Gender and Politics of Identity in Sarala Devi's Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prelims Marathon JANUARY (FIRST WEEK), 2021

ForumIAS Prelims Marathon JANUARY (FIRST WEEK), 2021 HISTORY ECONOMICS POLITY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENT PRELIMS MARATHON COMPILATION FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY (FIRST WEEK), 2021 Freedom Struggle under Extremist Phase Q.1) Which of the following factors led to rise in militant nationalism in British India? 1. Recognition of the true nature of British Rule. 2. Growth of Self-confidence and Self-respect. 3. Growth of Education. Select the correct answer using the code given below: a) 1 only b) 1 and 2 only c) 2 and 3 only d) 1, 2 and 3 ANS: D Explanation: A radical trend of a militant nationalist approach to political activity started emerging in the 1890s and it took a concrete shape by 1905. As an adjunct to this trend, a revolutionary wing also took shape. Many factors contributed to the rise of militant nationalism: • Recognition of the true nature of British Rule. • Growth of Self-confidence and Self-respect. • Growth of Education. • International influences like Japan – Russia War. Source: Spectrum Modern India Page no, 288 – 289. Q.2) Arrange the following events in chronological order: 1. The Battle of Adwa. 2. The Boer wars. 3. The Japan – Russia War. Select the correct answer using the code given below: a) 1 – 2 – 3 b) 2 – 1 – 3 c) 3 – 1 – 2 d) 1 – 3 – 2 ANS: A Explanation: The defeat of the Italian army by Ethiopians (Battle of Adwa) (1896), the Boer wars (1899 - 1902) where the British faced reverses and Japan’s victory over Russia (1905) demolished myths of European invincibility. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

A Hundred Years of Tagore in Finland

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVII (2015) 10.12797/CIS.17.2015.17.08 Klaus Karttunen [email protected] (University of Helsinki) A Hundred Years of Tagore in Finland Summary: The reception of Rabindranath Tagore in Finland, starting from newspa- per articles in 1913. Finnish translations of his works (19 volumes in 1913–2013, some in several editions) listed and commented upon. Tagore’s plays in theatre, radio and TV, music composed on Tagore’s poems. Tagore’s poem (Apaghat 1929) commenting upon the Finnish Winter War. KEYWORDS: Rabindranath Tagore, Bengali Literature, Indian English Literature, Fin nish Literature. In Finland as well as elsewhere in the West, the knowledge of Indian literature was restricted to a few Sanskrit classics until the second decade of the 20th century. The Nobel Prize in Literature given to Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) in 1913 changed this at once. To some extent, the importance of Tagore had been noted even before—the Swedish Nobel Committee did not get his name out of nowhere.1 Tagore belonged to a renowned Bengali family and some echoes of this family had even been heard in Finland. As early as the 1840s, 1 The first version of this paper was read at the International Tagore Conference in Halle (Saale), Germany, August 2–3, 2012. My sincere thanks are due to Hannele Pohjanmies, the translator of Tagore’s poetry, who has also traced many details about the history of the poet in Finland. With her kind permission, I have used this material, supplementing it from newspaper archives and from my own knowledge. -

Jayadeva.Pdf

9 788126 001828 9 788126 001828 JAYADEVA As cover-design of this book on Jayadeva’s is reproduced a picture giving the faces of Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā, carved on a black marble slab from a drawing by Sri Dhirendra Krishna Deva Varma of Tripura. This is a work executed in 1935 by a modern Indian Artist, who is a pupil of Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, and who was Director of the Kalā-Bhavana at Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan School and Visva-Bharati University. The sculpture reproduced on the endpaper depicts a scene where three soothsayers are interpreting to King Śuddhodhana the dream of Queen Māyā, mother of Lord Buddha. Below them is seated a scribe recording the interpretation. This is perhaps the earliest available pictorial record of the art of writing in India. From: Nagarjunakonda, 2nd century A.D. Courtesy: National Museum, New Delhi MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE JAYADEVA SUNITI KUMAR CHATTERJI Sahitya Akademi Jayadeva: A monograph in English on Jayadeva, an eminent Indian philosopher and poet by Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi: 2017, ` 50. Sahitya Akademi Head Office Rabindra Bhavan, 35, Ferozeshah Road, New Delhi 110 001 Website: http://www.sahitya-akademi.gov.in Sales Office ‘Swati’, Mandir Marg, New Delhi 110 001 E-mail: [email protected] Regional Offices 172, Mumbai Marathi Grantha Sangrahalaya Marg, Dadar Mumbai 400 014 Central College Campus, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Veedhi Bengaluru 560 001 4, D.L. Khan Road, Kolkata 700 025 Chennai Office Main Guna Building Complex (second floor), 443, (304) Anna Salai, Teynampet, Chennai 600 018 © Sahitya Akademi First Published: 1973 Reprint: 1990, 1996, 2017 ISBN: 978-81-260-0182-8 Rs. -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Fill.- 6Diil ...•...T.N

