Original Music for the Dance in Australia, 1960-2000. Compiled by Rachel Hocking for This Thesis and Found in Appendix A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PO, Canberra, AX.T. 2601, Australia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 056 303 AC 012 071 TITLE Handbook o Australian h'ult Educatial. INSTITUTION Australian Association of AdultEducati. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 147p. 3rd edition AVAILABLE FROMAustralian Association ofAdult Education, Box 1346, P.O., Canberra, AX.T. 2601,Australia (no price quoted) EDRS PRICE Mr-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DEsCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Day Programs;*Directories; *Educational Facilities; EveningPrograms; *Professional Associations;*University Extension IDENTIFIERS Asia; Australia; New Zealand;South Pacific ABSTRACT The aim of this handbookis to provide a quick reference source for a number ofdifferent publics. It should be of regular assistance to adult andother educators, personnelofficers and social workers, whoseadvice and help is constantlybeing sought about the availability ofadult education facilities intheir own, or in other states. The aim incompiling the Handbook has been tobring together at the National and Statelevels all the major agencies--university, statutory body,government departments and voluntary bodies--that provide programsof teaching for adults open to members of thepublic. There are listed also thelarge number of goverrmental or voluntary bodi_eswhich undertake educationalwork in special areas. The Handbook alsolists all the major public institutions--State Libraries, Museums,and Art Galleriesthat serve importantly to supplement thedirect teaching of adults bytheir collections. New entries includebrief accounts of adult educationin the Northern Territory andin the Territory of Papua-NewGuinea, and the -

Stephen Page on Nyapanyapa

— OUR land people stories, 2017 — WE ARE BANGARRA We are an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation and one of Australia’s leading performing arts companies, widely acclaimed nationally and around the world for our powerful dancing, distinctive theatrical voice and utterly unique soundscapes, music and design. Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national currently in our 28th year. Our dance technique tour of a world premiere work, performed in is forged from over 40,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra, and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. Each an international tour to maintain our global has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait reputation for excellence. Islander background, from various locations across the country. Complementing this touring roster are education programs, workshops and special performances Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres and projects, planting the seeds for the next Strait Islander communities are the heart generation of performers and storytellers. of Bangarra, with our repertoire created on Country and stories gathered from respected Authentic storytelling, outstanding technique community Elders. and deeply moving performances are Bangarra’s unique signature. It’s this inherent connection to our land and people that makes us unique and enjoyed by audiences from remote Australian regional centres to New York. A MESSAGE from Artistic Director Stephen Page & Executive Director Philippe Magid Thank you for joining us for Bangarra’s We’re incredibly proud of our role as cultural international season of OUR land people stories. -

Participating Artists

The Flowers of War – Participating Artists Christopher Latham and in 2017 he was appointed Artist in Ibrahim Karaisli Artistic Director, The Flowers of War Residence at the Australian War Memorial, Muezzin – Re-Sounding Gallipoli project the first musician to be appointed to that Ibrahim Karaisli is head of Amity College’s role. Religion and Values department. Author, arranger, composer, conductor, violinist, Christopher Latham has performed Alexander Knight his whole life: as a solo boy treble in Musicians Baritone – Re-Sounding Gallipoli St Johns Cathedral, Brisbane, then a Now a graduate of the Sydney decade of studies in the US which led to Singers Conservatorium of Music, Alexander was touring as a violinist with the Australian awarded the 2016 German-Australian Chamber Orchestra from 1992 to 1998, Andrew Goodwin Opera Grant in August 2015, and and subsequently as an active chamber Tenor – Sacrifice; Race Against Time CD; subsequently won a year-long contract with musician. He worked as a noted editor with The Healers; Songs of the Great War; the Hessisches Staatstheater in Wiesbaden, Australia’s best composers for Boosey and Diggers’ Requiem Germany. He has performed with many of Hawkes, and worked as Artistic Director Born in Sydney, Andrew Goodwin studied Australia’s premier ensembles, including for the Four Winds Festival (Bermagui voice at the St. Petersburg Conservatory the Sydney Philharmonia Choirs, the Sydney 2004-2008), the Australian Festival of and in the UK. He has appeared with Chamber Choir, the Adelaide Chamber Chamber Music (Townsville 2005-2006), orchestras, opera companies and choral Singers and The Song Company. the Canberra International Music Festival societies in Europe, the UK, Asia and (CIMF 2009-2014) and the Village Building Australia, including the Bolshoi Opera, La Simon Lobelson Company’s Voices in the Forest (Canberra, Scala Milan and Opera Australia. -

