Studying Cranial Vault Modifications in Ancient Mesoamerica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Native Peoples of North America

Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins SUNY Potsdam Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins 2013 Open SUNY Textbooks 2013 Susan Stebbins This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library (IITG PI) State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 Cover design by William Jones About this Textbook Native Peoples of North America is intended to be an introductory text about the Native peoples of North America (primarily the United States and Canada) presented from an anthropological perspective. As such, the text is organized around anthropological concepts such as language, kinship, marriage and family life, political and economic organization, food getting, spiritual and religious practices, and the arts. Prehistoric, historic and contemporary information is presented. Each chapter begins with an example from the oral tradition that reflects the theme of the chapter. The text includes suggested readings, videos and classroom activities. About the Author Susan Stebbins, D.A., Professor of Anthropology and Director of Global Studies, SUNY Potsdam Dr. Susan Stebbins (Doctor of Arts in Humanities from the University at Albany) has been a member of the SUNY Potsdam Anthropology department since 1992. At Potsdam she has taught Cultural Anthropology, Introduction to Anthropology, Theory of Anthropology, Religion, Magic and Witchcraft, and many classes focusing on Native Americans, including The Native Americans, Indian Images and Women in Native America. Her research has been both historical (Traditional Roles of Iroquois Women) and contemporary, including research about a political protest at the bridge connecting New York, the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation and Ontario, Canada, and Native American Education, particularly that concerning the Native peoples of New York. -

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Chichen Itza Coordinates: 20°40ʹ58.44ʺN 88°34ʹ7.14ʺW From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chichen Itza ( /tʃiːˈtʃɛn iːˈtsɑː/;[1] from Yucatec Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza* Maya: Chi'ch'èen Ìitsha',[2] "at the mouth of the well UNESCO World Heritage Site of the Itza") is a large pre-Columbian archaeological site built by the Maya civilization located in the northern center of the Yucatán Peninsula, in the Municipality of Tinúm, Yucatán state, present-day Mexico. Chichen Itza was a major focal point in the northern Maya lowlands from the Late Classic through the Terminal Classic and into the early portion of the Early Postclassic period. The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, from what is called “In the Mexican Origin” and reminiscent of styles seen in central Mexico to the Puuc style found among the Country Mexico Puuc Maya of the northern lowlands. The presence of Type Cultural central Mexican styles was once thought to have been Criteria i, ii, iii representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary Reference 483 (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/483) interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya Region** Latin America and the Caribbean styles more as the result of cultural diffusion. Inscription history The ruins of Chichen Itza are federal property, and the Inscription 1988 (12th Session) site’s stewardship is maintained by Mexico’s Instituto * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list) Institute of Anthropology and History, INAH). The ** Region as classified by UNESCO. -

3569 A. Cucina 29 42.Qxd

JASs Invited Reviews Journal of Anthropological Sciences Vol. 83 (2005), pp. 29-42 Past, present and future itineraries in Maya bioarchaeology Andrea Cucina & Vera Tiesler Facultad de Ciencias Antropológicas, Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, km 1 Carretera Merida-Tizimin, 97305 Merida, Yucatán, Mexico; e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Summary – During the first half of the last century, studies of Maya skeletal remains gave emphasis mainly to head shaping and dental decoration, while little or no attention was bestowed to the ancient Maya’s skeletal biology and bioarchaeology. It was not until the late 1960’s and early 1970’s that more comprehensive approaches started visualizing this ancient society from its biological and cultural aspects by perceiving skeletal remains as a direct indicator of past cultural interactions. The recent growth in skeletal studies was also a natural consequence of the emergence of “bioarchaeology” as a specific discipline. From then on, increasing numbers of studies have been carried out, applying more and more sophisticated and modern techniques to the ancient Maya skeletal remains. This works attempts to briefly review the research history on Maya skeletal remains, from the pioneering works in the 1960’s to the development of more conscientious approaches based on theoretical, methodological and practical concepts in which the individual is the basic unit of biocultural analysis. Although, ecological issues and the biological evidence of social status differences still remain central cores in Maya bioarchaeology, new methodologically and topically oriented approaches have proliferated in the last years. They contribute to the development of a more complete, wide-angled view of the intermingled biological and cultural dynamics of a population that has not disappeared in the past and that continues to raise the interest of scholars and the public in general. -

