Bangarra Dance Theatre: Rethinking Indigeneity in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE EDUCATION NOTES ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated December 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that these Education Notes contain names and images of, and quotes from, deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Elma Kris, Rika Hamaguchi and Tyrel Dulvarie, photos by Daniel Boud & Jacob Nash, image created by Jacob Nash Back Cover: Elma Kris, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION Bangarra is rooted in two worlds, and through dance we connect to both, embodying ancient practices and igniting contemporary songlines. Our productions are our contemporary acts of ceremony, our way of protecting and preserving our unique songline. Knowledge Ground: 30 years of sixty five thousand is a curated collection of the arfefacts of these ceremonies – iconic set pieces, soundscapes, and costumes, which reveal the influences and themes that underpin our practice. -

Stephen Page on Nyapanyapa

— OUR land people stories, 2017 — WE ARE BANGARRA We are an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisation and one of Australia’s leading performing arts companies, widely acclaimed nationally and around the world for our powerful dancing, distinctive theatrical voice and utterly unique soundscapes, music and design. Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national currently in our 28th year. Our dance technique tour of a world premiere work, performed in is forged from over 40,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra, and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. Each an international tour to maintain our global has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait reputation for excellence. Islander background, from various locations across the country. Complementing this touring roster are education programs, workshops and special performances Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres and projects, planting the seeds for the next Strait Islander communities are the heart generation of performers and storytellers. of Bangarra, with our repertoire created on Country and stories gathered from respected Authentic storytelling, outstanding technique community Elders. and deeply moving performances are Bangarra’s unique signature. It’s this inherent connection to our land and people that makes us unique and enjoyed by audiences from remote Australian regional centres to New York. A MESSAGE from Artistic Director Stephen Page & Executive Director Philippe Magid Thank you for joining us for Bangarra’s We’re incredibly proud of our role as cultural international season of OUR land people stories. -

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

Dubboo Life of a Songman Program Credits

Dubboo: Life of A Songman Program Credits Directed by WAYNE BLAIR & NEL MINCHIN Produced by IVAN O’MAHONEY Cultural Producers BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE Edited by NICK MEYERS ASE Music by DAVID PAGE “DUBBOO – LIFE OF A SONGMAN” Co-presented by Carriageworks & Bangarra Dance Theatre Artistic Director STEPHEN PAGE Creative Ensemble ARCHIE ROACH DJAKAPURRA MUNYARRYUN URSULA YOVICH BEN GRAETZ HUNTER PAGE-LOCHARD BRENDON BONEY BANGARRA DANCERS STEPHEN PAGE JENNIFER IRWIN JACOB NASH ALANA VALENTINE MATT COX Music Production & Arrangement STEVE FRANCIS String Arrangements IAIN GRANDAGE 1 String Quartet VERONIQUE SERRET STEPHANIE ZARKA CARL ST. JACQUES PAUL GHICA Stage Director PETER SUTHERLAND Director, Technical & Production JOHN COLVIN Rehearsal Director DANIEL ROBERTS Production Manager CAT STUDLEY Company Manager CLOUDIA ELDER Stage Manager LILLIAN HANNAH U Head Electrician CHRIS DONNELLY Head of Wardrobe MONICA SMITH Sound & AV Technician EMJAY MATTHEWS Production Trainee STEPH STORR Bangarra extends their thanks to the many people who helped bring together this celebration. A special thank you to the Page family for entrusting the company with this important work to honour their brother, son and uncle. Featured Bangarra productions Brolga (2001), Fish (1997), Spear (2015 feature film), Skin (2000), Ninni (1994), Bush, Praying Mantis Dreaming (1992), Ochres (1995) Key Credits STEPHEN PAGE FRANCES RINGS DJAKAPURRA MUNYARRYUN DAVID PAGE 2 STEVE FRANCIS JOHN MATKOVIC PETER ENGLAND JENNIFER IRWIN JOSEPH MERCURIO EMILY AMISANO MARK HOWETT ARCHIE -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2012-2013

