Dedications at Ancient Dodona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy in Ancient Athens Was Different from What We Have in Canada Today

54_ALB6SS_Ch3_F2 2/13/08 2:25 PM Page 54 CHAPTER Democracy in 3 Ancient Athens Take a long step 2500 years back in time. Imagine you are a boy living in the ancient city of Athens, Greece. Your slave, words matter! Cleandros [KLEE-an-thros], is walking you to school. Your father Ancient refers to something and a group of his friends hurry past talking loudly. They are on from a time more than their way to the Assembly. The Assembly is an important part of 2500 years ago. democratic government in Athens. All Athenian men who are citizens can take part in the Assembly. They debate issues of concern and vote on laws. As the son of a citizen, you look forward to being old enough to participate in the Assembly. The Birthplace of Democracy The ancient Greeks influenced how people today think about citizenship and rights. In Athens, a form of government developed in which the people participated. The democracy we enjoy in Canada had its roots in ancient Athens. ■ How did men who were citizens participate in the democratic government in Athens? ■ Did Athens have representative government? Explain. 54 54_ALB6SS_Ch3_F2 2/13/08 2:25 PM Page 55 “Watch Out for the Rope!” Cleandros takes you through the agora, a large, open area in the middle of the city. It is filled with market stalls and men shopping and talking. You notice a slave carrying a rope covered with red paint. He ? Inquiring Minds walks through the agora swinging the rope and marking the men’s clothing with paint. -

& Special Prizes

Αthena International Olive Oil Competition 26 ΧΑΛΚΙΝΑ- 28 March ΜΕΤΑΛΛΙΑ* 2018 OLIVE OIL PRODUCER DELPHIVARIETAL MAKE-UP• PHOCIS REGION COUNTRY WEBSITE ΜEDALS & SPECIAL PRIZES Final Participation and Awards Results For its third edition the Athena International Olive Oil Competition (ATHIOOC) showed a 22% increase in the num- ber of participating samples; 359 extra virgin olive oils from 12 countries were judged by a panel of 20 interna- tional experts from 11 countries. This is the first year that the number of samples from abroad overpassed those from Greece: of the 359 samples tasted, 171 were Greek (48%) and 188 (52%) from other countries. In conjunction with the high number of inter- national judges (2/3 of the tasting panel), this establishes Athena as one of the few truly international extra virgin olive oil competitions in the world ―and one of the fastest growing ones. ATHIOOC 2018 awarded 242 medals in the following categories: 13 Double Gold (scoring 95-100%), 100 Gold (scoring 85-95%), 89 Silver (scoring 75-85%) and 40 Bronze (scoring 65-75%). There were also several special prizes including «Best of Show» which this year goes to Palacio de los Olivos from Andalusia, Spain. There is also a notable increase in the number of cultivars present: 124 this year compared to 92 last year, testify- ing to the amazing diversity of the olive oil world. The awards ceremony will take place in Athens on Saturday, April 28 2018, 18:00, at the Zappeion Megaron Con- ference & Exhibitions Hall in the city center. This event will be preceded by a day-long, stand-up and self-pour tasting of all award-winning olive oils. -

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11Th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA an Ancient City in Greece, the Capital of Laconia and the Most Powerful State of the Peloponnese

Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Sparta SPARTA AN ancient city in Greece, the capital of Laconia and the most powerful state of the Peloponnese. The city lay at the northern end of the central Laconian plain, on the right bank of the river Eurotas, a little south of the point where it is joined by its largest tributary, the Oenus (mount Kelefina). The site is admirably fitted by nature to guard the only routes by which an army can penetrate Laconia from the land side, the Oenus and Eurotas valleys leading from Arcadia, its northern neighbour, and the Langada Pass over Mt Taygetus connecting Laconia and Messenia. At the same time its distance from the sea-Sparta is 27 m. from its seaport, Gythium, made it invulnerable to a maritime attack. I.-HISTORY Prehistoric Period.-Tradition relates that Sparta was founded by Lacedaemon, son of Zeus and Taygete, who called the city after the name of his wife, the daughter of Eurotas. But Amyclae and Therapne (Therapnae) seem to have been in early times of greater importance than Sparta, the former a Minyan foundation a few miles to the south of Sparta, the latter probably the Achaean capital of Laconia and the seat of Menelaus, Agamemnon's younger brother. Eighty years after the Trojan War, according to the traditional chronology, the Dorian migration took place. A band of Dorians united with a body of Aetolians to cross the Corinthian Gulf and invade the Peloponnese from the northwest. The Aetolians settled in Elis, the Dorians pushed up to the headwaters of the Alpheus, where they divided into two forces, one of which under Cresphontes invaded and later subdued Messenia, while the other, led by Aristodemus or, according to another version, by his twin sons Eurysthenes and Procles, made its way down the Eurotas were new settlements were formed and gained Sparta, which became the Dorian capital of Laconia. -

