Dark-Emu Studyguide.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Cultures 11/11

.. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board, Australia Council PO Box 788 Strawberry Hills NSW 2012 Tel: (02) 9215 9065 Toll Free: 1800 226 912 Fax: (02) 9215 9061 Email: [email protected] www.ozco.gov.au cultures . WRITING ..... Protocols for Producing Indigenous Australian Literature An initiative of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait ISBN: 0 642 47240 8 Islander Arts Board of the Australia Council Writing Cultures: Protocols for Producing Indigenous Australian Literature Recognition and protection 18 contents Resources 18 Introduction 1 Copyright 20 Using the Writing Cultures guide 2 What is copyright? 20 What are protocols? 3 How does copyright protect literature? 20 What is Indigenous literature? 3 Who owns copyright? 20 Special nature of Indigenous literature 4 What rights do copyright owners have? 21 Collaborative works 21 Indigenous heritage 5 Communal ownership vs. joint ownership 21 Current protection of heritage 6 How long does copyright last? 22 Principles and protocols 8 What is the public domain? 22 Respect 8 What are moral rights? 22 Acknowledgement of country 8 Licensing for publication 22 Representation 8 Assigning copyright 23 Accepting diversity 8 Publishing contracts 23 Living cultures 9 Managing copyright to protect your interests 23 Indigenous control 9 Copyright notice 23 Commissioning Indigenous writers 9 Moral rights notice 24 Communication, consultation and consent 10 When is copyright infringed? 24 Creation stories 11 Fair dealings provisions 24 © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Recording oral stories 11 -

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories

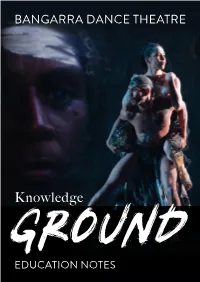

BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE EDUCATION NOTES ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY Bangarra Dance Theatre pays respect and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we meet, create, and perform. We also wish to acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples whose customs and cultures inspire our work. INDIGENOUS CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (ICIP) Bangarra acknowledges the industry standards and protocols set by the Australia Council for the Arts Protocols for Working with Indigenous Artists (2007). Those protocols have been widely adopted in the Australian arts to respect ICIP and to develop practices and processes for working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and cultural heritage. Bangarra incorporates ICIP into the very heart of our projects, from storytelling, to dance, to set design, language and music. © Bangarra Dance Theatre 2019 Last updated December 2019 WARNING Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that these Education Notes contain names and images of, and quotes from, deceased persons. Photo Credits Front Cover: Elma Kris, Rika Hamaguchi and Tyrel Dulvarie, photos by Daniel Boud & Jacob Nash, image created by Jacob Nash Back Cover: Elma Kris, photo by Daniel Boud 2 INTRODUCTION Bangarra is rooted in two worlds, and through dance we connect to both, embodying ancient practices and igniting contemporary songlines. Our productions are our contemporary acts of ceremony, our way of protecting and preserving our unique songline. Knowledge Ground: 30 years of sixty five thousand is a curated collection of the arfefacts of these ceremonies – iconic set pieces, soundscapes, and costumes, which reveal the influences and themes that underpin our practice. -

