Dress As Metaphor in Diasporic Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prelims Marathon JANUARY (FIRST WEEK), 2021

ForumIAS Prelims Marathon JANUARY (FIRST WEEK), 2021 HISTORY ECONOMICS POLITY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY GEOGRAPHY AND ENVIRONMENT PRELIMS MARATHON COMPILATION FOR THE MONTH OF JANUARY (FIRST WEEK), 2021 Freedom Struggle under Extremist Phase Q.1) Which of the following factors led to rise in militant nationalism in British India? 1. Recognition of the true nature of British Rule. 2. Growth of Self-confidence and Self-respect. 3. Growth of Education. Select the correct answer using the code given below: a) 1 only b) 1 and 2 only c) 2 and 3 only d) 1, 2 and 3 ANS: D Explanation: A radical trend of a militant nationalist approach to political activity started emerging in the 1890s and it took a concrete shape by 1905. As an adjunct to this trend, a revolutionary wing also took shape. Many factors contributed to the rise of militant nationalism: • Recognition of the true nature of British Rule. • Growth of Self-confidence and Self-respect. • Growth of Education. • International influences like Japan – Russia War. Source: Spectrum Modern India Page no, 288 – 289. Q.2) Arrange the following events in chronological order: 1. The Battle of Adwa. 2. The Boer wars. 3. The Japan – Russia War. Select the correct answer using the code given below: a) 1 – 2 – 3 b) 2 – 1 – 3 c) 3 – 1 – 2 d) 1 – 3 – 2 ANS: A Explanation: The defeat of the Italian army by Ethiopians (Battle of Adwa) (1896), the Boer wars (1899 - 1902) where the British faced reverses and Japan’s victory over Russia (1905) demolished myths of European invincibility. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Women and Indian Nationalism

Women and Indian Nationalism Leela Kasturi and Vina Mazumdar I The political role of women as a subject for research is of recent origin in India. 1 It is significant that there are so few studies of women's role in the nationalist movement or of the implications- social or political-of their momentous entry into the public sphere. Important works on the national movement mostly fail to examine the significance of women's participation in the struggles. 2 Analysis in this area so far has received insufficient attention in histories of India both before and after 1975 when the need to study women's role in history began to be acknowledged world-wide. One searches in vain for an adequate study of women's participation in nationalist historiography. 3 Studies published between 1968 and 1988 do touch upon various aspects and dimensions of women's participation in the national struggle for freedom. There are some factual accounts: most standard histories of the national movement mention women's entry into the Civil Disobedience Movement. 4 Some historians have noted the emancipatory effects of such participation. 5 Women in revolutionary terrorism have also been described 6 and women have been occasionally discussed as a political nuisance. 7 Some accounts of contemporaries who participated in the movement refer to the strength and broad base acquired by it as a whole through women's participation. 8 It is important to note that in general, information on women in the work of modern Indian historians writing in English prior to 1975 relates to women in elite sections of society. -

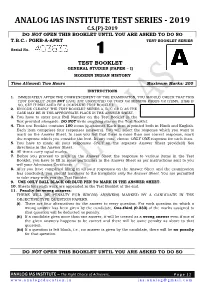

Analog Ias Institute Test Series - 2019 C.S.(P)-2019 Do Not Open This Booklet Until You Are Asked to Do So T.B.C.: Pgkb-A-Aprt Test Booklet Series

ANALOG IAS INSTITUTE TEST SERIES - 2019 C.S.(P)-2019 DO NOT OPEN THIS BOOKLET UNTIL YOU ARE ASKED TO DO SO T.B.C.: PGKB-A-APRT TEST BOOKLET SERIES Serial No. 1 TEST BOOKLET GENERAL STUDIES (PAPER – I) MODERN INDIAN HISTORY Time Allowed: Two Hours Maximum Marks: 200 INSTRUCTIONS 1. IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE EXAMINATION, YOU SHOULD CHECK THAT THIS TEST BOOKLET DOES NOT HAVE ANY UNPRINTED OR TORN OR MISSING PAGES OR ITEMS, ET(c) IF SO, GET IT REPLACED BY A COMPLETE TEST BOOKLET. 2. ENCODE CLEARLY THE TEST BOOKLET SERIES A, B, C OR D AS THE CASE MAY BE IN THE APPROPRIATE PLACE IN THE ANSWER SHEET. 3. You have to enter your Roll Number on the Test Booklet in the Box provided alongside. DO NOT write anything else on the Test Booklet. 4. This test Booklet contains 100 items (questions). Each item is printed both in Hindi and English. Each item comprises four responses (answers). You will select the response which you want to mark on the Answer Sheet. In case you feel that there is more than one correct response, mark the response which you consider the best. In any case, choose ONLY ONE response for each item. 5. You have to mark all your responses ONLY on the separate Answer Sheet provide(d) See directions in the Answer Sheet. 6. All items carry equal marks. 7. Before you proceed to mark in the Answer Sheet the response to various items in the Test Booklet, you have to fill in some particulars in the Answer Sheet as per instructions sent to you will your Admission Certificate. -

