Under Aulhoritarian Rule-Is a Superior and Proven Slralegy.53 to Be Sure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

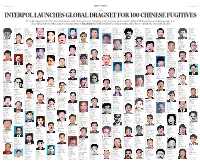

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü Duo 女鐸, 1912–1951

Christian Women and the Making of a Modern Chinese Family: an Exploration of Nü duo 女鐸, 1912–1951 Zhou Yun A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University February 2019 © Copyright by Zhou Yun 2019 All Rights Reserved Except where otherwise acknowledged, this thesis is my own original work. Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Benjamin Penny for his valuable suggestions and constant patience throughout my five years at The Australian National University (ANU). His invitation to study for a Doctorate at Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) not only made this project possible but also kindled my academic pursuit of the history of Christianity. Coming from a research background of contemporary Christian movements among diaspora Chinese, I realise that an appreciation of the present cannot be fully achieved without a thorough study of the past. I was very grateful to be given the opportunity to research the Republican era and in particular the development of Christianity among Chinese women. I wish to thank my two co-advisers—Dr. Wei Shuge and Dr. Zhu Yujie—for their time and guidance. Shuge’s advice has been especially helpful in the development of my thesis. Her honest critiques and insightful suggestions demonstrated how to conduct conscientious scholarship. I would also like to extend my thanks to friends and colleagues who helped me with my research in various ways. Special thanks to Dr. Caroline Stevenson for her great proof reading skills and Dr. Paul Farrelly for his time in checking the revised parts of my thesis. -

Article on the Un Convention Against Transnational

ARTICLE ON THE UN CONVENTION AGAINST TRANSNATIONAL ORGANIZED CRIME AND CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION IN CHINA: DOMESTIC EFFORTS AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION Shang Haowen Huang Gui Table of Contents I.INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 85 II.THE UNTOC AND THE UNCAC IN CHINA: FROM ACCEPTANCE TO IMPLEMENTATION ................................................................................. 90 A. Challenges in Bolstering Anticorruption Cooperation ................. 90 B. Overriding Principles of Combating Corruption .......................... 95 1. Good Governance ................................................................... 95 2. Rule of Law ........................................................................... 102 III.DOMESTIC ANTI-CORRUPTION LEGAL FRAMEWORK .............................. 106 A. Overview of Updates in Chinese Anticorruption Legal Framework ..................................................................................................... 107 B. To Promise and Propose Giving a Bribe Was First Stipulated in the Criminal Law ........................................................................ 109 C. The Corruption Involving Foreign and International Officials Could Be Cracked down on by Criminal Law ........................... 111 D. The Corruption Involving Legal Person and its Liabilities ........ 112 IV.INTERNATIONAL ANTICORRUPTION COOPERATION PRACTICE ............... 115 A. The Domestic Legal Basis of International Anticorruption -

A Sporting Ambition P.26

world: S. AFRICAN PRESIDENT INTERVIEW P.18 | NATION: A SPORTING AMBITION P.26 VOL.57 NO.50 DECEMBER 11, 2014 WWW.BJREVIEW.COM TARGET IN FOCUS China aims to intensify anti-corruption efforts through international cooperation RMB6.00 USD1.70 AUD3.00 GBP1.20 CAD2.60 CHF2.60 JPY188 邮发代号2-922·国内统一刊号:CN11-1576/G2 VOL.57 NO.50 DECEMBER 11, 2014 CONTENTS 38 Ecologically Invested EDITOR’S DESK A conversation with China’s top 02 No Place to Hide eco-business innovator THIS WEEK 40 Market Watch CULTURE COVER STORY 44 The Sound of Hunan An operatic revival takes place WORLD 22 The Korean Quandary FORUM Pyongyang-Moscow meeting under 46 Statesman to Statesman the microscope Veteran German politician offers COVER STORY appraisal of Xi’s new book NATION 14 26 Not a Spectator Sport Coming Together Against Corruption EXPAT’S EYE Giving promising sector a sporting China sniffs out graft suspects abroad 48 Right on Track chance In defense of China’s transportation system BUSINESS 34 Calling Private Investors WORLD Will relaxed policy open investment floodgates? P.20 | Necessary Negotiations 36 Green Desert Seeking a solution to Iran nuclear issue From arid wasteland to fertile wonderland BUSINESS P.32 | Safeguarding Deposits Protecting interests of China’s banking customers WORLD P.18 | A Multifaceted Friendship South African president on collaboration ©2014 Beijing Review, all rights reserved. with China www.bjreview.com Follow us on BREAKING NEWS » SCAN ME » Using a QR code reader Beijing Review (ISSN 1000-9140) is published weekly for US$64.00 per year by Cypress Books, 360 Swift Avenue, Suite 48, South San Francisco, CA 94080, Periodical Postage Paid at South San Francisco, CA 94080. -

