Read Book the Treasures from Sutton Hoo Kindle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscriptions and Communication in Anglo-Saxon England

TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 1 Arrived at the end of what I always liked to call ‘my adventure in the Netherlands’, I realize that the people I would like to thank are so many that it will be impossible to name them all in this short preface. First of all, I would like to thank Dr. Marco Mostert for his constant supervision. His comments, always delivered with kindness and accuracy, have helped me in making this thesis a better work and me, I hope, a better student. I would also like to express my gratitude to Prof. Rolf Bremmer at Universiteit Leiden for his support. His unexpected invitation to see the Leiden Riddle and glossaries rekindled the interest in and fascination for Anglo-Saxon studies when weariness had overwhelmed me. His classes, always lively, and the passion he put on his work have been a real inspiration. And a heartfelt ‘thank you’ should also go to Prof. David Murray who with that ‘Hwaet!’ shouted in class when I was still studying at the Università degli Studi di Urbino, “Carlo Bo”, first led me in the path of Anglo-Saxon studies I have been following so far. I would also like to show my gratitude to all the professors and doctors who thought me courses and tutorials. I have learnt much and I received encouragement and motivation from each one of them. Also I do not want to forget the support I received from the librarians and secretaries of Universiteit Utrecht. However, these two years I spent in the Netherlands have been more than student-life. -

Arrows Against Mail Armour

Arrows against Mail Armour David Jones Introduction Historical accounts differ greatly in their description of the effectiveness of arrows against mail armour 1. This is to be expected, since mail was made in a wide range of ring diameters and wire gauges, from metal of varying quality and with different types of riveted closure. Mail could be worn over or under additional garments of linen, leather, wool or cotton. Such materials may give substantial protection, especially against arrows that do not have sharp-edged heads 2. Arrowheads varied in type and in the quality of metal. Archers, and their bows, had a very wide range of strengths and might shoot at mailed targets from long to close range. All of these factors might influence the arrow- stopping ability of the composite defensive system. This paper describes tests that were intended to probe some of these factors. However, they were limited in scope by practical considerations. Firstly, they were confined to commercially available components, which limited the study to rings made from 1.22 mm diameter mild steel wire. Secondly, the garment under the mail was represented only by multiple layers of woven linen, of the type that had already been tested for its defensive properties against arrows 2. Thirdly, my own limitations as an archer confined the tests to close range, so that I could hit the small samples of mail, and to a bow of 74 lb. draw weight. The Construction of Medieval Mail Some dated specimens from archaeological excavation show how mail of the 11th and earlier centuries was constructed 3, 4. -

Animality, Subjectivity, and Society in Anglo-Saxon England

IDENTIFYING WITH THE BEAST: ANIMALITY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIETY IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of English Language and Literature by Matthew E. Spears January 2017 © 2017 Matthew E. Spears IDENTIFYING WITH THE BEAST: ANIMALITY, SUBJECTIVITY, AND SOCIETY IN ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Matthew E. Spears, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2017 My dissertation reconsiders the formation of subjectivity in Anglo-Saxon England. It argues that the Anglo-Saxons used crossings of the human-animal divide to construct the subject and the performance of a social role. While the Anglo-Saxons defined the “human” as a form of life distinct from and superior to all other earthly creatures, they also considered most humans to be subjects-in-process, flawed, sinful beings in constant need of attention. The most exceptional humans had to be taught to interact with animals in ways that guarded the self and the community against sin, but the most loathsome acted like beasts in ways that endangered society. This blurring of the human-animal divide was therefore taxonomic, a move to naturalize human difference, elevate some members of society while excluding others from the community, and police the unruly and transgressive body. The discourse of species allowed Anglo-Saxon thinkers to depict these moves as inscribed into the workings of the natural world, ordained by the perfect design of God rather than a product of human artifice and thus fallible. “Identifying with the Beast” is informed by posthumanist theories of identity, which reject traditional notions of a unified, autonomous self and instead view subjectivity as fluid and creative, produced in the interaction of humans, animals, objects, and the environment. -

Barbaric Splendour: the Use of Image Before and After Rome Comprises a Collection of Essays Comparing Late Iron Age and Early Medieval Art

