The Female Condition During Mussolini's and Salazar's Regimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/01/2021 07:59:52PM Via Free Access Fedele: ‘Holistic Mothers’ Or ‘Bad Mothers’? Challenging Biomedical Models of the Body

Vol. 6, no. 1 (2016), 95-111 | DOI: 10.18352/rg.10128 ‘Holistic Mothers’ or ‘Bad Mothers’? Challenging Biomedical Models of the Body in Portugal ANNA FEDELE* Abstract This paper is based on early fieldwork findings on ‘holistic mothering’ in contemporary Portugal. I use holistic mothering as an umbrella term to cover different mothering choices, which are rooted in the assumption that pregnancy, childbirth and early childhood are important spiritual occasions for both mother and child. Considering that little social scientific literature exists about the religious dimension of alternative mothering choices, I present here a first description of this phenomenon and offer some initial anthropological reflections, paying special attention to the influence of Goddess spirituality on holistic mothers. Drawing on Pamela Klassen’s ethnography about religion and home birth in America (2001), I argue that in Portugal holistic mothers are challenging biomedical models of the body, asking for a more woman-centred care, and contributing to the process, already widespread in certain other European countries, of ‘humanising’ pregnancy and childbirth. Keywords Holistic Mothering; Goddess spirituality; Portugal; CAM; biomedicine; homebirth. Author affiliation Anna Fedele holds a PhD in Social and Cultural Anthropology from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris) and the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. She is a Senior Researcher at the Centre for Research in Anthropology (CRIA) at the Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Lisboa, Portugal. Her award-winning book Looking for Mary Magdalene: Alternative Pilgrimage and Ritual Creativity at Catholic Shrines in France was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. *Correspondence: CRIA, Av. Forças Armadas, Ed. -

Womeninscience.Pdf

Prepared by WITEC March 2015 This document has been prepared and published with the financial support of the European Commission, in the framework of the PROGRESS project “She Decides, You Succeed” JUST/2013/PROG/AG/4889/GE DISCLAIMER This publication has been produced with the financial support of the PROGRESS Programme of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of WITEC (The European Association for Women in Science, Engineering and Technology) and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Commission. Partners 2 Index 1. CONTENTS 2. FOREWORD5 ...........................................................................................................................................................6 3. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................7 4. PART 1 – THE CASE OF ITALY .......................................................................................................13 4.1 STATE OF PLAY .............................................................................................................................14 4.2 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................................................18 4.3 BARRIERS AND ENABLERS .........................................................................................................19 4.4 BEST PRACTICES .........................................................................................................................20 -

Unemployment Rates in Italy Have Not Recovered from Earlier Economic

The 2017 OECD report The Pursuit of Gender Equality: An Uphill Battle explores how gender inequalities persist in social and economic life around the world. Young women in OECD countries have more years of schooling than young men, on average, but women are less still likely to engage in paid work. Gaps widen with age, as motherhood typically has negative effects on women's pay and career advancement. Women are also less likely to be entrepreneurs, and are under-represented in private and public leadership. In the face of these challenges, this report assesses whether (and how) countries are closing gender gaps in education, employment, entrepreneurship, and public life. The report presents a range of statistics on gender gaps, reviews public policies targeting gender inequality, and offers key policy recommendations. Italy has much room to improve in gender equality Unemployment rates in Italy have not recovered from The government has made efforts to support families with earlier economic crises, and Italian women still have one childcare through a voucher system, but regional disparities of the lowest labour force participation rates in the OECD. persist. Improving access to childcare should help more The small number of women in the workforce contributes women enter work, given that Italian women do more than to Italy having one of the lowest gender pay gaps in the three-quarters of all unpaid work (e.g. care for dependents) OECD: those women who do engage in paid work are in the home. Less-educated Italian women with children likely to be better-educated and have a higher earnings face especially high barriers to paid work. -

Italy Women's Rights

October 2019 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE UPR OF ITALY WOMEN’S RIGHTS CONTENTS Context .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Gender stereotypes and discrimination ..................................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 5 Violence against women, femicide and firearms ....................................................................................... 4 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 6 VAW: prevention, protection and the need for integrated policies at the national and regional levels . 7 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 7 Violence against women: access to justice ................................................................................................ 8 Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 9 Sexual and reproductive health and rights ............................................................................................. 10 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................... -

