Inscriptions and Communication in Anglo-Saxon England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrows Against Mail Armour

Arrows against Mail Armour David Jones Introduction Historical accounts differ greatly in their description of the effectiveness of arrows against mail armour 1. This is to be expected, since mail was made in a wide range of ring diameters and wire gauges, from metal of varying quality and with different types of riveted closure. Mail could be worn over or under additional garments of linen, leather, wool or cotton. Such materials may give substantial protection, especially against arrows that do not have sharp-edged heads 2. Arrowheads varied in type and in the quality of metal. Archers, and their bows, had a very wide range of strengths and might shoot at mailed targets from long to close range. All of these factors might influence the arrow- stopping ability of the composite defensive system. This paper describes tests that were intended to probe some of these factors. However, they were limited in scope by practical considerations. Firstly, they were confined to commercially available components, which limited the study to rings made from 1.22 mm diameter mild steel wire. Secondly, the garment under the mail was represented only by multiple layers of woven linen, of the type that had already been tested for its defensive properties against arrows 2. Thirdly, my own limitations as an archer confined the tests to close range, so that I could hit the small samples of mail, and to a bow of 74 lb. draw weight. The Construction of Medieval Mail Some dated specimens from archaeological excavation show how mail of the 11th and earlier centuries was constructed 3, 4. -

Animality, Subjectivity, and Society in Anglo-Saxon England

IDENTIFYING WITH THE BEAST: ANIMALITY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIETY IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of English Language and Literature by Matthew E. Spears January 2017 © 2017 Matthew E. Spears IDENTIFYING WITH THE BEAST: ANIMALITY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIETY IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Matthew E. Spears, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2017 My dissertation reconsiders the formation of subjectivity in Anglo-Saxon England. It argues that the Anglo-Saxons used crossings of the human-animal divide to construct the subject and the performance of a social role. While the Anglo-Saxons defined the “human” as a form of life distinct from and superior to all other earthly creatures, they also considered most humans to be subjects-in-process, flawed, sinful beings in constant need of attention. The most exceptional humans had to be taught to interact with animals in ways that guarded the self and the community against sin, but the most loathsome acted like beasts in ways that endangered society. This blurring of the human-animal divide was therefore taxonomic, a move to naturalize human difference, elevate some members of society while excluding others from the community, and police the unruly and transgressive body. The discourse of species allowed Anglo-Saxon thinkers to depict these moves as inscribed into the workings of the natural world, ordained by the perfect design of God rather than a product of human artifice and thus fallible. “Identifying with the Beast” is informed by posthumanist theories of identity, which reject traditional notions of a unified, autonomous self and instead view subjectivity as fluid and creative, produced in the interaction of humans, animals, objects, and the environment. -

Read Book the Treasures from Sutton Hoo Kindle

THE TREASURES FROM SUTTON HOO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gareth Williams | 48 pages | 31 Dec 2011 | BRITISH MUSEUM PRESS | 9780714128252 | English | London, United Kingdom The Sutton Hoo ship burial (article) | Khan Academy In the decades since, Sutton Hoo has been studied in depth. For many scholars, one of the most exciting aspects of the Sutton Hoo burial is its similarity to that depicted in the Old English epic poem, Beowulf. The eponymous hero of this work is a Geat from modern-day Sweden, who comes to the aid of the Danish king. In the poem, composed in the eighth century, there is a description of the burial of one Scyld Scefing, an ancestor of the Danish royal family. According to the poem, Scyld is laid to rest in a boat, surrounded by treasures. Although there is almost certainly no direct link between the events described in Beowulf and the burial, the same world of traditions and ideas inspired them. In both cases there is a notion that death includes a journey to the hereafter and that the deceased must be interred with objects from the world of the living, such as weapons, money, drinking horns, and musical instruments. The burial at Sutton Hoo, like those of confirmed Viking burials, shows a well-developed notion of the afterlife. Who then was buried in the boat at Sutton Hoo? No body has yet been found—perhaps because the acidic soil long ago dissolved it, although scholars point out that human remains have been found elsewhere at the site. History Magazine. In a series of mounds at Sutton Hoo in England revealed their astounding contents: the remains of an Anglo-Saxon funerary ship and a huge cache of seventh-century royal treasure. -

Barbaric Splendour: the Use of Image Before and After Rome Comprises a Collection of Essays Comparing Late Iron Age and Early Medieval Art

