Black Pastoralists, White Farmers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GUIDE to CIVIL SOCIETY in NAMIBIA 3Rd Edition

GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA GUIDE TO 3Rd Edition 3Rd Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono and Naita Marowa PJ Rejoice Compiled by GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA 3rd Edition AN OVERVIEW OF THE MANDATE AND ACTIVITIES OF CIVIL SOCIETY ORGANISATIONS IN NAMIBIA Compiled by Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono GUIDE TO CIVIL SOCIETY IN NAMIBIA COMPILED BY: Rejoice PJ Marowa and Naita Hishoono PUBLISHED BY: Namibia Institute for Democracy FUNDED BY: Hanns Seidel Foundation Namibia COPYRIGHT: 2018 Namibia Institute for Democracy. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means electronical or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission of the publisher. DESIGN AND LAYOUT: K22 Communications/Afterschool PRINTED BY : John Meinert Printing ISBN: 978-99916-865-5-4 PHYSICAL ADDRESS House of Democracy 70-72 Dr. Frans Indongo Street Windhoek West P.O. Box 11956, Klein Windhoek Windhoek, Namibia EMAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.nid.org.na You may forward the completed questionnaire at the end of this guide to NID or contact NID for inclusion in possible future editions of this guide Foreword A vibrant civil society is the cornerstone of educated, safe, clean, involved and spiritually each community and of our Democracy. uplifted. Namibia’s constitution gives us, the citizens and inhabitants, the freedom and mandate CSOs spearheaded Namibia’s Independence to get involved in our governing process. process. As watchdogs we hold our elected The 3rd Edition of the Guide to Civil Society representatives accountable. -

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

The Main Vegetation Types of Kaokoland, Northern Damaraland and a Description of Some Transects of Owambo, Etosha and North Western South West Africa

THE MAIN VEGETATION TYPES OF KAOKOLAND, NORTHERN DAMARALAND AND A DESCRIPTION OF SOME TRANSECTS OF OWAMBO, ETOSHA AND NORTH WESTERN SOUTH WEST AFRICA Rui Ildegario de Sousa Correia June 1976 ~ € id Tdi MAIN VEGETATION TYPES OF KAOKOLAND, NORTHERN DAMARALAND AND A DESCRIPTION OF SOME TRANSECTS OF OWAMBO, ETOSHA AND NORTH WESTERN SOUT WEST AFRICA The general ecological conditions that influence the vege- tation types of the study area have already been described in a previous report. The main factor influencing vegetation here, is rainfall. Topography plays a very important paralel role related with an additional distribution of rainwater by the superficial drainage of hills and mountains to the neighbouring flats " and slopes. Concerning the soils, it appears that the physical structure is of more importance than the chemical composition, as this (the structure) determines the availability of water for root development. - Iu some specific instances the soil seems to have a marked effect on the vegetation such as the superficial calcareous layer in south-eastern Kaokoland. The influence of the watersheds is also well marked in deter- mining vegetation types, whether floristic or physiognomic. In addition both physiognomic features and floristic composi- tion have been used to determine the boundaries of the various vegetation types as described. Judicious use/..... ‘co Judicious use was also made of "indicator" species, whether by its occurence or by its absence. The following have been used-<« Baikeea plurijuga - Typical of red “alahari sands in the me~- dian and higher rainfall areas (300 - 700 mm/2),“- Spirostachys africane - Usually appears on the edge of pans (such as Owambo and Southern Angola) and along seasonal rockey c : or sandy dry water courses exept in the desert country courses. -

Directions from Noordoewer to Sossusvlei Lodge (Via Grünau, Keetmanshoop, Mariental, Maltahöhe & Hammerstein)

Directions from Noordoewer To Sossusvlei Lodge (via Grünau, Keetmanshoop, Mariental, Maltahöhe & Hammerstein) There are a number of alternative routes to follow from the South African - Namibian border to Sossusvlei Lodge. However, the route described below makes optimum use of good asphalt surfaced roads and allows one to travel at the maximum speed of 120 kilometres per hour for a greater distance. The average maximum recommended speed over gravel surfaces is 80 kilometres per hour. Total Distance : 805 Kilometres Road Legend : Average Duration : ±8 Hours B = Major Route (Asphalt) Road Surfaces : Asphalt – 530 kms C = Minor Road (Gravel) Gravel – 275 kms D = District Road (Gravel) o Once you have passed through the South African (Vioolsdrif) and Namibian (Noordoewer) custom posts on either side of the Orange River, leave Noordoewer on the B1 North. o Travel for 139 kilometres to Grünau and then a further 163 kilometres on the B1 to Keetmanshoop. This is a major town en-route and a stop here is recommended. Refuel, stretch the legs and obtain refreshments. o Please note that not all refuelling points indicated on the local maps at small towns are always still there or have fuel available. Always stay on the safe side and refuel at major towns along the way. o Continue on the B1 for another 217 kilometres past Tses, Asab and Gibeon turn-off to just before the town of Mariental. Turn left onto the C19 at the Maltahöhe intersection (T- junction). If you are not sure of your fuel status, rather continue on to Mariental at this point and refuel there. -