Provided by the Internet Classics Archive. See Bottom for Copyright

Provided by The Internet Classics Archive. See bottom for copyright. Available online at http://classics.mit.edu//Homer/iliad.html The Iliad By Homer Translated by Samuel Butler ---------------------------------------------------------------------- BOOK I Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another. And which of the gods was it that set them on to quarrel? It was the son of Jove and Leto; for he was angry with the king and sent a pestilence upon the host to plague the people, because the son of Atreus had dishonoured Chryses his priest. Now Chryses had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom: moreover he bore in his hand the sceptre of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant's wreath and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove." On this the rest of the Achaeans with one voice were for respecting the priest and taking the ransom that he offered; but not so Agamemnon, who spoke fiercely to him and sent him roughly away. -

Report of the First Season 'Dimal in Illyria' 2010

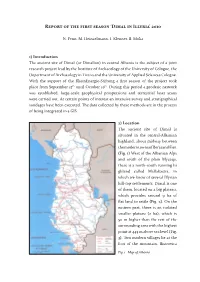

Report of the first season ‘Dimal in Illyria’ 2010 N. Fenn, M. Heinzelmann, I. Klenner, B. Muka 1) Introduction The ancient site of Dimal (or Dimallon) in central Albania is the subject of a joint research project lead by the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Cologne, the Department of Archaeology in Tirana and the University of Applied Sciences Cologne. With the support of the RheinEnergie-Stiftung a first season of the project took place from September 15th until October 19th. During this period a geodetic network was established, large-scale geophysical prospections and terrestrial laser scans were carried out. At certain points of interest an intensive survey and stratigraphical sondages have been executed. The data collected by these methods are in the process of being integrated in a GIS. 2) Location The ancient site of Dimal is situated in the central-Albanian highland, about midway between the modern towns of Berat and Fier. (Fig. 1) West of the Albanian Alps and south of the plain Myzeqe, there is a north-south running hi ghland called Mallakastra, in which we know of several Illyrian hill-top settlements. Dimal is one of them, located on a big plateau, which provides around 9 ha of flat land to settle (Fig. 2). On the eastern part, there is an isolated smaller plateau (2 ha), which is 50 m higher than the rest of the surrounding area with the highest point at 445 m above sea level (Fig. 3). Two modern villages lie at the foot of the mountain, Bistrovica Fig. 1 - Map of Albania REPORT OF THE FIRST SEASON ‘DIMAL IN ILLYRIA’ 2010 Fig. -

