Analogy and Sound Change in Ancient Greek Brian D. Joseph 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mycenaeans

THE MYCENAEANS The Mycenaean (my-suh-NEE-uhn) people arrived around 1600 b.c. around 1250 b.c. By the year 1000 b.c., They lived on the mainland of Greece. This was at the same time as the the Mycenaean civilization had totally height of the Minoan civilization on Crete. The Mycenaeans had small collapsed. kingdoms built high on hills. Each kingdom had a different ruler. The This collapse began a period in Greek rulers lived in palaces protected by stone walls. history known as the Dark Ages. This was The Mycenaeans were warriors. They were also great at trading a hard time for the Greeks. and crafts. Foreign invaders began to threaten Mycenaean kingdoms Lasting Poetry Ruins of a Mycenaean kingdom A man named Homer wrote two very famous stories. The stories are the epic poems the Iliad (IL-ee-uhd) and the Odyssey (AW-duh- see). They are believed to describe events in Mycenaean history. Old Food Mycenaeans probably ate the same foods that Greeks eat today. Bread, cheese, olives, figs, grapes, goat, and fish are common Greek foods. 8 9 CITY-STATES Around the eighth century b.c., the towns and countrysides of Greece began to grow. Greece was coming out of the Dark Ages. Military leaders and wealthy families ruled small areas. These were called poleis (PAW-lays), or city-states. Over the centuries most poleis developed democratic forms of rule. A typical city-state was These are the ruins of a marketplace in Athens. The Meaning of Democracy The word democracy means “rule by the people.” It comes from two ancient Greek words— Sparta was an important city-state. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Athens & Ancient Greece

##99668811 ATHENS & ANCIENT GREECE NEW DIMENSION/QUESTAR, 2001 Grade Levels: 9-13+ 30 minutes DESCRIPTION Recalls the historical significance of Athens, using modern technology to re-create the Acropolis and Parthenon theaters, the Agora, and other features. Briefly reviews its history, famous citizens, contributions, a typical day, and industries. ACADEMIC STANDARDS Subject Area: World History - Era 3 – Classical Traditions, Major Religions, and Giant Empires, 1000 BCE – 300 CE Standard: Understands how Aegean civilization emerged and how interrelations developed among peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean and Southwest Asia from 600 to 200 BCE • Benchmark: Understands the major cultural elements of Greek society (e.g., the major characteristics of Hellenic sculpture, architecture, and pottery and how they reflected or influenced social values and culture; characteristics of Classical Greek art and architecture and how they are reflected in modern art and architecture; Socrates' values and ideas as reflected in his trial; how Greek gods and goddesses represent non-human entities, and how gods, goddesses, and humans interact in Greek myths) (See Instructional Goals #3, 4, and 5.) • Benchmark: Understands the role of art, literature, and mythology in Greek society (e.g., major works of Greek drama and mythology and how they reveal ancient moral values and civic culture; how the arts and literature reflected cultural traditions in ancient Greece) (See Instructional Goal #4.) • Benchmark: Understands the legacy of Greek thought and government -

Herodotus' Four Markers of Greek Identity (Ch

Loyola Marymount University From the SelectedWorks of Katerina Zacharia September, 2008 Hellenisms (ii), Herodotus' Four Markers of Greek Identity (ch. 1) Katerina Zacharia, Loyola Marymount University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/katerina_zacharia/15/ 1. Herodotus’ Four Markers of Greek Identity Katerina Zacharia [...] πρὸς δὲ τοὺς ἀπὸ Σπάρτης ἀγγέλους τάδε· Τὸ μὲν δεῖσαι Λακεδαιμονίους μὴ ὁμολογήσωμεν τῷ βαρβάρῳ κάρτα ἀνθρωπήιον ἦν. ἀτὰρ αἰσχρῶς γε οἴκατε ἐξεπιστάμενοι τὸ Ἀθηναίων φρόνημα ἀρρωδῆσαι, ὅτι οὔτε χρυσός ἐστι γῆς οὐδαμόθι τοσοῦτος οὔτε χώρη καλλει καὶ ἀρετῇ μέγα ὑπερφέρουσα, τὰ ἡμεῖς δεξάμενοι ἐθέλοιμεν ἂν μηδίσαντες καταδουλῶσαι τὴν Ἑλλάδα. Πολλὰ τε γὰρ καὶ μεγαλα ἐστι τὰ διακωλύοντα ταῦτα μὴ ποιέειν μηδ᾿ ἢν ἐθέλωμεν, πρῶτα μὲν καὶ μέγιστα τῶν θεῶν τὰ ἀγάλματα καὶ τὰ οἰκήματα ἐμπεπρησμένα τε καὶ συγκεχωσμένα, τοῖσι ἡμέας ἀναγκαίως ἔχει τιμωρέειν ἐς τὰ μέγιστα μᾶλλον ἤ περ ὁμολογέειν τῷ ταῦτα ἐργασαμένῳ, αὖτις δὲ τὸ Ἑλληνικὸν, ἐὸν ὅμαιμόν τε καὶ ὁμόγλωσσον, καὶ θεῶν ἱδρύματά τε κοινὰ καὶ θυσίαι ἤθεά τε ὁμότροπα, τῶν προδότας γενέσθαι Ἀθηναίους οὐκ ἂν εὖ ἔχοι. ἐπίστασθέ τε οὕτω, εἰ μὴ καὶ πρότερον ἐτύγχανετε ἐπιστάμενοι, ἔστ᾿ ἂν καὶ εἶς περιῇ Ἀθηναίων, μηδαμὰ ὁμολογήσοντας ἡμέας Ξέρξῃ .1 Herodotus, Histories, 8, 144.1–3 1. The Sources: Some Qualifiers All contributors were invited to think about the four characteristic features of Hellenism (blood, language, religion, and customs) listed by some anonymous Athenian speakers at the end of Herodotus VIII, in the caption of this chapter. Some of the questions the contributors were asked to explore are: How far has it been true historically that these four features have acted 1 “To the Spartan envoys they said: ‘No doubt it was natural that the Lacedaemonians should dread the possibility of our making terms with Persia; none the less it shows a poor estimate of the spirit of Athens. -