Tianbo Li O Inglês Como Língua Global Na China English As a Global Language in China

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Institucional da Universidade de Aveiro Universidade de AveiroDepartamento de Línguas e Culturas 2005 Tianbo Li O Inglês como Língua Global na China English as a Global Language in China Universidade de AveiroDepartamento de Línguas e Culturas 2005 Tianbo Li O Inglês como Língua Global na China English as a Global Language in China dissertação apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Estudos Ingleses, realizada sob a orientação científica do Dr. Gillian Moreira, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Línguas e Culturas da Universidade de Aveiro o júri presidente Prof.Doutor Anthony David Barker, Professor Associado da Universidade de Aveiro. Profa. Doutora Francesca Clare Rayner, Professora Auxiliar do Instituto de Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade do Minho. Profa.Doutora Gillian Grace Owen Moreira, Professora Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro. (Orientadora) agradecimentos My gratitude and esteem go to Professor Gillian Owen Grace Moreira, my supervisor in this work, without her patient direction and suggestions and corrections, this work would not have been presented here. Very special thanks to my family, who have been supporting and encouraging me. To Professor Susan Howcroft and Professor Teresa Roberto, who have constantly encouraged me to keep on my research. To the University of Aveiro, Portugal; Suihua Teachers College and No.7 Middle School of Suihua in Heilongjiang Province, P.R.China; China Mining Industry University; Nanjing University and No.50 Middle School of Nanjing in Jiangsu Province (PRC); which provided valid and valuable information for my dissertation. -

PIERS 2016 Shanghai

PIERS 2016 Shanghai Progress In Electromagnetics Research Symposium Program August 8–11, 2016 Shanghai, CHINA www.emacademy.org www.piers.org For more information on PIERS, please visit us online at www.emacademy.org or www.piers.org. PIERS 2016 Shanghai Program CONTENTS TECHNICALPROGRAMSUMMARY . ......... 4 THEELECTROMAGNETICSACADEMY. ........... 11 JOURNAL: PROGRESS IN ELECTROMAGNETICS RESEARCH . ......... 11 PIERS2016SHANGHAIORGANIZATION . ........... 12 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI SESSION ORGANIZERS . ......... 15 SYMPOSIUMVENUE ........................................ ........ 16 REGISTRATION ......................................... .......... 16 SPECIALEVENTS ....................................... ........... 16 PIERSONLINE ......................................... ........... 16 GUIDELINEFORPRESENTERS............................... ........... 17 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI ORGANIZERS AND SPONSORS . ........ 18 PIERS2016SHANGHAIEXHIBITORS. ............. 18 MAPOFCONFERENCESITE ................................... ........ 19 GENERALINFORMATION ................................... .......... 22 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI TECHNICAL PROGRAM . ............ 24 PIERS 2016 SHANGHAI SESSION OVERVIEW . ..........175 3 Progress In Electromagnetics Research Symposium TECHNICAL PROGRAM SUMMARY Monday AM, August 8, 2016 1A1 FocusSession.SC2: Transformation Optics 1 .................................................................. 24 1A2 FocusSession.SC2: Plasmonic Nanolasers and Active Metamaterials ....................................... 24 1A3 SC2: Thermal and Acoustic -

Full Text of Statement

SaveSandy www.SaveSandy.org Message to American Business in China: No One is Safe By Jeff Gillis March 1, 2017 Chairman Rubio, Co-Chairman Smith, and Commissioners of the CECC, Thank you for this opportunity to testify at this hearing, and for the chance to tell Sandy’s story. Fifteen years ago, there was great optimism by many as China was admitted into the WTO. The belief was that if Western Governments engaged China in trade, China would learn from the West, not just about business, but also about rule of law, property rights, human rights, and human dignity. My wife, Sandy Phan-Gillis, was a strong believer in engagement with China, and a firm supporter of China’s entry into the WTO. She has spent her entire career promoting trade and positive relations with China. Unfortunately, in terms of human rights, admitting China to the WTO has turned out to be a very bad deal. Many of China’s promises have been broken, especially in the areas of human rights and rule of law. That has been clearly shown in my wife’s detention in China by China State Security. The timing of this hearing is important. March of 2017 marks two years that my wife, Sandy Phan-Gillis, has spent in detention in China. Sandy is an American citizen, a wife, a mother, and a resident of Houston, TX for almost 40 years. She was detained by China State Security on March 19, 2015 while on a trade mission to China with Houston Mayor Pro Tem Ed Gonzalez, to promote business between Houston and China. -