Australia Council Nationhood, National Identity and Democracy

AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FOR THE ARTS SUBMISSION NATIONHOOD, NATIONAL IDENTITY AND DEMOCRACY INQUIRY October 2019 1 CONTENTS Contents 2 About the Australia Council 3 Executive summary 4 Submission 6 Our arts shape and communicate our cultural identity 6 First Nations arts are central to understanding who we are as Australians 7 Our diverse artistic expression is reshaping our contemporary national identity 9 Our creative expressions are an antidote to declining public trust and social divisions 13 Conclusion 14 Policy options 15 2 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL The Australia Council is the Australian Government’s principal arts funding and advisory body. We champion and invest in Australian arts and creativity. We support all facets of the creative process and are committed to ensuring all Australians can experience the benefits of the arts and feel part of the cultural life of this nation. The Australia Council’s investment in arts and creativity presents a vital opportunity to develop Australia’s identity and reputation as a sophisticated and creative nation with a confident, connected community. Australia’s arts and creativity are among our nation’s most powerful assets, delivering substantial public value across portfolios: investing in the arts is investing in the social, economic and cultural success of our nation. For half a century the Australia Council has invested in activity that directly and powerfully contributes to Australia’s cultural identity and social cohesion. Our vision Creativity Connects Us1 is underpinned by five strategic objectives: • More Australians are transformed by arts experiences • Our arts reflect us • First Nations arts and culture are cherished • Arts and creativity are thriving • Arts and creativity are valued. -

Bangarra Dance Theatre: Rethinking Indigeneity in Australia

Bangarra Dance Theatre: Rethinking Indigeneity in Australia A thesis by: Charlotte Schuitenmaker 10212795 rMA Art Studies Supervisor: Dr. B. Titus Second reader: Prof. Dr. J.J.E. Kursell University of Amsterdam 21/01/2019 CONTENT INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….. 3 1 – BANGARRA’S EXPRESSIONS…...…………………………………………9 1.1 – Dance and Indigenous Australia………………………………………9 1.1.1 – Dance and music as modes of expression…………………...11 1.1.2 – Dance and music as systems of authority…………………...14 1.2 – Contemporary dancing………………………………………………..15 1.2.1 – Contemporary dance: An Overview......................................15 1.2.2 – Bangarra’s dance…………………………………………….20 1.3 – Presenting Indigeneity………………………………………………...22 1.3.1 – Bangarra’s performances…………………………………….22 1.3.2 – Bangarra’s promotion………………………………………. 31 2 – REASSEMBLING BANGARRA: THE INSTITUTION AS AND WITHIN A NETWORK……………………. 34 2.1 – Bangarra’s establishment……………………………………………...37 2.2 – A Page family business: choreographer, dancer and songman………. 39 2.3 – The theatre…………………………………………………………… 45 2.4 – Audiences and tickets………………………………………………....49 2.5 – Institutions and modernity...................................................................51 3 – MESSAGES: THE POLITICS OF IDENTITY AND STORIES…………54 3.1 – Indigeneity as identity…………………………………………………55 3.2 – Contemporary storytelling…………………………………………….60 3.2.1 – Stories: past-present-future…………………………….…....64 CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………….……67 REFERENCES……………………………………………………….……….……71 2 INTRODUCTION The Bangarra Dance Theatre Company is a Sydney-based institution that produces contemporary dance theatre shows inspired by Indigenous cultures in Australia. Carole Johnson, a dancer of African-American heritage, established the company in 1989, with Stephen George Page as Artistic Director since 1991. Page’s Aboriginal heritage stems from both the Nunukul people and the Munaldjali, a clan of the Yugambeh tribe in the south east of Queensland. Since 1992 the company has produced new shows almost annually and the team tours across the country. -

Teachers' Notes the Little Red, Yellow, Black Book

Educational Resources: Teachers’ notes The Little Red Yellow Black website, http://lryb.aiatsis.gov.au Teachers’ Notes The Little Red, Yellow, Black Book: An introduction to Indigenous Australia An important note to teachers The following points are important considerations to remember when teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander studies. These cautions should be consulted throughout the course and shared with students. Aboriginal studies and Torres Strait Islander studies are not only about historical events and contemporary happenings. More importantly, they are about people and their lives. Consequently, consideration of, and sensitivity towards, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are essential, as is collaboration with relevant communities. • Where possible, consult Indigenous people and Indigenous sources for information, many links to which are contained in these notes. Try to work with your local Indigenous community people and elders and respect the intellectual and cultural property rights of Indigenous people. • Consult reliable sources. Be discerning and look for credible information. Indigenous Australians are careful to speak only about the country or culture they’re entitled to speak about. Generally Indigenous people won’t tell others about sacred images or stories, however, over time, and with the effects of colonisation, some things that are sacred, or secret, to Indigenous groups have been disseminated. Be sensitive to requests not to talk about or include some material. Ensure that what you’re reading derives from a community or elders’ knowledge, or from reputable research. Remember too that less-than-polished publications can still be valuable. • Use only the information and images you know have been cleared for reproduction or use in the public domain. -