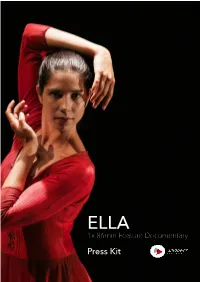

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

Monash's Public Sector Management Institute Gets A$1.5M Boost

• Monash's Public Sector ~~ Management Institute gets a$1.5m boost ~ The Federal Government has granted the university 51.S million over the next two and a half years towards expanding tbe recently-eslablished Public. AMAGAZINE FORTHE UNIVERSITY Sector Management Institute witbin tbe Graduate School of Management. Registered by Australia Post - publication No. VBG0435 The grant, announced by the Minister the Minister for Transport and Com NUMBER 4-88 JUNE 8, 1988 for Employment, Education and Train munications. Senator Gareth Evans. ing, Mr John Dawkins, represents the Professor Chris Selby·Smith will be lion's share of $1.8 million set aside in responsible for health policy and the last budget as the National Public management, and the chairman of the Sector Management Study Fund. Economics department, Professor John Gun lobby's aim: "To According to its director, Professor Head, for tax and expenditure Allan Fels, the primary thrust of the new administration. He will co-operate in the institute will be research, but it wiD also area of tax. law with Professor Yuri involve itself in teaching non-degree Grbich. a former Monash academic, intimidate government courses, providing in-service training for now at the University of New South public sector managers and carrying out Wales Law School. contract research for Australian and The position of Professor of Public foreign governments and private sector Sector Management, concerned with in the frontier society" organisations. effectiveness and efficiency in the public In addition to the successful tender to service, has been advertised. It is ex Australian sbooten are travelling down a well"trodden American road, says noted the Commonwealth, the institute has pected that an appointment will be made lua coatrol lobbyist, Joba Crook, la b1s Master of Arts tbesls. -

Australian Universities' Review Vol. 62, No. 2

vol. 62, no. 2, 2020 Published by NTEU ISSN 0818–8068 AURAustralian Universities’ Review AUR Australian Universities’ Review Editor Editorial Board Dr Ian R. Dobson, Monash University Dr Alison Barnes, NTEU National President Production Professor Timo Aarrevaara, University of Lapland Professor Jamie Doughney, Victoria University Design & layout: Paul Clifton Professor Leo Goedegebuure, University of Melbourne Editorial Assistance: Anastasia Kotaidis AUR is available online as an Professor Jeff Goldsworthy, Monash University e-book and PDF download. Cover photograph: The Sybil Centre, The Women’s Visit aur.org.au for details. College, University of Sydney, NSW. Photograph Dr Mary Leahy, University of Melbourne In accordance with NTEU by Peter Miller. Printed with permission. Professor Kristen Lyons, University of Queensland policy to reduce our impact Contact Professor Dr Simon Marginson, University of Oxford on the natural environment, Matthew McGowan, NTEU General Secretary this magazine is printed Australian Universities’ Review, using vegetable-based inks Dr Alex Millmow, Federation University Australia c/- NTEU National Office, with alcohol-free printing PO Box 1323, South Melbourne VIC 3205 Australia Dr Neil Mudford, University of Queensland initiatives on FSC® certified Phone: +613 9254 1910 Jeannie Rea, Victoria University paper by Printgraphics under ISO 14001 Environmental Email: [email protected] Professor Paul Rodan, Swinburne University of Technology Certification. Website: www.aur.org.au Cathy Rytmeister, Macquarie University Post packaging is 100% Romana-Rea Begicevic, CAPA National President degradable biowrap. Editorial policy Contributions .Style References Australian Universities’ Review Full submission details are available Download the AUR Style Guide at References to be cited according to (AUR, formerly Vestes) is published online at aur.org.au/submissions. -