C:\Users\Sadhan Chakrabarty\Desktop\060606.Xps

West Bengal Board of Secondary Education, Nivedita Bhaban, DJ-8, Sec : II, Karunamoyee, Salt Lake, Kolkata : 700091 HISTORY MODEL QUESTION (NEW SYLLABUS) TIME: 3 Hours 15 Minutes FULL MARKS: 90—For Regular Candidates ( First 15 minutes for reading the 100—For External Candidates question paper only ) Group: A 1. Choose the correct answer: [1x20=20] 1.1 The history of Calcutta Science College can be found in the— MCQ Model Answer: (a) History of photography (b) History of sports and games 1.1 (c) History of science and technology (c) History of science and technology (d) History of the environment 1.2 ‘Bangadarshan’ was first published in— (a) 1818 A.D (b) 1858 A.D. (c) 1872 A.D. (d) 1875 A.D. 1.3 The name that does not go with the spread of Western Education in India is— MCQ Model Answer: (a) Raja Rammohan Roy (c) Kaliprasanna Singha 1.3 (c) K aliprasanna (b) David Hare (d) Drinkwater Bethune Singha 1.4 The person known as ‘Brehmananda” was— (a) Debendranath Tagore (b) Radhakanta Deb (c) Keshab Chandra Sen (d) Shibnath Shastri 1.5 The ideals of ‘Sarva Dharma Samanyay’ was propagated by (a) Shibnath Shastri (b) Swami Vivekananda (c) Sri Ramakrishna (d) Raja Rammohan Roy 1.6 The Kol Rebellion (1831-32) took place in— (a) North Bengal (b) East Bengal (c) Chotanagpur (d) Bhagalpur 1.7 The Barasat revolt was led by— (a) Dudu Mian (b) Digambar Biswas (c) Titu Mir (d) Birsa Munda WBBSE Model Structure of Question Paper, MP (SE) 2017. West Bengal Board of Secondary Education, Nivedita Bhaban, DJ-8, Sec : II, Karunamoyee, Salt Lake, Kolkata : 700091 1.8 The first Viceroy of India appointed in accordance with the Queen’s Proclamation (1858) was— (a) Lord Dalhousie (b)Lord Canning (c) Lord Bentinck (d)Lord Mountbatten 1.9 The person associated with the activities of Indian Association was— (a) Keshab Chandra Sen (b) Surendranath Bandyopadhyay (c) Harish Chandra Mukhopadhyay (d) Gaganendranath Tagore 1.10 Find the odd one— (a) Bharatmata (b) Gora (c) Anandamath (d) Bartaman Bharat 1.11 U. -

Volume9 Issue11(5)

Volume 9, Issue 11(5), November 2020 International Journal of Multidisciplinary Educational Research Published by Sucharitha Publications Visakhapatnam Andhra Pradesh – India Email: [email protected] Website: www.ijmer.in Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Dr.K. Victor Babu Associate Professor, Institute of Education Mettu University, Metu, Ethiopia EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Prof. S. Mahendra Dev Prof. Igor Kondrashin Vice Chancellor The Member of The Russian Philosophical Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Society Research, Mumbai The Russian Humanist Society and Expert of The UNESCO, Moscow, Russia Prof.Y.C. Simhadri Vice Chancellor, Patna University Dr. Zoran Vujisiæ Former Director Rector Institute of Constitutional and Parliamentary St. Gregory Nazianzen Orthodox Institute Studies, New Delhi & Universidad Rural de Guatemala, GT, U.S.A Formerly Vice Chancellor of Benaras Hindu University, Andhra University Nagarjuna University, Patna University Prof.U.Shameem Department of Zoology Prof. (Dr.) Sohan Raj Tater Andhra University Visakhapatnam Former Vice Chancellor Singhania University, Rajasthan Dr. N.V.S.Suryanarayana Dept. of Education, A.U. Campus Prof.R.Siva Prasadh Vizianagaram IASE Andhra University - Visakhapatnam Dr. Kameswara Sharma YVR Asst. Professor Dr.V.Venkateswarlu Dept. of Zoology Assistant Professor Sri.Venkateswara College, Delhi University, Dept. of Sociology & Social Work Delhi Acharya Nagarjuna University, Guntur I Ketut Donder Prof. P.D.Satya Paul Depasar State Institute of Hindu Dharma Department of Anthropology Indonesia Andhra University – Visakhapatnam Prof. Roger Wiemers Prof. Josef HÖCHTL Professor of Education Department of Political Economy Lipscomb University, Nashville, USA University of Vienna, Vienna & Ex. Member of the Austrian Parliament Dr.Kattagani Ravinder Austria Lecturer in Political Science Govt. Degree College Prof. -