fIlL.- 6DIil ...•...t.N. 1.[~1&JWw..a·~IUJ.NItIU ~-.~;;;;;_&~-=--~~~ 130 t'\_o.~e()r (~). r -lnl;c..""----------- Solo ;tpl~ . \ / ~------"""-""",,,,,,,,,~, -"'SERVANTS OF INDIA SOCIETY'S LIBRARY. POONA 4. FOR INTERN AL C[RCULATION To be returned on or before the last date stamped below 2,"~ HAY 19&8 2 3 MAY 1968 13 JAN 1913 t.rr: 15 FEB /973 .' -----~" INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JA VA. (Reproduced froIn the Sculptures of Botobudur.) fFrontisjlZ~ce . INDIAN ADVENTURERS SAILING OUT TO COLONIZE JAVA. (Reproduced from the Sculptures of Borob\ldur.) INDIAN SHIPPING A HISTORY OF THE SEA-BORNE TRADE AND MARITIME ACTIVITY OF THE INDIANS FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES BY RADHAKUMUD MOOKERJI, M.A. Prtm,Aattd RoyeAattd Stllllltw, Calnllta University H.""Aattd"" Basu Mallik ProfusOI" fI IndUut HIStory in IIze Natiotull. C-aJ fI Edwatiotf, Bengal WITH AN INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY BRAJENDRANATH SEAL, M.A., PH.D. hiwiJtll, AfdMtlja of C_j Bd.', CoIIqr, I ... LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. I, HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY 303, BOWBAZAR. STREET, CALCUTTA LONDON AND NEW YORK: X425" , ~odr ,/YlS E 2£..--- I?:> D f11ift o:n ~1ij<i\ii(9l1(f ~ ~ I \1 if: ~ if''''4If(11fElt: ~~ I II Do Thou Whose countenance is turned to all sides send oft' our adversaries, as if in a ship to the opposite shore: do Thou convey us in a ship across the sea for 9'!r welfare." [Ri,go-Yeda, I., 97, 7 fUld8.] PREFACE. ABOUT two years ago I submitted a thesis which was approved by the Carcutta University for my Premchand Roychand Studentship. It was sub sequently developed into the present work. -

Women and Indian Nationalism

Women and Indian Nationalism Leela Kasturi and Vina Mazumdar I The political role of women as a subject for research is of recent origin in India. 1 It is significant that there are so few studies of women's role in the nationalist movement or of the implications- social or political-of their momentous entry into the public sphere. Important works on the national movement mostly fail to examine the significance of women's participation in the struggles. 2 Analysis in this area so far has received insufficient attention in histories of India both before and after 1975 when the need to study women's role in history began to be acknowledged world-wide. One searches in vain for an adequate study of women's participation in nationalist historiography. 3 Studies published between 1968 and 1988 do touch upon various aspects and dimensions of women's participation in the national struggle for freedom. There are some factual accounts: most standard histories of the national movement mention women's entry into the Civil Disobedience Movement. 4 Some historians have noted the emancipatory effects of such participation. 5 Women in revolutionary terrorism have also been described 6 and women have been occasionally discussed as a political nuisance. 7 Some accounts of contemporaries who participated in the movement refer to the strength and broad base acquired by it as a whole through women's participation. 8 It is important to note that in general, information on women in the work of modern Indian historians writing in English prior to 1975 relates to women in elite sections of society. -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

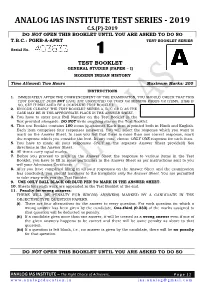

Analog Ias Institute Test Series - 2019 C.S.(P)-2019 Do Not Open This Booklet Until You Are Asked to Do So T.B.C.: Pgkb-A-Aprt Test Booklet Series

ANALOG IAS INSTITUTE TEST SERIES - 2019 C.S.(P)-2019 DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOKLET UNTIL YOU ARE ASKED TO DO SO T.B.C.: PGKB-A-APRT TEST BOOKLET SERIES Serial No. 1 TEST BOOKLET GENERAL STUDIES (PAPER – I) MODERN INDIAN HISTORY Time Allowed: Two Hours Maximum Marks: 200 INSTRUCTIONS 1. IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE EXAMINATION, YOU SHOULD CHECK THAT THIS TEST BOOKLET DOES NOT HAVE ANY UNPRINTED OR TORN OR MISSING PAGES OR ITEMS, ET(c) IF SO, GET IT REPLACED BY A COMPLETE TEST BOOKLET. 2. ENCODE CLEARLY THE TEST BOOKLET SERIES A, B, C OR D AS THE CASE MAY BE IN THE APPROPRIATE PLACE IN THE ANSWER SHEET. 3. You have to enter your Roll Number on the Test Booklet in the Box provided alongside. DO NOT write anything else on the Test Booklet. 4. This test Booklet contains 100 items (questions). Each item is printed both in Hindi and English. Each item comprises four responses (answers). You will select the response which you want to mark on the Answer Sheet. In case you feel that there is more than one correct response, mark the response which you consider the best. In any case, choose ONLY ONE response for each item. 5. You have to mark all your responses ONLY on the separate Answer Sheet provide(d) See directions in the Answer Sheet. 6. All items carry equal marks. 7. Before you proceed to mark in the Answer Sheet the response to various items in the Test Booklet, you have to fill in some particulars in the Answer Sheet as per instructions sent to you will your Admission Certificate. -