Herodotus' Four Markers of Greek Identity (Ch

Loyola Marymount University From the SelectedWorks of Katerina Zacharia September, 2008 Hellenisms (ii), Herodotus' Four Markers of Greek Identity (ch. 1) Katerina Zacharia, Loyola Marymount University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/katerina_zacharia/15/ 1. Herodotus’ Four Markers of Greek Identity Katerina Zacharia [...] πρὸς δὲ τοὺς ἀπὸ Σπάρτης ἀγγέλους τάδε· Τὸ μὲν δεῖσαι Λακεδαιμονίους μὴ ὁμολογήσωμεν τῷ βαρβάρῳ κάρτα ἀνθρωπήιον ἦν. ἀτὰρ αἰσχρῶς γε οἴκατε ἐξεπιστάμενοι τὸ Ἀθηναίων φρόνημα ἀρρωδῆσαι, ὅτι οὔτε χρυσός ἐστι γῆς οὐδαμόθι τοσοῦτος οὔτε χώρη καλλει καὶ ἀρετῇ μέγα ὑπερφέρουσα, τὰ ἡμεῖς δεξάμενοι ἐθέλοιμεν ἂν μηδίσαντες καταδουλῶσαι τὴν Ἑλλάδα. Πολλὰ τε γὰρ καὶ μεγαλα ἐστι τὰ διακωλύοντα ταῦτα μὴ ποιέειν μηδ᾿ ἢν ἐθέλωμεν, πρῶτα μὲν καὶ μέγιστα τῶν θεῶν τὰ ἀγάλματα καὶ τὰ οἰκήματα ἐμπεπρησμένα τε καὶ συγκεχωσμένα, τοῖσι ἡμέας ἀναγκαίως ἔχει τιμωρέειν ἐς τὰ μέγιστα μᾶλλον ἤ περ ὁμολογέειν τῷ ταῦτα ἐργασαμένῳ, αὖτις δὲ τὸ Ἑλληνικὸν, ἐὸν ὅμαιμόν τε καὶ ὁμόγλωσσον, καὶ θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι ἤθεά τε ὁμότροπα, τῶν προδότας γενέσθαι Ἀθηναίους οὐκ ἂν εὖ ἔχοι. ἐπίστασθέ τε οὕτω, εἰ μὴ καὶ πρότερον ἐτύγχανετε ἐπιστάμενοι, ἔστ᾿ ἂν καὶ εἶς περιῇ Ἀθηναίων, μηδαμὰ ὁμολογήσοντας ἡμέας Ξέρξῃ .1 Herodotus, Histories, 8, 144.1–3 1. The Sources: Some Qualifiers All contributors were invited to think about the four characteristic features of Hellenism (blood, language, religion, and customs) listed by some anonymous Athenian speakers at the end of Herodotus VIII, in the caption of this chapter. Some of the questions the contributors were asked to explore are: How far has it been true historically that these four features have acted 1 “To the Spartan envoys they said: ‘No doubt it was natural that the Lacedaemonians should dread the possibility of our making terms with Persia; none the less it shows a poor estimate of the spirit of Athens. -

Social Studies Grade 7 Week of 4-6-20 1. Log Onto Clever with Your

Social Studies Grade 7 Week of 4-6-20 1. Log onto Clever with your BPS username and password. 2. Log into Newsela 3. Copy and paste this link into your browser: https://newsela.com/subject/other/2000220316 4. Complete the readings and assignments listed. If you can’t access the articles through Newsela, they are saved as PDFs under the Grade 7 Social Studies folder on the BPSMA Learning Resources Site. They are: • Democracy: A New Idea in Ancient Greece • Ancient Greece: Democracy is Born • Green Influence on U.S. Demoracy Complete the following: Directions: Read the three articles in the text set. Remember, you can change the reading level to what is most comfortable for you. While reading, use the following protocols: Handling changes in your life is an important skill to gain, especially during these times. Use the following supports to help get the most out of these texts. Highlight in PINK any words in the text you do not understand. Highlight in BLUE anything that you have a question about. Write an annotation to ask your question. (You can highlight right in the article. Click on the word or text with your mouse. Once you let go of the mouse, the highlight/annotation box will appear on your right. You can choose the color of the highlight and write a note or question in the annotation box). Pre-Reading Activity: KWL: Complete the KWL Chart to keep your information organized. You may use the one below or create your own on a piece of paper. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OUDVcJA6hjcteIhpA0f5ssvk28WNBhlK/view Post-Reading Activity: After reading the articles, complete a Venn diagram to compare and contrast the democracy of Ancient Greece and the United States. -