Elena Kats-Chernin

Elena Kats-Chernin Elena Kats-Chernin photo © Bruria Hammer OPERAS 1 OPERAS 1 OPERAS Die Krönung der Poppea (L'incoronazione di Poppea) Der herzlose Riese Claudio Monteverdi, arranged by Elena Kats-Chernin The Heartless Giant 1643/2012/17 3 hr 2020 55 min Opera musicale in three acts with a prologue 7 vocal soloists-children's choir- 1.1.1.1-1.1.1.1-perc(2)-3.3.3.3.2 4S,M,A,4T,2Bar,B; chorus; 0.2.0.asax.tsax(=barsax).0-0.2.cimbasso.0-perc(2):maracas/cast/claves/shaker/guiro/cr ot/tgl/cyms/BD/SD/tpl.bl/glsp/vib/wdbls/congas/bongos/cowbell-continuo-strings; Tutti stings divided in: vla I–III, vlc I–II, db; Availability: This work is available from Boosey & Hawkes for the world Continuo: 2 gtr players, doubling and dividing the following instruments: banjo, dobro, mandolin, 12-string, electric, classical, Jazz, steal-string, slide, Hawaii, ukulele (some Iphis effects may be produced by the 1997/2005 1 hr 10 min same instrument); 1 vlc(separate from the celli tutti); 1theorbo; 1kbd synthesizer: most used sounds include elec.org, Jazz.org, pipe.org, chamber.org, hpd, clavecin, and ad Opera for six singers and nine musicians lib keyboard instruments as available. 2S,M,2T,Bar 1(=picc).0.1(=bcl).0-1.0.0.0-perc(1):wdbl/cyms/hi hat/xyl/marimba/SD/ World premiere of version: 16 Sep 2012 vib or glsp/3cowbells/crot/BD/tpl.bl/wind chimes/chinese bl/claves- Komische Oper, Berlin, Germany pft(=kbd)-vln.vla.vlc.db Barrie Kosky, director; Orchester und Ensemble der Komischen Oper Berlin Conductor: André de Ridder World Premiere: 03 Dec 1997 Bangarra Dance -

2008, WDA Global Summit

World Dance Alliance Global Summit 13 – 18 July 2008 Brisbane, Australia Australian Guidebook A4:Aust Guide book 3 5/6/08 17:00 Page 1 THE MARIINSKY BALLET AND HARLEQUIN DANCE FLOORS “From the Eighteenth century When we come to choosing a floor St. Petersburg and the Mariinsky for our dancers, we dare not Ballet have become synonymous compromise: we insist on with the highest standards in Harlequin Studio. Harlequin - classical ballet. Generations of our a dependable company which famous dancers have revealed the shares the high standards of the glory of Russian choreographic art Mariinsky.” to a delighted world. And this proud tradition continues into the Twenty-First century. Call us now for information & sample Harlequin Australasia Pty Ltd P.O.Box 1028, 36A Langston Place, Epping, NSW 1710, Australia Tel: +61 (02) 9869 4566 Fax: +61 (02) 9869 4547 Email: [email protected] THE WORLD DANCES ON HARLEQUIN FLOORS® SYDNEY LONDON LUXEMBOURG LOS ANGELES PHILADELPHIA FORT WORTH Ausdance Queensland and the World Dance Alliance Asia-Pacific in partnership with QUT Creative Industries, QPAC and Ausdance National and in association with the Brisbane Festival 2008 present World Dance Alliance Global Summit Dance Dialogues: Conversations across cultures, artforms and practices Brisbane 13 – 18 July 2008 A Message from the Minister On behalf of our Government I extend a warm Queensland welcome to all our local, national and international participants and guests gathered in Brisbane for the 2008 World Dance Alliance Global Summit. This is a seminal event on Queensland’s cultural calendar. Our Government acknowledges the value that dance, the most physical of the creative forms, plays in communicating humanity’s concerns. -

A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes: Essays in Honour of Stephen A. Wild

ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD Stephen A. Wild Source: Kim Woo, 2015 ESSAYS IN HONOUR OF STEPHEN A. WILD EDITED BY KIRSTY GILLESPIE, SALLY TRELOYN AND DON NILES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A distinctive voice in the antipodes : essays in honour of Stephen A. Wild / editors: Kirsty Gillespie ; Sally Treloyn ; Don Niles. ISBN: 9781760461119 (paperback) 9781760461126 (ebook) Subjects: Wild, Stephen. Essays. Festschriften. Music--Oceania. Dance--Oceania. Aboriginal Australian--Songs and music. Other Creators/Contributors: Gillespie, Kirsty, editor. Treloyn, Sally, editor. Niles, Don, editor. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Stephen making a presentation to Anbarra people at a rom ceremony in Canberra, 1995’ (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies). This edition © 2017 ANU Press A publication of the International Council for Traditional Music Study Group on Music and Dance of Oceania. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this book contains images and names of deceased persons. Care should be taken while reading and viewing. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Foreword . xi Svanibor Pettan Preface . xv Brian Diettrich Stephen A . Wild: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes . 1 Kirsty Gillespie, Sally Treloyn, Kim Woo and Don Niles Festschrift Background and Contents . -

