

FAIRMINED LICENSEE LIST 2019 Last Update: 18/01/2019

FAIRMINED LICENSEE LIST 2019 Last Update: 18/01/2019 COUNTRY BRAND WEBSITE Australia Zoe Pook Jewellery https://zoepook.com.au/ Austria Caroline Kerschbaumer http://www.carolinekerschbaumer.at Florian-Julian Fichtinger http://florianjulianfichtinger.com/ Goldschmiede Matthias http://www.pfoetscher.at/ Pfoetscher Goldschmiede Nikl https://www.nikl.at/ Belgium CAP Source http://www.capsource.be/ EbbenGouD www.ebbengoud.be Frank and Daisy https://frankxdaisy.com/ Nele Braet jewelry Nelebraet.be Saskia Shutt Designs www.saskiashutt.com Brasil Ana Khouri http://anakhouri.com/ Canada FairSources https://ftjco.com/ Flamme en rose www.flammeenrose.com Fluid Jewellery https://www.fluidjewellery.com/ Hume Atelier http://humeatelier.com/ Millmibi Modelfik https://www.facebook.com/Modelfik/ PROUD maddison www.proudmaddison.com Colombia Arque-Arte https://www.arquejoyas.com/ Colombia Eden Jewelry SAS http://www.edenjoyas.com Elena Montenegro Eulogia https://www.eulogia.com.co/ JVR Joyería https://www.facebook.com/svrbisuteria/ https://www.facebook.com/pages/category/Inter Maoca Joyeria est/MAOCA-Joyeria-190842151295459/ Moda Elan www.ModaElan.com NIKA www.nika.com.co Ruiz Orfebres www.facebook.com/RUIZorfebres Silvia Segura https://www.facebook.com/silviasegurajoyeria/ Simon Mazuera http://simonmazuera.com/ Tundama Joyeros http://tundamajoyeros.com/ Denmark Anna Moltke-Huitfeldt http://www.moltke-huitfeldt.com/ Ole Mathiesen https://olemathiesen.dk Sophie Rose Instagram: sophierose_ddk Finland Galleria Koru www.galleriakoru.com France Ame Méthys http://www.ame-methys.com/