_2012/13 Sydney Opera House Annual Report Celebrating 40 years in 2013 2012/13 Contents 3 Letter to Minister 3 Our History 3 Who We Are 4 Our Mission 5 Elements of Our Strategy 5 Our Values 6 Highlights 7 Awards 8 Chairman’ s Message 10 CEO ’s Message 12 Element 1: Our Stakeholders 14 Element 2: The Building 16 Element 3: Performing Arts 16 Presenting Companies 20 The Opera House Presents 24 Element 4: Visitor Experience 26 Element 5: Our Business Agility 27 Organisation Chart 28 Corporate Governance 30 Trust Members 34 People and Culture 38 Financial Overview 41 Financial Statements 74 Government Reporting 97 Donor Acknowledgement 101 Contact Information 102 Index Cover Image 103 Corporate Partners Sydney Opera House opened in 1973 and celebrates its 40th Anniversary in the 2013 year. 3 Our History Who We Are _1957 _2004 Sydney Opera House is a global icon, the most internationally recognised symbol of Australia and one of the great buildings Jørn Utzon wins Sydney Utzon Room opened – of the world. Opera House design first venue at Sydney competition. Opera House designed We are committed to continuing the legacy of Utzon’s creative by Jørn Utzon. genius by creating, producing and presenting the most acclaimed, imaginative and engaging performing arts experiences from Australia _1959 Recording Studio and around the world: onsite, offsite and online. Work begins on opened. Stage 1 – building the We are one of the world’s busiest performing arts centres, with seven primary performance venues in use nearly every day of the foundations. _2005 year. In 2012/13, 1,895 live performances were enjoyed by more than National Heritage 1.37 million people. -

Belvoir Annual Report 2010

Belvoir Annual Report 2010 Belvoir Annual Report 2010 25 Belvoir St, Surry Hills NSW 2010 admin +61 (0)2 9698 3344 fax +61 (0)2 9319 3165 box office +61 (0)2 9699 3444 [email protected] belvoir.com.au Toby Schmitz & Robin McLeavy in Measure for Measure. Photo: Heidrun Löhr. Contents The Belvoir Story 02 Core Values, Principles and Mission 03 Chair’s Report 04 Artistic Director’s Report 06 General Manager’s Report 08 New Artistic Director’s Note 11 2010 Season and Tours 12 B Sharp 26 Creative and Artistic Development 28 Awards 29 Education 30 Board and Staff 33 Donors 34 Partners and Government Supporters 36 Financial Statements 37 Key Performance Indicators 38 Directors’ Report 40 Statement of Comprehensive Income 44 Statement of Financial Position 45 Statements of Cash Flows and Changes in Equity 46 Notes to the Financial Statements 47 Auditor’s Independence Declaration and Report 56 01 The Belvoir Story Core Values and Principles One building. • Belief in the primacy of the Six hundred people. artistic process Thousands of stories. • Clarity and playfulness in One dream. storytelling • A sense of community within the theatrical environment When the Nimrod Theatre building in Belvoir Belvoir’s position as one of Australia’s most • Responsiveness to current Street, Surry Hills, was threatened with innovative and acclaimed theatre companies demolition in 1984, more than 600 people has been determined by such landmark social and political issues – ardent theatre lovers together with arts, productions as The Diary of a Madman, The • Equality, ethical standards and entertainment and media professionals – Blind Giant is Dancing, Cloudstreet, Measure shared ownership of artistic formed a syndicate to buy the building and for Measure, Keating!, Parramatta Girls, Exit and company achievements save this unique performance space in the King, The Alchemist, Hamlet, Waiting inner-city Sydney. -

Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2012/13

_2012/13 Sydney Opera House Annual Report Celebrating 40 years in 2013 2012/13 Contents 3 Letter to Minister 3 Our History 3 Who We Are 4 Our Mission 5 Elements of Our Strategy 5 Our Values 6 Highlights 7 Awards 8 Chairman’s Message 10 CEO’s Message 12 Element 1: Our Stakeholders 14 Element 2: The Building 16 Element 3: Performing Arts 16 Presenting Companies 20 The Opera House Presents 24 Element 4: Visitor Experience 26 Element 5: Our Business Agility 27 Organisation Chart 28 Corporate Governance 30 Trust Members 34 People and Culture 38 Financial Overview 41 Financial Statements 74 Government Reporting 97 Donor Acknowledgement 101 Contact Information 102 Index Cover Image 103 Corporate Partners Sydney Opera House opened in 1973 and celebrates its 40th Anniversary in the 2013 year. 3 Our History Who We Are _1957 _2004 Sydney Opera House is a global icon, the most internationally recognised symbol of Australia and one of the great buildings Jørn Utzon wins Sydney Utzon Room opened – of the world. Opera House design first venue at Sydney competition. Opera House designed We are committed to continuing the legacy of Utzon’s creative by Jørn Utzon. genius by creating, producing and presenting the most acclaimed, imaginative and engaging performing arts experiences from Australia _1959 Recording Studio and around the world: onsite, offsite and online. Work begins on opened. Stage 1 – building the We are one of the world’s busiest performing arts centres, with foundations. _2005 seven primary performance venues in use nearly every day of the year. In 2012/13, 1,895 live performances were enjoyed by more than National Heritage 1.37 million people. -