Mckee, Alan (1996) Making Race Mean : the Limits of Interpretation in the Case of Australian Aboriginality in Films and Television Programs

McKee, Alan (1996) Making race mean : the limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4783/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Making Race Mean The limits of interpretation in the case of Australian Aboriginality in films and television programs by Alan McKee (M.A.Hons.) Dissertation presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Glasgow in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Glasgow March 1996 Page 2 Abstract Academic work on Aboriginality in popular media has, understandably, been largely written in defensive registers. Aware of horrendous histories of Aboriginal murder, dispossession and pitying understanding at the hands of settlers, writers are worried about the effects of raced representation; and are always concerned to identify those texts which might be labelled racist. In order to make such a search meaningful, though, it is necessary to take as axiomatic certain propositions about the functioning of films: that they 'mean' in particular and stable ways, for example; and that sophisticated reading strategies can fully account for the possible ways a film interacts with audiences. -

Beethoven's Eroica

BEETHOVEN’S EROICA 10–12 MAY 2018 CONCERT PROGRAM Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis conductor Moye Chen piano Vine Concerto for Orchestra – Composer in Residence Liszt Piano Concerto No.1 INTERVAL Beethoven Symphony No.3 Eroica Running time: 2 hours, including a 20-minute interval In consideration of your fellow patrons, the MSO thanks you for silencing and dimming the light on your phone. The MSO acknowledge the Traditional Owners of the land on which we are performing. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and the Elders from mso.com.au other communities who may be in attendance. (03) 9929 9600 2 MELBOURNE SYMPHONY SIR ANDREW DAVIS ORCHESTRA CONDUCTOR Established in 1906, the Melbourne Chief Conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra (MSO) is an Symphony Orchestra, Sir Andrew arts leader and Australia’s longest- Davis is also Music Director and running professional orchestra. Chief Principal Conductor of the Lyric Opera Conductor Sir Andrew Davis has of Chicago. He is Conductor Laureate been at the helm of MSO since 2013. of both the BBC Symphony Orchestra Engaging more than 4 million people and the Toronto Symphony, where he each year, the MSO reaches a variety has also been named interim Artistic of audiences through live performances, Director until 2020. recordings, TV and radio broadcasts In a career spanning more than 40 and live streaming. years he has conducted virtually all The MSO also works with Associate the world’s major orchestras and opera Conductor Benjamin Northey and companies, and at the major festivals. Cybec Assistant Conductor Tianyi Lu, Recent highlights have included as well as with such eminent recent Die Walküre in a new production guest conductors as Tan Dun, John at Chicago Lyric. -

14Th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2012

australian societa y fo r s music educationm e What Would Peggy Do? i ncorporated 14th Annual Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address 2012 Michael Kieran Harvey The New Music Network established the Peggy Glanville-Hicks Address in 1999 in honour of one of Australia’s great international composers. It is an annual forum for ideas relating to the creation and performance of Australian music. In the spirit of the great Australian composer Peggy Glanville-Hicks, an outstanding advocate of Australian music delivers the address each year, challenging the status quo and raising issues of importance in new music. In 2012, Michael Kieran Harvey was guest speaker presenting his Address entitled What Would Peggy Do? at the Sydney Conservatorium on 22 October and BMW Edge Fed Square in Melbourne on 2 November 2012. The transcripts are reproduced with permission by Michael Kieran Harvey and the New Music Network. http://www.newmusicnetwork.com.au/index.html Australian Journal of Music Education 2012:2,59-70 Just in case some of you are wondering about I did read an absolutely awe-inspiring Peggy what to expect from the original blurb for this Glanville-Hicks Address by Jon Rose however, address: the pie-graphs didn’t quite work out, and and I guess my views are known to the address powerpoint is so boring, don’t you agree? organisers, so, therefore, I will proceed, certain For reasons of a rare dysfunctional condition in the knowledge that I will offend many and I have called (quote) “industry allergy”, and for encourage, I hope, a valuable few.