Vocabulary in Robert Beekes's Etymological

Studia Linguistica Universitatis Iagellonicae Cracoviensis 133 (2016): 149–169 doi:10.4467/20834624SL.16.011.5680 FILIP DE DECKER Universiteit Gent [email protected] ETYMOLOGICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS ON THE ‹PG› AND ‹PG?› VOCABULARY IN ROBERT BEEKES’S ETYMOLOGICAL DICTIONARY OF GREEK: N Keywords: substrate, inherited lexicon, Indo-European phonology, Greek Abstract This article presents an etymological case study on Pre-Greek (PG): it analyzes about 20 words starting with the letter N that have been catalogued as ‹PG› or ‹PG?› in the new Etymological dictionary of Greek (EDG), but for which alternative explanations are equally possible or more likely. The article starts by discussing the Leiden etymological dictionaries series, then discusses the EDG and the concept of PG and then analyzes the individual words. This analysis is performed by giving an overview of the most important earlier suggestions and contrasting it with the arguments used to catalogue the word as PG. In the process, several issues of Indo-European phonology (such as the phoneme inventory and sound laws) will be discussed. 1. General observations on the EGD and the Leiden etymological dictionar- ies series1 The Leiden etymological dictionaries series intends to replace Pokorny (1959), no longer up-to-date in matters of phonology and morphology, by publishing separate etymo- logical dictionaries of every Indo-European language (Beekes 1998). While an update of Pokorny is necessary, some remarks need to be made. First, most etymological 1 For a (scathing) assessment of the Series, see Vine (2012) and Meissner (2014). For a detailed discussion of the EDG, the reader is referred to Meissner (2014). -

Ancient Greece

αρχαία Ελλάδα (Ancient Greece) The Birthplace of Western Civilization Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Unit Three AA * European Civilization • Neolithic Europe • Europe’s earliest farming communities developed in Greece and the Balkans around 6500 B.C. • Their staple crops of emmer wheat and barley were of near eastern origin, indicating that farming was introduced by settlers from Anatolia • Farming spread most rapidly through Mediterranean Europe. • Society was mostly composed of small, loose knit, extended family units or clans • They marked their territory through the construction of megalithic tombs and astronomical markers • Stonehenge in England • Hanobukten, Sweden * European Civilization • Neolithic Europe • Society was mostly composed of small, loose knit, extended family units or clans • These were usually built over several seasons on a part time basis, and required little organization • However, larger monuments such as Stonehenge are evidence of larger, more complex societies requiring the civic organization of a territorial chiefdom that could command labor and resources over a wide area. • Yet, even these relatively complex societies had no towns or cities, and were not literate * European Civilization • Ancient Aegean Civilization • Minos and the Minotaur. Helen of Troy. Odysseus and his Odyssey. These names, still famous today, bring to mind the glories of the Bronze Age Aegean. • But what was the truth behind these legends? • The Wine Dark Sea • In Greek Epic, the sea was always described as “wine dark”, a common appellation used by many Indo European peoples and languages. • It is even speculated that the color blue was not known at this time. Not because they could not see it, but because their society just had no word for it! • The Aegean Sea is the body of water which lays to the east of Greece, west of Turkey, and north of the island of Crete. -

