Namibia, 1 LEGACIES of COLONIALISM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Consolidated Diamond Mines and the Natives in Colonial Namibia

THE CONSOLIDATED DIAMOND MINES AND THE NATIVES IN COLONIAL NAMIBIA A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ROLE OF ILLEGAL DIAMONDS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF OWAMBOLAND (1908 - 1990) A DISSERTATION IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA BY JOB SHIPULULO KANANDJEMBO AMUPANDA 200614215 MAIN SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR LESLEY BLAAUW UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA CO-SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDRE DU PISANI UNIVERSITY OF NAMIBIA MARCH 2020 ii Abstract Whilst the ‘natural resource curse’ theory has been an enduring theory in the study of the relationship between natural resources endowment and economic development, the economics approach to this theory, which privileges the economic explanation focusing on the Dutch disease and revenue volatility, has been dominant. The political economy approach has proven to be more useful not only in political science but also in the study of the African political economy and developing countries such as Namibia where the political conditions played an influential role than the Dutch disease and revenue volatility. At the theoretical level, this study aligns and pursued the political economy approach to the ‘natural resource curse’ research and provides further explanations from a decolonial perspective. The decolonial explanations are useful for it is evident that the ‘natural resource curse’, as is the case with other Eurocentric theories, does not dwell on the agency and subjectivity of the natives, in this case those involved in the illegal diamond trade. Because of the political conditions in colonial Namibia, the political economy explanations such as rent-seeking, agency and moral cosmopolitanism are insufficient in explaining the relationship between the natives and CDM in colonial Namibia in general and the role of illegal diamonds in the development of Owamboland in particular. -

Kolmanskop, Comme Un Mirage Kolmanskop, Like a Miracle

OUT OF AFRICA KOLMANSKOP, COMME UN MIRAGE KOLMANSKOP, LIKE A MIRACLE STORY AND PHOTOS BY YANN MACHEREZ We love ! « LE SOLEIL EST ENCORE HAUT DANS LE CIEL, MON CORPS SE COURBE SOUS LA CHA- u beau milieu des étendues sèches et stériles du En s’installant à quelques kilomètres de Lüderitz au début du LEUR ÉTOUFFANTE. DEVANT MOI, ENCORE UNE CENTAINE DE MÈTRES DE CHEMIN DE désert du Namib reposent les fondations d'une ville siècle dernier, les premiers habitants de Kolmanskop ne se FER À INSPECTER. UNE PIERRE PLUS SCINTILLANTE QUE LES AUTRES ATTIRE ALORS MON Ajadis flamboyante. doutaient pas de la richesse qui se trouvait sous leurs pieds… REGARD, JE ME BAISSE POUR LA RÉCUPÉRER. Sur les douces courbes des dunes émergent les vestiges ru- littéralement! gueux de Kolmanskop, une ville fantôme autrefois capitale En effet, il suffisait de se baisser pour ramasser les diamants MON NOM EST ZACHARIAS LEWALA ET JE N’IMAGINAIS PAS UN SEUL INSTANT QUE mondiale du diamant. à la main, à même le sol. CETTE DÉCOUVERTE ALLAIT CHANGER LE DESTIN DE TOUTE UNE RÉGION ». Aujourd’hui, il parait difficile d’imaginer que ces baraquements déla- C’est ce qui arriva le 08 avril 1908 à Zacharias Lewala. brés abritaient l'une des communautés les plus prospères au monde. 14 I HAMAJI HAMAJI I 15 Avant la fièvre du diamant, Kolmanskop était une petite ville sud, une usine à glace et même une salle de bal ou venaient insignifiante. Si insignifiante que l’origine de son nom provient se produire les plus grands opéras européens. -

German Colonial Heritage in Africa – Artistic and Cultural Perspectives German Colonial Heritage in Africa – Artistic and Cultural Perspectives Contents