2010 General Management Plan

Montezuma Castle National Monument National Park Service Mo n t e z u M a Ca s t l e na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t • tu z i g o o t na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t Tuzigoot National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior ge n e r a l Ma n a g e M e n t Pl a n /en v i r o n M e n t a l as s e s s M e n t Arizona M o n t e z u MONTEZU M A CASTLE MONTEZU M A WELL TUZIGOOT M g a e n e r a l C a s t l e M n a n a g e a t i o n a l M e n t M P o n u l a n M / e n t e n v i r o n • t u z i g o o t M e n t a l n a a t i o n a l s s e s s M e n t M o n u M e n t na t i o n a l Pa r k se r v i C e • u.s. De P a r t M e n t o f t h e in t e r i o r GENERAL MANA G E M ENT PLAN /ENVIRON M ENTAL ASSESS M ENT General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment MONTEZUMA CASTLE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND TUZIGOOT NATIONAL MONUMENT Yavapai County, Arizona January 2010 As the responsible agency, the National Park Service prepared this general management plan to establish the direction of management of Montezuma Castle National Monument and Tu- zigoot National Monument for the next 15 to 20 years. -

Mummies and Mummification Practices in the Southern and Southwestern United States Mahmoud Y

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications Natural Resources, School of 1998 Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States Mahmoud Y. El-Najjar Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan Thomas M. J. Mulinski Chicago, Illinois Karl Reinhard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard El-Najjar, Mahmoud Y.; Mulinski, Thomas M. J.; and Reinhard, Karl, "Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States" (1998). Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications. 13. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natresreinhard/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Karl Reinhard Papers/Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in MUMMIES, DISEASE & ANCIENT CULTURES, Second Edition, ed. Aidan Cockburn, Eve Cockburn, and Theodore A. Reyman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 7 pp. 121–137. Copyright © 1998 Cambridge University Press. Used by permission. Mummies and mummification practices in the southern and southwestern United States MAHMOUD Y. EL-NAJJAR, THOMAS M.J. MULINSKI AND KARL J. REINHARD Mummification was not intentional for most North American prehistoric cultures. Natural mummification occurred in the dry areas ofNorth America, where mummies have been recovered from rock shelters, caves, and over hangs. In these places, corpses desiccated and spontaneously mummified. In North America, mummies are recovered from four main regions: the south ern and southwestern United States, the Aleutian Islands, and the Ozark Mountains ofArkansas. -

Catálogo De Las Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales: Variantes Lingüísticas De México Con Sus Autodenominaciones Y Referencias Geoestadísticas

Lunes 14 de enero de 2008 DIARIO OFICIAL (Primera Sección) 31 INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE LENGUAS INDIGENAS CATALOGO de las Lenguas Indígenas Nacionales: Variantes Lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas. Al margen un logotipo, que dice: Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas. CATÁLOGO DE LAS LENGUAS INDÍGENAS NACIONALES: VARIANTES LINGÜÍSTICAS DE MÉXICO CON SUS AUTODENOMINACIONES Y REFERENCIAS GEOESTADÍSTICAS. El Consejo Nacional del Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas, con fundamento en lo dispuesto por los artículos 2o. de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos; 15, 16, 20 y tercero transitorio de la Ley General de Derechos Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas; 1o., 3o. y 45 de la Ley Orgánica de la Administración Pública Federal; 1o., 2o. y 11 de la Ley Federal de las Entidades Paraestatales; y los artículos 1o. y 10 fracción II del Estatuto Orgánico del Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas; y CONSIDERANDO Que por decreto publicado en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 14 de agosto de 2001, se reformó y adicionó la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, determinando el carácter único e indivisible de la Nación Mexicana y su composición pluricultural sustentada en sus pueblos indígenas. Que con esta reforma constitucional nuestra Carta Magna reafirma su carácter social, al dedicar un artículo específico al reconocimiento de los derechos de los pueblos indígenas. Que el artículo 2o. constitucional establece que “los pueblos indígenas son aquellos que descienden de poblaciones que habitaban en el territorio actual del país al iniciarse la colonización y que conservan sus propias instituciones sociales, económicas, culturales y políticas, o parte de ellas.” Que uno de los derechos de los pueblos y las comunidades indígenas que reconoce el apartado “A” del artículo 2o. -

