A Dance Tor the Sun

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolic Role of Animals in the Plains Indian Sun Dance Elizabeth

17 The Symbolic Role of Animals in the Plains Indian Sun Dance 1 Elizabeth Atwood Lawrence TUFTS UNIVERSITY For many tribes of Plains Indians whose bison-hunting culture flourished during the 18th and 19th centuries, the sun dance was the major communal religious ceremony. Generally held in late spring or early summer, the rite celebrates renewal-the spiritual rebirth of participants and their relatives as well as the regeneration of the living earth with all its components. The sun dance reflects relationships with nature that are characteristic of the Plains ethos, and includes symbolic representations of various animal species, particularly the eagle and the buffalo, that once played vital roles in the lives of the people and are still endowed with sacredness and special powers. The ritual, involving sacrifice and supplication to insure harmony between all living beings, continues to be practiced by many contemporary native Americans. For many tribes of Plains Indians whose buffalo-hunting culture flowered during the 18th and 19th centuries, the sun dance was the major communal religious ceremony. Although details of the event differed in various groups, certain elements were common to most tribal traditions. Generally, the annual ceremony was held in late spring or early summer when people from different bands gathered together again following the dispersal that customarily took place in winter. The sun dance, a ritual of sacrifice performed by virtually all of the High Plains peoples, has been described among the Arapaho, Arikara, Assiniboin, Bannock, Blackfeet, Blood, Cheyenne, Plains Cree, Crow, Gros Ventre, Hidatsa, Kiowa, Mandans, Ojibway, Omaha, Ponca, Sarsi, Shoshone, Sioux (Dakota), and Ute (Spier, 1921, p. -

The Great Comanche Raid of 1840

SPECIAL EDITION AAGGAARRIITTAA GGAAZZEETTTTEE October 2011 A Chronicle of the Plum Creek Shooting Society Agarita Ranch Lockhart, Texas Marshals Range Marshal - Delta Raider TThhee BBaattttllee ooff PPlluumm CCrreeeekk Territorial Governor - Jake Paladin Safety Marshal - Elroy Rogers LONG JUAN Here!! Protest Marshal – Schuetzum Phast There will be no Plum Creek Shooting Society match the first Stage Marshal - Boon Doggle weekend in October. On the third weekend of October 2011 Long-Range Marshal - Wild Hog Administrative Marshal – Long Juan (10/14-16), we will host The Battle of Plum Creek, a cowboy Medical Marshal - Jake Paladin action shooting match at the Agarita Ranch near Lockhart, Texas. I Raffle Marshal – True Blue Cachoo had heard of the Battle of Plum Creek and read about it some in Costume Marshal - Lorelei Longshot the past, but did not know many details. I decided to investigate. Entertainment Marshal - Old Bill Dick What appears below is the result of what I found. I have noted Special Events Marshal - Belle Fire Side Match Marshal - Texas Sarge approximately where each stage of the match occurs and hope the Editor, Agarita Gazette – Long Juan story will make the match more fun for everyone. THE STORY BEHIND THE BATTLE OF PLUM CREEK INTRODUCTION In early August of 1840, under the light of a bright full moon, referred to by early Texas settlers as a Comanche moon, a war party of more than 600 Comanche and Kiowa warriors swept out of the Comancheria and rode for the heart of the Republic of Texas. The massive raid was launched in retaliation for what the Comanche perceived to be the unprovoked killing of twelve Penateka Comanche war chiefs and many Comanche women and children at the Council House peace talks in San Antonio the preceding March. -

Notes and Documents the Texas Frontier in 1850: Dr. Ebenezer Swift

Notes and Documents The Texas Frontier in 1850: Dr. Ebenezer Swift and the View From Fort Martin Scott by: CALEB COKER AND JANET G. HUMPHREY The Texas Frontier in 1850 was guarded by a line of army forts ranging from Fort Worth to Fort Duncan near Eagle Pass. With the end of the Mexican War, settlers had begun pushing toward the Texas interior, and troops became available to furnish new towns some measure of protection from raiding bands of Indians. 1 Fort Martin bScott, established between the towns of Fredericksburg and Zodiac in December 1848, was one such military post. The letter reproduced here, from the fort's physician, provides a marvelous glimpse of frontier Texas in 1850. It includes candid descriptions of a farm in Austin, life at the fort, and relationships with the local Indians. Native Americans living in the vicinity of Fort Martin Scott belonged to a number of tribes. The least predictable and most feared, however, were the Comanches. White settlements disrupted their wide-ranging lifestyle and threatened the abundant supply of game. In the mid-1840s their primary tactic was to attack settlers in small raiding parties and then vanish, often taking with them horses and other livestock. These hit-and-run assaults terrorized those on the frontier for decades.2 The Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas had purchased 10,000 acres of forested land just north of the Pedernales River on Barron's Creek in December 1845. By the following May, settlers began arriving from New Braunfels at the town site named Fredericksburg. -

Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Submitting, in Compliance with a Resolution of the Senate, an Estimate of the Amou

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 4-13-1860 Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, submitting, in compliance with a resolution of the Senate, an estimate of the amounts that will be required to hold councils with certain Indians of the plains and in the State of Minnesota. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Exec. Doc. No. 35, 36th Cong., 1st Sess. (1860) This Senate Executive Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 36TH CoNGRESs, ( SENATE. ~ Ex. Doc. 1st Session. ~ ( No. 35. REPORT OF THE COMMISSIONER OF INDIAN AFFAIRS, SUBMITTING, In compliance with a resolution of the Senate, an estimate of the mnounts that will be required to hold councils with certain Indians of the plains and in the State of Minnesota. APRIL 13, 1860.-Referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs. APRIL 16, 1860.-0rdered to be printed. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, Office Indian Affairs, April 12) 1860. SrR: In compliance with the request contained in a resolution of -

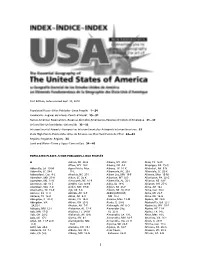

Download Index

First Edition, Index revised Sept. 23, 2010 Populated Places~Sitios Poblados~Lieux Peuplés 1—24 Landmarks~Lugares de Interés~Points d’Intérêt 25—31 Native American Reservations~Reservas de Indios Americanos~Réserves d’Indiens d’Améreque 31—32 Universities~Universidades~Universités 32—33 Intercontinental Airports~Aeropuertos Intercontinentales~Aéroports Intercontinentaux 33 State High Points~Puntos Mas Altos de Estados~Les Plus Haut Points de l’État 33—34 Regions~Regiones~Régions 34 Land and Water~Tierra y Agua~Terre et Eau 34—40 POPULATED PLACES~SITIOS POBLADOS~LIEUX PEUPLÉS A Adrian, MI 23-G Albany, NY 29-F Alice, TX 16-N Afton, WY 10-F Albany, OR 4-E Aliquippa, PA 25-G Abbeville, LA 19-M Agua Prieta, Mex Albany, TX 16-K Allakaket, AK 9-N Abbeville, SC 24-J 11-L Albemarle, NC 25-J Allendale, SC 25-K Abbotsford, Can 4-C Ahoskie, NC 27-I Albert Lea, MN 19-F Allende, Mex 15-M Aberdeen, MD 27-H Aiken, SC 25-K Alberton, MT 8-D Allentown, PA 28-G Aberdeen, MS 21-K Ainsworth, NE 16-F Albertville, AL 22-J Alliance, NE 14-F Aberdeen, SD 16-E Airdrie, Can 8,9-B Albia, IA 19-G Alliance, OH 25-G Aberdeen, WA 4-D Aitkin, MN 19-D Albion, MI 23-F Alma, AR 18-J Abernathy, TX 15-K Ajo, AZ 9-K Albion, NE 16,17-G Alma, Can 30-C Abilene, KS 17-H Akhiok, AK 9-P ALBUQUERQUE, Alma, MI 23-F Abilene, TX 16-K Akiak, AK 8-O NM 12-J Alma, NE 16-G Abingdon, IL 20-G Akron, CO 14-G Aldama, Mex 13-M Alpena, MI 24-E Abingdon, VA Akron, OH 25-G Aledo, IL 20-G Alpharetta, GA 23-J 24,25-I Akutan, AK 7-P Aleknagik, AK 8-O Alpine Jct, WY 10-F Abiquiu, NM 12-I Alabaster, -

In the Senate of the United States. Message from the President of the United States, Transmitting a Memorial of Certain Indian I

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 2-26-1892 In the Senate of the United States. Message from the President of the United States, transmitting a memorial of certain Indian in Oklahoma Territory relative to their claims to the lands they occupy. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation S. Exec. Doc. No. 46, 52nd Cong., 1st Sess. (1892) This Senate Executive Document is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 52D CONGRESS, } SENATE. Ex. Doc. 1st Se8.~ion. { No. 46. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES. MESSAG-E FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, TRANSMITTING A memorial of certain Indians in Oklahoma Te1'ritory 1·elative to their claims to the lands they occupy. FEBRUARY 26, 1892.-Read, referred to the Committee on Indian Affairs, and ordered to be printed. To the Sena.te and House of Representati'nes: I transmit herewith copy of a memorial of the Wichitas, Cnddoes, · and affiliated tribes of Indians in Oklal1oma Territory, in the matter of their claim to the lawls they occupy, for consideration in connection with the agreement concluded by and between tlte Cherokee Commission and said Indians, and also with my communiea tion of the 17th instant, relative to the act to pay the Uhoctaw and Uhickasaw Indians for certain lands now occupied by the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. -