Dubboo Life of a Songman Program Credits

Dubboo: Life of A Songman Program Credits Directed by WAYNE BLAIR & NEL MINCHIN Produced by IVAN O’MAHONEY Cultural Producers BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE Edited by NICK MEYERS ASE Music by DAVID PAGE “DUBBOO – LIFE OF A SONGMAN” Co-presented by Carriageworks & Bangarra Dance Theatre Artistic Director STEPHEN PAGE Creative Ensemble ARCHIE ROACH DJAKAPURRA MUNYARRYUN URSULA YOVICH BEN GRAETZ HUNTER PAGE-LOCHARD BRENDON BONEY BANGARRA DANCERS STEPHEN PAGE JENNIFER IRWIN JACOB NASH ALANA VALENTINE MATT COX Music Production & Arrangement STEVE FRANCIS String Arrangements IAIN GRANDAGE 1 String Quartet VERONIQUE SERRET STEPHANIE ZARKA CARL ST. JACQUES PAUL GHICA Stage Director PETER SUTHERLAND Director, Technical & Production JOHN COLVIN Rehearsal Director DANIEL ROBERTS Production Manager CAT STUDLEY Company Manager CLOUDIA ELDER Stage Manager LILLIAN HANNAH U Head Electrician CHRIS DONNELLY Head of Wardrobe MONICA SMITH Sound & AV Technician EMJAY MATTHEWS Production Trainee STEPH STORR Bangarra extends their thanks to the many people who helped bring together this celebration. A special thank you to the Page family for entrusting the company with this important work to honour their brother, son and uncle. Featured Bangarra productions Brolga (2001), Fish (1997), Spear (2015 feature film), Skin (2000), Ninni (1994), Bush, Praying Mantis Dreaming (1992), Ochres (1995) Key Credits STEPHEN PAGE FRANCES RINGS DJAKAPURRA MUNYARRYUN DAVID PAGE 2 STEVE FRANCIS JOHN MATKOVIC PETER ENGLAND JENNIFER IRWIN JOSEPH MERCURIO EMILY AMISANO MARK HOWETT ARCHIE -

Darkemu-Program.Pdf

1 Bringing the connection to the arts “Broadcast Australia is proud to partner with one of Australia’s most recognised and iconic performing arts companies, Bangarra Dance Theatre. We are committed to supporting the Bangarra community on their journey to create inspiring experiences that change society and bring cultures together. The strength of our partnership is defined by our shared passion of Photo: Daniel Boud Photo: SYDNEY | Sydney Opera House, 14 June – 14 July connecting people across Australia’s CANBERRA | Canberra Theatre Centre, 26 – 28 July vast landscape in metropolitan, PERTH | State Theatre Centre of WA, 2 – 5 August regional and remote communities.” BRISBANE | QPAC, 24 August – 1 September PETER LAMBOURNE MELBOURNE | Arts Centre Melbourne, 6 – 15 September CEO, BROADCAST AUSTRALIA broadcastaustralia.com.au Led by Artistic Director Stephen Page, we are Bangarra’s annual program includes a national in our 29th year, but our dance technique is tour of a world premiere work, performed in forged from more than 65,000 years of culture, Australia’s most iconic venues; a regional tour embodied with contemporary movement. The allowing audiences outside of capital cities company’s dancers are dynamic artists who the opportunity to experience Bangarra; and represent the pinnacle of Australian dance. an international tour to maintain our global WE ARE BANGARRA Each has a proud Aboriginal and/or Torres reputation for excellence. Strait Islander background, from various BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE IS AN ABORIGINAL Complementing Bangarra’s touring roster are locations across the country. AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER ORGANISATION AND ONE OF education programs, workshops and special AUSTRALIA’S LEADING PERFORMING ARTS COMPANIES, WIDELY Our relationships with Aboriginal and Torres performances and projects, planting the seeds for ACCLAIMED NATIONALLY AND AROUND THE WORLD FOR OUR Strait Islander communities are the heart of the next generation of performers and storytellers. -

