The Conflict in Upper Nile State Describes Events Through 9 April 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNMISS “Protection of Civilians” (Poc) Sites

UNMISS “Protection of Civilians” (PoC) Sites As of 9 April, the estimated number of civilians seeking safety in six Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites located on UNMISS bases is 117,604 including 52,908 in Bentiu, 34,420 in Juba UN House, 26,596 in Malakal, 2,374 in Bor, 944 in Melut and 362 in Wau. Number of civilians seeking protection STATE LOCATION Central UN House PoC I, II and III 34,420 Equatoria Juba Jonglei Bor 2,374 Upper Nile Malakal 26,596 Melut 944 Unity Bentiu 52,908 Western Bahr Wau 362 El Ghazal TOTAL 117,604 Activities in Protection Sites Juba, UN House The refugee agency in collaboration with the South Sudanese Commission for Refugee Affairs will be looking into issuing Asylum seeker certificates to around 500 foreign nationals at UN House PoC Site from 9 to 15 April. ADDITIONAL LINKS CLICK THE LINKS WEBSITE UNMISS accommodating 4,500 new IDPS in Malakal http://bit.ly/1JD4C4E Children immunized against measles in Bentiu http://bit.ly/1O63Ain Education needs peace, UNICEF Ambassador says in Yambio http://bit.ly/1CH51wX Food coming through Sudan helping hundreds of thousands http://bit.ly/1FBHHmw PHOTO UN Photo http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627829.html http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627828.html http://www.unmultimedia.org/s/photo/detail/627/0627831.html UNMISS facebook albums: https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.817801171628889.1073742395.160839527325060&type=3 https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.818162894926050.1073742396.160839527325060&type=3 UNMISS flickr album: -

EOI Mission Template

United Nations Nations Unies United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) South Sudan REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) This notice is placed on behalf of UNMISS. United Nations Procurement Division (UNPD) cannot provide any warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of contents of furnished information; and is unable to answer any enquiries regarding this EOI. You are therefore requested to direct all your queries to United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) using the fax number or e-mail address provided below. Title of the EOI: Provision of Refrigerant Gases to UNMISS in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan Date of this EOI: 10 January 2020 Closing Date for Receipt of EOI: 11 February 2020 EOI Number: EOIUNMISS17098 Chief Procurement Officer Unmiss Hq, Tomping Site Near Juba Address EOI response by fax or e-mail to the Attention of: International Airport, Room No 3c/02 Juba, Republic Of South Sudan Fax Number: N/A E-mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] UNSPSC Code: 24131513 DESCRIPTION OF REQUIREMENTS PD/EOI/MISSION v2018-01 1. The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) has a requirement for the provision of Refrigerant Gases in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan and hereby solicits Expression of Interest (EOI) from qualified and interested vendors. SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS / INFORMATION (IF ANY) Conditions: 2. Interested service providers/companies are invited to submit their EOIs for consideration by email (preferred), courier or by hand delivery as indicated below. -

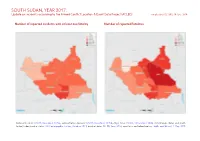

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, June 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 604 300 3351 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 404 299 1348 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 2 Strategic developments 120 0 0 Riots/protests 46 1 3 Methodology 3 Remote violence 25 3 17 Conflict incidents per province 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1200 603 4719 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). 2 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Methodology an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province is known. -

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

1 Covid-19 Weekly Situation

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH (MOH) PUBLIC HEALTHPUBLIC EMERGENCY HEALTH EMERGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATIONS CENTRE (PHEOC) CENTRE (PHEOC) COVID-19 WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Issue NO: 33 Reporting Period: 12-18 October 2020 (week 42) 36,740 2,655 CUMULATIVE SAMPLES TESTED CUMULATIVE RECOVERIES 2,847 CUMULATIVE CONFIRMED CASES 55 9,152 CUMULATIVE DEATHS CUMULATIVE CONTACTS LISTED FOR FOLLOW UP 1. KEY HIGHLIGHTS A cumulative total of 2,847 cases have been confirmed and 55 deaths have been recorded, with case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.9 percent including 196 imported cases as of 18 October 2020. 1 case is currently isolated in health facilities in the Country; and the National IDU has 99% percent bed occupancy available. 2,655 cases (0 new) have been discharged to date. 135 Health Care Workers have been infected since the beginning of the outbreak, with one death. 9,152cumulative contacts have been registered, of which 8,835 have completed the 14-day quarantine. Currently, 317 contacts are being followed, of these 92.1 percent (n=292) contacts were reached. 722 contacts have converted to cases to date; accounting for 25.3 percent of all confirmed cases. Cumulatively 36,740 laboratory tests have been performed with 7.7 percent positivity rate. There is cumulative total of 1,373 alerts of which 86.5 percent (n=1, 187) have been verified and sampled; Most alerts have come from Central Equatorial State (75.1 percent), Eastern Equatoria State (4.4 percent); Upper Nile State (3.2 percent) and the remaining 17.3 percent are from the other States and Administrative Areas. -