Martin with Morrison (eds) Martin with Morrison Barbaric Splendour: the use of image before and after Rome comprises a collection of essays comparing late Iron Age and Early Medieval art. Though this is an unconventional approach, Barbaric Splendour there are obvious grounds for comparison. Images from both periods revel in complex compositions in which it is hard to distinguish figural elements from geometric patterns. Moreover, in both periods, images rarely stood alone and for their own sake. Instead, they decorated other forms of material culture, particularly items of personal adornment and The use of image weaponry. The key comparison, however, is the relationship of these images to those of Rome. Fundamentally, the book asks what making images meant on the fringe of an expanding or contracting empire, particularly as the art from both periods drew heavily before and after Rome from – but radically transformed – imperial imagery. Edited by Toby Martin currently works as a lecturer at Oxford University’s Department for Continuing Education, where he specialises in adult and online education. His research concentrates on theoretical and interpretative aspects of material culture in Early Medieval Europe. Toby Toby F. Martin with Wendy Morrison has also worked as a field archaeologist and project officer in the commercial archaeological sector and continues to work as a small finds specialist. Wendy Morrison currently works for the Chilterns Conservation Board managing the NLHF funded Beacons of the Past Hillforts project, the UK’s largest high-res archaeological LiDAR survey. She also is Senior Associate Tutor for Archaeology at the Oxford University Department for Continuing Education. -

The Coppergate Helmet Tweddle, Dominic Fornvännen 78, 105-112 Ingår I: Samla.Raa.Se the Coppergate Helmet

The Coppergate Helmet Tweddle, Dominic Fornvännen 78, 105-112 http://kulturarvsdata.se/raa/fornvannen/html/1983_105 Ingår i: samla.raa.se The Coppergate Helmet B v Dom i nic Tweddle Tweddle, D. 1983. The Coppergate helmet. (Hjälmen frän Coppergate i York.) Fornvännen 78. Stockholm. A helmet was discovered in 1982 during building works at Coppergate, York. The cap of the helmet is composed of eight individual piéces rivetted together. There are two hinged cheek piéces with brass edge bindings, and the neck was protected by a curtain of iron mail, (bund inside the helmet. The nasal is decorated with a pair of contronted animals with their rear quarters deve loping into interlace. Över the eye sockels are hatched brass eyebrows. At the junction of these is an animal head acting as terminal to a narrow field with half-round edge bindings forming the crest of the helmet. This is filled with a metal foil decorated in repoussé with an inscription in Latin. A second field filled with an identical inscription runs from ear to ear. Comparison of the script and decoration with Northumbrian manuscripts suggests a date in mid eighth century lor the helmet. Dominic Tweddle, York Archaotogical Trust, 47 Aldwark York YOI2BZ England. The Coppergate helmet was discovered in the brow band for the eyes. Between them 1982 during building works at 16—22 Cop there is a long nasal — a continuation of the pergate, York. It lay face down near the cor nose to nape band — expanding from the ner of a rectangular plank-lined feature which junction ol the eye holes to form two points, also contained a spearhead of seventh- one in each of the long edges, before tapering century or låter form, a wooden disc with live again. -

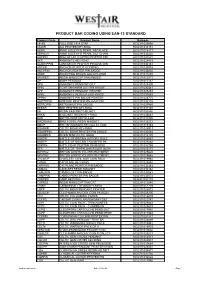

Product Bar Coding Using Ean-13 Standard

PRODUCT BAR CODING USING EAN-13 STANDARD Product Code Product Name Barcode 1914S FULL SIZE 1914 STAR 5032311025958 4X4KR 4x4 PEWTER KEY-RING 5032311033151 ABPN ANNE BOLEYN B PEARL NECKLACE 5032311018417 ABPNCH ANNE BOLEYN B PEARL GILT CHAIN 5032311032420 AHPPIN APACHE HELICOPTER PEWTER PIN 5032311031522 AKR AMMONITE KEY-RING 5032311025415 ALANCPPIN LANCASTER PEWTER PIN AVIATION 5032311032161 ANCKR ANCHOR PEWTER KEY-RING 5032311032918 ANCPPIN ANCHOR PEWTER PIN BADGE 5032311032802 ANSP ANOINTING SPOON GOLD PLATED 5032311011289 ANURES RESIN MINI EGYPTIAN ANUBIS 5032311012071 AP ANKH PENDANT 5032311012187 APG AMMONITE PENDANT GILT 5032311025309 APIN EGYPTIAN ANKH GILT PIN BADGE 5032311030341 APP AMMONITE PENDANT PEWTER 5032311025293 APPE AMMONITE PEWTER EAR-RINGS 5032311030853 APPIN AMMONITE PIN BADGE PEWTER 5032311028775 ASPITPPIN SPITFIRE PEWTER PIN AVIATION 5032311032178 ASTROPIN ASTRONAUT PIN BADGE 5032311027969 BEEKR BEE PEWTER KEY-RING 5032311031140 BH RESIN BASCINET HELMET 5032311032536 BHKR BASCINET RESIN KEY-RING 5032311033687 BHR BRITISH HISTORY RULER 5032311011005 BIRDFMAG BIRD FOSSIL RESIN MAGNET 5032311033212 BMCP BRITISH MONARCHS COLLECTION 5032311019148 BOARKR CELTIC BOAR KEY-RING 5032311024913 BOARPPIN CELTIC BOAR PEWTER PIN BADGE 5032311030464 BOARRES RESIN MINI CELTIC BOAR 5032311012170 BOBPR BATTLE OF BRITAIN HISTORY RULE 5032311026467 BOBTP BATTLE OF BRITAIN TRANSFER PK 5032311025248 BSPPIN BATTLESHIP PEWTER PIN BADGE 5032311032789 BTR BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR RULER 30CM 5032311015171 BWYPA2 BRITON WANTS YOU RECRUITMENT 5032311025620 -

Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York A.J. Mainman and N. S. H. Rogers the Archaeology of York

The Archaology of York The Small Finds 17/14 CRAFT, INDUSTRY AND EVERYDAY LIFE Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York A.J. Mainman and N. S. H. Rogers The Archaeology of York Volume 17: The Small Finds General Editor P.V. Addyman © York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research 2000 Published by Council for British Archaeology Bowes Morrell House 111 Walmgate York YO1 9WA The Archaeology of York Vol.17: The Small Finds Fasc.14: Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York 936.2’843 First published in print format 2000 ISBN 978-1 874454 52 6 e-book ISBN 1 902771 11 7 (softback) Cover design: Charlotte Bentley; photographs: Simon I. Hill FRPS (Scire- bröc) Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York By A.J. Mainman and N.S.H. Rogers Published for York Archaeological Trust by the 2000 Council for British Archaeology Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................2451 Archaeological Introductions to the Sites ..........................................................................................................2455 The Conservation and Identification of the Finds by J.A. Spriggs with contributions on the amber and jet by I. Panter ....................................................................................................................................................................2466 Craft and Industry ......................................................................................................................................................2475 -

The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare

zv i The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare This comprehensive volume provides easily accessible factual material on all major areas of warfare in the medieval west. The whole geographical area of medieval Europe, including eastern Europe, is covered, together with essential elements from outside Europe such as Byzantine warfare, nomadic horde invasions and the Crusades. The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare is presented in themed, illustrated sections, each preceded by a narrative outline offering a brief introduction. Within each section, Jim Bradbury presents clear information on battles and sieges, and generals and leaders. Readable and engaging, this detailed work makes use of archaeological information and includes clear discussions of controversial issues. The author examines practical topics including castle architecture, with descriptions of specific castles, shipbuilding techniques, improvements in armour, specific weapons, and developments in areas such as arms and armour, fortifications, tactics and supply. Jim Bradbury taught at a secondary school for ten years before becoming a senior lecturer and head of section for history at Borough Road College, now part of Brunel University. He has written widely on medieval history, with an emphasis on military history. zv i i This page intentionally left blank. zvi ii The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare JIM BRADBURY LONDON AND NEW YORK zv i v First published 2004 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. -

SMA 1998.Pdf

-y-efo-(A c r 1:41.0. SOUTH MIDLANDS ARCHAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUMBER 28, 1998 CONTENTS Page Editorial Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire 20 Northamptonshire 31 Oxfordshire 46 Publications 93 Reviews 93 Index 95 Notes for contributors 105 EDITOR: Barry Horne CHAIRMAN: Roy Friendship-Taylor 'Beaumont' Toad Hall Church End 86 Main Road Edlesborough Hackleton Dunstable, Beds Northampton LU6 2EP NN7 2AD HON SEC: Shelagh Lewis TREASURER: Jon Hitchcock Old College Farmhouse 75D Princes Street 2 Magdalen Close Dunstable Syresham Beds. Northants LU6 3AS NN13 5YF Typeset by Barry Home EDITORIAL The archaological picture in Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire continues in a state of flux. Buckinghamshire is a disaster area with little Museum or archaeology provision. Mike Farley has gone, the county is now only funding one post, the other is being funded on a short term basis by English Heritage. The archaeological provision in Milton Keynes has improved slightly but is still c,ausing the Group some concern. At the time of writing it looks as though the Bedford Archaeology Unit is to be externalised; in other words it is to sink or swim as best it can. You will see from the contents of this volume that lots of archaeology is going on in the Group's area. This is particularly so in Oxfordshire where a new vigorous group has started up in the north of the county. Regretably some groups who dig in the area have not submitted a report; this is particularly disappointing with regard to the gas pipeline which discovered many new sites as it cut through Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire during 1997. -

Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York 338.4’7685’0942843’0902