Dark Emu ‘Hoax’: Takedown Reveals the Emperor Has No Clothes

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Dark Emu ‘hoax’: takedown reveals the emperor has no clothes Author Bruce Pascoe. • Victoria Grieve-Williams • July 2, 2021 There is much terrible irony in Dark Emu’s struggle to shoehorn classical Aboriginal Australia into the supposedly advanced world of agriculture.” - Peter Sutton Can the Dark Emu scandal be explained by the fact that Australians seem inordinately susceptible to a good old-fashioned literary hoax? From the infamous Ern Malley affair through to Norma Khouri and Helen Demidenko, we seem to have an appetite for being misled. There are examples in the Aboriginal world, too. Ian Carmen, a white taxidriver from Adelaide, posed as a Pitjantjatjara survivor of the Stolen Generation, Wanda Koolmatrie, to write an “autobiography” called My Own Sweet Time. This book was used as a text for the NSW Higher Schools certificate curriculum. In 2014, Bruce Pascoe, exhibiting zeal and showmanship, produced a book that has now sold more than 260,000 copies. Surprise, it says that we Indigenous Australians are more like white people, and therefore, somehow, more sophisticated than “mere” hunter-gatherers. Well thanks, but no thanks. Pascoe’s thesis went entirely against my lived experience, learning as a child to the “summer” and “winter” camps of my mother’s people. They moved to the Barrington 2 Mountains, even in snow, for fatter game and thicker furs, and returned to the coast for the mullet runs in spring, feasting and meeting with other groups. The bunya bunya from the giant cones in the bunya tree, and the huge mulloway my grandfather caught, kept the family alive during the Depression. -

He Wants to Save the Present with the Indigenous Past

_ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ He Wants to Save the Present With the Indigenous Past Bruce Pascoe’s book “Dark Emu” sparked a reconsideration of Australian history. Now he hopes to use his writing to revive Aboriginal community. Bruce Pascoe in a field of mandadyan nalluk, also known as “dancing grass.”Credit...AnnaMaria Antoinette D'Addario for The New York Times By Damien Cave Aug. 20, 2020 WALLAGARAUGH, Australia — Bruce Pascoe stood near the ancient crops he has written about for years and discussed the day’s plans with a handful of workers. Someone needed to check on the yam daisy seedlings. A few others would fix up a barn or visitor housing. Most of them were Yuin men, from the Indigenous group that called the area home for thousands of years, and Pascoe, who describes himself as “solidly Cornish” and “solidly Aboriginal,” said inclusion was the point. The farm he owns on a remote hillside a day’s drive from Sydney and Melbourne aims to correct for colonization — to ensure that a boom in native foods, caused in part by his book, “Dark Emu,” does not become yet another example of dispossession. “I became concerned that while the ideas were being accepted, the inclusion of Aboriginal people in the industry was not,” he said. “Because that’s what Australia has found hard, including Aboriginal people in anything.” The lessons Pascoe, 72, seeks to impart by bringing his own essays to life — and to dinner tables — go beyond appropriation. He has argued that the Indigenous past 2 should be a guidebook for the future, and the popularity of his work in recent years points to a hunger for the alternative he describes: a civilization where the land and sea are kept healthy through cooperation, where resources are shared with neighbors, where kindness even extends to those who seek to conquer. -