The Riddle of Ancient Sparta: Unwrapping the Enigma

29 May 2018 The Riddle of Ancient Sparta: Unwrapping the Enigma PROFESSOR PAUL CARTLEDGE (Sir Winston) Churchill once famously referred to Soviet Russia as ‘a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma’. My title is a simplified version of that seemingly obscure remark. The point of contact and comparison between ancient Sparta and modern Soviet Russia is the nature of the evidence for them, and the way in which they have been imagined and represented, by outsiders. There was a myth - or mirage – of ancient Sparta, as there was of Soviet Russia: typically, the outsider who commented was both very ignorant and either wildly PRO or – as in Churchill’s case – wildly ANTI. There was no moderate, middle way. The ‘Spartan Tradition’ (Elizabeth Rawson) is alive and – well, ‘well’ to this day. To start us off, I give you a relatively gentle, deliberately inoffensive and very British example of the PRO myth, mirage, legend or tradition of ancient Sparta. In 2017 Terry’s of York confectioners would have been celebrating its 150th anniversary, had it not been taken over by Kraft in 1993. A long discontinued but still long cherished Terry’s line was their ‘Spartan’ assortment: hard-centre chocolates, naturally. Because the Spartans were the ultimate ancient warriors, uber-warriors, if you like. And their fearsome reputation on the battlefield had won them not just respect but fame – and not just in antiquity: think only of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE – and of the movie 300. But of course the Spartans were no mere chocolate box soldiers - they were the real thing, the hard men of ancient Greece. -

The Greek Alphabet Sight and Sounds of the Greek Letters (Module B) the Letters and Pronunciation of the Greek Alphabet 2 Phonology (Part 2)

The Greek Alphabet Sight and Sounds of the Greek Letters (Module B) The Letters and Pronunciation of the Greek Alphabet 2 Phonology (Part 2) Lesson Two Overview 2.0 Introduction, 2-1 2.1 Ten Similar Letters, 2-2 2.2 Six Deceptive Greek Letters, 2-4 2.3 Nine Different Greek Letters, 2-8 2.4 History of the Greek Alphabet, 2-13 Study Guide, 2-20 2.0 Introduction Lesson One introduced the twenty-four letters of the Greek alphabet. Lesson Two continues to present the building blocks for learning Greek phonics by merging vowels and consonants into syllables. Furthermore, this lesson underscores the similarities and dissimilarities between the Greek and English alphabetical letters and their phonemes. Almost without exception, introductory Greek grammars launch into grammar and vocabulary without first firmly grounding a student in the Greek phonemic system. This approach is appropriate if a teacher is present. However, it is little help for those who are “going at it alone,” or a small group who are learning NTGreek without the aid of a teacher’s pronunciation. This grammar’s introductory lessons go to great lengths to present a full-orbed pronunciation of the Erasmian Greek phonemic system. Those who are new to the Greek language without an instructor’s guidance will welcome this help, and it will prepare them to read Greek and not simply to translate it into their language. The phonic sounds of the Greek language are required to be carefully learned. A saturation of these sounds may be accomplished by using the accompanying MP3 audio files. -

Ancient Greek Faqs

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS CLASSICS.UNC.EDU ANCIENT GREEK FAQS Who studies Ancient Greek? What is it? The Greek language has been spoken and written in the Mediterranean region since about 1200 BCE. “Ancient” Greek refers to the early part of that long history – especially the approximately 1000-year period from the epic poetry of Homer into the early Christian centuries. Anyone interested in the cultures, history, religion, and literature of the Ancient Mediterranean may want to study Ancient Greek. Many students interested in philosophy, linguistics, archaeology, art history, and the literary humanities more generally also find Greek relevant to their studies. Does Ancient Greek satisfy the general education language requirement? Yes, you can take three semesters of Ancient Greek (GREK 101, 102, 203) to satisfy the UNC language requirement. What happens in Ancient Greek classes? Classes focus on the language itself, as a window on a fascinating culture very distant from our own. In the first two semesters you’ll learn about the basic grammatical structures of the ancient language and start to build a core vocabulary. In the third semester you’ll be reading original texts by writers like the philosopher Plato, the epic poet Homer, and the tragedian Euripides. In advanced classes you’ll read a variety of literary texts, from the historian Herodotus, to the lyric poet Sappho, to ancient Greek novels, and satires by Lucian. For a complete list of our course offerings in Ancient Greek, see the Academic Catalogue (catalog.unc.edu Courses A-Z Greek). How much homework will there be? Regular engagement is essential to acquiring a new language, and homework is assigned daily in ancient Greek. -