Accepted Version

Article Discourses of Frontier Violence and the Trauma of National Emergence: Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove Quartet MADSEN, Deborah Lea Abstract In McMurtry’s fiction and in westerns as a genre, the rhetoric of American exceptionalism, of America’s special destiny in the world, serves to mythologize frontier violence and the trauma experienced by the victims of this physical, sexual and psychological violence, in order to sustain a conservative racial politics. McMurtry’s westerns present us with a late twentieth-century repetition of the rewriting of traumatic frontier stories in order to reinforce inherited concepts of American and non-American identities. These narratives continue to preserve the image of the frontier as a contact zone where a primitive multiculturalism gave rise to pathological mixed-blood individuals who, neither Mexican, Native, nor Anglo, are doomed to inhabit a liminal space that is nowhere and everywhere. Reference MADSEN, Deborah Lea. Discourses of Frontier Violence and the Trauma of National Emergence: Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove Quartet. Canadian Review of American Studies, 2009, vol. 39, no. 2, p. 185-204 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:87890 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 1 Published in Canadian Review of American Studies, special issue: Popular Westerns: New Scholarship, 39. 2 (2009), pp. 185-204. Discourses of Frontier Violence and the Trauma of National Emergence: Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove Quartet Deborah L. Madsen One of the most difficult aspects of reading Larry McMurtry’s otherwise eminently readable Lonesome Dove novels is his depiction of acts of extreme violence. -

Comanche Timeline

Comanche Timeline 1500 Comanches separate from Eastern Shoshone near Wind River. 1540 Coronado Expedition into the Southern Plains. 1540 Comanches known to be using dogs for transport. 1598 Spain builds colony in New Mexico and starts enslaving Indians. 1601 Don Juan de Onate encounters Plains Apache at Canadian River while looking for the Seven Cities of Gold (Cibola). 1680 Pueblo Rebellion, Comanches obtain horses. 1687 Sieur do La Sill encounters Comanches near Trinity River. 1692 Picuris relocates with Plains Apache in West Kansas. 1700 Comanches and Utes trade at Taos, New Mexico. 1706 Picuris returns to the Rio Grande Valley Area. 1716 Jicarilla Apache forced into mountains of New Mexico by repeated Comanche and Ute raids. 1716 During summer, Comanches and Utes trade at villages in New Mexico. 1716 Spanish attack Comanche/Ute Village north of Santa Fe; prisoners were taken and sold as slaves. 1719 First recorded Comanche raids in New Mexico for horses. 1719 Spanish send soldiers as far north as Pueblo, Colorado, only to find abandoned campsites. 1720 Apache bands retreat into Mexico from repeated Comanche attacks. 1720 Spanish send military expedition to investigate rumors of French trade and are destroyed by the Pawnee. 1723 War between Comanches and Utes and Plains Apache explode, two military expeditions sent to help the Apaches fail to locate Comanche and Ute Tribes. 1724 Comanche fight a nine-day war at Great Mountain of Iron, it results in major defeat for the Apache. 1724 French Trader Bourgmont trades with Padoucah in Kansas. 1725 Last Apaches settle on upper Arkansas River and disappeared. -

The Government of Texas and Her Indian Allies, 1836 - 1867

IN JUSTICE TO OUR INDIAN ALLIES: THE GOVERNMENT OF TEXAS AND HER INDIAN ALLIES, 1836-1867 William C. Yancey, B.A., M.S. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2008 APPROVED: Richard B. McCaslin, Major Professor Richard G. Lowe, Committee Member F. Todd Smith, Committee Member Adrian R. Lewis, Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Yancey, William C., In justice to our Indian allies: The government of Texas and her Indian allies, 1836 - 1867. Master of Arts (History), August 2008, 151 pp., 1 map, references, 65 titles. Traditional histories of the Texas frontier overlook a crucial component: efforts to defend Texas against Indians would have been far less successful without the contributions of Indian allies. The government of Texas tended to use smaller, nomadic bands such as the Lipan Apaches and Tonkawas as military allies. Immigrant Indian tribes such as the Shawnee and Delaware were employed primarily as scouts and interpreters. Texas, as a result of the terms of her annexation, retained a more control over Indian policy than other states. Texas also had a larger unsettled frontier region than other states. This necessitated the use of Indian allies in fighting and negotiating with hostile Indians, as well as scouting for Ranger and Army expeditions. Copyright 2008 by William C. Yancey ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROLOGUE.................................................................................................................... 1 Chapters 1. THE LIPAN APACHE AND TONKAWA INDIAN ALLIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS, 1836-1845.............................................................................. 8 2. THE IMMIGRANT INDIAN ALLIES OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS, 1836- 1845........................................................................................................ -