1 GERMAN COLONIAL HERITAGE IN AFRICA – ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES GERMAN COLONIAL HERITAGE IN AFRICA – ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES CONTENTS About this report ..........................................................................................Page 1 Daniel Stoevesandt and Fabian Mühlthaler German Colonial Heritage in Burundi: From a Cultural Production Perspective ...................................................Page 5 Freddy Sabimbona The Correlation Between Artistic Productions in Cameroon and the Discourse on Decolonisation ........................................................Page 11 Dzekashu MacViban From Periphery to Focus (and Back Again?) The Topic of Colonialism in Cultural Productions in Germany ...............Page 21 Fabian Lehmann This publication is commissioned by the Goethe-Instituts in Sub-Saharan Africa Critical Refection on Cultural Productions Regarding German Colonialism in and Around Namibia ...........................................Page 35 edited by Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja Edited by Goethe-Institut Kamerun www.goethe.de/kamerun and Cultural Productions with reference to Colonial History ........................Page 47 Goethe-Institut Namibia Ngangare Eric www.goethe.de/namibia cover image German Colonial Heritage in Tanzania: Maji Maji Flava, © N. Klinger A Survey on Artistic Productions ................................................................Page 53 Vicensia Shule graphic design and layout Turipamwe Design, Windhoek, Namibia www.turipamwedesign.com Cultural Productions with -

EUI Working Papers

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2009/40 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES TRANSNATIONAL MOVEMENTS BETWEEN COLONIAL EMPIRES: MIGRANT WORKERS FROM THE BRITISH CAPE COLONY IN THE GERMAN DIAMOND TOWN LÜDERITZBUCHT Ulrike Lindner EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES Transnational movements between colonial empires: Migrant workers from the British Cape Colony in the German diamond town Lüderitzbucht ULRIKE LINDNER EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2009/40 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the EUI if the paper will be published elsewhere and also take responsibility for any consequential obligation(s). ISSN 1028-3625 © 2009 Ulrike Lindner Printed in Italy, August 2009 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, is home to a large post-doctoral programme. Created in 1992, it aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. -

Black Pastoralists, White Farmers

Black pastoralists, white farmers: The dynamics of land dispossession and labour recruitment in Southern Namibia 1915 - 1955 by Jeremy Gale Silvester A Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London July, 1993. 1 ProQuest Number: 11010539 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010539 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 tiOCIVo^ ?a/us ^ ABSTRACT. The dissertation examines the dynamics of rural economic struggle within the reserves and on white commercial farms. The supply of farm labour during the period 1915-1955 can be seen as an equation with a number of variables. Black pastoral communities in southern Namibia sought to retain control over their land and their labour. In contrast, the administration sought the division of land amongst a new wave of white immigrants and the recruitment of local black pastoralists as farm labourers. The ‘state apparatus’ available to enforce legislation in the early years of South African rule was initially weak and local labour control depended largely on the relationship between individual farmers and their workforce. -

German Colonial History in Africa

1 GERMAN COLONIAL HERITAGE IN AFRICA – ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES GERMAN COLONIAL HERITAGE IN AFRICA – ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES CONTENTS About this report ..........................................................................................Page 1 Daniel Stoevesandt and Fabian Mühlthaler German Colonial Heritage in Burundi: From a Cultural Production Perspective ...................................................Page 5 Freddy Sabimbona The Correlation Between Artistic Productions in Cameroon and the Discourse on Decolonisation ........................................................Page 11 Dzekashu MacViban From Periphery to Focus (and Back Again?) The Topic of Colonialism in Cultural Productions in Germany ...............Page 21 Fabian Lehmann This publication is commissioned by the Goethe-Instituts in Sub-Saharan Africa Critical Reflection on Cultural Productions Regarding German Colonialism in and Around Namibia ...........................................Page 35 edited by Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja Edited by Goethe-Institut Kamerun www.goethe.de/kamerun and Cultural Productions with reference to Colonial History ........................Page 47 Goethe-Institut Namibia Ngangare Eric www.goethe.de/namibia cover image German Colonial Heritage in Tanzania: Maji Maji Flava, © N. Klinger A Survey on Artistic Productions ................................................................Page 53 Vicensia Shule graphic design and layout Turipamwe Design, Windhoek, Namibia www.turipamwedesign.com Cultural Productions with -