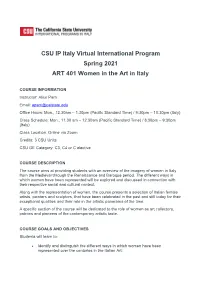

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401

CSU IP Italy Virtual International Program Spring 2021 ART 401 Women in the Art in Italy COURSE INFORMATION Instructor: Alice Parri Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Mon., 12.30am – 1.30pm (Pacific Standard Time) / 9:30pm – 10:30pm (Italy) Class Schedule: Mon., 11.30 am – 12.30am (Pacific Standard Time) / 8:30pm – 9:30pm (Italy) Class Location: Online via Zoom Credits: 3 CSU Units CSU GE Category: C3, C4 or C elective COURSE DESCRIPTION The course aims at providing students with an overview of the imagery of women in Italy from the Medieval through the Renaissance and Baroque period. The different ways in which women have been represented will be explored and discussed in connection with their respective social and cultural context. Along with the representation of women, the course presents a selection of Italian female artists, painters and sculptors, that have been celebrated in the past and still today for their exceptional qualities and their role in the artistic panorama of the time. A specific section of the course will be dedicated to the role of women as art collectors, patrons and pioneers of the contemporary artistic taste. COURSE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES Students will learn to: • Identify and distinguish the different ways in which women have been represented over the centuries in the Italian Art; • Outline the imagery of women in Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque period in connection with specific interpretations, meanings and functions attributed in their respective cultural context; • Recognize and discuss upon the Italian women artists; • Examine and discuss upon the role of Italian women as art collector and patrons. -

Why Are Fertility and Women's Employment Rates So Low in Italy?

IZA DP No. 1274 Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca Silvia Pasqua Chiara Pronzato DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES DISCUSSION PAPER August 2004 Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Why Are Fertility and Women’s Employment Rates So Low in Italy? Lessons from France and the U.K. Daniela Del Boca University of Turin, CHILD and IZA Bonn Silvia Pasqua University of Turin and CHILD Chiara Pronzato University of Turin and CHILD Discussion Paper No. 1274 August 2004 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 Email: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of the institute. Research disseminated by IZA may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit company supported by Deutsche Post World Net. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its research networks, research support, and visitors and doctoral programs. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. -

Memorandum on Combating Racism and Violence Against Women in Portugal

Country Memorandum Memorandum on combating racism and violence against women in Portugal 1. The memorandum was prepared on the basis of regular monitoring work by the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights (hereinafter, “the Commissioner”) and online exchanges held with representatives of the Portuguese authorities and of civil society organisations between 15 and 17 December 2020, replacing a country visit initially planned for November 2020, which had to be postponed owing to COVID-19-related constraints.1 2. The memorandum addresses the increasing level of racism and the persistence of related discrimination in the country and the response of the Portuguese authorities to this situation. It also covers the persistent problem of violence against women and domestic violence and the measures taken by the Portuguese authorities to combat such phenomena. 3. Online exchanges included meetings with the Minister of Justice, Francisca Van Dunem; the Minister of State and of Foreign Affairs, Augusto Santos Silva; the Minister of State and for the Presidency, Mariana Vieira da Silva; the State Secretary for Citizenship and Equality, Rosa Monteiro; the High Commissioner for Migration, Sónia Pereira; the President of the Commission for Citizenship and Gender Equality, Sandra Ribeiro; and the Minister of Internal Administration, Eduardo Cabrita. In addition, the Commissioner held talks with the Ombuds, Maria Lucia Amaral, and meetings with representatives of several civil society organisations. The Commissioner would like to express her appreciation to the Portuguese authorities in Strasbourg and in Lisbon for their kind assistance in organising and facilitating her meetings with officials. She is grateful to all the people in Portugal she spoke to for sharing their views, knowledge and insights. -

OECD EMPLOYMENT OUTLOOK – ISBN 92-64-19778-8 – ©2002 62 – Women at Work: Who Are They and How Are They Faring?

Chapter 2 Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? This chapter analyses the diverse labour market experiences of women in OECD countries using comparable and detailed data on the structure of employment and earnings by gender. It begins by documenting the evolution of the gender gap in employment rates, taking account of differences in working time and how women’s participation in paid employment varies with age, education and family situation. Gender differences in occupation and sector of employment, as well as in pay, are then analysed for wage and salary workers. Despite the sometimes strong employment gains of women in recent decades, a substantial employment gap remains in many OECD countries. Occupational and sectoral segmentation also remains strong and appears to result in an under-utilisation of women’s cognitive and leadership skills. Women continue to earn less than men, even after controlling for characteristics thought to influence productivity. The gender gap in employment is smaller in countries where less educated women are more integrated into the labour market, but occupational segmentation tends to be greater and the aggregate pay gap larger. Less educated women and mothers of two or more children are considerably less likely to be in employment than are women with a tertiary qualification or without children. Once in employment, these women are more concentrated in a few, female-dominated occupations. In most countries, there is no evidence of a wage penalty attached to motherhood, but their total earnings are considerably lower than those of childless women, because mothers more often work part time. -

Women Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation in Portugal: Life Narratives