Baseline Assessment Report of the Lake Ohrid Region – Albania Annex

TOWARDS STRENGTHENED GOVERNANCE OF THE SHARED TRANSBOUNDARY NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE LAKE OHRID REGION Baseline Assessment report of the Lake Ohrid region – Albania (available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/lake-ohrid-region) Annex XXIII Bibliography on cultural values and heritage, agriculture and tourism aspects of the Lake Ohrid region prepared by Luisa de Marco, Maxim Makartsev and Claudia Spinello on behalf of ICOMOS. January 2016 BIBLIOGRAPHY1 2015 The present bibliography focusses mainly on the cultural values and heritage, agriculture and tourism aspects of the Lake Ohrid region (LOR). It should be read in conjunction to the Baseline Assessment report prepared in a joint collaboration between ICOMOS and IUCN (available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/lake-ohrid-region) The bibliography includes all the relevant titles from the digital catalogue of the Albanian National Library for the geographic terms connected to LOR. The bibliography includes all the relevant titles from the systematic catalogue since 1989 to date, for the categories 9-908; 91-913 (4/9) (902. Archeology; 903. Prehistory. Prehistoric remains, antiquities. 904. Cultural remains of the historic times. 908. Regional studies. Studies of a place. 91. Geography. The exploration of the land and of specific places. Travels. Regional geography). It also includes the relevant titles found on www.scholar.google.com with summaries if they are provided or if the text is available. Three bibliographies for archaeology and ancient history of Albania were used: Bep Jubani’s (1945-1971); Faik Drini’s (1972-1983); V. Treska’s (1995-2000). A bibliography for the years 1984-1994 (authors: M.Korkuti, Z. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

Land Routes in Aetolia (Greece)

Yvette Bommeljé The long and winding road: land routes in Aetolia Peter Doorn (Greece) since Byzantine times In one or two years from now, the last village of the was born, is the northern part of the research area of the southern Pindos mountains will be accessible by road. Aetolian Studies Project. In 1960 Bakogiánnis had Until some decades ago, most settlements in this backward described how his native village of Khelidón was only region were only connected by footpaths and mule tracks. connected to the outside world by what are called karélia In the literature it is generally assumed that the mountain (Bakogiánnis 1960: 71). A karéli consists of a cable population of Central Greece lived in isolation. In fact, a spanning a river from which hangs a case or a rack with a dense network of tracks and paths connected all settlements pulley. The traveller either pulls himself and his goods with each other, and a number of main routes linked the to the other side or is pulled by a helper. When we area with the outside world. visited the village in 1988, it could still only be reached The main arteries were well constructed: they were on foot. The nearest road was an hour’s walk away. paved with cobbles and buttressed by sustaining walls. Although the village was without electricity, a shuttle At many river crossings elegant stone bridges witness the service by donkey supplied the local kafeneíon with beer importance of the routes. Traditional country inns indicate and cola. the places where the traveller could rest and feed himself Since then, the bulldozer has moved on and connected and his animals. -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies. -

Euboea and Athens

Euboea and Athens Proceedings of a Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace Athens 26-27 June 2009 2011 Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece Publications de l’Institut canadien en Grèce No. 6 © The Canadian Institute in Greece / L’Institut canadien en Grèce 2011 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Euboea and Athens Colloquium in Memory of Malcolm B. Wallace (2009 : Athens, Greece) Euboea and Athens : proceedings of a colloquium in memory of Malcolm B. Wallace : Athens 26-27 June 2009 / David W. Rupp and Jonathan E. Tomlinson, editors. (Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece = Publications de l'Institut canadien en Grèce ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9737979-1-6 1. Euboea Island (Greece)--Antiquities. 2. Euboea Island (Greece)--Civilization. 3. Euboea Island (Greece)--History. 4. Athens (Greece)--Antiquities. 5. Athens (Greece)--Civilization. 6. Athens (Greece)--History. I. Wallace, Malcolm B. (Malcolm Barton), 1942-2008 II. Rupp, David W. (David William), 1944- III. Tomlinson, Jonathan E. (Jonathan Edward), 1967- IV. Canadian Institute in Greece V. Title. VI. Series: Publications of the Canadian Institute in Greece ; no. 6. DF261.E9E93 2011 938 C2011-903495-6 The Canadian Institute in Greece Dionysiou Aiginitou 7 GR-115 28 Athens, Greece www.cig-icg.gr THOMAS G. PALAIMA Euboea, Athens, Thebes and Kadmos: The Implications of the Linear B References 1 The Linear B documents contain a good number of references to Thebes, and theories about the status of Thebes among Mycenaean centers have been prominent in Mycenological scholarship over the last twenty years.2 Assumptions about the hegemony of Thebes in the Mycenaean palatial period, whether just in central Greece or over a still wider area, are used as the starting point for interpreting references to: a) Athens: There is only one reference to Athens on a possibly early tablet (Knossos V 52) as a toponym a-ta-na = Ἀθήνη in the singular, as in Hom.