1995-2006 Activities Report

WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS WITHOUT WILDLIFE M E X I C O The most wonderful mystery of life may well be EDITORIAL DIRECTION Office of International Affairs U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service the means by which it created so much diversity www.fws.gov PRODUCTION from so little physical matter. The biosphere, all Agrupación Sierra Madre, S.C. www.sierramadre.com.mx EDITORIAL REVISION organisms combined, makes up only about one Carole Bullard PHOTOGRAPHS All by Patricio Robles Gil part in ten billion [email protected] Excepting: Fabricio Feduchi, p. 13 of the earth’s mass. [email protected] Patricia Rojo, pp. 22-23 [email protected] Fulvio Eccardi, p. 39 It is sparsely distributed through MEXICO [email protected] Jaime Rojo, pp. 44-45 [email protected] a kilometre-thick layer of soil, Antonio Ramírez, Cover (Bat) On p. 1, Tamul waterfall. San Luis Potosí On p. 2, Lacandon rainforest water, and air stretched over On p. 128, Fisherman. Centla wetlands, Tabasco All rights reserved © 2007, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service a half billion square kilometres of surface. The rights of the photographs belongs to each photographer PRINTED IN Impresora Transcontinental de México EDWARD O. WILSON 1992 Photo: NASA U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL CONSERVATION WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS MEXICO ACTIVITIES REPORT 1995-2006 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE At their roots, all things hold hands. & When a tree falls down in the forest, SECRETARÍA DE MEDIO AMBIENTE Y RECURSOS NATURALES MEXICO a star falls down from the sky. CHAN K’IN LACANDON ELDER LACANDON RAINFOREST CHIAPAS, MEXICO FOREWORD onservation of biological diversity has truly arrived significant contributions in time, dedication, and C as a global priority. -

O Céano P a C Íf

A APIZACO 10 km F.C. A F.C. A PACHUCA F.C. A XALAPA A ENT. ALEJANDRO ESCOBAR NAPOLES A XALAPA 58 Km A POZA RICA 216 Km K 10 APIZACO B C CARR. 129 - 47 km D E F G H I J K 98 ° 00 ' 30 ' 97 ° 00 ' 30 ' Puente Nacional F.C. A 96 ° 00 ' 30 ' 95 ° 00' 30 ' 94 ° 00' HUAMANTLA MEX apan NAUTLA A 136 A XALAPA 98 Km PUENTE LA ANTIGUA A APIZACO 27 km 30 CUOTA - TOLL Huitzil Río Villa de Etla (San Pedro y San Pablo Etla) Latuvi R. 27 Reyes Etla 68 nillo Las Esperanzas Y L TLAXCALA za R. 35 6 San Agustín Etla El V Man Yuvila Gua A San Andrés Zautla San José Etla R. Arco Laguna N. Etla EST. 31 camayas 67 MOGOTE E.M.O. La M C Totolcingo VERACRUZ Cumbre Las Vigas TABLA DE DISTANCIAS APROXIMADAS. Para obtener la distancia entre dos poblaciones por carretera Sto. Tomás Mazaltepec 1 pavimentada deberá encontrarse en el índice alfabético losX números correspondientes a cada una de ellas. 101 MEX Soledad Etla MEX 140 60 Gpe. Etla En el grupo encabezado por el número menorA ( Rojo), se buscará el número mayor (Negro), a cuya derecha 125 Llano Grande L MEX Stgo. Etla C se índica la distanciaT aproximada (Negro) en Kilómetros Ejemplo:Oaxaca (10 ) a Tuxtepec (19) es de 221 - PARQUE NACIONAL B. JUÁREZ 119 16 Sta. Cruz El Estudiante Kms. (En la columna 10 se busca el 19 y se lee 221 ) 42 Guadalupe Hidalgo Tierra Colorada 40 Jamapa San Pablo Etla 1.-Asunción Nochixtlán 8.-Miahuatlán de Porfirio Díaz 15.-Sn. -

Toward a Dakota Literary Tradition: Examining Dakota Literature Through the Lens of Critical Nationalism

Toward a Dakota Literary Tradition: Examining Dakota Literature through the Lens of Critical Nationalism by Sarah Raquel Hernandez B.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2005 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2016 This thesis entitled: Toward a Dakota Literary Tradition: Examining Dakota Literature through the Lens of Critical Nationalism written by Sarah Raquel Hernandez has been approved for the Department of English Penelope Kelsey, Committee Chair Cheryl Higashida, Committee Member Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Abstract Hernandez, Sarah Raquel (Ph.D., English) Toward a Dakota Literary Tradition: Examining Dakota Literature through the Lens of Critical Nationalism Thesis Directed by Professor Penelope Kelsey Dakota literature is often regarded as an extinct and thus irrelevant oral storytelling tradition by EuroAmerican, and at times, Dakota people. This dissertation disputes this dominant view and instead argues that the Dakota oral storytelling tradition is not extinct, but rather has been reimagined in a more modern form as print literature. In this dissertation, I reconstruct a genealogy of the Dakota literary tradition that focuses primarily (but not exclusively) upon the literary history of the Santee Dakota from 1836 to present by analyzing archival documents – Dakota orthographies, Dakota mythologies, and personal and professional correspondences – to better understand how this tradition has evolved from an oral to a written form. -