Reforming Mutual Legal Assistance

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\86-3\GWN305.txt unknown Seq: 1 20-JUL-18 10:23 NOTE Increasing United States–China Cooperation on Anti-Corruption: Reforming Mutual Legal Assistance Eleanor Ross* ABSTRACT In 2012, President Xi Jinping announced a new anti-corruption policy for the People’s Republic of China (“China”). This policy included sending Chi- nese officials to recover economic fugitives who fled to foreign countries that did not have extradition treaties with China. One such country is the United States, which has frequently refused to provide assistance to China on criminal matters. Sending these officials violates the United States’ sovereignty and ig- nores the legitimate concerns the United States has about the Chinese legal system. The United States and China should enter into a new, bilateral treaty for the provision of mutual legal assistance in criminal matters. This treaty should specifically cover economic crimes, provide for sharing the illicit gains of the economic crimes, and limit exceptions to the provision of mutual legal assistance. This new treaty will allow the countries to create a comprehensive and consistent practice for mutual legal assistance for economic crimes, thus allowing prosecution of economic fugitives attempting to escape justice while protecting the national interests of both countries. * J.D., expected 2018, The George Washington University Law School. May 2018 Vol. 86 No. 3 839 \\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\86-3\GWN305.txt unknown Seq: 2 20-JUL-18 10:23 840 THE GEORGE WASHINGTON LAW REVIEW [Vol. 86:839 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 840 R I. CHINESE EFFORTS TO COMBAT CORRUPTION AND THE U.S. -

International Cooperation Leaves No Place for Corrupt Fugitive Officials to Hide

International cooperation leaves no place for corrupt fugitive officials to hide One of China's most wanted graft fugitives Yang Xiuzhu, who had been on the run for 13 years, finally returned to China on Wednesday and turned herself in to authorities. This was hailed as the latest example of the resolute determination and great effort of the Chinese government in its anti-corruption campaign in pursuing fugitives and recovering illicit assets, read a People’s Daily editorial. So far, 37 fugitives have been repatriated since the Chinese government released a “red notice” for the country’s 100 most-wanted fugitives who used to be public servants or were involved in major corruption cases. Four of the five most-wanted fugitives have already been brought to justice. What’s more, “Operation Skynet,” an anti-graft campaign launched by Chinese authorities in a bid to capture corrupt officials who have fled abroad, has captured 2,210 fugitives as of September, 363 of which used to be public servants. Both the 5th and the 6th plenary sessions of the 18th CPC Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) listed the international manhunt as a top priority of their annual agenda, the editorial said, introducing China’s efforts to bring fugitives to justice. “All corruption cases and corrupt officials should be investigated and punished with great perseverance and zero tolerance. There should be no shelter for corrupt officials in the party!” Chinese President Xi Jinping said at the meeting commemorating the 95th anniversary of the founding of the CPC, declaring China’s determination to crack down on corruption. -

2016 BRICS Goa Summit Final Compliance Report 17 October 2016 to 14 August 2017

2016 BRICS Goa Summit Final Compliance Report 17 October 2016 to 14 August 2017 Prepared by: Alissa Wang, Brittaney Warren and the BRICS Research Group at the University of Toronto and Irina Popova, Andey Shelepov and Andrei Sakharov and the Center for International Institutions Research of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, Moscow 29 August 2017 BRICS Research Group Contents Research Team .................................................................................................................................. 3 University of Toronto Research Team ........................................................................................... 3 Country Specialists ................................................................................................................... 3 Compliance Analysts ................................................................................................................ 3 RANEPA Team ........................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction and Summary ............................................................................................................... 5 Methodology and Scoring System ................................................................................................. 5 The Breakdown of Commitments ................................................................................................. 6 Table 1: Distribution of BRICS Commitments across Issue -

S42009131318p1.Ps, Page 1-110 @ Normalize ( S4-13-0785.Indd )