Martin with Morrison (eds) Martin with Morrison Barbaric Splendour: the use of image before and after Rome comprises a collection of essays comparing late Iron Age and Early Medieval art. Though this is an unconventional approach, Barbaric Splendour there are obvious grounds for comparison. Images from both periods revel in complex compositions in which it is hard to distinguish figural elements from geometric patterns. Moreover, in both periods, images rarely stood alone and for their own sake. Instead, they decorated other forms of material culture, particularly items of personal adornment and The use of image weaponry. The key comparison, however, is the relationship of these images to those of Rome. Fundamentally, the book asks what making images meant on the fringe of an expanding or contracting empire, particularly as the art from both periods drew heavily before and after Rome from – but radically transformed – imperial imagery. Edited by Toby Martin currently works as a lecturer at Oxford University’s Department for Continuing Education, where he specialises in adult and online education. His research concentrates on theoretical and interpretative aspects of material culture in Early Medieval Europe. Toby Toby F. Martin with Wendy Morrison has also worked as a field archaeologist and project officer in the commercial archaeological sector and continues to work as a small finds specialist. Wendy Morrison currently works for the Chilterns Conservation Board managing the NLHF funded Beacons of the Past Hillforts project, the UK’s largest high-res archaeological LiDAR survey. She also is Senior Associate Tutor for Archaeology at the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education. -

The Coppergate Helmet Tweddle, Dominic Fornvännen 78, 105-112 Ingår I: Samla.Raa.Se the Coppergate Helmet

The Coppergate Helmet Tweddle, Dominic Fornvännen 78, 105-112 http://kulturarvsdata.se/raa/fornvannen/html/1983_105 Ingår i: samla.raa.se The Coppergate Helmet B v Dom i nic Tweddle Tweddle, D. 1983. The Coppergate helmet. (Hjälmen frän Coppergate i York.) Fornvännen 78. Stockholm. A helmet was discovered in 1982 during building works at Coppergate, York. The cap of the helmet is composed of eight individual piéces rivetted together. There are two hinged cheek piéces with brass edge bindings, and the neck was protected by a curtain of iron mail, (bund inside the helmet. The nasal is decorated with a pair of contronted animals with their rear quarters deve loping into interlace. Över the eye sockels are hatched brass eyebrows. At the junction of these is an animal head acting as terminal to a narrow field with half-round edge bindings forming the crest of the helmet. This is filled with a metal foil decorated in repoussé with an inscription in Latin. A second field filled with an identical inscription runs from ear to ear. Comparison of the script and decoration with Northumbrian manuscripts suggests a date in mid eighth century lor the helmet. Dominic Tweddle, York Archaotogical Trust, 47 Aldwark York YOI2BZ England. The Coppergate helmet was discovered in the brow band for the eyes. Between them 1982 during building works at 16—22 Cop there is a long nasal — a continuation of the pergate, York. It lay face down near the cor nose to nape band — expanding from the ner of a rectangular plank-lined feature which junction ol the eye holes to form two points, also contained a spearhead of seventh- one in each of the long edges, before tapering century or låter form, a wooden disc with live again. -

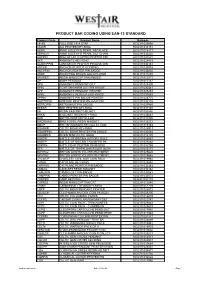

Product Bar Coding Using Ean-13 Standard

PRODUCT BAR CODING USING EAN-13 STANDARD Product Code Product Name Barcode 1914S FULL SIZE 1914 STAR 5032311025958 4X4KR 4x4 PEWTER KEY-RING 5032311033151 ABPN ANNE BOLEYN B PEARL NECKLACE 5032311018417 ABPNCH ANNE BOLEYN B PEARL GILT CHAIN 5032311032420 AHPPIN APACHE HELICOPTER PEWTER PIN 5032311031522 AKR AMMONITE KEY-RING 5032311025415 ALANCPPIN LANCASTER PEWTER PIN AVIATION 5032311032161 ANCKR ANCHOR PEWTER KEY-RING 5032311032918 ANCPPIN ANCHOR PEWTER PIN BADGE 5032311032802 ANSP ANOINTING SPOON GOLD PLATED 5032311011289 ANURES RESIN MINI EGYPTIAN ANUBIS 5032311012071 AP ANKH PENDANT 5032311012187 APG AMMONITE PENDANT GILT 5032311025309 APIN EGYPTIAN ANKH GILT PIN BADGE 5032311030341 APP AMMONITE PENDANT PEWTER 5032311025293 APPE AMMONITE PEWTER EAR-RINGS 5032311030853 APPIN AMMONITE PIN BADGE PEWTER 5032311028775 ASPITPPIN SPITFIRE PEWTER PIN AVIATION 5032311032178 ASTROPIN ASTRONAUT PIN BADGE 5032311027969 BEEKR BEE PEWTER KEY-RING 5032311031140 BH RESIN BASCINET HELMET 5032311032536 BHKR BASCINET RESIN KEY-RING 5032311033687 BHR BRITISH HISTORY RULER 5032311011005 BIRDFMAG BIRD FOSSIL RESIN MAGNET 5032311033212 BMCP BRITISH MONARCHS COLLECTION 5032311019148 BOARKR CELTIC BOAR KEY-RING 5032311024913 BOARPPIN CELTIC BOAR PEWTER PIN BADGE 5032311030464 BOARRES RESIN MINI CELTIC BOAR 5032311012170 BOBPR BATTLE OF BRITAIN HISTORY RULE 5032311026467 BOBTP BATTLE OF BRITAIN TRANSFER PK 5032311025248 BSPPIN BATTLESHIP PEWTER PIN BADGE 5032311032789 BTR BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR RULER 30CM 5032311015171 BWYPA2 BRITON WANTS YOU RECRUITMENT 5032311025620 -