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 1 No. 17 [Special Issue – November 2011] Women Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation in Portugal: Life narratives Ana Sofia Antunes das Neves, PhD Psychology and Communication Department Instituto Superior da Maia, Maia, Portugal Avenida Carlos Oliveira Campos – Castêlo da Maia 4475 – 690 Avioso S. Pedro Portugal Abstract This paper describes a qualitative research about women trafficking for sexual exploitation in Portugal. The life experiences of a group of Brazilian women were characterised through the use of a comprehensive methodology – life narratives. The evidences found in this study, analysed and interpreted discursively from a feminist critical perspective, show us an unmistakable and intricate articulation between gender issues and poverty and social exclusion. Those conditions seem to establish themselves risk factors for victimisation and sexual oppression. Key Words: Migration, Women trafficking, Intersectionality. 1. Introduction Social and economic instability and gender discrimination leads millions of women, around the world, to migrate to developed countries, hoping to improve their life quality. Throughout all Europe, women experience situations of great vulnerability and are frequently faced with situations of oppression and domestic and institutional violence (Freedman, 2003). Unemployment and poverty in origin countries reinforces the tendency to feminization of migrations (Castles & Miller, 2003) or, as other authors prefer to call, to gender transition (Morokvašić, 2010), one of the main features of the present era of migrations. Migration dynamics are very complex and depends on identities belongings like ethnicity, gender and age (Crenshaw, 1991), as well as other conditions such as the educational level, occupation, marital status and political and economical pressures associated to certain geographical areas (O.McKee, 2000). -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and -

Are Foreign Women Competitive in the Marriage Market? Evidence from a New Immigration Country

Are Foreign Women Competitive in the Marriage Market? Evidence from a New Immigration Country Daniele Vignoli1,2 – Alessandra Venturini2,3 – Elena Pirani1 1University of Florence 2 Migration Policy Centre – European University Institute 3University of Torino Short paper prepared for the 2015 PAA Annual Meeting, San Diego, California, April 30 – May 2. This is only an initial draft – Please do not quote or circulate ABSTRACT Whereas empirical studies concentrating on individual-level determinants of marital disruption have a long tradition, the impact of contextual-level determinants is much less studied. In this paper we advance the hypothesis that the size (and the composition) of the presence of foreign women in a certain area affect the dissolution risk of established marriages. Using data from the 2009 survey Family and Social Subjects, we estimate a set of multilevel discrete-time event history models to study the de facto separation of Italian marriages. Aggregate-level indicators, referring to the level and composition of migration, are our main explanatory variables. We find that while foreign women are complementary to Italian women within the labor market, the increasing presence of first mover’s foreign women (especially coming from Latin America and some countries of Eastern Europe) is associated with elevated separation risks. These results proved to be robust to migration data stemming from different sources. 1 1. Motivation Europe has witnessed a substantial increase in the incidence of marital disruption in recent decades. This process is most advanced in Nordic countries, where more than half of marriages ends in divorce, followed by Western, and Central and Eastern European countries (Sobotka and Toulemon 2008; Prskawetz et al. -

Women's Work Histories in Italy

DemoSoc Working Paper Paper Number 2007--19 Women’s Work Histories in Italy: Education as Investment in Reconciliation and Legitimacy? Cristina Solera E-mail: [email protected] and Francesca Bettio E-mail: [email protected] April, 2007 Department of Political & Social Sciences Universitat Pompeu Fabra Ramon Trias Fargas, 25-27 08005 Barcelona http://www.upf.edu/dcpis/ Abstract Within pre-enlargement Europe, Italy records one of the widest employment rate gaps between highly and poorly educated women, as well one of the largest differences in the share, among working women, of public sector employment. Building on these stylized facts and using the Longitudinal Survey of Italian Households (ILFI), we investigate the working trajectories of three cohorts of Italian women born between 1935 and 1964 and observed from their first job until they are in their forties. We use mainly, but not exclusively, event history analysis in order to identify the main factors that influence entry into and exit from paid work over the life course. Our results suggest that in the Italian context, where employment protection policies have also been used as surrogate measures to favour reconciliation between family and work, and where traditional gender norms still persist, education is so important for women’s employment decisions because it represents an investment in ‘reconciliation’ and ‘work legitimacy’ over and above investment in human capital. Keywords Female participation, lifetime employment patterns, non-monetary returns to education, public sector employment Acknowledgements This paper was presented at the ESF SCSS Workshop on “Revisiting the concepts of contract and status under changing employment, welfare, and gender relations’, University of Sussex (6-8 October 2005); at Social Science Departmental Seminars, University of Torino (30 January 2006); and at the Research Forum of Political and Social Science, University of Pompeu Fabra (16 March 2007).