Mana Sanskriti (Our Culture)

VEPACHEDU EDUCATIONAL FOUNDATION మన సంసకృ逿 (MANA SANSKRITI) हमारी संकृ ति (HAMAAREE SANSKRTI) OUR CULTURE Home The Foundation Management The Andhra Journal of Industrial News The Telangana Science Journal Mana Sanskriti (Our Culture) Vegetarian Links Disclaimer Solicitation Contact VPC Vedah-Net ॐ भभू ुवभ ः वः तत्सववतभवुरेण्यम भर्गो देवय धीमवि। वधयो यो नः प्रचोदयात॥ Issue 254 Chief Editor: 萾呍ట쁍 శ్రీ ꀿవాస쀾푁 푇ప桇顁 | डॉ啍टर श्रीनिवासराव ु वेपचेद ु | Dr. Sreenivasarao Vepachedu |博士 斯瑞尼瓦萨饶 韦帕切杜 ROYALTY IN BOLLYWOOD Sachin Dev Burman was born on 1st October 1906 in Comilla, Bengal Presidency, present-day Bangladesh. His father was Nabadwipchandra Dev Burman, son of Maharaja Ishanachandra Manikya Dev Burman, Maharaja of Tripura. His mother was Raj Kumari Nirmala Devi, the royal princess of Manipur. SD Burman started working as a radio singer on Calcutta Radio Station in the late 1920s before commencing his musical journey in 1937 by composing songs for Bengali films. In 1944, Burman moved to Mumbai to score music for two films of superstar Ashok Kumar Shikari, Aat Din (1946) and Do Bhai (1947). Mera Sundar Sapna Beet Gaya sung by Geeta Dutt brought him fame. Burman embellished more than 100 films in Hindi and Bengali with his excellent music. His songs have been sung by all the established singers of the period such as Lata Mangeshkar, Asha Bhosle, Geeta Dutt, Shamshad Begum, Mohammed Rafi, Manna Dey, Kishore Kumar, Hemant Kumar, Mukesh, and Talat Mahmood. Rahul Dev Burman (aka Pancham)1 was born on 27 June 1939 and is the son of Sachin Dev Burman (above). -

C:\Users\Sadhan Chakrabarty\Desktop\060606.Xps

West Bengal Board of Secondary Education, Nivedita Bhaban, DJ-8, Sec : II, Karunamoyee, Salt Lake, Kolkata : 700091 HISTORY MODEL QUESTION (NEW SYLLABUS) TIME: 3 Hours 15 Minutes FULL MARKS: 90—For Regular Candidates ( First 15 minutes for reading the 100—For External Candidates question paper only ) Group: A 1. Choose the correct answer: [1x20=20] 1.1 The history of Calcutta Science College can be found in the— MCQ Model Answer: (a) History of photography (b) History of sports and games 1.1 (c) History of science and technology (c) History of science and technology (d) History of the environment 1.2 ‘Bangadarshan’ was first published in— (a) 1818 A.D (b) 1858 A.D. (c) 1872 A.D. (d) 1875 A.D. 1.3 The name that does not go with the spread of Western Education in India is— MCQ Model Answer: (a) Raja Rammohan Roy (c) Kaliprasanna Singha 1.3 (c) K aliprasanna (b) David Hare (d) Drinkwater Bethune Singha 1.4 The person known as ‘Brehmananda” was— (a) Debendranath Tagore (b) Radhakanta Deb (c) Keshab Chandra Sen (d) Shibnath Shastri 1.5 The ideals of ‘Sarva Dharma Samanyay’ was propagated by (a) Shibnath Shastri (b) Swami Vivekananda (c) Sri Ramakrishna (d) Raja Rammohan Roy 1.6 The Kol Rebellion (1831-32) took place in— (a) North Bengal (b) East Bengal (c) Chotanagpur (d) Bhagalpur 1.7 The Barasat revolt was led by— (a) Dudu Mian (b) Digambar Biswas (c) Titu Mir (d) Birsa Munda WBBSE Model Structure of Question Paper, MP (SE) 2017. West Bengal Board of Secondary Education, Nivedita Bhaban, DJ-8, Sec : II, Karunamoyee, Salt Lake, Kolkata : 700091 1.8 The first Viceroy of India appointed in accordance with the Queen’s Proclamation (1858) was— (a) Lord Dalhousie (b)Lord Canning (c) Lord Bentinck (d)Lord Mountbatten 1.9 The person associated with the activities of Indian Association was— (a) Keshab Chandra Sen (b) Surendranath Bandyopadhyay (c) Harish Chandra Mukhopadhyay (d) Gaganendranath Tagore 1.10 Find the odd one— (a) Bharatmata (b) Gora (c) Anandamath (d) Bartaman Bharat 1.11 U.