Dyeing Sutton Hoo Nordic Blonde: an Interpretation of Swedish Influences on the East Anglian Gravesite

DYEING SUTTON HOO NORDIC BLONDE: AN INTERPRETATION OF SWEDISH INFLUENCES ON THE EAST ANGLIAN GRAVESITE Casandra Vasu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2008 Committee: Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Charles E. Kanwischer © 2008 Casandra Vasu All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Hershberger, Advisor Nearly seventy years have passed since the series of tumuli surrounding Edith Pretty’s estate at Sutton Hoo in Eastern Suffolk, England were first excavated, and the site, particularly the magnificent ship-burial and its associated pieces located in Mound 1, remains enigmatic to archaeologists and historians. Dated to approximately the early seventh century, the Sutton Hoo entombment retains its importance by illuminating a period of English history that straddles both myth and historical documentation. The burial also exists in a multicultural context, an era when Scandinavian influences factored heavily upon society in the British Isles, predominantly in the areas of art, religion and literature. Literary works such as the Old English epic of Beowulf, a tale of a Geatish hero and his Danish and Swedish counterparts, offer insight into the cultural background of the custom of ship-burial and the various accoutrements of Norse warrior society. Beowulf may hold an even more specific affinity with Sutton Hoo, in that a character from the tale, Weohstan, is considered to be an ancestor of the man commemorated in the ship- burial in Mound 1. Weohstan, whose allegiance lay with the Geats, was nonetheless a member of the Wægmunding clan, distant relations to the Swedish Scylfing dynasty. -

Leeds Studies in English

Leeds Studies in English Article: Gale R. Owen-Crocker, 'Anglo-Saxon Women: The Art of Concealment', Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 33 (2002), 31-51 Permanent URL: https://ludos.leeds.ac.uk:443/R/-?func=dbin-jump- full&object_id=123807&silo_library=GEN01 Leeds Studies in English School of English University of Leeds http://www.leeds.ac.uk/lse Anglo-Saxon Women: The Art of Concealment* Gale R. Owen-Crocker The tomb of the Anglo-Saxon saint, Cuthbert, which had remained behind the high altar in Durham Cathedral since the construction of the building in 1104, was excavated in 1827.1 St Cuthbert, a Northumbrian ascetic, had died in 687, but his shrine subsequently became a cult centre, and his coffin was opened on a number of occasions when relics were removed and precious gifts added.2 The nineteenth-century excavation revealed the remains of textiles which had encased the saint's body in ever- increasing layers of expensive shrouding over several hundred years of devotion. The most sumptuous were a silk stole and maniple, lavishly embroidered in coloured silks and spun gold (file thread made by winding a gold lamella round a silk core). These matching vestments have become landmarks in Art History and Textile History.3 The stole is embroidered on the front with elegant, full-length depictions of named Old Testament prophets flanking a central motif of the hand of God; busts of Thomas and James, saints of the extreme east and west, occupy the terminals. The maniple is decorated on the front with the figures of two popes and their deacons, again all named, and flanking the hand of God. -