The Political Emergence of Muslim Women in Bhopal, 1901-1930

Contesting Seclusion: The Political Emergence of Muslim Women in Bhopal, 1901-1930 Siobhan Lambert Hurley Submitted for the degree of Ph.D at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, May, 1998 ProQuest Number: 10673207 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673207 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Contesting Seclusion: The Political Emergence of Muslim Women in Bhopal, 1901-1930 This study examines the emergence of Indian Muslim women as politicians and social reformers in the early years of the twentieth century by focussing on the state of Bhopal, a small Muslim principality in Central India, which was ruled by a succession of female rulers throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The last Begam of Bhopal, Nawab Sultan Jahan Begam (1858-1930, r. 1901-1926), emerges as the main figure in this history, though a substantial effort has also been made to examine the activities of other Bhopali women, whether poor, privileged or princely. Special significance has been attached to their changing attitudes to class, gender and communal identities, using the veil as a metaphor for women’s expanding concerns. -

School Health Journal 11, November 2016.Cdr

The National Life Skills, Values Education & School Wellness Program Healthy Schools …… Healthy India Education is not preparation for life.. Education is life itself - John Dewey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Editorial Board i Editor’s Message ii Messages iii-iv Guidelines v “National Consultation on University and College Counselling Services in India”: Key Recommendations 1 Dr. Vikas Baniwal & Ms. Anshu Research Articles 9 Expression of Social Inclusion and Exclusion in Adolescent Friendships 10 Ms. Aakanksha Bhatia Educational Resilience: A Study of Students belonging to the Economically Weaker Section 17 Ms. Deepti Development of a Secular Identity in Religious Denomination Schools: A Case-Study Expressions India May-August 2016, Vol. 2, No. 3 EDITORS Prof. Namita Ranganathan Dr. Jitendra Nagpal Dr. Vikas Baniwal EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Kavita Sharma Brig. R. C Das Prof. J.L.Pandey Prof. Neerja Chadha Dr. Toolika Wadhwa Dr. Renu Malviya Dr. Poojashivam Jaitly Ms. Rita Chatterjee Ms. Astha Sharma Dr. Sharmila Majumdar Dr. Vandana Tara Dr. Neerja Chaddha Dr. Swastika Banerjee Dr. Naveen Raina Dr. Tulika Talwar Dr. Amiteshwar Ratra Ms. Saima Khan Dr Bharti Rajguru Ms. Manoranjini Dr. Ruchika Das ADVISORY BOARD Dr. H .K . Chopra Mrs. Amita Wattal Ms. Sudha Acharya Mrs. Kalpana Kapoor Dr. Divya S. Prasad Mr. Sanjay Bhartiya Dr. Geetesh Nirban Dr. Rajeev Seth Ms. Usha Anand Ms. Geetanjali Kumar Ms. Manjali Ganu Col. Jyoti Prakash Expressions India May-August 2016, Vol. 2, No. 3 EDITORS' MESSAGE Mental health concerns differ at different stages of the human development life-span and so do the ways in which these concerns and issues are experienced and dealt with. -

Western Women Who Supported the Indian Independence Movement

Neither Memsahibs nor Missionaries: Western Women who Supported the Indian Independence Movement by Sharon M. H. MacDonald B.A. with distinction, Mount Saint Vincent University, 1988 M.A. Atlantic Canada Studies, Saint Mary's University, 1999 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate Academic Unit of History, Faculty of Arts Supervisor: Gail Campbell, Ph.D., History Examining Board: Margaret Conrad, Ph.D., History, Chair Carey Watt, Ph.D., History Nancy Nason-Clark, Ph.D., Sociology External Examiner: Barbara Ramusack, Ph.D., History, University of Cincinnati This dissertation is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK March 2010 © Sharon M. H. MacDonald, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-82764-2 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-82764-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of The