Local Authority Elections Results and Allocation of Seats

1 Electoral Commission of Namibia 2020 Local Authority Elections Results and Allocation of Seats Votes recorded per Seats Allocation per Region Local authority area Valid votes Political Party or Organisation Party/Association Party/Association Independent Patriots for Change 283 1 Landless Peoples Movement 745 3 Aranos 1622 Popular Democratic Movement 90 1 Rally for Democracy and Progress 31 0 SWANU of Namibia 8 0 SWAPO Party of Namibia 465 2 Independent Patriots for Change 38 0 Landless Peoples Movement 514 3 Gibeon 1032 Popular Democratic Movement 47 0 SWAPO Party of Namibia 433 2 Independent Patriots for Change 108 1 Landless People Movement 347 3 Gochas 667 Popular Democratic Movement 65 0 SWAPO Party of Namibia 147 1 Independent Patriots for Change 97 1 Landless peoples Movement 312 2 Kalkrand 698 Popular Democratic Movement 21 0 Hardap Rally for Democracy and Progress 34 0 SWAPO Party of Namibia 234 2 All People’s Party 16 0 Independent Patriots for Change 40 0 Maltahöhe 1103 Landless people Movement 685 3 Popular Democratic Movement 32 0 SWAPO Party of Namibia 330 2 *Results for the following Local Authorities are under review and will be released as soon as this process has been completed: Aroab, Koës, Stampriet, Otavi, Okakarara, Katima Mulilo Hardap 2 Independent Patriots for Change 180 1 Landless Peoples Movement 1726 4 Mariental 2954 Popular Democratic Movement 83 0 Republican Party of Namibia 59 0 SWAPO Party of Namibia 906 2 Independent Patriots for Change 320 0 Landless Peoples Movement 2468 2 Rehoboth Independent Town -

Namibia Starline Timetable

TRAIN : WINDHOEK – GOBABIS – WINDHOEK TRAIN : WINDHOEK – OTJIWARONGO – WINDHOEK TRAIN NO 9903 TRAIN NO 9904 TRAIN NO 9966 TRAIN NO 9915 TIMETABLE DAYS MON, DAYS MON, MONDAYS MONDAY WED, FRI WED, FRI WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS Windhoek D 05:50 Gobabis D 14:50 Windhoek D 15:45 Otjiwarongo D 15:40 Hoffnung D 06:55 Witvlei D 16:14 Okahandja A 18:00 Omaruru A 18:30 Neudamm D 07:35 Omitara A 17:52 D 18:05 D 19:30 Omitara A 10:10 D 17:56 Karibib D 20:40 Kranzberg A 21:10 D 10:12 Neudamm D 20:36 Kranzberg A 21:20 D 21:50 Witvlei D 11:53 Hoffnung D 21:18 D 21:40 Karibib D 22:20 Gobabis A 13:25 Windhoek A 22:25 Omaruru A 23:00 Okahandja A 01:30 D 23:35 D 01:40 Otjiwarongo A 02:20 Windhoek A 03:20 TRAIN : WINDHOEK – WALVIS BAY – WINDHOEK TRAIN: WALVIS BAY–OTJIWARONGO–WALVIS BAY EFFECTIVE FROM TRAIN NO 9908 TRAIN NO 9909 TRAIN NO 9901 / 9912 TRAIN NO 9907 / 9900 DAYS DAILY DAYS DAILY MONDAY MONDAY MONDAY 21 JANUARY 2008 EXCEPT EXCEPT WEDNESDAY WEDNESDAY SAT SAT FRIDAY FRIDAY STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS STATIONS Business Hours : Windhoek Central Reservations : Monday – Friday 07:00 to 19:00 Tel. (061) 298 2032/2175 Windhoek D 19:55 Walvis Bay D 19:00 Otjiwarongo D 14:40 Walvis Bay D 14:20 Saturdays 07:00 to 09:30 Fax (061) 298 2495 Okahandja A 21:55 Kuiseb D 19:20 Omaruru A 17:30 Kuiseb D 14:30 Sundays 15:30 to 19:00 D 22:05 Swakopmund A 20:35 D 18:30 Swakopmund A 15:50 Website : www.transnamib.com.na Karibib D 00:40 D 20:45 Kranzberg A 19:55 D 16:00 StarLine Information : E-mail : [email protected] Kranzberg -

The Role and Application of the Union Defence Force in the Suppression of Internal Unrest, 1912 - 1945