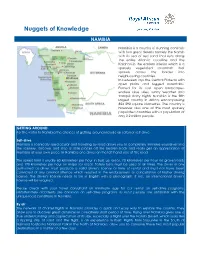

Nuggets of Knowledge

Nuggets of Knowledge NAMIBIA Namibia is a country of stunning contrasts with two great deserts namely the Namib with its sea of red sand that runs along the entire Atlantic coastline and the Kalahari in the eastern interior which is a sparsely vegetated savannah that sprawls across the border into neighbouring countries. In-between lays the Central Plateau with open plains and rugged mountains. Famed for its vast open landscapes, endless blue skies, sunny weather and tranquil starry nights Namibia is the fifth largest country in Africa, encompassing 824 292 square kilometres. The country is however also one of the most sparsely populated countries with a population of only 2.2 million people. GETTING AROUND For the visitor to Namibia the choices of getting around include air safari or self-drive. Self-drive Namibia is scenically spectacular and traveling by road allows you to completely immerse yourselves into the scenery, discover and stop at little places off the beaten track and really get an appreciation of Namibia at your own pace. In Namibia one drives on the left hand side of the road. The speed limit is usually 60 kilometres per hour in built up areas, 70 kilometres per hour on gravel roads and 120 kilometres per hour on major tar roads. Safety belts must be used at all times. The driver or any authorized co-driver must produce a valid driver’s license at time of rental and must not have been convicted of any criminal offence which resulted in the endorsement or cancellation of his/her driving license. -

Reflections on Music and Deutschtum in Namibia

Reflections on Music and Deutschtum in Namibia Deborah Lynn van Zyl Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Stephanus Muller December 2016 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Plagiarism Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the authorship owner thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature: D.L. van Zyl Date: December 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This thesis examines music-making through the lens of Deutschtum and the construction of a Heimat in South West Africa/Namibia. The research is concerned with how German musicking took root in German colonial life, and the role of musicking in establishing and cementing German culture in South West Africa/Namibia thereafter. The thesis documents the German presence in South West Africa/Namibia from the arrival of the German missionaries to the establishment of a German colony, through the mandate years including two world wars, until after independence in 1990. A summary of the topography and demography, with emphasis on the towns of Swakopmund and Lüderitz, as well as music activities in the prisoner of war camps of both World Wars, serve as case studies to delve into the role of music in creating a sense of settledness. -

Mining Journal Supplement in October 1992

Namibia: Abundant COUNTRY Exploration SUPPLEMENT Opportunities able to exploration companies. This new supplement provides the international finan- cial and exploration community with a re- view of the progress and success achieved over the last five years, and of the opportu- nities awaiting potential investors in this dynamic and geologically prospective coun- try. Situated in the western half of the south- ern African subcontinent, Namibia encom- passes an area of over 824,000 km². It has a hot and dry climate. Rainfall is extremely variable, ranging from less than 200 mm in the south to about 800 mm in the northeast. With less than 50 mm average annual rain- fall, the coastal Namib Desert is one of the DebMarine diamond recovery vessel. Offshore diamond most arid places on Earth. Only the Kunene, recovery is set to increase its share of total output Okavango, Zambezi and Chobe/Linyanti rivers, along Namibia's northern border, and Namibia is currently developing one of southern Afri- the Orange River, which forms the south- ca's most dynamic mineral industries, a trend that is set to ern frontier, are perennial. The Kalahari continue well into the next century. Since 1992, explora- Desert, with an average rainfall of less than tion expenditure has increased by more than 500%, and 200 mm, extends over the eastern part of today more than 60 companies are actively exploring the the country, bordering Botswana and South exciting potential of Namibia's mineral sector. Recent ex- Africa. It is separated from the Namib by a ploration and investment initiatives have already led to high inland plateau that reaches elevations the proposed development of two major base metal of over 2,000 m and is covered by shrub projects at a cost of over US$750 million; these will more and mixed tree savannah. -

Exploring Namibia-Classic(Edited)