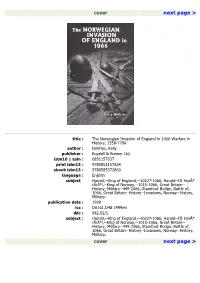

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title : The Norwegian Invasion of England in 1066 Warfare in History, 1358-779X author : DeVries, Kelly. publisher : Boydell & Brewer Ltd. isbn10 | asin : 0851157637 print isbn13 : 9780851157634 ebook isbn13 : 9780585372860 language : English subject Harold,--King of England,--1022?-1066, Harald--III Harð ráði,--King of Norway,--1015-1066, Great Britain-- History, Military--449-1066, Stamford Bridge, Battle of, 1066, Great Britain--History--Invasions, Norway--History, Military. publication date : 1999 lcc : DA161.D48 1999eb ddc : 942.02/1 subject : Harold,--King of England,--1022?-1066, Harald--III Harð ráði,--King of Norway,--1015-1066, Great Britain-- History, Military--449-1066, Stamford Bridge, Battle of, 1066, Great Britain--History--Invasions, Norway--History, Military. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i The Norwegian Invasion of England in 1066 Warfare in History < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_ii next page > Page ii Warfare in History General Editor: Matthew Bennett ISSN 1358779X Already published The Battle of Hastings: Sources and Interpretations edited and introduced by Stephen Morillo Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century: Discipline, Tactics, and Technology Kelly DeVries The Art of Warfare in Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from the Eighth Century to 1340 (second edition) J. F. Verbruggen Knights and Peasants: The Hundred Years War in the French Countryside Nicholas Wright Society at War: The Experience of England and France during the Hundred Years War edited by Christopher Allmand The Circle of War in the Middle Ages: Essays on Medieval Military and Naval History edited by Donald J. Kagay and L. -

The Symbolic Life of Birds in Anglo-Saxon England

The Symbolic Life of Birds in Anglo-Saxon England Janina Ramirez PhD Thesis 2006 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Contents i List of Illustrations iii Acknowledgements x Abstract xi List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Text and Image 3 Interdisciplinarity 4 Symbolic Life and Symbols 5 Theoretical Lenses 6 Semiotics 6 Iconography 7 Iconology 8 Reader Response 9 Parameters of Study 10 Date and Provenance 10 Bede’s Northumbria 12 Unifying Factors - Riddling 16 Overinterpretation and Misinterpretation 23 Chapter 1: The Symbolic Life of Doves in Anglo-Saxon England 25 Problems with identifying doves 28 Background to the dove’s symbolic life 31 Doves in Anglo-Saxon Art - The Codex Amiatinus 40 Doves in Anglo-Latin Literature 50 Doves in Hiberno-Latin Literature 53 Chapter 2: The Symbolic Life of Ravens in Anglo-Saxon England 61 Background to the raven’s symbolic life 63 The raven in Genesis 8:7 65 Bede and the Textual Recensions of Genesis 8:7 71 Bede and His Treatment of the Raven 73 Bede and the Cadaver Theory 75 Ravens as a Beast of Battle 78 Ravens, Paul and Anthony 81 Ravens and Saint Cuthbert 85 Chapter 3: The Symbolic Life of Eagles in Anglo-Saxon England 89 The Eagle as an Evangelist symbol in Patristic Literature 91 The Eagle as an Evangelist symbol in Anglo-Latin Literature 95 The Eagle’s Other Symbolic Meanings 98 ii The Eagle in Early Christian Art 101 The Eagle in Anglo-Saxon Art 104 The Eagle Alongside the Other Evangelist Symbols 111 Eagles in Eighth-Century Northumbria 112 The Eagles on the Ruthwell Cross 121 Chapter 4: The Symbolic -

Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York A.J. Mainman and N. S. H. Rogers the Archaeology of York

The Archaology of York The Small Finds 17/14 CRAFT, INDUSTRY AND EVERYDAY LIFE Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York A.J. Mainman and N. S. H. Rogers The Archaeology of York Volume 17: The Small Finds General Editor P.V. Addyman © York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research 2000 Published by Council for British Archaeology Bowes Morrell House 111 Walmgate York YO1 9WA The Archaeology of York Vol.17: The Small Finds Fasc.14: Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York 936.2’843 First published in print format 2000 ISBN 978-1 874454 52 6 e-book ISBN 1 902771 11 7 (softback) Cover design: Charlotte Bentley; photographs: Simon I. Hill FRPS (Scire- bröc) Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York By A.J. Mainman and N.S.H. Rogers Published for York Archaeological Trust by the 2000 Council for British Archaeology Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................2451 Archaeological Introductions to the Sites ..........................................................................................................2455 The Conservation and Identification of the Finds by J.A. Spriggs with contributions on the amber and jet by I. Panter ....................................................................................................................................................................2466 Craft and Industry ......................................................................................................................................................2475 -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A catalogue and re-evaluation of the Urnes style in England Owen, Olwyan Anne How to cite: Owen, Olwyan Anne (1979) A catalogue and re-evaluation of the Urnes style in England, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10298/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT The first part contains a study of the methodological approaches used in the analysis of the Urnes style, and they are subsequen• tly applied to the Urnes material in Scandinavia. The Scandinavian style is discussed in relation to the different objects and monu• ments on which it- appears, and a dating is attempted. Against this background, in part two the English material is discussed, accord• ing to the medium in which it is executed, and an English version of the style is defined.