A Study Guide by Katy Marriner

A FOOT IN EACH WORLD. A HEART IN NONE © ATOM 2016 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-936-8 http://theeducationshop.com.au Spear (2015), a feature film directed by Stephen Page, tells an Indigenous Australian story through movement, dance, sound, visual design and digital Australian Curriculum Learning media. A young Aboriginal man Djali journeys through his community Areas: Year 10 attempting to understand what it means to be a man. Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers English are advised that Spear contains voices and names of http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/english/ deceased people. curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level10 Curriculum links Humanities and Social Sciences: History http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ Spear is suitable for secondary students in Years humanities-and-social-sciences/history/curriculum/f- 10 – 12 in the learning areas of Dance, Drama, 10?layout=1#level10 English, History and Media. The Arts: Dance Spear can be used as a resource to address the http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/the-arts/ Australian Curriculum: Cross-curriculum priority – dance/curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level9-10 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures. The film’s depiction of the experiences of Indigenous Australians, particularly of adult males, The Arts: Drama provides opportunities for students to engage in http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/the-arts/ discussions about Indigenous Australian identity drama/curriculum/f-10?layout=1#level9-10 and belonging and to examine the influences of tra- ditional Indigenous views and values, as well as the The Arts: Media Arts impact of the views and values of contemporary Australian society. -

Dark-Emu Studyguide.Pdf

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated September 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this Study Guide contains names and images of, and quotes from, deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Bangarra ensemble, photo by Daniel Boud Back Cover: Yolanda Lowatta, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS Inspired by Bruce Pascoe’s award-winning book of the same name, Dark Emu explores the vital life force 03 of flora and fauna in a series of dance stories. Directed Introduction by Stephen Page, Dark Emu is a dramatic and evocative dance response to the assault on land, people and spirit. We celebrate this sharing of knowledge, the heritage 04 of careful custodianship, and the beauty that Bruce Using this Study Guide Pascoe’s vision urges us to leave to the children. -

30Years Studyguide.Pdf

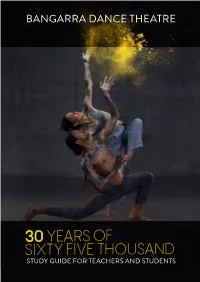

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated September 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this Study Guide contains images, names, and writings of deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Rika Hamaguchi and Tyrel Dulvarie, photo by Daniel Boud Back Cover: Rika Hamaguchi, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION CONTENTS The purpose of this Study Guide is to provide information and contextual background about the works presented 03 in Bangarra Dance Theatre’s 30th anniversary season, Introduction/Contents Bangarra: 30 years of sixty five thousand. Reading the Guide, discussing the themes, and responding to the questions proposed, will assist teachers and students in thinking critically about the works, and form 04 Using this Study Guide personal responses. We encourage students and teachers to engage emotionally and imaginatively with the performance 05 Contemporary Indigenous Dance Theatre and to be curious about how these works were inspired and how they impact audiences. -

Reconciliation News October 2019

News ReconciliationStories about Australia’s journey to equality and unity Luke Pearson talks IndigenousX Bangarra Dance Theatre turns 30! Preserving the songs of Arrernte women TREATIES: THE MOMENTUM IS BUILDING 42 October 2019 Reconciliation News is a national magazine produced by Reconciliation Australia twice a year. Its aim is to inform and inspire readers with stories relevant to the process of reconciliation between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians. CONTACT US JOIN THE CONVERSATION reconciliation.org.au facebook.com/ReconciliationAus [email protected] twitter.com/RecAustralia 02 6273 9200 @reconciliationaus Reconciliation Australia acknowledges the Traditional Reconciliation Australia is an independent, not-for- Owners of Country throughout Australia and profit organisation promoting reconciliation by building recognises their continuing connection to lands, relationships, respect and trust between the wider waters and communities. We pay our respects to Australian community and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures; and to Islander peoples. Visit reconciliation.org.au Elders both past and present. to find out more. Cover: Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Tyrel Dulvarie. Image by Daniel Boud. Issue no. 42 / October 2019 3 CONTENTS FEATURES 8 Bangarra turns 30! To mark its 30-year anniversary, Bangarra Dance Theatre has just completed a triumphant four-month national tour. 10 Treaties: the momentum is building As the Uluru Statement from the Heart records, treaty-making is a key aspiration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 12 The Arrernte Women’s Project: Songs to Live By 10 Rachel Perkins pens a moving essay on her journey to record the sacred songs of Arrernte women in Central Australia.