2009 年第 13 期憲報第 4 號特別副刊 S. S. NO. 4 TO GAZETTE NO. 13/2009 D785 2009 年第 18 號特別公告 書刊註冊條例 (第 142 章) 2007 年香港印刷書刊目錄 (由康樂及文化事務署圖書館總館長辛何艷明編訂) 本目錄列出 2007 年第四季內根據上述條例而送交書刊註冊組註冊的出版書刊。 政府物流服務署出版的刊物,除個別條例草案、條例與規例的文本,以及單張、活頁和海 報外,均列入本目錄。 本目錄主體內容載列以下期刊的資料: (1) 首次出版的期刊, (2) 以新名稱首次出版的期刊, (3) 首次出版而原先在香港以外地區印刷的期刊。 本目錄的英文書刊是按照英國出版《英美編目條例》(第二版) 的格式編訂;香港政府部門 出版的刊物則屬例外,該等刊物是根據部門名稱編排。目錄上每個書項都附有標準書目著錄, 該著錄是參照國際標準書目著錄——專論圖書 (ISBD(M)) 而編訂。中文圖書編目方面,則是 參照經修訂的劉國鈞圖書著錄法。 本目錄每個書項右下方在括號內的編號,代表季內書刊送交書刊註冊組註冊的次序;至於 書項左上方的順序編號,則純粹是作排列用途,方便根據每年刊出的作者索引,從目錄搜尋所 需書項。 英文書刊的著錄使用以下簡寫: bibl. bibliography pbk. paperback c copyright port. portrait ca. circa, approximate date, sd. sewed estimated number $ Hong Kong dollars cm centimetres (unless otherwise specified) col. colour S.l. place of publication not comp. compiler known ed. edition, editor s.n. publisher not known et al. and others sp. spiral facsim. facsimile tr. translator ill. illustration, illustrated v. volume p. pages 2009 年第 13 期憲報第 4 號特別副刊 S. S. NO. 4 TO GAZETTE NO. 13/2009 D787 ENGLISH BOOKS AND PERIODICALS 10941 2006 manpower survey report : retail trade = 10936 零售業二零零六年人力調查報告書. — Hong 1000 English productive vocabulary & quiz = Kong : Vocational Training Council. Retail Trade Training Board, [2007]. — 130 p. : 英文基本詞彙1000聽講讀寫合併本. — Hong Kong : Learner Publishing House Limited, charts ; 30 cm. c2007. — 48 p. ; 26 cm. Text in Chinese and English Text in Chinese and English Unpriced (pbk.) ISBN 978-962-600-232-2 (pbk.) : $65.00 (2007-12129) (2007-11019) 10942 10937 The 21ST Youth Conference of Caretakers of the Environment International = 2006 Lianzhou International Photo Festival = 國際環境守 護者第廿一屆青年會議 / edited by Tom Sze- 2006第二屆連州國際攝影年展 / edited by Duan Yuting. — Hong Kong : Timezone 8 sam Ho. — Hong Kong : Queen Elizabeth Limited, 2007. — 328 p. : ill. (chiefly col.) ; School Old Students’ Association Education 21 x 24 cm. -

Fiscal, Monetary Policy to Help Keep Economy Stable

Getting some air Overseas camps Containing Ebola for students rise International funds raise hopes Dedicated skateboarders elevate sport, in popularity to halt worsening of epidemic hope for spot at Olympics YOUTH, PAGE 18 CHINACHINA, PAGE 4DAILYWORLD, PAGE 12 WEDNESDAY, July 31, 2019 www.chinadailyhk.com HK $8 Fiscal, monetary policy to help keep economy stable Political Bureau meeting decides to avoid real estate market stimulus “The political bureau meeting is further room for fiscal easing on side structural reform, boost said liquidity should be kept ample, infrastructure investment to stabi domestic consumption, further By XIN ZHIMING and LI XIANG on the meeting of the Political Bureau Analysts said the meeting sig meaning the banks’ reserve lize growth in the coming two open up the economy and stabilize of the Communist Party of China Cen naled an important policy direction requirement ratio (cash required as quarters. foreign trade and employment. China will not change its real tral Committee. Xi Jinping, general by showing that the government is reserves) and the interest rate may “As prevailing uncertainty around On Monday, Xi said that “while estate policies to provide shortterm secretary of the CPC Central Commit shunning stimulation through be cut in the second half,” said trade will still weigh on private sec difficulties and challenges in eco stimulus to the economy, but tee, presided over the meeting. boosting the property market, Liang Haiming, dean of Hainan tor confidence, we continue to nomic operations should be noticed, instead will make fiscal policy more “Proactive fiscal policy and pru which is the right way to deal with University Belt and Road Research expect policy efforts to boost direct the economy’s longterm improving effective and “keep liquidity reason dent monetary policy should be well economic weakening.