Indian Affairs at St

UNITED STATES-SOUTHERN PliAlNS IN )IAK REUTIO^:^j 1865-1868 by AVOHLEE FENTRESS ENGLISH, B.A. A THESIS IN HISTORY Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Technological College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER a? ARTS Approved May, 1962 f ACKNa\^L5DGMENTS I am deeply indebted to Dr. Ernest V/allace for his Invaluable assistance as thesis director and to Dr. David Vigness and Dr. Everett A. Oillis for their suggestions in writing the paper. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLSDCmSNTS 11 I. INTRODUCTION I RELATIONS BEFORE I865 • . 1 II. THE TREATIES OF THE LITTLE ARKANSAS ... 13 III, THE INVESTIGATION PERIOD 59 X\r. THE TREATIES OF MEDICINE LOD(ffi CREEK ... 8I V. PEACE AT LAST 132 BIBLIOGRAPHY , l4l ill CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: RELATIONS BEFORE 1865 The close of the Civil War marked a new era in the developmsnt of the American West. The relentless conquering spirit of the new nation had incited settlement to the Miaalaalppl River, which, after Jumping the Plains, developed along the Pacific coast. A sudden burst of expansionism into the undeveloped area at the end of battle was to be ex pected. The broad Great Plains, ruled coo^letely by nature's will, still remained in possession of the Indians. When migration over the old and the newly-developing traila aharply Increaaed and settlers moved onto the Plains, the tribes retaliated with devastating force. A bitter and long- laatlng struggle ensued to determine who would gain undis puted possession of the territory. Althoiigh the conflict lasted many years, the Imn^dlate events from I865 to I868 marked the termination of the reign of the powerful tribes' on the laat frontier. -

“Paha Sapa” – American Indian Use of the Black Hills May 16, 2007 Transcript

“Paha Sapa” – American Indian Use of the Black Hills May 16, 2007 Transcript SOUND: Donovin Sprague: I’m really happy that the Black Hills National Forest Advisory Board has asked me to present this information today. A lot of this pertains to the Lakota and American Indian history [and] use of this area – the black hills and surrounding regions. I wanted to start clear back in the 1780s. At that time, Congress declared that American Indian tribes were domestic and dependent nations. Domestic in that they were not foreign, so they were here. And then dependent – in this case that’s been interpreted to be on the U.S. government. So the U.S. government is really the entity that we work with and that’s the smoothest area if you can find that mode. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of things that happen with other entities (state and tribal) and sometimes those relationships are not developed in a conducive way that help people. So the U.S. government – that’s who we report to. This was affirmed by Justice John Marshall in a court case as well - Cherokee Nation vs. Georgia. The tribal law also comes into play with all this. But during that particular time period, I could refer to a lot of different books about this story, but the story that I am going to tell you is all from my own people and my family and what they were doing here at this time. So at that particular time, my great-great-great- grandfathers were being born. -

Table of Contents

Buffalo & the Plains Indians South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………… 1 Goals & Materials………………………………… 2 Teacher Resource Information……………........ 3-6 Erasing Native American Stereotypes……........ 7-9 Worksheets Word Find……………………………………........ 10 Word Find Key………………………………........ 11 Crossword Puzzle………………………………... 12 Crossword Puzzle Key…………………………... 13 Buffalo Uses Word Scramble………………....... 14 Word Scramble Key……………………………… 15 Buffalo Dot-to-Dot………………………………... 16 Activities Learning From Objects………………………….. 17-18 Object Identification List……………………... 19-21 Buffalo Hunt: Comparing Images…………........ 22-23 Where Do the Bones Fit? ................................. 24-26 How Many Jackrabbits Equal One Buffalo? ….. 27-31 How Big is a Buffalo? …………………………… 32 Buffalo Fractions…………………………………. 33-35 The Journey………………………………………. 36-39 Catching the Prey………………………………... 40-41 Making a Winter Count………………………….. 42-48 Quill Decorating………………………………….. 49 Pebble Patterns………………………………….. 50 1 Buffalo & the Plains Indians South Dakota State Historical Society Education Kit Goals and Materials GOALS Kit users will: acquire knowledge about how the Plains Indians used the buffalo. gain an understanding of people and animals living in a natural setting. develop skills in getting information from objects. MATERIALS This kit contains: Atlatl 2 Buffalo track molds Bladder Buffalo scat Scapula (shoulder blade bone) Arrow Horn spoon Awl Rawhide Sinew Parfleche (rawhide container) Hair rope Tail Buffalo robe