THE ROLE AND APPLICATION OF THE UNION DEFENCE FORCE IN THE SUPPRESSION OF INTERNAL UNREST, 1912 - 1945 Andries Marius Fokkens Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Military Science (Military History) at the Military Academy, Saldanha, Faculty of Military Science, Stellenbosch University. Supervisor: Lieutenant Colonel (Prof.) G.E. Visser Co-supervisor: Dr. W.P. Visser Date of Submission: September 2006 ii Declaration I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously submitted it, in its entirety or in part, to any university for a degree. Signature:…………………….. Date:………………………….. iii ABSTRACT The use of military force to suppress internal unrest has been an integral part of South African history. The European colonisation of South Africa from 1652 was facilitated by the use of force. Boer commandos and British military regiments and volunteer units enforced the peace in outlying areas and fought against the indigenous population as did other colonial powers such as France in North Africa and Germany in German South West Africa, to name but a few. The period 1912 to 1945 is no exception, but with the difference that military force was used to suppress uprisings of white citizens as well. White industrial workers experienced this military suppression in 1907, 1913, 1914 and 1922 when they went on strike. Job insecurity and wages were the main causes of the strikes and militant actions from the strikers forced the government to use military force when the police failed to maintain law and order. -

Report to the Survival Service Commission, IUCN and The

Elephant Volume 1 | Issue 4 Article 15 12-15-1980 Report to the Survival Service Commission, IUCN and the Endangered Wildlife Trust: Kaokoland, South West Africa / Namibia Clive Walker Endangered Wildlife Trust of South Africa Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/elephant Recommended Citation Walker, C. (1980). Report to the Survival Service Commission, IUCN and the Endangered Wildlife Trust: Kaokoland, South West Africa / Namibia. Elephant, 1(4), 161-163. Doi: 10.22237/elephant/1521731752 This Brief Notes / Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Elephant by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Fall 1980 WALKER - EWT: KAOKOLAND 161 REPORT TO THE SURVIVAL SERVICE COMMISSION, IUCN AND THE ENDANGERED WILDLIFE TRUST: KAOKOLAND, SOUTH WEST AFRICA / NAMIBIA* by Clive Walker It is with the utmost urgency that I draw your attention to my recent visit to Kaokoland with Professor F.C. Eloff's expedition during September 1978, with the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Kaokoland is in the northwestern part of South West Africa/Namibia and covers an area of some 5½ million hectares (22,000 square miles) and at present is under the control of the South African Government and falls under the Minister of Plural Relations, Dr. C. Mulder. The most striking topographic feature of the region is the many mountains, from the dolomite hills in the south to the stark ridges and isolated eminences rising from the highland plains and to the towering peaks of the Northern Baynes and Otjihipa ranges. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia Katherine Caufield Arnold College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Katherine Caufield, "The rT ansformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 251. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/251 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction Although we kept the fire alive, I well remember somebody telling me once, “We have been waiting for the coming of our Lord. But He is not coming. So we will wait forever for the liberation of Namibia.” I told him, “For sure, the Lord will come, and Namibia will be free.” -Pastor Zephania Kameeta, 1989 On June 30, 1971, risking persecution and death, the African leaders of the two largest Lutheran churches in Namibia1 issued a scathing “Open Letter” to the Prime Minister of South Africa, condemning both South Africa’s illegal occupation of Namibia and its implementation of a vicious apartheid system. It was the first time a church in Namibia had come out publicly against the South African government, and after the publication of the “Open Letter,” Anglican and Roman Catholic churches in Namibia reacted with solidarity. -

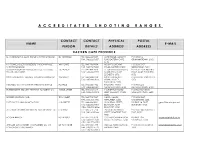

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Imprint Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Publisher: German Museums Association Contributing editors and authors: Working Group on behalf of the Board of the German Museums Association: Wiebke Ahrndt (Chair), Hans-Jörg Czech, Jonathan Fine, Larissa Förster, Michael Geißdorf, Matthias Glaubrecht, Katarina Horst, Melanie Kölling, Silke Reuther, Anja Schaluschke, Carola Thielecke, Hilke Thode-Arora, Anne Wesche, Jürgen Zimmerer External authors: Veit Didczuneit, Christoph Grunenberg Cover page: Two ancestor figures, Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea, about 1900, © Übersee-Museum Bremen, photo: Volker Beinhorn Editing (German Edition): Sabine Lang Editing (English Edition*): TechniText Translations Translation: Translation service of the German Federal Foreign Office Design: blum design und kommunikation GmbH, Hamburg Printing: primeline print berlin GmbH, Berlin Funded by * parts edited: Foreword, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Background Information 4.4, Recommendations 5.2. Category 1 Returning museum objects © German Museums Association, Berlin, July 2018 ISBN 978-3-9819866-0-0 Content 4 Foreword – A preliminary contribution to an essential discussion 6 1. Introduction – An interdisciplinary guide to active engagement with collections from colonial contexts 9 2. Addressees and terminology 9 2.1 For whom are these guidelines intended? 9 2.2 What are historically and culturally sensitive objects? 11 2.3 What is the temporal and geographic scope of these guidelines? 11 2.4 What is meant by “colonial contexts”? 16 3. Categories of colonial contexts 16 Category 1: Objects from formal colonial rule contexts 18 Category 2: Objects from colonial contexts outside formal colonial rule 21 Category 3: Objects that reflect colonialism 23 3.1 Conclusion 23 3.2 Prioritisation when examining collections 24 4.