South Sudan: Force Protection Map As of October 2018 White Nile Sennar

South Sudan: Force Protection map as of October 2018 White Nile Sennar The map is shown where the road require force protection for convoy and access denied. Girbanat ! Renk Manyo ! Dakona! SUDAN ! El-galhak Renk ! Kaka Melut ! ! Paloich ! Melut ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wuntau ! ! ! ! ! ! Yida ! ! ! o Adar Bunj ! ! ! ! ! Fashoda o ! Rom ! Pariang ! ! ! ! ! Guel Guk an ! Kodok! Mab ! Malakal ! ! ! ! Akoka ! ! ! ! ! ! Biu Panyikang ! ! ! Agarak ! ! Malual ! Abiemnhom Tonga ! P ! ! o ! Malakal Baliet ! ! ! ! ! Abiemnom ! Wath Wang! Kech ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Banglai ! Aweil North ! Pul Luthni Pakoi ! Baliet Aweil ! ! !! ! Udier Bentiu Keew ! Nyinthok Gok-machar ! East Twic ! P Longochuk ! Mayom o ! Guit ! Chotbora Raga ! Wanyjok Akoc Rubkona Paguir Canal/Pigi ! Chuei ! ! Mayom ny ! Turalei ! Luakpi Warweng Chelkou Yargot ! Guit Kuon ! ! Pakor Wunrok Nhialdu ! Toch ! Aweil West ! ! Mayenjur k igi Mutthiang Fanga Canal/P ! Dome ! Nasir ! ! Ying Juong Aweil Gogrial Gogrial ! ! Nyadin ! Aroyo P ! Dindin Duar Pagil West East ! ! Ulang Maiwut Gossinga ! ! Buaw Nyirol ! Aweil Koch ! ! ! Nasser ! Gabir ! ! Liet-nhom ! Kandag! ! South ! Nyirol ! Haat ! Lankien ! ! Gogrial Ulang ! Raja Elok ! Koch Kosho ! Pagak ! ! Kull Bukteng ! AweilC entre Bar Mayen PKuajok Akop !o!Leer ! ! Ghanna Lunyaker Mayendit ! Walgak Thonyor ! Adok Ayod Pulchuol ! ! Ayod Tanyang ! Rualbet Mayendit! Jwong ! Pathai ! ! Yieth-liet Warrap ! ! ! ! Kaikuiny ! ! Sopo ! Thar-kueng ! Leer Wanding Pabuong ETHIOPIA Tonj ! Romich ! Kier Madol ! ! North ! -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

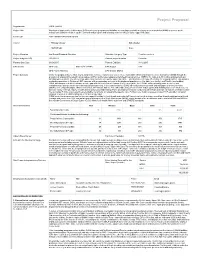

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT in AREAS of RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan

AREA-BASED ASSESSMENT IN AREAS OF RETURN OCTOBER 2019 Renk Town, Renk County, Upper Nile State, South Sudan CONTEXT ASSESSED LOCATION Renk Town is located in Renk County, Upper Nile State, near South Sudan’s border SUDAN Girbanat with Sudan. Since the formation of South Sudan in 2011, Renk Town has been a major Gerger ± MANYO Renk transit point for returnees from Sudan and, since the beginning of the current conflict in Wadakona 1 2013, for internally displaced people (IDPs) fleeing conflict in Upper Nile State. RENK Renk was classified by the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) Analysis Workshop El-Galhak Kurdit Umm Brabit in August 2019 as Phase 4 ‘Emergency’ with 50% of the population in either Phase 3 Nyik Marabat II 2 Kaka ‘Crisis’ (65,997 individuals) or Phase ‘4’ Emergency’ (28,284 individuals). Additionally, MELUT Renk was classified as Phase 5 ‘Extremely Critical’ for Global Acute Malnutrition MABAN (GAM),3 suggesting the prevalence of acute malnutrition was above the World Health Kumchuer Organisation (WHO) recommended emergency threshold with a recent REACH Multi- Suraya Hai Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA) establishing a GAM of above 30%.4 A measles Soma outbreak was declared in June 2019 and access to clean water was reportedly limited, as flagged by the Needs Analysis Working Group (NAWG) and by international NGOs 4 working on the ground. Hai Marabat I Based on the convergence of these factors causing high levels of humanitarian Emtitad Jedit Musefin need and the possibility for larger-scale returns coming to Renk County from Sudan, REACH conducted this Area-Based Assessment (ABA) in order to better understand White Hai Shati the humanitarian conditions in, and population movement dynamics to and from, Renk N e l Town. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION .......................................................