The Archaeology of York Volume 17: The Small Finds General Editor R.A. Hall © York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research 2003 Published by Council for British Archaeology Bowes Morrell House 111 Walmgate York YO1 9WA The Archaeology of York Vol.17: The Small Finds Fasc.16: Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York 338.4’7685’0942843’0902 First published in print format 2003 ISBN 1 902771 36 2 ISBN 978-1 874454 50 2 (e-book) Printed by Cover design: L. Collett Charlesworth Cover photography: M. Andrews Huddersfield W. Yorkshire Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Leather and Leatherworking in Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval York By Quita Mould, Ian Carlisle and Esther Cameron Published for York Archaeological Trust by the 2003 Council for British Archaeology Contents General Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................3185 Introduction to the sites and their dating by R.A. Hall, N.F. Pearson and R. Finlayson ........................................3187 The nature of the assemblages .....................................................................................................................................3203 Conservation of the Leatherwork by J.A. Spriggs .....................................................................................................3213 Craft and Industry .........................................................................................................................................................3222 -

Medieval Weapons: an Illustrated History of Their Impact

MEDIEVAL WEAPONS Other Titles in ABC-CLIO’s WEAPONS AND WARFARE SERIES Aircraft Carriers, Paul E. Fontenoy Ancient Weapons, James T. Chambers Artillery, Jeff Kinard Ballistic Missiles, Kev Darling Battleships, Stanley Sandler Cruisers and Battle Cruisers, Eric W. Osborne Destroyers, Eric W. Osborne Helicopters, Stanley S. McGowen Machine Guns, James H. Willbanks Military Aircraft in the Jet Age, Justin D. Murphy Military Aircraft, 1919–1945, Justin D. Murphy Military Aircraft, Origins to 1918, Justin D. Murphy Pistols, Jeff Kinard Rifles, David Westwood Submarines, Paul E. Fontenoy Tanks, Spencer C. Tucker MEDIEVAL WEAPONS AN ILLUSTRATED HISTORY OF THEIR IMPACT Kelly DeVries Robert D. Smith Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright 2007 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data DeVries, Kelly, 1956– Medieval weapons : an illustrated history of their impact / Kelly DeVries and Robert D. Smith. p. cm. — (Weapons and warfare series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-10: 1-85109-526-8 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-85109-531-4 (ebook) ISBN-13: 978-1-85109-526-1 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-85109-531-5 (ebook) 1. Military weapons—Europe—History—To 1500. 2. Military art and science—Europe—History—Medieval, 500-1500. I. Smith, Robert D. (Robert Douglas), 1954– II. -

The Latin Inscription on the Coppergate Helmet

134 NOTES zernalja I: 195-295. Sarajevo: Centar za Balka- Ph.D thesis, University of Freiburg. noloSka Ispitivanja, Akademija Nauka i RIEDEL,A. 1975. La fauna epipaleolitica della Grotta Umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine. Benussi (Trieste), in Atti e Mernorie Cornmis- 1981. KrSko podzemlje Istre kao prostor za nasel- sione E. Boegan. javanje fosilnih ljudi, Liburnijske terne 4: 119-35. SREJOVIC,D. 1974. The Odmut cave - a new facies of MARKOVIC,C. 1974. The stratigraphy and chronology the Mesolithic culture of the Balcan peninsula, of the cave Odrnut, Archaeologia Iugoslavica 15: Archaeologia Iugoslavica 15: 3-6. 7-1 1. TRINGHAM,R. 1971. Hunters, fishers and farmers of 1985. Neolit Crne Gore. Cetinje: Zavod za zaStitu eastern Europe 6000-3000 BC. London: Hut- spomenika kulture, SR Crne Gore. chinson. MAROVIC,I. 1979. Rezultati arheoloSkog sondiranja u TRUMP,D.H. 1980. Prehistory of the Mediterranean. Gospodskoj peCini kod vrela Cetine, Vjesnik za London: Allen Lane. arheologiju i historiju dalrnatinsku 72-3: 13-50. WHITEHOUSE,R.D. 1968. The early Neolithic of MULLER,J. 1988. Skarin Samograd - eine fruhneoli- southern Italy, Antiquity 42: 188-93. tische Station mit monochromer Ware und ZVELEBIL,M. (ed.) 1986. Hunters in transition. Cam- Impress0 Keramik an der Ostadria, Archaologi- bridge: Cambridge University Press. sches Korrespondenzblatt 1813: 219-35. ZVELEBIL,M. & P. ROWLEY-CONWY.1984. Transition to In press. Cultural definition and interaction of the farming in northern Europe: a hunter-gatherer eastern Adriatic early neolithic, Berytus 37. perspective, Norwegian Archaeological Review In prep. Das Fruhneolithikurn der ostlichen Adria. 1712: 104-28. The Latin inscription on the Coppergate helmet J.W.