P a g e | 1 Exploring Namibia-Classic(Edited) P a g e | 2 P a g e | 3 P a g e | 4 Exploring Namibia-Classic(Edited) Mariental - Fish River Canyon - Luderitz - Sossusvlei - Swakopmund - Damaraland - Etosha South - Etosha East - Windhoek 15 Days / 14 Nights Reference: SOAN-EN Date of Issue: 24 July 2019 Click here to view your Digital Itinerary P a g e | 5 Introduction Accommodation Type Destination Basis Duration Camelthorn Kalahari Lodge Mariental B&B 1 Night Canyon Village Gondwana Collection Namibia Fish River Canyon B&B 1 Night Luderitz Nest Hotel Luderitz B&B 2 Nights Namib Desert Lodge Gondwana Collection Sossusvlei B&B 2 Nights Namibia Swakopmund Plaza Hotel Swakopmund B&B 2 Nights → The Beach Hotel alternate Damara Mopane Lodge Gondwana Collection Damaraland B&B 2 Nights Namibia Etosha Safari Camp Gondwana Collection Etosha South B&B 2 Nights Namibia Mokuti Etosha Lodge Etosha East B&B 1 Night River Crossing Lodge Windhoek B&B 1 Night Key B&B: Bed and Breakfast Day 1: Camelthorn Kalahari Lodge, Mariental Mariental Situated in south central Namibia, fringing the Kalahari Desert, the city of Mariental lies along the TransNamib railway and serves as the Hardap Region’s commercial and administrative capital. It provides an important petrol stop before heading west to Sesriem to view the red-orange dunes of Sossusvlei. Mariental is located close to magnificent the Hardap Dam, which is the largest reservoir in Namibia. The Hardap Irrigation Scheme has breathed life into this arid terrain, which is now fertile with farmlands covered in citrus, melons, lucerne, wine and maize, and dotted with ostrich farms. -

Tender for Tourism Concessions

REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FORESTRY & TOURISM Tender for Tourism Concessions Inside Tsau //Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park The Tsau //Khaeb (Sperrgebiet) National Park National Park is located in the south-western corner of Namibia. The following concession opportunities are available within the Tsau //Khaeb National Park (TKNP) tourism development areas (TDAs). The Ministry of Environment, Forestry & Tourism invites interested parties to register for the tender process and obtain the Request for Proposal (RFP) document. Bidder registration is compulsory to qualify for tendering and no registration will be allowed after the close of the registration period. CONCESSION TITLE DESCRIPTION OF CONCESSION CONCESSION RIGHTS & ACTIVITIES Northern Sand & Sea The Concession covers the area of the TKNP north of Lüderitz and is bordered on the west by the Atlantic Ocean • 1 or 2-day guided 4x4 desert dune drives and coastal adventure safaris and to the north and east by the Namib Naukluft National Park. • Overnight camping in mobile camps at Dagger Rocks and Douglas Bay • Guided mining village history tours • Guided quad bike trails • Guided sandboarding • Guided off-shore angling (provided necessary permits are obtained) and Island Tours within the rules and regulations of the Sea Fisheries Act Lüderitz Peninsula The Concession covers the entire Peninsula which is situated directly south of Lüderitz. The south-eastern road 60-bed resort at Griffith Bay offering linking the entrance gate at the southern tip of the lagoon with -

A History of Diamonds Through Philately: the Frank Friedman Collection

NOTES & NEW TECHNIQUES A HISTORY OF DIAMONDS THROUGH PHILATELY: THE FRANK FRIEDMAN COLLECTION Stuart D. Overlin the hobby as “the poor man’s way to collect gems” (Fried man, 2007). He joined the Johannes burg South African jeweler Frank Friedman’s collec- Philatelic Society to learn more and began to acquire tion of diamond-themed stamps and other postal pieces. His collection now totals approximately material offers an illuminating visual record of 2,000 items from more than 36 countries. In addi- diamond history. Comprising approximately tion to stamps, it contains rare postcards, cancella- 2,000 pieces, these items chronicle diamond for- tion marks, historical letters, and original artists’ mation, the history of mining and manufactur- renderings of stamp and cancellation designs. ing, and the evolution of a science and an indus- Mr. Friedman has displayed his collection inter- try built around this remarkable gemstone. nationally on several occasions. In 1989 it was show- cased in the Harry Oppenheimer Museum at the Israeli Diamond Center in Ramat Gan. In June 1997, hilately, the collecting of stamps and other it was the keynote exhibit at the Vicenza Trade Fair postal material, first became popular with the (Weil, 1997). Awards include a gold medal at the introduction of the British penny and two- 2006 World Philatelic Exhibition in Washington P (“Stamp of approval,” 2006), a 2008 silver medal at penny adhesive stamps in 1840. Much of the hobby’s attraction lies in the range of fascinating subjects the World Stamp Championship in Israel, and a large that have been documented. Diamonds have vermeil medal at the 26th Asian International Stamp appeared in postage stamps, special cancellation Exhibition (Joburg 2010).