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts CULTURE OF FOOD IN COLONIAL BENGAL A Dissertation in History by Utsa Ray © 2009 Utsa Ray Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 ii The dissertation of Utsa Ray was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mrinalini Sinha Liberal Arts Research Professor of History, Women’s Studies, and Asian Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Kumkum Chatterjee Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Joan B. Landes Ferree Professor of Early Modern History & Women’s Studies Nancy S. Love Director, Interdisciplinary Studies Program & Professor, Government and Justice Studies Appalachian State University Carol Reardon Director of Graduate Studies in History & Professor of Military History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii Abstract In “Culture of Food in Colonial Bengal ” I seek to relate the rise of a new middle- class in colonial Bengal to the development of a new gastronomic culture. I argue that the colonial transformation of the relations of production contextualized the cultural articulation of a new set of values, prejudices, and tastes for the Bengali Hindu middle- class. These cultural values, together with the political and economic conditions of colonialism, formed the habitus of this class. I investigate the historical specificities of this instance of class-formation through an exploration of the discursive and non- discursive social practices that went into the production of a new “Bengali” cuisine. Drawing on government proceedings, periodical literature, recipe books, and visual materials, I demonstrate that the Bengali Hindu middle-class created a new cuisine, one that reflects both an enthusiasm to partake of the pleasures of capitalist modernity and an anxiety about colonial rule. -

Islam in the Modern World

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 Islam in the Modern World This comprehensive introduction explores the landscape of contemporary Islam. Written by a distinguished team of scholars, it: • provides broad overviews of the developments, events, people and movements that have defi ned Islam in the three majority-Muslim regions; • traces the connections between traditional Islamic institutions and concerns, and their modern manifestations and transformations. How are medieval ideas, policies and practices refashioned to address modern circumstances? • investigates new themes and trends that are shaping the modern Muslim experience such as gender, fundamentalism, the media and secularization; • off ers case studies of Muslims and Islam in dynamic interaction with diff erent societies. Islam in the Modern World includes illustrations, summaries, discussion points and suggestions for further reading that will aid understanding and revision. Additional Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 resources are provided via the companion website: www.routledge.com/cw/kenney. Jeffrey T. Kenney is Professor of Religious Studies and University Professor at DePauw University, USA. Ebrahim Moosa is Professor of Religion and Islamic Studies in the Department of Religion at Duke University, USA. Religions in the Modern World Also available: Buddhism in the Modern World Edited by David L. McMahan Forthcoming: Hinduism in the Modern World Edited by Brian A. Hatcher Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 slam in the Modern World I Edited by Jeffrey T. Kenney and Ebrahim Moosa Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 First published in 2014 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Jeff rey T. -

Iasbaba 60 Days 2020: History Compilation Week 3 and 4

IASBABA 60 DAYS 2020: HISTORY COMPILATION WEEK 3 AND 4 IASBABA 1 IASBABA 60 DAYS 2020: HISTORY COMPILATION WEEK 3 AND 4 Q.1) Consider the following pairs: Organisation Leader 1. Madras Mahajan Sabha P Ananda Charlu 2. Bombay Presidency Association K T Telang 3. All India National Conference Anand Mohan Bose Which of the pairs given above are correctly matched? a) 1 and 2 only b) 3 only c) 2 and 3 only d) 1, 2 and 3 Q.1) Solution (d) Pair 1 Pair 2 Pair 3 Correct Correct Correct Madras Mahajan Sabha was Bombay Presidency The Indian National formed in 1884 by a group of Association was formed in Association also known as younger nationalists of 1885 by popularly called Indian Association was the Madras such as M brothers-in-law – first avowed nationalist Viraraghavachariar, G Pherozeshah Mehta, K T organization founded in Subramaniya Iyer and P Telang and Badruddin Tyabji. British India by Surendranath Ananda Charlu. Banerjee and Ananda Mohan Bose in 1876. Q.2) Consider the following statements: 1. The first meeting of the Indian National Congress was organized by W. C. Banarjee in Gokuldas Tejpal Sanskrit College of Bombay. 2. A resolution was passed in the first meeting of Congress demanding expansion of Indian Council of the Secretary of State for India to include Indians. Which of the statements given above is/are correct? a) 1 only IASBABA 2 IASBABA 60 DAYS 2020: HISTORY COMPILATION WEEK 3 AND 4 b) 2 only c) Both 1 and 2 d) Neither 1 nor 2 Q.2) Solution (d) Statement 1 Statement 2 Incorrect Incorrect The first meeting of the Indian National Total 9 resolutions were passed.