Ancient Greek Architecture Complete the Graphic Organizer As You Follow Along with the Presentation

Ancient Greek Architecture Complete the graphic organizer as you follow along with the presentation. Types of Greek Columns • Doric • Ionic • Corinthian Doric Doric columns are the most simple of the three types of columns. There are three main parts of the column: the capitol, the shaft, and the frieze. The capitol is the top of the column that is made up of a circle topped by a square. The shaft is the tall part of the column. The frieze is the area above the column that has simple patterns for decorations. Doric Columns - Example There are many examples of ancient Doric buildings. Perhaps the most famous one is the Parthenon in Athens. Many buildings constructed today borrow some parts of the Doric design. Ionic The main parts of Ionic columns are the shaft, the flutes, the capitol, and the base. The shafts of Ionic columns are shorter than Doric columns, which made them look more slender. The flutes were lines that were carved into the shaft from top to bottom. The bases are large and look like carved, stacked rings. The capitols have scroll designs on them. The Ionic columns are a little more decorative than the Doric. Ionic Columns - Example • The Temple of Athena Nike in Athens, shown here, is one of the most famous Ionic buildings in the world. It is located on the Acropolis, very close to the Parthenon. Corinthian The Corinthian column is the most decorative column and is the type most people like best. The Corinthian capitals have flowers and leaves below a small scroll. -

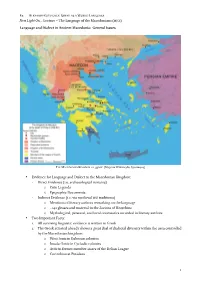

1 Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia

E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) Language and Dialect in Ancient Macedonia: General Issues THE MACEDONIAN KINGDOM CA. 336 BC (Map via Wikimedia Commons) • Evidence for Language and Dialect in the Macedonian Kingdom: - Direct Evidence (i.e. archaeological remains) o Coin Legends o Epigraphic Documents - Indirect Evidence (i.e. via medieval MSS traditions) o Mentions of literary authors remarking on the language o ~140 glosses and material in the Lexicon of Hesychius o Mythological, personal, and local onomastics recorded in literary authors • Two Important Facts: 1. All surviving linguistic evidence is written in Greek 2. The Greek attested already shows a great deal of dialectal diversity within the area controlled by the Macedonian kingdom: o West Ionic in Euboean colonies o Insular Ionic in Cycladic colonies o Attic in former member states of the Delian League o Corinthian at Potidaea 1 E2 — ALEXANDER’S LEGACY: GREEK AS A WORLD LANGUAGE New Light On… Lecture – The Language of the Macedonians (MJCS) o Attic-Ionic koiné in Macedonian official inscriptions Regarding the ‘Greekness’ of the Macedonians and their Language(s) • Evidence from literary sources is divided on the original ethnic and linguistic identity of the Ancient Macedonians: o Hesiod fr. 7: Eponymous ancestor Μακεδών born to Zeus and one of Deucalion’s daughters. o Herodotus (5.22, 8.137-139) strongly states a belief that Macedonians were Greeks o Thucydides (2.80.5-7, 2.81.6, 4.124.1) possibly considers Macedonians to be βάρβαροι. o Aristotle (1324b) includes Macedonians in a list of ἔθνη with despotic practices (ἐν τοῖς ἔθνεσι πᾶσι τοῖς δυναµένοις πλεονεκτεῖν), but makes no reference to language. -

The Case of Ancient Greek Literature Literary History Challenged Modern

This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by De Gruyter in the book “Griechische Literaturgeschichtsschreibung. Traditionen, Probleme und Konzepte” edited by J. Grethlein and A. Rengakos published in 2017. https://www.degruyter.com/view/product/469502 The research for this chapter has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement no. 312321 (AncNar). Literary History! The Case of Ancient Greek Literature Literary History Challenged Modern literary history emerged as part of Historicism. The acute awareness of the historical nature of human culture led to a strong interest in the development of literature, often of national literatures. The history of literature was envisaged as an organic process, as the expression of a people’s evolution.1 However, just as the tenets of Historicism lost their lustre, the idea of literary history started to draw fire. The critique can be traced back to the 19th century, but it gained force in the 20th century, so much force indeed that literature itself was declared “die Unmöglichkeitserklärung der Literaturgeschichtsschreibung“2. Nobody less prominent than René Wellek stated gloomily: “There is no progress, no development, no history of art except a history of writers, institutions and techniques. This is, at least for me, the end of an illusion, the fall of literary history.”3 One point that has been voiced by scholars from a wide range of proveniences is the idea that a historical approach is incapable of capturing the essence of literature. Wellek and Warren claimed: “Most leading histories of literature are either histories of civilization or collections of critical essays.