Draft Transcript UTS Zoom Event with Verity Firth and Bruce Pascoe

2012 National Disability Award winner Draft Transcript Draft Transcript UTS Zoom event with Verity Firth and Bruce Pascoe Friday, 29 May 2020 About This Document This document contains a draft transcript only. This draft transcript has been taken directly from the text of live captioning provided by The Captioning Studio and any errors spotted by the captioner have been corrected; however, it may still contain errors. The transcript may also contain ‘inaudibles’ if there were occasions when audio quality was compromised during the event. The Captioning Studio accepts no liability for any event or action resulting from this draft transcript. The draft transcript must not be published without The Captioning Studio’s written permission. DRAFT Transcript produced by The Captioning Studio W: captioningstudio.com T: (08) 8463 1639 Page 1 2012 National Disability Award winner Draft Transcript VERITY FIRTH: Hello, everyone. I'm just going to wait for our webinar to fill up a bit. I can see the participants rising. We've had a wonderful response to this conversation today with Bruce Pascoe, so I'm just watching you all come in from the waiting room and we'll start in a minute or two. This is fantastic. We're reaching almost 500 people now logged on. I will wait for another minute and then we'll start our conversation so we can kick off on time. Alright, I'm just sorting out my own picture here so I can see Bruce. Thank you, everybody. Thank you very much for joining us today for this special Reconciliation Week event. -

Bruce Pascoe and the First Dancing Grass Harvest In

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 'Time to embrace history of country': Bruce Pascoe and the first dancing grass harvest in 200 years Writer’s farm in East Gippsland, Victoria, is producing native grains for flour and bread using traditional Aboriginal techniques by Lorena Allam and Isabella Moore Wed 13 May 2020 On the hill above Bruce Pascoe’s farm near Mallacoota in Victoria’s East Gippsland, there’s a sea of mandadyan nalluk. Translated from Yuin, the language of the country, it means “dancing grass”. Pascoe and his small team of coworkers have never done a harvest like this before. There’s so much grass that both sheds are full, and Pascoe says they are “racing against the clock to refine our methods so we can extract the seed and make the flour. We have got to get this done in two or three weeks before the seed completely drops.” The team had a ceremony for the the beginning of the harvest because they think it’s the first time in 200 years that mandadyan nalluk has been harvested for food. “And some of these people are descended from those who would have done the last harvest,” Pascoe says. “That’s what this farm is all about – trying to make sure that Aboriginal people are part of the resurgence in these grains, rather than being on the periphery and being dispossessed again.” They had intended to harvest a different, more promising crop of kangaroo grass but it was destroyed by the summer’s catastrophic bushfires. As a CFA volunteer, Pascoe spent weeks on the fire and recovery efforts. -

Bruce Pascoe's Earth, an Indigenous Ecological Allegory

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online AJE: Australasian Journal of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology, Vol. 4, 2014/2015 ASLEC-ANZ Learning to Read Country: Bruce Pascoe’s Earth, an Indigenous Ecological Allegory DAVID MICHAEL FONTEYN University of New South Wales In this paper I coin the term ‘Indigenous ecological allegory’ and argue that the 2001 novel, Earth, by the Indigenous Australian writer Bruce Pascoe (a Bunurong man) is an example. To come to this term, I first combine Maureen Quilligan’s outline of allegorical structure and function with post-colonial theories of allegory and the notion of interpolation. Similar to the way in which colonised characters interpolate the dominant discourses of the colonial culture in post-colonial allegory (in what I am calling ecological allegories) Nature, in personified form, interpolates the realist structure of the narrative. So, what I am calling an indigenous ecological allegory is one in which this personified Nature is based upon an Indigenous people’s worldview.1 Pascoe’s novel encodes such an indigenous worldview of nature in the word Country.2 Debbie Bird Rose explains the term Country: Country in Aboriginal English is not only a common noun but also a proper noun. People talk about country in the same way they would talk about a person: they speak to country, sing to country, visit country, worry about country, feel sorry for country, and long for country. People say that country knows, hears, smells, takes notice, takes care, is sorry or happy .