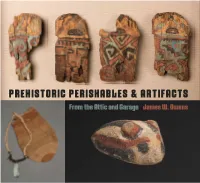

Prehistoric Perishables & Artifacts

PREHISTORIC PERISHABbES I ARTIFACTS Permission to copy images denied without written approval. PREHISTORIC PERISHABLES & ARTIFACTS Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 1 6/28/19 10:54 AM Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 2 6/28/19 10:54 AM PREHISTORIC PERISHABLES & ARTIFACTS From the Attic and Garage JAMES W. OWENS Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 3 6/28/19 10:54 AM Privately published by James W. Owens Albuquerque, New Mexico and Casper, Wyoming Copyright © !"#$ James W. Owens %&& '()*+, '-,-'.-/ Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 4 6/28/19 10:54 AM Dedicated to Clifford A. Owens 0%+*-' Elaine Day Stewart 12+*-' Helen Snyder Owens ,+-312+*-' Without whom this book would not have been possible. Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 5 6/28/19 10:54 AM Permission to copy images denied without written approval. jimowens_REV2_finalpp_6.27.19.indd 6 6/28/19 10:54 AM CONTENTS Preface ix %//(+(2;%& (+-1, : Acknowledgments xii Jewelry ##6 Location, Location, Location # %//(+(2;%& (+-1, < Hohokam #76 /(,3&%4 5%,- # Painted Objects 6 %//(+(2;%& (+-1, $ Hogup Cave #97 /(,3&%4 5%,- ! Hunting Objects !7 %//(+(2;%& (+-1, #" Fremont #:: /(,3&%4 5%,- 7 Cache Pots and Cradleboard 8# %//(+(2;%& (+-1, ## Baskets #<$ /(,3&%4 5%,- 8 Footwear and Accessories 9# %//(+(2;%& (+-1, #! Various Items !": /(,3&%4 5%,- 6 Fremont Items :: %//(+(2;%& (+-1, #7 Pottery !77 /(,3&%4 5%,- 9 Ceremonial Objects $$ Bibliography !67 Permission to copy images denied without written approval. -

Bibliography of Health Issues Affecting North American Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts: 1950-1988

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 357 923 RC 019 183 AUTHOR Owens, Mitchell V., Comp.; And Others TITLE Bibliography of Health Issues Affecting North American Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts: 1950-1988. INSTITUTION Indian Health Service (PHS/HSA), Rockville, MD. PUB DATE [90] NOTE 275p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Alaska Natives; *American Indian Education; *American Indians; Canada Natives; Delivery Systems; *Diseases; Elementary Secondary Education; *Health; health Education; Health Programs; Health Services; Higher Education; Medical Education; *Medicine; Nutrition IDENTIFIERS Native Americans ABSTRACT This bibliography of 2,414 journal articles provides health professionals and others with quick referenceson health and related issues of American Indians and Alaska Natives. The citations cover articles published in U.S. and Canadian medical and health-related journals between 1950 and 1988. Five sectionsdeal with major health categories and are divided into further subcategories. The first section, "Social and Cross-CulturalAspects of Health and Disease," covers traditional health practices; archeology, demography, and anthropology; food, nutrition, and related disorders; pregnancy, family planning, and relatedproblems; health and disease in infancy and childhood; aging (including geriatric programs); and psychology and acculturation.The next section, "Health, Health Education, and Health Care Delivery" includes general aspects of health and disease, healthand dental care delivery, -

Myth and Model. the Pattern of Migration, Settlement, and Reclamation of Land in Central Mexico and Oaxaca

Myth and Model. The Pattern of Migration, Settlement, and Reclamation of Land in Central Mexico and Oaxaca Viola König Ethnologisches Museum – Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, Germany [email protected] Abstract: A comparison of the documentation in the pre-Hispanic and early colonial pic- torials and written texts from Central Mexico, Oaxaca and in between, shows parallels and a specic model for the settlement and the legitimation of land ownership. Migration from a mythic place of origin is followed by choice of the new homeland, which is ocially conrmed by the act of inauguration, i.e. a New Fire ceremony. Population growth leads to either the abandonment of a village or exodus of smaller groups, thus starting a new migration. e same procedure begins. e Mixtecs started as early as in the Classic period to migrate to Teotihuacan and later to Mexico Tenochtitlan as immigrant workers. ey were the rst to leave their Mixtec home- land in the 1970ies traveling to the USA and Canada. Today, Mixtec communities can be found in Manhattan and all over California. Keywords: migration; settlement; land ownership; Mixtec codices; pre-Hispanic and early colonial periods. Resumen: Una comparación de la documentación en los textos pictóricos y escritos pre- hispánicos y coloniales tempranos del centro de México, Oaxaca y las regiones intermedias, muestra paralelos y revela un modelo especíco para los procesos de asentamiento y la legi- timación de la propiedad de la tierra. La migración desde un lugar de origen mítico es seguida por la elección de un nuevo lugar de asentamiento, conrmada por un acto de inauguración, es decir, la ceremonia del Fuego Nuevo.